Shahidul Alam?s new show combats Islamophobia, extremism: The Punch

For celebrated Bangladeshi photographer, writer and curator Shahidul Alam, a just world is a plural space where many thoughts can coexist. His latest show, Embracing the Other, opens in Dhaka on May 8

“If you?re not making certain people uncomfortable by your presence, you are probably doing something wrong.? Bangladesh?s best-known photographer, writer and curator Shahidul Alam, 61, has lived by that adage, which, by and large, sums up why he does what he does.

For Alam, who has been actively involved in the movement for democracy in Bangladesh for over three decades, photojournalism was a corollary of being an activist on the streets, seeking to see himself on the edge, so as to constantly ?feel the heat?, questioning, going beyond the obvious, not settling for safe options.

In Bangladesh, Alam is credited with many ?firsts?: Among other things, he set up Drik Picture Library, the country?s first picture agency, in 1989; Pathshala, its first photo school in 1998; and the first email network in the country in 1994. He also founded the first photo festival in Asia, Chobi Mela, in 2000.

A graduate in Biochemistry and Genetics from Liverpool University and a PhD in Organic Chemistry from Bedford College, London University, Alam started photography in 1980 in London. In 1983, he won the Harvey Harris Trophy from London Arts Council. It was also the year when he started working professionally at ?Young Rascals? studio.

In 1984, Alam returned to Bangladesh, which has been the turf and territory of his creative pursuits. A self-taught artist, he has learnt from his experiments, never shying away from innovation, pushing the envelope, redefining the contours of his art practice every time he works on a series, holds an exhibition or puts together a book.

He has been exhibited in MOMA, Centre Georges Pompidou and Tate Modern and has been to Harvard, Stanford, UCLA, Oxford and Cambridge universities as a speaker. He is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and a recipient of the highest national award given to Bangladeshi artists.

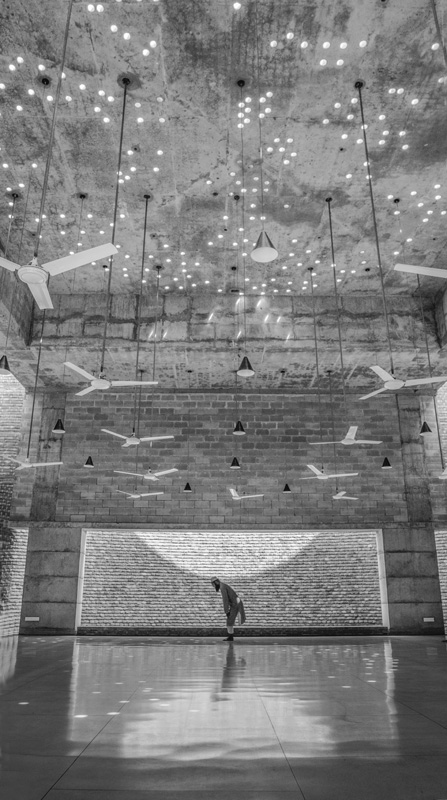

Today, Alam is a veritable institution unto himself. His latest exhibition, ?Embracing the Other: Photographic Exhibition Inside a Mosque?, is a part of the series of ground-breaking works. In the show, he combats both Islamophobia and extremism. The photographic exhibition on the Bait Ur Rouf mosque, designed by Marina Tabassum, winner of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for 2016, will surprisingly take place in the mosque itself. The show, which opens on May 8, will be open from Fajr (dawn) to Isha (night) prayers until May 10. Curated by Rezaur Rahman, it is expected to tour globally.

The first urban element introduced by the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) to the city of Madinah, says Alam, was the mosque, which functioned as a community development centre. He says that the mosque was used as a centre for religious activities, for learning, the seat of the Prophet?s government, a welfare and charity centre, a detention and rehabilitation centre, a place for medical treatment and nursing, and a place for leisure activities. The prophet is known to have permitted women to sleep in the mosque, and for non-Muslims to pray there. ?It is this openness and the ability to reach out to the other that appears to be missing today, in everyday life and in the mosque,? says Alam, talking about the show. Excerpts from an interview:

INA PURI: Earlier this year, when Chobi Mela 2017 opened in Dhaka, as its founder curator, this is what you had to say: ?Whether our art can transcend the class barriers we are plagued by, whether our artists see the person in the street as their audience, whether the work we produce caters merely to the market or contests how the powerful would have us see, will in the final analysis determine whether art is a weapon of resistance or yet another toy for the privileged elite.?

During my visit to Dhaka for Chobi Mela, what struck me was the festival?s most unique location. Addressing global issues ? like border, migration and surveillance ? the festival journeyed deep into the labyrinthine lanes of Old Dhaka to Beauty Boarding House and Bulbul Academy, setting up the exhibitions in these premises with a view to encouraging multiple dialogues. It was absolutely marvellous how the ordinary layperson engaged with the narrative and dialogue became a spontaneous part of the exercise.

Please elaborate on this year?s theme ? Transitions. How did you select the works of 37 photographers from across the world? Give us a sense of how the festival traced the trajectory of memory and the self, personal spaces, and that of communities, through these works.

SHAHIDUL ALAM: The public chose the theme ? albeit an art-loving and privileged public as it required Internet access and the luxury of being able to go to art exhibitions. Within those limits, the choice, therefore, represented common aspirations and general concern. This is not at all surprising. The ?War on Terror? and the imperialist war-mongering that preceded it have stoked huge unrest in the non-Western world, though much smaller violent incidents in the West generally take up most of the global media?s coverage. The average person and people living in the Islamic regions in particular feel far less secure than they have done in recent times. Total disregard for human rights, greed, blatant hypocrisy, and an unabashed promotion of the military industrial complex have led to the crisis we are in. This is reflected in the work presented at Chobi Mela and I am sure would also have lingered in the minds of the curators. The clinical observations within an interrogation chamber; a drone eye view of the US backyard; revisiting the colonial past, are all manifestations of this phenomenon. However, the selection process was by no means automatic. It started with the formation of the selection panel itself. The curatorial team contained photographers, art managers, curators, a non-photography-based fine artist and an architect.

All of them engaged with photography in various ways, but each brought a unique aspect that enriched the mix. Sadly, it was all male, all-Bangali, reminding us that we still have much to do. Of course, one remembers what has been shown in the past ? trends, past and present. But there was a distinct attempt to show work at the edge, and to show it in a manner that swerved the viewer to the precipice. Being comfortable is not what one comes to Chobi Mela for. One is provoked, angered, soothed and questioned, all in one heady mix. Emerging students showed shoulder to shoulder with legendary artists. While the fine art community at large has marginalised photography, our response was not to reciprocate, but rather to reach out and create spaces for practioners from other media. The commissioned work of the fellows, work that was produced especially for the festival, added flavour to this already spicy recipe.

Going out of the white cube to derelict theatres, riverside parks, an old dance studio combined with work that bucked the trend, revelling in these alternate spaces. Beauty Boarding, an old hangout of philosophers, poets and writers, reminiscent of Montparnasse in the 1930s, relived that old charm, with willing guests giving up their rooms to make way for brightly painted walls, perfect for an outlandish show. And, to top it all, the mobile rickshaws that are the trademark of Dhaka, turned what might otherwise have become an elite event, into an art appetiser for the masses. If the audience does not go to the gallery, the gallery must go to the audience. It is rare that fine art of the highest order reaches out to a public that rarely sees itself as a connoisseur of art. These peripheral shows rather drew the public into the more traditional white cube space of Shilpakala Academy, which was unrecognisable because of its transformation. There was an eclectic mix of work, each meticulously presented. Chobi Mela is a great wine to get drunk on.

Azan (top) and Boys (above), which will be part of Alam?s new show, ?Embracing the Other?

INA PURI: Another ongoing project of yours, ?Kalpana?s Warriors?, also explores the idea of expanding boundaries and involving entire communities as part of the artistic dialogue.

SHAHIDUL ALAM: Kalpana Chakma was the Che Guevara of Bangladesh?s hill people, the paharis. It is remarkable that a people who sacrificed so much blood for the right to speak its own language so quickly turned on itself when its own minorities tried to preserve their culture. The nation?s founding father, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had famously said to the paharis ?tora bangali hoiaja? (you become Bangalis), when he himself had so ably resisted when Jinnah had demanded that we become Urdu speakers. Years of brutal military occupation have followed. The torture and killing of Romel Chakma ? a 19-year-old Jumma youth ? by the military, a few days ago, is the most recent reminder of ?peace? being shoved down pahari throats. Kalpana had been the charismatic leader of the hill women. Her defiance, her leadership and her love of her people and of freedom made her a threat to the military.

Extrajudicial killings (?encounters? in India, ?crossfire? in Bangladesh) and enforced disappearances (goom) are familiar to the South Asian citizen. When the state becomes a vigilante, whom does the citizen turn to? It was the spectacular success of my previous work ?Crossfire? which prompted me to address the single biggest taboo in Bangladesh, criticism of the military. Not only had we been able to legally challenge the government, we had the armed police removed from outside Drik, and the show reopened. The massive public support, the rallying of the media, the gumption of the courts, were all indicators that the nation was ready to resist, it merely needed someone to take a stand, and an innovative strategy that could be used to seep through the cracks.

?Kalpana?s Warriors?, the third of a series of ongoing exhibitions shedding light on the story, leads on from the pseudo forensic technique used in 2013 to the intimate view of Kalpana?s personal artefacts in 2014 and on to the currently touring show. The need for alternate vocabularies was clear. Strategically, a non-literal representation made it more difficult for the government to challenge the work, without incriminating itself by admitting culpability At an aesthetic level, ?Crossfire? had already shown how powerful alternative vocabularies could be, with the work being used by users as diverse as Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, by local activists who took it to villages, and also fine art audiences in places like Tate Modern and Kochi-Muziris Biennale. It demonstrated how broad a spectrum such methods could reach.

The intersection of art, science and politics creates spaces of intervention that activists have not exploited sufficiently. Photography?s forte is in demonstrating the visible. Artists who have been in the right place at the right time and have used their sensibility and their visual and narrative skills to make us see what they were witness to, have left behind powerful documents that continue to move, provoke and inspire us. Photographing the invisible is a much more challenging task for photographers, but often that is the space we need to inhabit. At the time we were planning ?Kalpana?s Warriors?, she had been missing for 19 years. Even many of the visible traces of her presence were gone. So we decided to photograph her legacy. The people she had inspired and those who continued to resist because of her. It was these warriors we were going to portray, but we needed to do more than merely take their portraits.

While interviewing the ?warriors? they repeatedly talked of how little furniture there was in her home. Not much more than the straw mats she used to lie upon. It spoke not only of her minimalistic needs , but also highlighted how a woman who had materially so little, could be so powerful and so feared by a state that it felt the need to make her disappear. That prompted the choice to print the photographs on straw mats. Of course, then, one needed to develop the technology to do so. Kalpana?s brother, Kalindi Chakma, who was the last person to see her alive, mentioned that Kalpana, in her previous conversation with her abductor, Major Ferdous, had bitterly protested the burning of pahari homes by the military. So fire became another tool in the cog.

We had started the ?No More? campaign at Drik in 2010 with ?Crossfire?. Since then, we?d been documenting the garment industry and shown work on the Tazreen Fashions and Rana Plaza disasters. The garment factories use a laser devise to scour the jeans that feature designer tears. Using the same laser as the source of the fire needed for the process completed the tool set. Of course, a straw mat, and a laser device do not in themselves create a photographic print. After considerable research and numerous failures, we were able to develop the technique to etch the straw mats using the laser device to create photographic images with the subtle gradations we needed. It also involved using a particular type of lighting. For this, we used the utensils found in pahari kitchens as the gobo! It was a slow process and very prone to error, so we also needed very patient and extremely forgiving models! But it did work and the results were spectacular. We had unexpected outcomes too. We used candles in a darkened gallery to create the right ambience for the work. However, while one could not see in the dark space as one entered the gallery, the smell of dry grass created a pahari presence, creating a connection to Jumma life. Because of the particular nature of the work, it has to be redesigned for each space, giving new life to the work in each reincarnation.

The work continues to travel, and has helped to keep the resistance alive. In a country where speaking against the military is so fraught with danger as in many other places, the showing of Kalpana trilogy (the three bodies of work I have so far produced on Kalpana Chakma) has provided one of the few opportunities where paharis have been able to openly question military action.

INA PURI: At the core of your forthcoming project, ?Embracing the Other?, is the belief that within the climate of hate and intolerance, religious tolerance could be possible.

SHAHIDUL ALAM: The current level of religious intolerance is part of a more general environment of intolerance and more specifically, suppression of dissent. Our non-elected government, not having the people?s mandate, has used the state machinery to keep itself in power. As such, it has on the one hand, quelled opposition of any form, to shield its vulnerability. It has used the bureaucracy, the military and the police, as well as its traditional armed cadre to put down dissent amongst the public, the intelligentsia and even contrary voices within its own party. It is generally known that Indian support has also been a key force in bringing the government to power and in keeping it there. As such the government is beholden to all these forces. Its vulnerability has also meant that it has had to appease Islamist groups.

Instead of protecting the victims of violent attacks, the government has decided to reduce the political space for secular voices. After the Holey Artisan attack, it was no longer possible to ignore this threat, but the government has used this attack as a way to further broaden the powers of the already repressive security forces. On the one hand the government has been making deals with Islamist groups as a pre-election campaign. On the other hand, ordinary citizens, who may well be religious and God-fearing, find themselves being targeted as potential terrorists. The rise and political consolidation of Hindutva in India has also inflamed religious sentiment in Bangladesh, leading to greater polarisation.

The average Bangladeshis are God-fearing, religious and Muslim. They are neither fundamentalist nor inclined towards violence. The lumping of Islam with violence, and the inability of left-leaning and secularist groups to engage with Islam has not only created distance, but also made it difficult to have conversations on common ground. On the other hand, Islam has always been a very pragmatic religion, and deals with almost every facet of one?s life, from sex to business. The first urban element introduced by the Prophet to the city of Madinah was the mosque, which functioned as a community development centre (https://medinanet.org/2016/09/the-form-and-function-of-the-prophets-mosque-during-the-time-of-the-prophet/). It was used as a centre for religious activities, as a learning centre, as the seat of the Prophet?s government, as a welfare and charity centre, as a detention and rehabilitation centre, as a place for medical treatment and nursing, as a place for leisure activities. The Prophet is even known to have made arrangements for women to sleep in the mosque, and for non-Muslims to pray there. It is this openness and the ability to reach out to the other that appears to be missing today, in everyday life and in the mosque itself.

A common perception that photography is haram is ludicrous as photography has only been in existence for less than two centuries. Islam does prohibit idolatry, but that is the very mode of governance in Bangladesh today (and in many other countries). Political posters espousing dynasty politics obscure all other visual cues in the public space. Political leaders are sacrosanct and above question.

Bait Ur Rouf, the mosque in question, is a work of art in itself. The sculptural quality, the use of light, the tranquility of the space, the intelligent use of geometry and the natural ventilation, are some of the features that probably contributed to the Bait Ur Rouf mosque winning the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2016. For me, the fact that a woman had donated the land and that her granddaughter designed and built it, are also exciting aspects. It is a mosque with no minarets. No air-conditioning. No special altar for the imam. The conceptual similarity with Prophet?s mosque where salient features were, function-form relationships (the square and the cylinder); respect for the environment (use of natural light, non-use of air-conditioning); cleanliness (the mosque is spotless, with virtually no furniture); comprehensive excellence (the Aga Khan Award for design); promoting just social interactions (no hierarchical position for the imam), indigenous versus foreign influences (use of local bricks without plaster), increases its authenticity.

The idea of this exhibition is to both remind the religious that Islam endorses a much more inclusive culture than is practised either within or outside mosques, and remind secularists that religion was designed as a force for social cohesion, rather than division. At a personal level, I also want to be able to access the mosque for my art. Can you imagine a thousand mosques in Dhaka city suddenly becoming available to all?

INA PURI: As an activist and photojournalist covering conflict zones for decades, you have witnessed first-hand the ever-increasing chasm between ethnic communities and, sadly, the violence in our world has only worsened in recent times, affecting people and countries. What does the project hope to accomplish? Are you daring to dream that things will improve,someday?

SHAHIDUL ALAM: I am an optimist, but I am a pragmatist too. It is when we are made to believe that we are incapable of bringing about change that those who maintain the status quo have won. It is through such indoctrination that we accept repression, autocracy and injustice. Not only must we believe in change, but we need to be actively engaged in the process of change. To not be doing so consistently is to be aiding and abetting the oppressors. My skills are in photography and writing. That is the space for my intervention. If the mosque is the traditional commons, then that is the space I must occupy.

INA PURI: The mosque has traditionally been a place of prayer and meditation. In the recent past, however, madrasas and mosques were used by the fundamentalists for brutal attacks and hate-mongering. These spaces with no history of past violence metamorphosed gradually into centres for disseminating education on violence. How will ?Embracing the Other? actually heal? How will you build bridges between diverse warring factions? How will you preach peace to the disillusioned youth?

SHAHIDUL ALAM: As I?ve mentioned earlier, the depiction of the mosque as merely a place of prayer and mediation is historically incorrect, as it is historically incorrect to depict the mosques and madrasas as the only sources of fundamentalist thought and violence. In both absolute and relative terms, by far the greatest violence being perpetrated today, particularly on civilian populations, is by the huge militaries of the largest weapons manufacturers in the world. The problem is that they also own most of the international media, leading to their acts being described as benign, while the actions of their opponents are described as ?terrorism?.

The disillusioned youth will need more than preaching. They will need jobs, security, opportunity and hope. None of that is currently available. Unless a radical shift takes place in our social system where the interest of the ruling class is preserved above all else, they will turn to other options. Extremism is just one of them.

In my numerous visits to the mosque, I, of course, saw people praying. I also saw people (invariably men), sleeping, eating, and conversing. I saw children running around. I even found a goat one day, and then a sparrow came in, trying to find a nesting place. As I walked through one afternoon, watching the shadows dance across the bricks, I came across a red cricket ball. It seemed to fit in with the bare brick floor. It was similar in colour and the inner curve of the cylinder complemented its shape. It was not what I was expecting. The following day, during the Friday prayers, another cricket ball, this one, newer and more brightly-coloured, bounced in. I anticipated angry voices. I didn?t think the special prayer of the week being disturbed by playful children would be taken lightly. I was surprised as one of the devotees in the front row caught the ball, smiled, looked around and sent it back through the gap in the wall in the mehrab. This mosque, I sensed, was different. It was a lived space, forgiving, open and receptive, just as the Prophet had intended mosques to be.

If this show succeeds in bringing in people who would normally have never entered a mosque; if it challenges the devout by making them question their method of worship; if it helps the mosque become the inclusive community space all mosques were intended to be, it will be a major step forward for the young and the old, for men and for women, for believers and non-believers alike.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.