Foreword by Shahidul Alam

?Kill three million of them,? said President Yahya Khan at the February conference (of the generals), ?and the rest will eat out of our hands.?

The executioners stood on the pier, shooting down at the compact bunches of prisoners wading in the water. There were screams in the hot night air, and then silence. (Payne, Massacre [Macmillan, 1973], p. 50, p 55.)

There were to be no witnesses to the massacre. The foreign journalists had all been sent back. The media had been taken over.. Those of us in East Pakistan, Bangalis, Paharis, Muslims, Hindus, Christians, Buddhists, were all labeled Kafirs. The genocide was to be presented as a holy war. They expected no resistance to ?Operation Searchlight? They couldn?t have been more wrong. The brutality was unparalleled, but so was the resistance.

The national elections of 1970 had been the beginning of the army?s rude awakening. As is often the case with autocrats, the general had misgauged the popularity of the Awami League and had not foreseen either the people?s resolve, or their ability to fight back.

The clock started on the 25th March 1971. It was within the space of a month that the entire opposition was to be decimated. The opposition newspapers, the para-militia and the University bore the brunt of the first assault. The local collaborators of the Pakistani Army, the Al Badr and Al Shams ran amok. Death squads ruled the cities.

The exodus of ten million people is difficult to ignore. Despite the media blockade, word got out. Then came the second surprise. Resistance grew.

Their actions became more desperate. Rapes and killings intensified. Entire villages were burnt. The random killings were augmented with targeted assassinations aimed at instilling fear and establishing authority. Here too, they miscalculated. Rather than ?eating out of their hands?, the Mukti Bahini (freedom fighters), many of them supported, trained and armed by the Indian army, slowly gelled into a more cohesive fighting force. It was a people?s war and ordinary women and men performed extraordinary acts of heroism. Mujib had called for ?every home becoming a fortress?. The fear was now in the oppressors? eyes.

In a last act of desperation, Pakistan preemptively attacked Indian airbases on the 3rd December 1971. This opened the floodgates. With India declaring war, the Mukti Bahini now had the open support of the Indian military. The nine-month guerilla war transformed into an all out attack to vanquish the oppressor. The Pakistani army surrendered with 93,000 soldiers. While the 13-day war is considered one of the shortest in history, it took a huge toll on Bangladesh. In their dying throes, the Pakistani army and their collaborators began a selective campaign to kill the intelligentsia of Bangladesh, aiming to destroy the ability of the – now inevitable – new nation, to recover.

Much of this was discovered afterwards, when the mass graves were found. It is impossible to know how many such graves there were. New ones have been found even 28 years after the war. During these long nine months, the world wept for Bangladesh. While it is true that the US government sent the 7th Fleet to the Bay of Bengal in support of Pakistan and Henry Kissinger sent a message to General Yahya Khan, thanking him for his “delicacy and tact,” Archer Blood, the US Consul General in Dhaka, despatched his famous Blood Telegrams, accurately articulating the horrors that were being perpetrated. Joan Baez, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, George Harrison Billy Preston, Leon Russel, Ravi Shankar, Ringo Starr and many others had gathered at Madison Square Garden in New York, to an audience of over forty thousand, to voice their protest and express their solidarity to the Bangladeshi cause. George Harrison?s song ?Bangladesh? and Allen Ginsberg?s poem ?September on Jessore Road? galvanised world opinion and became the rallying cry for resistance.

Some of the finest photojournalists of the world also came. Remarkably, while it was one of the most richly documented popular struggles of modern times, very few compilations exist which provide an overview of the epic struggle. The Bangladeshi photographers were too vulnerable to make their work public. Some gave away undeveloped films to foreign journalists in the hope that they might make a difference. None of those films ever made it back to them. The books and films that were produced for Vietnam, were never replicated for Bangladesh. The foreign publications where images were used, were not available for the Bangladeshi public to see. US Filmmaker Liar Levin followed a cultural group which sang songs for the Muktis during the war. The raw footage, remained in his archives for many years until filmmaker couple Tareque and Catherine Masud created a compelling story ?Muktir Gaan? (the song of freedom) combining fresh imagery with the archived footage.

The history of the war has been contested, with different individuals and parties trying to make political capital out of the sacrifices of millions. Photographic archives are slowly emerging. Some by Bangladeshi professionals and amateurs, who took enormous risks to preserve moments in history. The recently found archives of the legendary Indian photographer Raghu Rai, is undoubtedly one of the most significant of these.

As we began compiling the work of 1971, I had written, ?They had risked all to hold on to this moment in history. The scarred negatives, hidden from the military, wrapped in old cloth, buried underground, also bore the wounds of war. These photographers were the only soldiers who preserved tangible memories of our war of liberation. A contested memory that politicians fight over, in their battle for supremacy. These faded images, war weary, bloodied in battle, provide the only record of what was witnessed. Nearly four decades later, they speak.?

Few speak more poignantly than the negatives of Raghu Rai.

It was in 1986, on a junk headed for Kowloon where we met. I was young and inexperienced and somewhat in awe of the great Indian photographer. The judging that we?d been invited for, finished early, and instead of hanging around for the entertainment the organizers had arranged for us, the two of us decided to make our way to mainland China. It was in those short hectic days of intense work in the streets of Guangzhou that I got to know this incredibly talented photographer.

His unassuming presence and his comraderie had given me no indication of what

Raghu Rai? meant in India. Of course I knew he was a celebrity, but I?d come across other celebrities and thought I knew what to expect.

I was clutching a book Raghu had given me a couple of days earlier in Delhi as I went through Kolkata airport. The customs officer, catching a glimpse of the author?s name, asked if he could look at it. I had learnt never to argue with customs officers, but it was nice to find a one more interested in my photography book than any taxable items I might be carrying.

He beckoned his colleagues and as all passengers stood in their lines, the officers pored over each page, lingering on some, gasping at others, until they had gotten through the entire book. One person turning the pages while the others crowded in a tight half circle, eager to catch a glimpse.

With profuse apologies, the man politely handed me back the book, and waved me and other passengers on. I have tasted this Raghu phenomenon on both sides of the border. When we ran workshops together in India, or when he came over to teach in our school of photography, Pathshala. Star struck students hung on to every word. The exhibitions that he showed were hugely popular not only with photographers, but with others who normally showed little interest in the medium. So when the phone rang during a class I was taking at Pathshala and I recognized the number, I broke our normal code of conduct to answer.

The familiar voice had a youthful excitement. It took a while to sink in. But soon it was I who had to contain myself. It was a treasure trove of unimagined proportions that Raghu was talking about. His negatives of 39 years ago had been found. The 1971 negatives that he himself had thought were lost. He had not yet informed anyone else. The enormity of the find was something he knew I would appreciate.

I remember Goksin Sipahiouglu, in the Paris office of Sipa, showing me the first ever colour slides of ?71 I?d ever seen. Meeting up with Abbas by the seaside in Manila, talking to Don McCullin in a back garden in Arle, finding David Burnett?s diary in the basement of the Time Life archives were all memorable events. But none of that came anywhere near the excitement this discovery was generating.

The PDF file arrived through yousendit a few days later. What a treasure trove it was! As a photographer, the significance of newfound work by the great image maker would have been exciting in itself. While reliving the torment was painful, I couldn?t help being awed by the enormity of the find. And what a find!

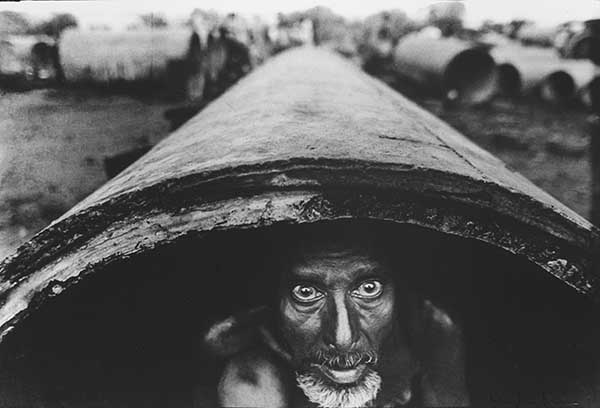

The stories were not unknown, but to be retold by a master story-teller with all the dexterity of an African griot, had a charm quite its own. The refugee camps, the exodus, the desperate helping the desperate, the sewer pipe homes, the never-ending journey, and the eyes, oh the eyes. Haunting, beseeching, forgiving, groping, longing, swirling in the whirlwind of a poignant tormented history, the weeping, tender, sometimes lost eyes still had an intensity that was hard to imagine, even harder to describe. But that is precisely what the photographs did. While reminding us of the misery and grief and the utter desolation of their lives, the eyes, reminded us that they still held dreams. A new nation, a new tomorrow. Torn lives waiting to be sewn together. Waiting for a new nation to be born.

And there were shapes, elliptical forms draped in coarse cloth. A covered head, a sheltered body, a draped corpse, a futile gesture making imaginary shapes in an unseen horizon. Trying to make sense of a politics where their lives were dispensable.

And there was movement. Monumentous journeys, never ending flows. People reduced to numbers. Trundling, dragging, flowing, ebbing, weaving between bodies, holding on, letting go. Reluctantly walking on. Looking back. Not looking back. Bare feet on slippery paths. Food lines. Bent bamboo across bent backs carrying bent bodies on bent trajectories. Straddlers on bumpers, huddled in rooftops, crammed in unyielding doorways. The never ending convoys snaking through uncertain paths. A solitary gun, old and muddied, peeping unthreateningly through a bus window as others, unperturbed, look for footholds on dangling projections. Past burning homes, and bloated bodies. There are no divisions here. Mother, child, soldier, leader, are all on the same journey. All needing one another. All one wronged family. Weary bodies needing rest, but ready to fight.

They say photographs tell more of the observer than the observed. It is this gentle but probing eye that holds these frames together. An eye that watches, from close up, but ever so lightly. Raghu tiptoes delicately through this muddy path. Careful not to let his penetrating gaze leave shards that might cut. But the gaze is unrelenting all the same. A lonely mother by the root of a giant banyan tree, is as carefully lifted onto his frame, as the smiling muktijoddha playing with his new found pet rabbit. It is the human condition stripped bare. Revealing all, but still holding secrets. Secrets in those eyes, that carry the burden of near ones lost, of homes torn asunder, of journeys leading nowhere. Eyes that close without sleeping.

Bodies huddled in camps, Gaunt frames held together by courage, look at and through the photographer. Seeing far beyond.

There is hope and passion too. Young boys with oversize helmets preparing for war. Rickshaws with fluttering flags. Soldiers, farmers, boatmen all warriors under the same march. Different convoys, more strident, raising dust, readying for engagement. Raghu reminds us of the many faces of war. Through charred bodies and bullet holes, we are led to victory. As in all wars, a painful victory. The finality of surrender.

And then there is joy. Jubilant crowds tasting freedom. Raised salutes, victorious leaders. The joy of liberation, soured with the agony of loss. Freedom, but at a price.

These are historical images whose significance cannot be ignored. But the vignettes of human interaction make up his signature images. He photographs the generals waist up, but the difference in stride is clearly discernible. The victor and the vanquished. This is vintage Rai, reminiscent of his photograph of Indira Gandhi surrounded by her cabinet. A master photographer using every nuance of the medium to its fullest potential.

There is the sadness of loss, and the joy of victory, but there is no staged heroic imagery. Rai photographs the frailty of people, even fighters. An unsure young Mukti, barely taller than his gun stands by a fluttering flag. His posture giving away his rural origins. These are the heroes who will never have roads named after them. Who will never assert their ?rights? as muktijoddhas. Who will return to the paddy fields. It is this ability to capture the quintessential moment, where a fraction of a second becomes the unique signifier of a time. The fleeting moment that becomes timeless, that makes Rai the artist that he is. It is not a war that he has photographed, but humanity itself.

Please Retweet #photography #Bangladesh #1971 #magnum

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.