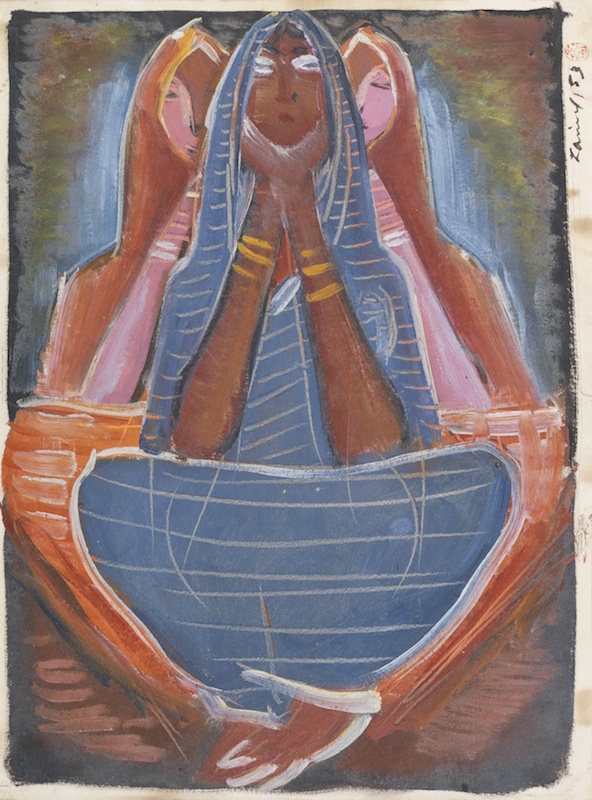

?What gives me even more joy than creating my own artworks is seeing art being nurtured?in?society…Art should be turned into an all-pervasive, daily practice.” Zainul Abedin

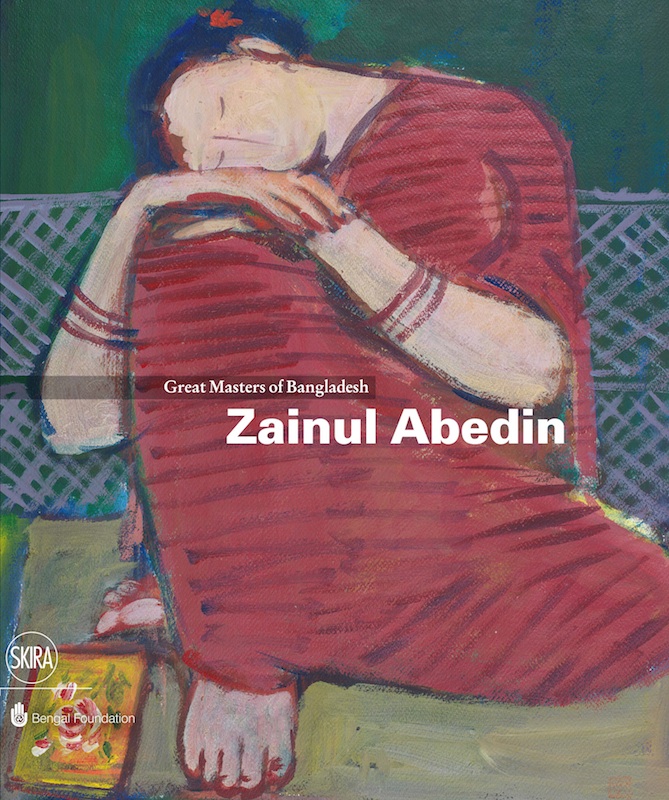

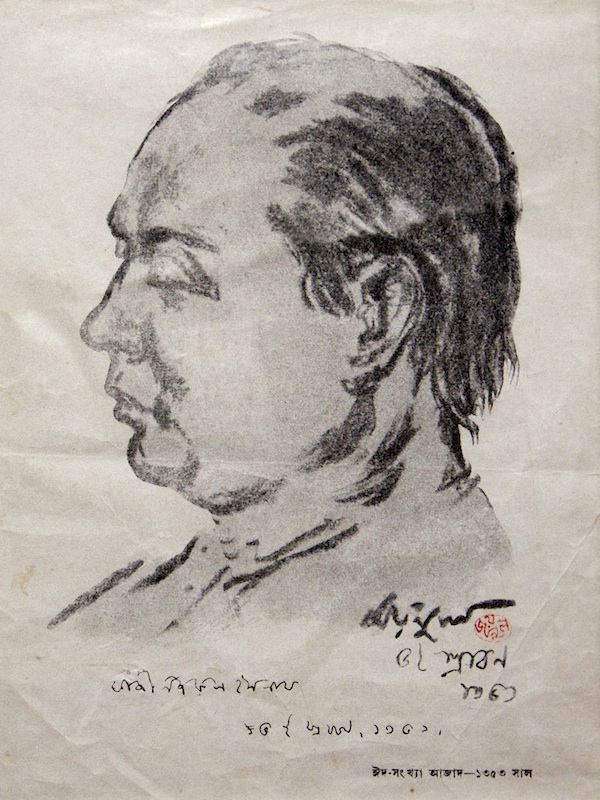

The only comprehensive survey of?Zainul?Abedin?s work to date and the second volume?in?a?world first series dedicated to the ?Great Master Artists of Bangladesh?, edited by Rosa Maria Falvo, co-published by Skira?inMilan and the Bengal Foundation?in?Dhaka.?Zainul?Abedin?(1914-1976), reverently called the?Shilpacharya?or ?guru of art?, is the architect of the modern art movement?in?Bangladesh, which began with the setting up of the first Government Art Institute?in?Dhaka?in?1948. For his devotion to art education and his visionary and artistic achievements?Abedin?has always been the undisputed protagonist of the Bangladeshi modern art scene. With essays by Abul Monsur, Nazrul Islam, and Abul Hasnat, this book showcases?Zainul?Abedin?s work over?aperiod of 40 years, with more than 200 colour and black and white plates illustrating his special relationship with his country, from various artistic, social, and political perspectives. This beautiful and ground-breaking volume retraces his personal vision and provides the best interpretative angles into?a?culture and reality that has often been overlooked and even misunderstood?in?the West.?Abedin?s humanitarian stance and his commitment to art forged the way for an entire generation of Bangladeshi contemporary artists.

http://www.skira.net/zainul-

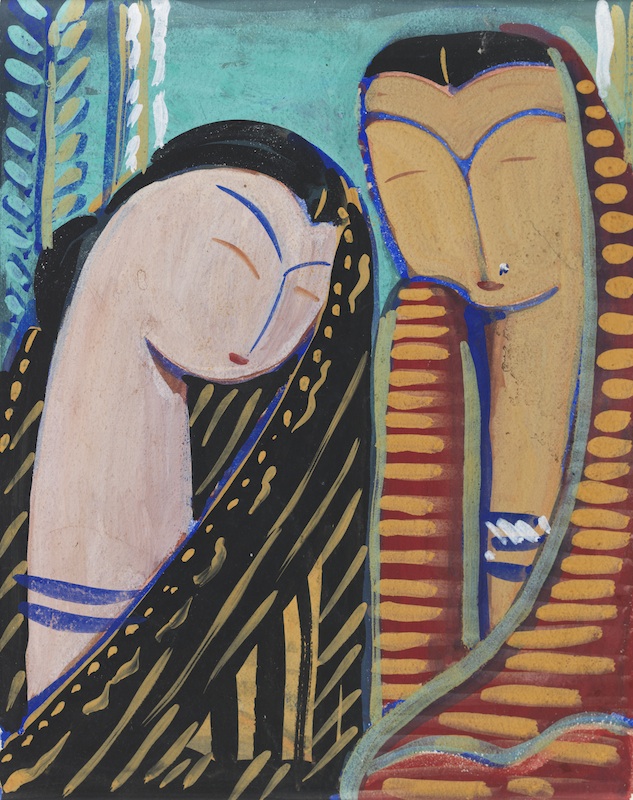

Philosophically, Zainul Abedin was concerned with the plight of the everyman. This extraordinary artist, teacher, and humanitarian wanted art to permeate education and validate the lives of people at all levels. Sidestepping his own career in the service of building opportunities for other artists and generations to come, Abedin clearly lived his personal vision to make a difference in the art world. Gifted by birth and burdened by circumstance, he took on the responsibility of sharing ways of identifying one?s own voice and collocating this within a collective song; revealing new ways of participating in society. Born into a lower-middle-class family, his empathy for those struggling to make a living was evident from the start, and his eventual appointment at the Calcutta Government Art School in 1938 paved his destiny as the ?avatar? of modern art in Bangladesh.

The artist?s intimate communion with the natural world is also clear. Its creative, destructive, and regenerative powers are keenly observed throughout his work. Flying over the Himalayas, I have been fortunate enough to see the breathtaking snow-capped landscape and to discover the immense floodplain stretching between the mountains and the sea. Bengal is like the showerhead of the planet, since almost all water running off the Himalayas must pass through it. Every spring the melting snow and ice sweep the terrain and form rivers that rush into the sea. This ageless process of building up the world?s largest ?Green Delta? has created the shimmering territory we now know as Bangladesh. From the south, numerous rivers run to join the great Ganges, flowing through India before it enters Bangladesh, where it is also known as the Padma, and spilling into the Bay of Bengal. From the north, the majestic Brahmaputra (Yarlung Tsangpo) forms in Tibet, flowing past Lhasa, and twisting through the north-east corner of India to reach northern Bangladesh, where it is also called the Jamuna. The role of water ? river, rain, and sea ? cannot be underestimated in a country as unique as Bangladesh. In winter, Mother Nature seems benign; rivers shrink, skies are blue, and saline water trickles in. In summer, she is wilful and the land becomes amphibious; rivers widen, rains pour down, and sea storms rage. The result is flooding, which means constantly fertile soils with luxuriant vegetation, but also the hostile certainty of severe inundation every few years. [1]

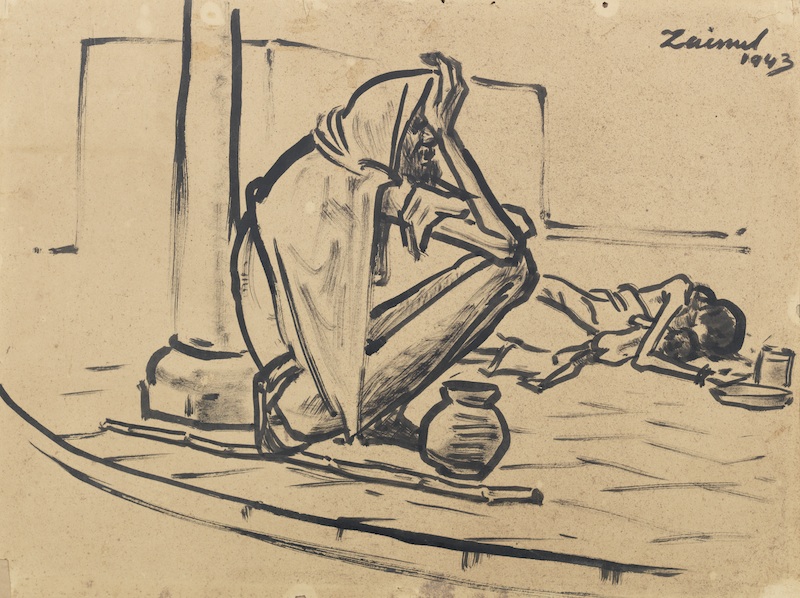

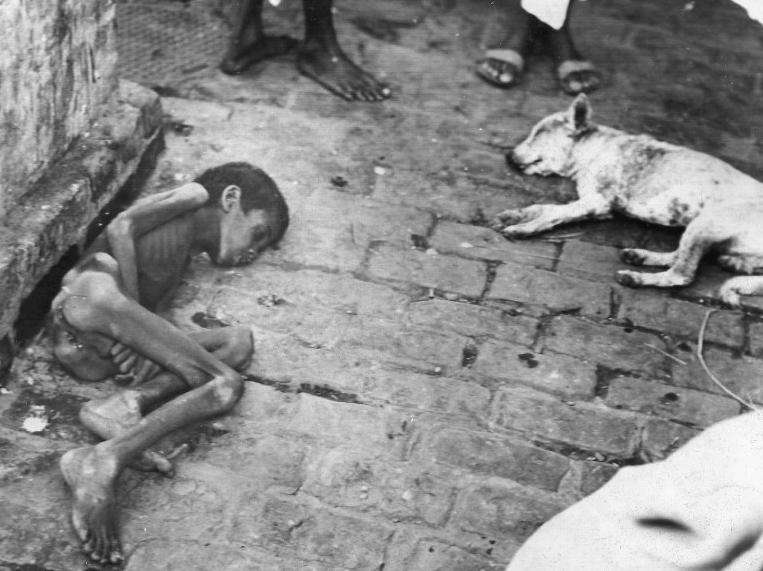

Abedin?s early works on the tranquil rhythms of village life in Mymensingh, where he grew up with the river as his ?greatest teacher?, and his Dumka watercolour series, indicate a romantic interpreter of an idyllic Bengal. Given such tireless natural beauty and favourable conditions, the paradox of famine seems all the more terrible; like a merciless sickle of death harvesting human beings. Indeed, the Bengal Famine of 1943 radically changed the nation and Abedin?s approach to art, propelling him into an uncompromising realism that was to distinguish him throughout the subcontinent. Claiming millions, this famine still makes for uncomfortable discussions. Nobel Laureate and Bengali economist Amartya Sen has argued that starvation was not inevitable: ?The war efforts had expanded the income of a lot of people, particularly in urban areas benefiting from what was effectively a war boom? The central government in Delhi had prevented trade between one state and another? deciding the entire population of Calcutta would be covered by ?ration shops at fair prices?, which really meant they would buy rice from rural areas at whatever price they could get and then subsidised would sell in urban areas. So that of course made food prices shoot up?? [2]

Perhaps lost amid the death tolls of World War II or overshadowed by the partition of India and its subsequent independence, the Bengal Famine was nonetheless a cataclysmic loss of human life. Indian (Bengali) filmmaker Satyajit Ray (1921?1992) produced a moving version of this phenomenon in his 1973 Distant Thunder (Ashani Sanket). Seen through the eyes of young lovers, the film harks back to secular, rural, and creative traditions suffering under the zamindar system and other organisational instruments, such as British mercantilism, religion, and caste. It eulogises ordinary people?s Herculean ability to rise above calamity with dignity and collective resilience. While Ray?s own objections seem intentionally muted, by the end of the film we see a backdrop of victims eloquently tracing the landscape. Few historians dispute this famine was man-made, but there is much less consensus over the final death toll.

Looking at the work of progressive photojournalists, such as Indian Sunil Janah (1918?2012) and American William Vandivert (1912?1989) who both documented the tragedy at close range, one is re-sensitised to the shocking degradation. Archives also include images from anonymous photographers who captured entire families, emaciated, waiting for death to occur. Abedin?s own boldly simple, black ink ?recordings? on wrapping paper illustrate the full force of his sharp and measured protest; a special kind of artistic objectivity that fuelled his revolutionary shift to social realism and testified not to a shortage of food but to the ruthless withdrawal of its proper distribution. The artist?s universal human figures and gestures become the very metaphors of compassion, as well as a speechless indictment of the systems that allowed an entire population to perish. His valiant brushstrokes deal an unforgettable blow to spectators and perpetrators alike. Contrasting his softer, idealistic works, we see him breaking free from the prevalent academic prescriptions of his time to establish a truly individual style.

Abedin?s final masterpiece Struggle (1976) also provides a visual counterpart for the Bengali poet Jasimuddin (1903?1976), known in Bangladesh as ?Polli Kobi? (the rural poet), as both depicted the injustices behind an arcadian view of rural life; emphasised in this rendition:?

O Bajan, Chal, Jai Chal Mathe Langol Baite

O father come let us go

To the field to plough,

Place the ploughs on oxen shoulders and

Push, push, push.

We who bring out food

From the depths of the earth,

We who provide food for the whole world,

Why can?t we eat, can anyone tell us?

My wife has hanged herself,

She could no longer bear hunger,

Now I plough deep into the soil

In the hope of seeing her again.

We plough the fields,

Our bosom is always flayed,

But from the fields we get harvest,

None from the sacred bosom.

We shall plough no more for rice,

But to see how far it is to the graves.[3]

Can art generate new ideals that in turn action social progress? Can it function as a vehicle for cultural solidarity in the face of political maladies? Zainul Abedin was surely an agent of change. After Partition many Muslim artists educated at the Calcutta Government Art School moved to Dhaka. Given the role of art in the context of religious restrictions and political chaos at the time, Abedin?s ambitions to develop society stand out prominently. Defying Platonic condemnations of art as imitation, Romantic poets like Friedrich Schiller (1759?1805) and Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792?1822) insisted on art?s power to change the world through its ennobling images of beauty, morality, and justice. Schiller made art central to his project for the ?aesthetic education of man?, and Shelley likewise argued that ?poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.?[4] Abedin?s iconic imagery of a paradise lost wields an indelible ink-brush of truth, often presenting a double-edged dilemma. Our almost visceral tendencies to accept clich?s in preference to what is complicated or intricate has resulted in much ignorance about our fellow human beings. Abedin was a true insider, fully qualified to represent the local men, women, and children of his land. His interactions with the West were pivotal in terms of his own education and development, but more importantly so for his self-appointed ambassadorial role in distinguishing Bengali aesthetics and later Bangladeshi culture. Essentially a man of the people, believing one?s voice emerges from one?s own desires and resources, he did not genuflect to Western ideals. Bengal had no need to adopt poetry, music and art. Its folk traditions could be effectively integrated into a worldly modernity. In this sense, Abedin was instrumental in constructing a local identity for the ?craft? of image making. Travelling the roads of Bangladesh and staying in the homes of artists, writers, and collectors, you realise there is so much more to the misery projected by conventional media. In watercolours like Kalboishakhi (1950), Waiting for the Ferry to Cross the Brahmaputra (1951), and Levelling the Ploughed Field (1959), there is no landscape per se, since the context is unyielding and timeless. They are more about movement, atmosphere, and human tenacity; uninvested in depicting archetypal victims and more intentioned on empowering alternatives to received notions of the subcontinent; a kind of counter-colonial response to Western perceptions. Since culture cannot be partitioned, Abedin asks us to understand rather than judge, to celebrate rather than compete. His natural empathy and personal access had an edge, ensuring the story is not misread. Among others, he also pioneered new representations of what were hitherto seen as ?foreign? realities through Western eyes. If he left a tangible legacy for the emergence of contemporary ?indigenous artists? it is because they are able to achieve an intimacy with their subjects that enhances the credibility and eloquence of their work.

Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin Sangrahashala. Mymensingh.

Like another of Bangladesh?s national treasures, Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899?1976), ?Bidrohi Kobi? (the rebel poet), Zainul Abedin worked for a common cause: to serve the people through art. A home grown revolutionary and composer, Nazrul edited the politico-cultural magazine Dhumketu (Comet). A political poem published in September 1922 led to a police raid on the magazine?s office and his subsequent arrest. In April 1923 he was transferred from the Alipur jail to Hooghly in Kolkata, and there began fasting to protest mistreatment by the British jail superintendent. He broke his fast over a month later and was eventually released from prison in December 1923. During his imprisonment, Nazrul composed many poems and songs that were banned in the 1920s by the British authorities. While Nazrul was fifteen years the senior, he and Zainul both died in the same year. Correlating Abedin?s personal mission with Nazrul?s revolutionary calls, we see how artists, across different mediums, can be effective conduits for social change and catalysts for positive transformation in collective consciousness. Both aimed to re-sensitise the human spirit, eradicate ugliness ? economic, social, or visual ? and restore beauty as a daily practice. Both spotlighted the suffering of commoners at the hands of ruling elites and the need for drastic changes in our social systems. Indeed, many an artist, across time scales, cultures, beliefs, and geography, may find their echo in these inspiring sentiments from Nazrul?s plea in court:

?My voice is but a medium for Truth, the message of God… I am the instrument of that eternal self-evident truth, an instrument that voices forth the message of the ever-true? The instrument is not unbreakable, but who is there to break God?? [5]

Rosa Maria Falvo

International Commissions Editor

Skira Publishing Milan

1 For a detailed account of this geography see Willem van Schendel?s A History of Bangladesh, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

2 BBC Radio 4 series The Things We Forgot To Remember, originally broadcast on 7 January 2008, involved Newsviner Dr Gideon Polya, Professor Amartya Sen, and other scholars, who each revealed how this man-made atrocity took the lives of over four million Bengalis, but remains largely omitted from world history.

3 Jasimuddin?s lyrics are here translated by Hasna Jasimuddin Moudud, daughter of the poet, who is also the author of A Thousand Year Old Bengali Mystic Poetry, University Press Ltd., Bangladesh, 1992.

4 F. Schiller, On the Aesthetic Education of Man, bilingual ed., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1982, and P.B. Shelley, ?Defence of Poetry?, in H. Adams (ed.) Critical Theory Since Plato, Harcourt Brace, New York, 1971.

5. From an article by Mohammad Shafiqul Islam in The Daily Star, ?Remembering Nazrul 34th death anniversary of the National Poet: Life and times of a rebel?, 27 August 2010.

?

?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.