rahnuma ahmed

I have not acquired any fortune but I have my paternal estate and the pension of a Subedar. This is enough for me. The people in my village seem to respect me, and are now fully satisfied with the ease and benefits they enjoy under British rule.

Thus wrote Sita Ram in From Sepoy to Subedar, first published in 1873, sixteen years after the first war of independence (the British still refer to it as the Indian Rebellion, or the Indian Mutiny).

Sita Ram wrote the manuscript at the bidding of his commanding officer Lieutenant-Colonel Norgate in 1861, his son passed it on to the Englishman; the manuscript is supposed to have been written in Awadhi, Norgate translated it into English. An Urdu translation is also heard to have surfaced the same year. Few copies are known to have been sold, until 1911 that is, when a Colonel Phillott created a new syllabus for Hindustani exams, taken by colonial officers to test their knowledge of the language. Phillott himself translated the book into Urdu, and from then onwards, the autobiography of Sita Ram, who worked in the Bengal Native Army of the East India Company for forty-eight years (1812 to 1860)—became a ‘key text’ for British officers. The book was still part of the curriculum in the 1940s, it was translated into Devanagari in the same decade; a new and illustrated edition of the book (Norgate’s English translation), was brought out by James Lunt, as late as 1970.

Serious doubts have recently been cast on its authenticity. Was it really written by Sita Ram, or was it authored by Lieutenant-Colonel Norgate himself? Was there ever a Sita Ram, a real-life, flesh-and-blood person? Or, was ‘Sita Ram’ manufactured by Norgate to make the text look, feel, sound authentic?

Is From Sepoy to Subedar genuine, or is it ‘British Empire propaganda’?

What is propaganda?

Simplistically viewed, propaganda is perceived to be ‘all lies.’ But professor Jane DeRose Evans cautions us. The concept, she says, is ‘far more subtle.’

Some scholars view propaganda as a modern phenomenon, a perception which cannot be brushed aside easily since the study of propaganda gained prominence in the twentieth century. Rumors had proliferated on both sides about the horrors inflicted by the other during the First World War, and the ‘widespread employment of methods to alter public opinion’ aroused both interest and fear in the power of propaganda to manipulate the public (David R. Willcox).

But historians remind us that propaganda is not ‘new and modern,’ that the ‘battle for men’s minds is as old as human history’ (Ralph D. Casey). For instance, in ancient Greece, both propaganda and counter-propaganda were part of Athenian life—attempts to mould and shape attitudes and opinions were conducted through the games, the theater, the assembly, the law courts, religious festivals, handwritten books, inscriptions, architecture, and art.

The construction and dissemination of political propaganda caught on in early Rome, a bit later. Evans suggests that it may have been inspired by contacts with the Greek colonies. Toward the turn of the third century BC, Romans began to emphasise the story of how their city was founded; soon after, a few families are seen to ‘boast of descent from various legendary heroes,’ paintings of triumphal processions are made and publicly displayed, precious-metal coins featuring ‘state propaganda’ start being minted. Gradually, ‘individual, familial and state interests’ begin to be intertwined, as is evident in the Esquiline Tomb paintings, in portrait statues honoring ambassadors, in the increasing personalisation of coinage, and the dramatic increase in the ‘number of families claiming descent from mythological heroes or gods.’ Around 125 BC, Julius Caesar and one of the elites used a coin type to suggest that their families had descended from a ‘goddess.’ Roman claims of semi-divine origins of their city and their founders may partly have been occasioned by wanting to bring their status on a par with the founders of Greek colonies, and partly, to ‘justify their imperialistic aims.’

Has the ‘efficiency of propaganda’ increased as a result of modernisation and industrialisation of society? Mass society has made modern propaganda possible, insists psychologist Harold Lasswell, and philosopher Jacques Ellul. The broadening of the basis of politics and the emergence of a mass electorate has made ‘influencing a large number of people worthwhile.’ In addition, technological advances (rapid and widespread dissemination of information) has ‘altered the composition of propaganda.’ While current developments such as the contemporary shift to visual media and the Internet has increased ‘effective contact’ between people, it has also aroused profound concerns about the relationship of technology and society in modern times. Ellul believes technology threatens the ‘freedoms of the social order.’

Is propaganda unique to dictatorships or do democratic regimes also utilise propaganda as a tool? Despite Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s pioneering study, now a classic, Manufacturing Consent. The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), which provides forceful evidence of how the US media ‘serve[s], and propagandize[s] on behalf of, the powerful societal interests that control and finance them,’ western media would still have us believe, as Piers Robinson puts it, that western governments ‘engage in truthful ‘public relations,’ ‘strategic communication’ and ‘public diplomacy’ while the Russians [and Chinese, Iranians, Syrians etc.] lie through ‘propaganda.”

Do only regimes, governments, the politically powerful produce, and utilise, propaganda? Is propaganda deliberate, intentional? Are the consumers of propaganda, i.e., the common people, passive? Scholars are divided over these issues, some insist that the ‘propagandist’ need not be a regime, it could be one person, or groups of persons, or organised groups (such as business corporations). Some maintain that propaganda need not necessarily be aimed at ‘maintaining the status quo,’ in other words, marginalised groups too, may resort to propaganda to counter a state of affairs, or to grab power. Some academics agree that propaganda need not necessarily be premeditated or intentional or systematic, circumstances may compel persons/groups to utilise propaganda. Some are quick to point out that not all propagandists, always, want the active support of those for whom it is intended; propagandist actors/forces may well be satisfied with passive participation. In other words, those in power might well be happy if the majority quietly (passively) acquiesce to the status quo.

From Sepoy to Subedar: Tell-tale signs

‘[My suspicions were first roused by the] convenient parallel between what Sita Ram says and what a British officer would want his sepoys to say,’ writes Jacob Stringer.

Stringer’s list of suspicions: Sita Ram had enormous respect for the British Empire, he loved his officers when they treated him kindly, he disliked those who were snooty and disinterested in their soldiers. He was loyal and brave, he castigated those who had mutinied against their masters, who were stooges of the Nawab of Awadh and the emperor of Delhi. He spoke of his sacrifices for the Raj, of his gratitude for the opportunities that the Empire had bestowed on him. He was unhappy over military failures but reticent over military adventures. Stinger concludes, ‘From Sepoy to Subedar…says…exactly the type of things you would tell a British officer in India if you wanted him to feel he had a right to be there but should be careful in his treatment and deployment of native soldiers.’

Lunt’s editorial note emphasises Sita Ram’s hard work and unswerving loyalty to his masters. His opening line says: ‘Sita Ram Pande, the author of these memoirs, was one of the many Indian soldiers who helped the British to conquer India, and thereafter to hold it…’ And a closing line, ‘[the general reader] may learn…something of the Indian sepoys who served the British so faithfully in good times and in bad…’ (emphases added, in both).

But isn’t it possible, Stringer muses, that many natives were grateful, ‘Who am I to deny Sita Ram the right to gratitude for the material advantages he gained from the British army?’ Perhaps Sita Ram, like other natives, the Tatas, for example, had materially benefited from colonialism? Perhaps close contact with officers of the British army had made Sita Ram an unabashed devotee of the sahibs and European soldiers? Perhaps it had helped him adopt the ‘attitudes of his masters’?

While agreeing that this could well be the case, Stringer insists on scientific evidence, ‘Where is the proof that Sita Ram is real, and freely held these views?’ Until and unless that is made available, Stringer insists, ‘scepticism’ should prevail.

Historian Alison Safadi points out a host of discrepancies surrounding the text, its many incarnations, and various linguistic issues which ‘are most problematic and which cast the greatest doubt on the text’s authenticity’: Norgate wrote that his English translation was published in an unnamed, now defunct Indian journal in 1863 (it has never been found); that the translation was favourably reviewed in The Times of 1863, a passage from the review is quoted by Norgate (in the 1873 edition) but the date of the review is not provided, and contemporary searches for the review have proved fruitless; no one has been able to trace the original/Awadhi manuscript (purportedly written by Sita Ram), not even Phillott; nor has anyone laid eyes on Norgate’s 1863 edition; Sita Ram does not refer to the regiments in which he served by their numbers, nor does he name the officers under whom he served (except for a ‘Burumpeel’ who has remained untraceable, like Sita Ram himself); Sita Ram narrates events which could only be true if he had simultaneously served in several regiments; he uses certain words and expressions which are highly unusual for an Awadh Brahmin as they are ‘quintessentially Muslim’, such as, becoming pak (clean), using a tabeez (religious charm), nikah (marriage), tauba, tauba! (alas, alas) – unexplainable unless, says Safadi, the ‘text was written by a British officer who simply sprinkled the text randomly with Hindustani phrases, either unaware or careless of their etymology and cultural appropriateness.’

British ‘orientalist and essentialist’ attitudes peek out from behind the text, Safadi notes,

I have said that the people of India worship power; they also love splendour, and display of wealth. Great impression is made upon the mass by this; much greater than the English seem to think.

We do not understand divided power; absolute power is what we worship.

[T]hey [the sepoys] liked the sahib who always treated them as if they were his own children.

Does it really matter who wrote From Sepoy to Subedar? It does, argues Safadi, since the text is thought to be genuine, and used as a reliable source of historical evidence by scores of scholars, researchers, journalists and writers (including the celebrated author William Dalrymple).

And of course, the significance of the text cannot be understated: an Indian soldier (son of a ‘Zamindar’) who is loyal to the British during the ‘Mutiny,’ who is (most conveniently) silent about the ‘Mutiny,’ silent about British reprisals as well, which were horrifyingly brutal to say the least—thousands of Indians were flogged, forced to clean bloodied paving stones only with their tongues, summarily hanged or tied to canons and blown.

Since the historical Sita Ram is unaccounted for, it is not far-fetched or absurd to speculate, who could have written From Sepoy to Subedar? (we might as well accept the fact that we will never learn who actually did), and why did it appear when it did?

I find Stringer’s reflections worth quoting in full:

The book’s later adoption by the military education establishment is even more suggestive if we begin to think of it as a form of auto-propaganda among the officer class. What it seems to imply is that certain officers could not feel sure that new officers in the field would understand the full benevolence of the British Empire in India and so should have it explained to them from the mouth of a Real Indian. This raises the obvious question: if the Raj was so clearly a benevolent force in India, what need to explain that to anyone? Surely it would have been obvious in the gratitude of the natives one met everywhere. But as we have seen, the actual gratitude of the native could not be relied upon (emphasis added).

Is propaganda an outmoded concept?

In the 1970s-80s, propaganda was dismissed as an outmoded concept by some, largely for two reasons: the first was connected to the western assumption (or propaganda?) that propaganda was a localised phenomenon, that it belonged to totalitarian orders, that the dismantling of the Soviet Union, and socialism in Eastern Europe, and the global expansion of free market society meant that propaganda was now a thing of the past. Second, theoretical innovations—the ‘new academic lexicon of persuasion, communication theory’ etc.—had led to the notion that propaganda (as an area of study) had fallen out of fashion.

Dramatic changes to the media landscape had also given rise to the need for new theoretical frameworks: increased access to information technology, user-friendly software, alternatives to mainstream and corporate-owned news sources, social media, user-generated content such as YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, citizen journalism, blogosphere, email, mobile phones, the role of the internet in informing, organising and mobilising protests, demonstrations and movements.

Before the spring of 2003, writes Nicholas Jackson O’Shaughnessy, propaganda as a concept had been ‘relegated beyond the marginal to the irrelevant.’ But 9/11, embedded journalism, fabricated intelligence, the mainstream media’s role in passing it off as the truth, and the invasion of Iraq—brought propaganda, back to centre stage.

Did these changes of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, fundamentally transform the field of propaganda/propaganda studies? ‘[D]espite the need for new accounts and theoretical frameworks…research…of many scholars… evidence that some modalities of propaganda in times of war take fairly predictable forms…,’ write Megan Boler and Selena Nemorin. And one of these is the need for a ‘clear enemy.’

The role of the media in securing (manufacturing) consent is crucial, for, as Harold Lasswell writes, ‘So great are the psychological resistances to war in modern nations that every war must appear to be a war of defense against a menacing, murderous aggressor. There must be no ambiguity about who the public is to hate.’ The success of the American mainstream media in demonising president Saddam Hussain of Iraq is demonstrated by the results of a Washington Post poll in September 2003: almost 70 percent of Americans believed that Saddam Hussein was behind the Twin Tower attacks of September 11, 2001. Ten years later US secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld claimed that the Bush administration had never suggested that Iraq was implicated in the terror attacks.

Occurrences such as these, lead philosopher Jason Stanley to ask, ‘How is it that propaganda can thoroughly convince the majority of the country of something that later appears to have been obviously false at the time?’

Propaganda and dissent

Is dissent related to propaganda? What do empirical studies reveal? How do activists view the relationship?

The American propaganda system—as opposed to that of totalitarian states, where the workings of the propaganda system are obvious: the state bureaucracy exercises monopolistic control over the media, official censorship prevails—is far more discreet. It permits dissent and therein lies its ‘beauty,’ write Herman and Chomsky.

The basic institutions and relationships which structure the US media are ownership and control of the media, its major source of funding (advertising), its news sources (the ‘experts’), the ability to complain about the treatment of news (a disciplining tool or ‘flak’), and America’s ‘national religion’ i.e., anticommunism (America’s property owners are haunted by communism, the ‘ultimate evil’).

But while these underlying sources of power play a ‘key role in fixing basic principles and the dominant ideologies’ they do not produce ‘simple and homogeneous results.’ A certain amount of ‘dissent and inconvenient information’ is allowed but these are kept ‘within bounds and at the margins’ so that they do not ‘interfere unduly’ and disrupt the official agenda.

Herman and Chomsky write, facts which undermine the government’s position never make it to the front pages of newspapers. There are no exceptions to the rule. For instance, the volume of inconvenient facts had expanded during the Vietnam War but despite this, news and commentary which did not conform to the ‘official dogma’ simply did not find its way into the mainstream media. The high level of media conformism is reflected in the words of Leonard Sussman of the Freedom House, ‘U.S. intervention in 1965 enjoyed near total…editorial support.’ And, ‘near-total editorial support’ meant endorsement for the deployment of US combat forces in Vietnam, the regular bombing of North Vietnam, and the bombing of South Vietnam on an unprecedented scale (‘unlimited aerial warfare inside the country at the price of literally pounding the place to bits’). It also meant that no questions were raised about the ‘righteousness of the American cause’ nor was any unease expressed about whether ‘full-scale intervention’ was at all necessary.

Things began to change 1965 onwards, dissent and domestic controversy began to be reported in the mainstream media but the actual views of dissidents and protestors were absent; their tactics were discussed but they were largely presented as being a ‘threat to order.’ Those belonging to the antiwar movement were not considered to be ‘legitimate political actors,’ write Herman and Chomsky, their access to television coverage and the print media was limited. Gradually, elite opinion shifted from wholesale support for US intervention to dubbing it ‘too costly’ (in terms of dollars spent, not Vietnamese lives), and being a ‘tragic mistake.’ Apologists for state policy increasingly pointed to the coverage of inconvenient facts, ‘pessimism’ of the media pundits, and the debates conducted over tactics—as proof that the media was hostile, that the US had ‘lost’ the war because the media was ‘adversarial’!

The U.S. media, the authors conclude, ‘permit—indeed, encourage—spirited debate, criticism, and dissent, as long as these remain faithfully within the system of presuppositions and principles that constitute an elite consensus, a system so powerful as to be internalized largely without awareness.’ To press the point about the internalisation of elite values by editors and journalists, they add, ‘No one instructed the media to focus on Cambodia and ignore East Timor.’

While the culture of dissent has largely been identified with the left and left-leaning circles in the United States, some, like the legendary graphic artist Milton Glaser (co-curated the first Design of Dissent exhibition, 2005), believe that dissent is not a matter of who is left or right, radical or conservative, anti-Soviet or anti-fascistic, or an Israeli on ‘the side of Palestinians.’ Dissent, insists Glaser, is basically ‘a response to power.’ Whether rightwing or leftwing or religious, power ‘always attempts to suppress, to subvert, to marginalize opposition’ (PBS radio interview).

The exhibition (accompanied by the book, The Design of Dissent: Socially and Politically Driven Graphics) spans fifty years of the best graphic work protesting against social and political problems such as the Middle East conflict, war on terrorism, racism, poverty, sexism, corporate greed and environmental crises, which have all contributed to people’s diminished sense of ‘safety, power and representation.’ The images question authority, and its ‘passive acceptance.’

It is the manifestation of dissent that defines democracy, says Glaser; in contemporary USA, the media has become ‘exceedingly passive’ vis-a-vis the government, they are simply ‘not willing to take on the President [George W. Bush, Jr.] or the existing government;’ vigorous questioning and an aggressive journalistic community are needed; voicing opinions are not a privilege but a responsibility, crucial to keeping democratic societies healthy. People are increasingly voice-less, the world over, he says.

When asked about the difference between dissent and propaganda, Glaser replies, they are bound together in an ‘inevitable dialectic relationship.’ He adds,

I think there is a difference, which is to say in dissent the dissenters have, it seems to me, the obligation of referring to a central truth and an idea of fairness and a complaint about power.

In propaganda, you have no such obligation. You don’t have to tell the truth. You certainly are rarely complaining about power. You’re simply expressing ideas that you want to enter into the system in order to persuade people to do something. …you wouldn’t talk about a government dissenting from anything fundamentally, because they are the power.

What Glaser terms ‘complaining about power’—taking on the president, vigorously and aggressively questioning those who are in the government, expressing ideas, which the powerful do not wish, be raised—is another name for speaking truth to power.

Dissent as a failure of leadership

We are unwilling to think ‘boldly about the often maladaptive, all-too-frequently unproductive and occasionally catastrophic practices’ of people who, ‘by one means or another’ become encharged with being our leaders, writes Stephen P. Banks (editor of the collection, Dissent and the Failure of Leadership, 2008), with a sense of urgency.

While research studies and popular books on effective leadership have proliferated in the last two decades, so has leadership failure, ‘…instances of leaders who have ruined business organizations, led religious institutions to cover up illegal and immoral behaviour, initiated pre-emptive war and failed to prevent wholesale slaughter of civilian populations…have mushroomed to the point where we no longer are shocked by scandals and institutional catastrophes.’

Is part of the problem rooted in semantics, for after all, what do we mean by the word leader, led, leadership? It means many things to many people (this includes scholars of leadership studies who have been unable to arrive at a consensus), says Banks: the top positions, people in top positions; to take initiative and responsibility; a status as controlling faction; to head toward a destination; to represent, speak for, personify; to conduct and guide; to be in the forefront, to stand ahead of everyone else, to control, direct and reorient others toward correct action etc. It is this ambiguity, this absence of ‘refined distinctions of meaning,’ similar to the ambiguity enjoyed by words such as terrorism, freedom, that makes it ‘strategically ambiguous’ i.e., a word which sounds appealing but resists interrogation by academics and scholars. (Somewhat akin to the CIA’s deceptive expression ‘plausible deniability’—the denial of culpability due to the lack of evidence. Or, as researcher and author Douglas Valentine quipped, ‘The CIA doesn’t do anything it can’t deny’).

A common error in contemporary times is to confuse leadership with an individual’s professional or institutional position or status rather than action (‘the actual behaviours that enhance a group, project or program’). Authors are prone to equating leaders with executive, manager, or to borrow George W. Bush’s vocabulary, ‘the decider.’ When we mean position by leadership, followership is pre-ordained, ‘authority is built into the structure of a relationship based on hierarchy,’ the followers have no other option but to obey. The problem with this notion, leadership-as-position, becomes clearer when we bring in the issue of accountability. Banks cites Abu Ghraib prison torture as an instance, although the Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had said before the US Senate Armed Services Committee, ‘these events occurred on my watch as secretary of defense. I am accountable for them. I take full responsibility’—they were but empty words for no official, no one ranking higher than a Staff Sergeant was punished by a jail sentence or fine. The rank of prison commander Brigadier General Janis Karpinski was merely reduced. This, says Banks, is bureaucratic accountability, the sort of thing which is built into any ‘well-run organization.’ A positional leader can ‘deflect charges of failure’ (inadequate training, resistance to leadership, system glitches, sabotage, political intrigue) because the focus is on the title, rather than the ‘doing.’ I quote,

But the person who authentically takes charge, enrolls others to accept her or his vision for change and changes the group’s direction, purpose or ways of doing things irrespective of position authority, the one whose focus is on the doing rather than the being of a title—that is, the person who genuinely takes action and responsibility…

in other words, ‘doing’ leadership (instead of ‘being’ a leader) means being personally responsible, and that includes being personally liable for one’s failures.

Both Adolf Hitler and Mahatma Gandhi were important leaders but a gulf of difference divides the two, many would distinguish the difference between them by calling one a ‘bad’ leader and the other, a ‘good’ leader. Common sense decrees that a bad leader is one who fails, and a good leader is one who succeeds. But, asks Banks, how can we usefully distinguish between leadership which succeeds and leadership which fails? How can we draw the line between leadership that is likely to succeed from leadership that is likely to fail?

The proposition that tyrannical leadership is bound to fail, is assented to by most scholars of leadership in the modern era, it is upheld as being opposed to leadership which produces outcomes that are ‘morally supportable, socially beneficial and life-affirming.’ Tyrants insist on their followers assent, they manage their relationship with their followers through the tools of direct coercion, fear-induction, dissembling and manipulation, creating dependencies etc. Tyrants suppress dissent.

On the other hand,

The heart of democratic process is the impulse to open up a system to challenge from diverse viewpoints and arguments; once challenged, the leader must either defend her vision or negate the challenge. Thus, encouraging dissent is key to avoiding tyranny and fostering democratic process.

Leaders committed to democratic processes must embrace dissent not only to enhance democracy and avoid instituting tyrannical relationships but because it is essential for the ‘very adaptability and sustainability of any institution or ongoing social group.’ Human groups must adapt to changes occurring outside their own group in order to be self-sustaining, it’s as simple as that.

But mere tolerance or acknowledgement of dissent is not enough, insists Banks; it ‘cannot extract the optimal benefits of dissent [essential] to enhance the system.’ Dissenters must enjoy equal political legitimacy, they must have equal standing and trust, equal access to the power to persuade.

One of the core responsibilities of a leader, he emphasises, is to invite and facilitate dissent, to expand the dispersal of power.

‘Advertising conditions us to accept lies’

It’s not an exact quote, but the substance of what Milton Glaser says in the ‘Design of Dissent’ interview I wrote about above.

Americans have been processed through the intersection of television and advertising, he says. Advertising creates a climate of dissatisfaction—about clothes, style, car, everything, ‘if you buy this car, your neighbors will envy you and your social condition will be enhanced,’ ‘if you buy this breakfast food, you’ll have twice the vitality and you’ll lose weight.’ The dissatisfaction can only be resolved through acquisition and owning; for Americans, happiness is linked to acquiring and owning things.

Advertising is based on an amplification or distortion of reality, it makes emotional claims, ones that are not quantifiably true. Sometimes there is a core of reality, but most of the time identical products are differentiated through amplifying certain characteristics symbolically.

What is most interesting, says Glaser, is that despite knowing these are misrepresentations—at times, outright lies—people still buy the product if the advertisement is entertaining enough. It signals a shift, says Glaser, from the idea that ‘truth is valuable’ to the idea that ‘entertainment is more valuable.’

Lying in public, therefore, no longer has any consequences; the word ‘spin’ is a euphemism for lie, everything is spun. A public that has grown up thus, conditioned by advertising, ‘perfectly accepts political misrepresentation.’ He is convinced, says Glaser, that in the 2004 election President Bush was elected instead of John Kerry because the former was more entertaining, ‘You would be more likely to…vote for somebody that you would also go out [for] a beer with…’ Kerry’s lack of ability to entertain, ‘Ah, I don’t wanna sit still for this guy for four years’ lost him the election. These emotions/choices (or conditioned responses?) are a direct consequence of a population that has been ‘brought up and trained through the media of advertising and television.’ Scepticism is generally beneficial, it works as a kind of protection against accepting ‘things at face value’ but in America, the public’s desire to be entertained overrides scepticism.

All oppressive actions and policies of the government are justified through the threat of ‘terror [attacks].’ There is more dissent than is reported, ‘…once you have a media that is not interested in making trouble, it is also not interested in following the line of dissent.’ To do otherwise, requires those in charge to have courage and Glaser says, ‘I don’t think they are very courageous these days.’

‘Shundorbon shundor thak‘: AL govt advertises Rampal

One would have thought that the Awami League government would not need to fund TV commercials in support of its power plant project at Rampal given that the state machinery is at the government’s disposal; an army of sycophants is at its beck and call; a print and electronic media, largely corporate-owned, affably share common business interests with the government, and additionally, given that news reporting, opinion, analysis, FB posts, and other social media, are all kept in line with the infamous Section 57 of the ICT Act.

At least 21 journalists were sued from March-July this year, mostly for news reporting, under section 57. Civil rights activists call the law ‘draconian,’ ‘uncivilised’ and ‘a tool to silence journalists.’ The Awami League’s chief slogan during the 2008 election campaign was ‘Digital Bangladesh’ (the party’s vocabulary for ‘information society’); the electoral promise was that computer-based technology would be instituted to help ensure education, health, reduction of poverty, jobs etc., that the widespread application of digital technology—billed as the party’s 2021 vision —would help build a society which ensures ‘people’s democracy and rights. But as thoughtful members of the public point out, ‘Digital Bangladesh’ is often a cover for digital repression rather than digital enablement.

The ICT Act was legislated during the BNP-Jamaat regime; the Awami League-led government amended it in 2013, and made it far more repressive by doing away with the provisions which require the police to obtain permission from the appropriate authority in order to file a case or to make arrests. While it is an open secret that the law is selectively applied—to silence criticism of the government, top officials, and ruling party leaders under the ruse of ‘defamation’ and ‘tarnishing the image’—the Information minister Hasanul Huq Inu insists that the government is ‘media-friendly’ and dedicated to ensuring the freedom of the press, and freedom of expression and speech, as enshrined in the constitution.

The offence of tarnishing another’s image is non-bailable; if convicted, the person is punishable by 7-14 years imprisonment, and a fine of up to one crore taka (prior to the amendment, the maximum punishment was 10 years).

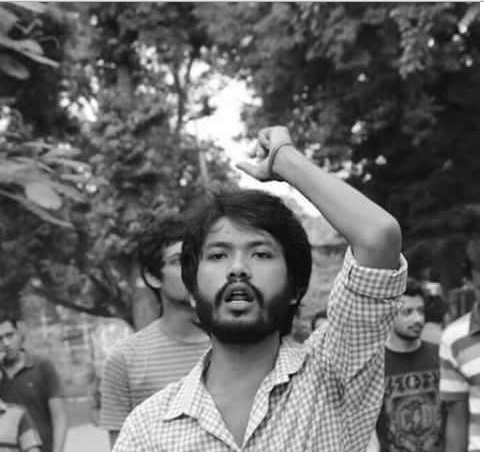

Dilip Ray, left student leader (general secretary, Biplobi Chhatra Maitri), and a final year economics student of Rajshahi University, was arrested by the police from his campus on August 28, 2016. After his arrest, a member of the local Bangladesh Chhatra League, filed a case against him under the ICT Act, for having posted critical comments on Facebook regarding prime minister Sheikh Hasina’s support for Rampal. Dilip’s request for bail was rejected by the Rajshahi Magistrate Court; he was finally granted bail by the High Court after having been in prison for six months.

Biplobi Chhatra Maitri is allied to the National Committee-led Save Sundarbans movement, which insists that coal-fired power plants are bad for the environment but particularly for the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest, sprawling on both sides of the Indo-Bangladesh border. The National Committee to Protect Oil, Gas, Mineral Resources, Power and Ports (NCPOGMRPP, popularly known as the Jatiya, or National Committee) insists that building the Rampal power plant, a 1,320 megawatt imported coal-fired power plant 14 kilometres to the north of the Sundarbans, will destroy the forest and severely affect the livelihoods of 3-4 million forest dwellers and fisherpeople who are dependent on Sundarbans and adjacent water bodies. The Rampal power plant is a joint venture of the Bangladesh Power Development Board and the National Thermal Power Corporation of India (India is the major partner, it is a project that the Narendra Modi government would not have approved on its own soil); Indian people’s movements, green and civil rights organisations and activists are equally fearful of the devastation that the power plant is bound to wreak (‘5 million people living on the Indian side, will be gravely endangered’), and have lent their full support to the Save Sundarbans movement.

Maha Mirza, doctoral candidate and Save Sundarbans activist says, the Rampal project indicates the Awami League government’s ‘one track obsession over high GDP growth as the standard of progress.’ The government’s idea of development is superficial, being ‘merely growth based, consumption driven, and energy obsessed.’ Maha accuses the government of viewing poor people and nature as ‘collateral damage’—damage caused because you happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time for which no one can be held responsible (another failure of leadership).

Actions taken by the government to suppress the nationwide Save Sundarbans movement include brutal police attacks, lathi charge, firing water cannon and tear gas, all on peaceful demonstrations; arrests, harassment, threats, intimidation, slandering, name-calling, and demonisation.

To return to what I wrote earlier, one wouldn’t have thought that the Awami League-led 14-party alliance government would need to fund TV commercials (to ‘alter public opinion’ about Rampal’s impact on the Sundarbans), but as the state minister for power and energy Nasrul Hamid Bipu put it, the National Committee, and the Sundarban Rakkha Committee, have ‘seriously damag[ed] the government’s reputation,’ the ministry can no longer ‘sit idle.’ The government will soon initiate a massive campaign (a ‘publicity blitzkrieg’) to inform the people about the ‘importance of the mega project’ (Independent, September 26, 2016). The news report adds, two leading ad firms, Grey Advertising, and Dhansiri Communication, have been hired to counter the claims of the dissenters, a five crore taka fund has been created for the purpose. It cites Shomi Kaiser, celebrated actress and model, owner of Dhansiri, who said, her ad firm had already made two documentaries.

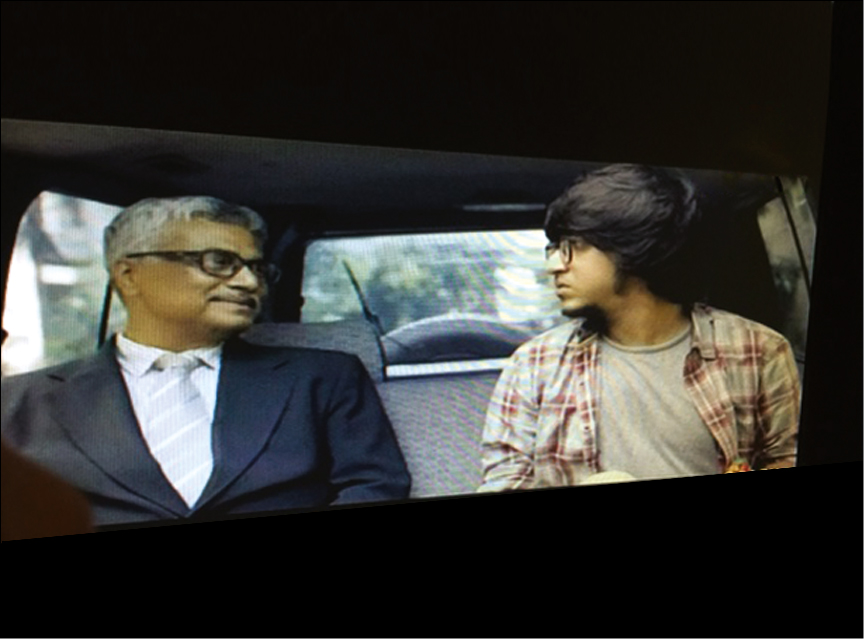

Sundarban will be safe, power project is beneficial, govt loves Bangladesh —dad advises college-going son, opposed to Rampal. (Screen grab from Shundorbon shundor thak, Bangladesh egiye jak).

Dilip Ray, student leader of Rajshahi university, criticised prime minister’s

support for Rampal on Facebook, was jailed for 6 months under Section 57.

If convicted, he could be imprisoned for 7-14 years.

The report states that the TV commercial Shundorbon shundor thak, Bangladesh egiye jak (Let Sundarbans remain beautiful, let Bangladesh progress) has been completed, however, it does not mention which ad firm made it. Since Shomi Kaiser lays claim to documentaries only, I think it is reasonable to assume that the commercial was made by Grey Advertising.

I look up Grey’s website, it brands itself as ‘Famously effective since 1917.’ It claims, ‘whip-smart [and] highly motivated individuals’ work for the ad firm.

But there’s nothing very smart about the commercial. As students of advertising know, you only get a 30-second TV interval to sell your product to a non-captive audience who often wait for commercial breaks to go and get something to eat or make a quick dash to the washroom, or reply to a phone call or talk among themselves. Shundorbon shundor thak is 6 times longer (a whole 3-minute long ad!), half of it is devoted to a lecture, aided by maps and charts and graphics, where a prosperous father expounds on the benefits of the proposed power plant, and Awami League rule, to his college-going son (who is presumably on his way to a Rampal demo), both seated in a swanky car, being driven by the driver. There is more than a hint of bureaucratic creativity (I am reminded of American author Gore Vidal’s words, ‘There is something about a bureaucrat that does not like a poem’) having been a party to its making, a self-satisfied bureaucracy which exclaims, ‘Look how clever I am, I can do powerpoint presentations!’

I watched it several times on YouTube (I will not conduct a detailed analysis of the commercial now, saving it up for later), and thought about the obvious contrast that the makers of the ad draw between the ‘father’ and the ‘son’: the dad is liberal-minded, he presents facts and figures and reasons with his son, while the son is impetuous, superficial, shrill-voiced. The father’s power point presentation-like razzmatazz quickly subdues him, he falls silent. After being dropped off at the college gate, he lingers outside desperately trying to put on a convincing ‘I have left the path of sin, I have received knowledge of what is true’ look on his face, then fumblingly goes inside.

Advertising, Glaser says, is based on a ‘distortion of reality’ and distort this commercial does, for, in real life, a dissenter like Dilip Ray is not reasoned with, or shown graphs and charts and maps, but sued and tossed into jail.

Awami League’s norm: ‘Grateful subjects’?

In propaganda, Glaser had said, ‘You don’t have to tell the truth. You certainly are rarely complaining about power. You’re simply expressing ideas that you want to enter into the system in order to persuade people…’ Of what? To be grateful? To be silent? Servile?

But the costs are high, as Banks reminds us, for leadership that does not produce outcomes which are ‘morally supportable, socially beneficial and life-affirming’ risks threatening the continued existence of the group.

Something Dilip, in his early 20s, understands,

‘Bangladesh is a democratic country and the freedom to express our opinions is a given. If someone is arrested for having differing—albeit rational—opinions, this isn’t a good sign for our country.’

but the aging coterie that rules the country, and its army of professional sycophants (including the whip-smart and highly motivated), fail to.

Published in New Age, November 16, 2017

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.