]

by rahnuma ahmed

`You should not have written about such sensitive issues in such indecorous language,’ faculty members at Jahangirnagar University (JU) told me and my ex-colleague, Manosh Chowdhury. It was 1997, four years before I left JU to become a writer.

We had written about the Provost of a Women’s Hall of Residence. He would target first year women Anthropology students. They handed in a memorandum to the University authorities detailing his abuse of power: he was rude to their family members when they dropped in for visits, he ridiculed what they were taught, and the teachers who taught them (this included us). What was not mentioned in the memorandum however, was that he would often barge into their dormitories. Sometimes, also into the wash rooms. The Provost’s misconduct later made it to the newspapers but what got left out was that he had dubbed three women students ‘lesbians,’ and another, ‘a cigarette smoker.’ We had included these in our article to map out the institutionalised nature of the Provost’s power, to draw attention to the systemic character of sexual harassment on campuses. We had written, The issue is not whether these women are `lesbians’. Women have been scorned on other occassions because they have ‘boyfriends’. Women returning to the halls in the evening are taunted, they are told they were `having fun in the bushes.’ Institutional sexual harassment is not about hard facts alone, it takes place through language, through words that ridicule and scorn. (`Oshustho Pradhokkho na ki Pratishthanik Khomota,’ Bhorer Kagoj, 9 July 1997).

We received no printed response, but hate mail instead. And a genteel comment on our `indecorous’ use of language. Our next piece was entitled, ‘What then does one call Sexual Harassment — A Rose?’ (Bhorer Kagoj, 24 August 1997).

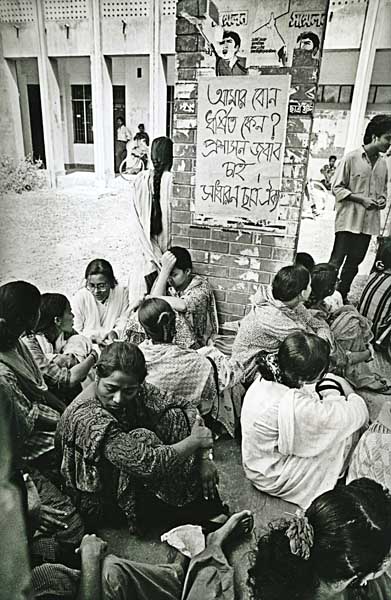

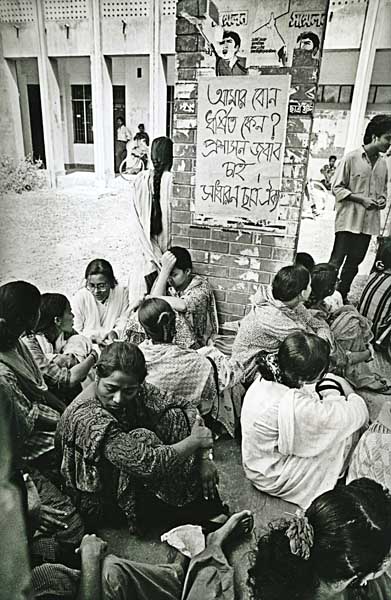

The next year witnessed a student movement on Jahangirnagar campus, at forty plus days, the longest anti-rape campaign in South Asia. The University authorities gave in to student pressure, a Fact Finding Committee was formed. As events unfolded it became clear that a group of male students had been involved in successive incidents of rape which had taken place over several months, and that the University authorities had been reluctant to take action because of their political connections to the regime then in power, the Awami League. The movement was strong and unrelenting and gained tremendous popular support. Later, the university authorities meted out token punishment to those very students whom they had earlier protected, rather reluctantly.

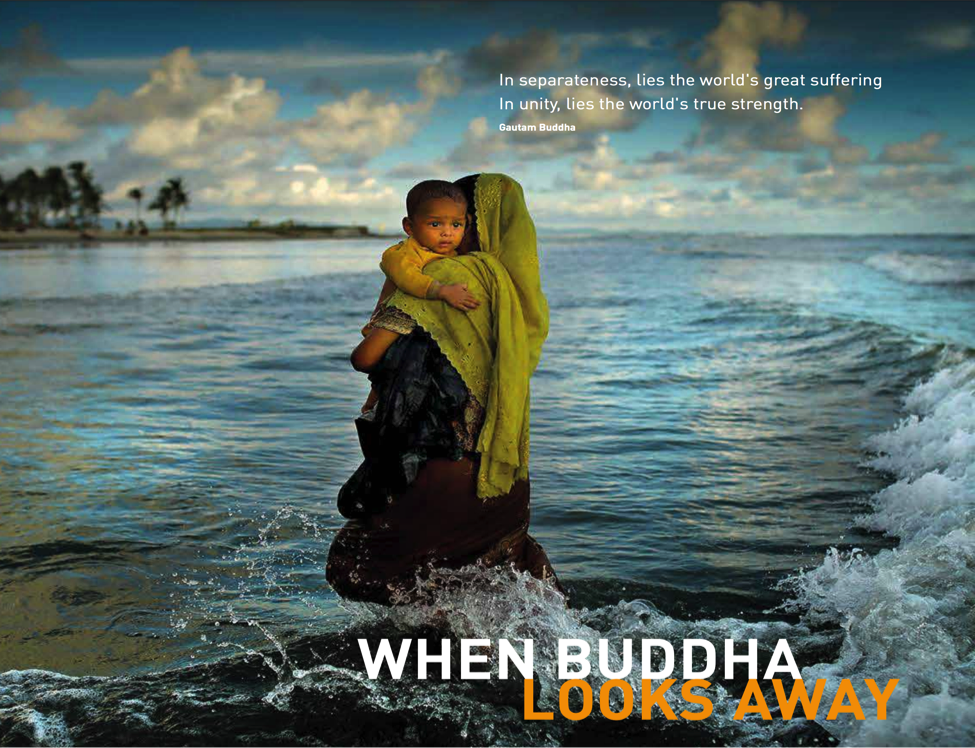

A sit-in protest against rape in campus, brought out by the students union, in Jahangir Nagar University, in Dhaka, Bangladesh. August 24, 1998. ? Abir Abdullah/Drik/Majority World

One of the demands of the 1998 movement had been the formation of a Policy against Sexual Harassment. Dilara Chowdhury, Mirza Taslima Sultana, Sharmind Neelormi and I had worked long hours for weeks on end, to produce a working draft. I remember, our draft had said, sexual harassment is any unwelcome physical contact and advance, declaration of love accompanied by threat and intimidation if not reciprocated, sexually coloured remarks, display of pornography, any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct of a sexual nature…

Policy Against Sexual Harassment: A Torturous Journey

Ten years later.

It’s Friday night, well after ten, Anu Muhammod has just returned from Munshiganj, and I am fortunate to get hold of him. `So Anu, I hear that the Policy has not yet been ratified by the University Syndicate?’ I ask the professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University, a well-known public intellectual and activist, and a good friend of many years. With a twinkle in his eyes and a deprecating smile, Anu launches into the story.

Naseem Akhter Hossain and I forwarded the Draft Policy to the university administration in 1999. Naseem, as you well know was the Provost of a women?s hall, and one of the most dedicated members of the Fact Finding Committee. The university administration was absolutely terrified of the anti-rape movement. For them it was finally over, some of the students had been punished, they wanted to forget the matter. The next year, 17 of us forwarded it to JU administration, with a signed letter. And in those days, the 8th of March Committee was alive, teachers and students would sit and discuss women’s issues and male power, we would hold a rally on International Women’s Day, left groups, cultural groups would join in. It was an annual ritual, each year we would send the draft to the University administration requesting that they take steps to ratify it, to enforce it, each year they would tell us that it had been misplaced. This went on for several years.

Two years later the BNP led alliance came to power, and the elected Vice-Chancellor was removed from his position. Jahangirnagar University Teachers Association (JUTA) protested against the government action. Anyway, to cut a long story short, JUTA initiated a movement in protest against the government’s high-handedness, a common platform was formed, I was present at one of the Teachers Association meetings and took the opportunity to place the Draft policy. Everyone was charged, and the Draft was approved, so you now had JUTA forwarding it to the University administration for ratification. I inquired again the next year but by then we were back to the old ritual, it had been misplaced. But soon, there was another incident of sexual harassment, a BBA teacher, the accusations were proven to be true, he lost his job. We raised the Policy issue again, each movement helped to revive it. I spoke to Professor Mustahidur Rahman, who was then the Vice-Chancellor.

`Yes Anu, what did he say?’ I am very curious about the reasons forwarded on behalf of institutions, by people in positions of power, the language in which they resist measures aimed at ensuring justice. ‘What did Mustahid bhai say?’

Anu’s smile deepened. ‘He said, yes, of course, we must look into it. But we have so much on our hands. I spoke to other teachers as well, why do we need a special Policy, they said. The country has criminal laws, University rules stipulate that teachers must not violate moral norms, we also have a Proctorial policy. So why do we need a separate Policy against Sexual Harassment? In 2007, another movement began, against a teacher in Bangla department. He also lost his job later, and talk of the Policy was revived again. Actually, the women students went on a fast unto death programme, this was very serious, later Sultana Kamal, Rokeya Kabir, Khushi Kabeer, these women’s movement leaders came and pleaded with the students to break their fast. They did, but on the condition that I would personally take up the matter with the University administration. They said, we trust you, we don’t trust the administration.

After this, the University set up a Committee to review the Policy. I was on that Committee, so was Sultana Kamal. Legal points were added, the draft was brushed up, student organisations were invited to comment on it, also, the Teachers Association. But the teachers are not happy, many think that false allegations will be made, that it will be used by those who have influence, on grounds of personal enmity. I tell them that the Policy has clauses to prevent this from happening, any one who brings false allegations will be severely punished, no law of the land, against murder, kidnapping, theft, whatever has such built-in-clauses. Surely, that will be a deterrent? But it falls on deaf ears. The draft was sent to the Syndicate, it was not ratified. The members felt that it required more consideration.

And now, the latest incident, the one involving a teacher of the Dramatics department. I believe the Fact Finding Committee has submitted its report, there is yet again talk of instituting the Policy, but this time it’s serious. There is new VC now, but this time I think they can no longer avoid it. There is strong support for the Policy.

This is how things stand at present. I think the Policy, once ratified, will create history. It will set a strong precedent for similar policies at other places of work. In garments factories, I often say, for women, it’s not only a question of wages but being able to work in a safe and secure place, free of harassment and sexual advances.

`And what about other public universities,’ I ask, knowing fully well the answer. No, says Anu, there is no talk of a Policy, let alone a finalised Draft.

Jahangirnagar has a strong tradition of protest and resistance, our conversation ends on this note. I forget who said it. Was it Anu? Or, was it me? Maybe, both of us?

Voices of Female Students

Four women students of Drama and Dramatics department have accused the departmental chairperson, M Sanowar Hossain (Ahmed Sani), of harassing them.

One of them confided to her classmates, Sir has asked me to go and see him. Well, why don’t you? I am afraid. Why? Another woman said, he has asked me to go and see him too. You too? I don’t want to. Why not?

They talked and discovered that they were not alone in their experiences of sexual harassment, that it was shared. One of them said, as is the practice in the department, I had bent to touch his feet to seek his blessings, as I rose up he pulled me and kissed me on my forehead. Another woman student, similarly abused but silent until the four junior women stepped forward, spoke of how he had grabbed her and kissed her cheek. Another woman said, I was so scared when he said I would have to go to his office, but I was angry too, I knew what was going to happen, I told a friend, I’ll carry a brick in my bag. I want to mark him, so that people kow.

But the women also spoke of how they themselves felt marked. When I went back to the hostel and told the girls they wanted to know, what did he do to you? where did he touch you? how long did he hold you? I wept inside, she said. Why didn’t anyone say, where’s that bastard? Let’s go and get him. Such responses make it so difficult to come out. Why should I take on this social pressure?

The girls also said, if it had just happened to me, if I hadn’t discovered that there were other victims, I would never have spoken out. I don’t think anyone would have believed me.

Male Academia and Its Insecurities

Why do University authorities resist the adoption of a policy that will help institute measures to redress wrongs? That will afford women protection against unwanted sexual advances, thereby creating an environment that is in synchrony with what it claims to be, an institution of greater learning and advancement.

I think what lies hidden beneath academic hyperbole is, although the university, as other public and private institutions, appears to be asexual, in reality, it is deeply embedded with sexual categories and preferences. Men are superior, both intellectually and morally, this is assumed to be the incontrovertible truth. For women, to be unmasking and challenging male practices, aided by a Complaint Cell, members of which will listen to their grievances, extend support, advocate sanctions if allegations are proven to be true, is a threat that terrifies the masculine academic regime of power and privileges.

But sexual harassment is not a bunch of roses. It is serious, it needs to be taken seriously.

———————————-

An open letter to the Chancellor of Jahangirnagar University

First published in New Age on 7th July 2008