Nelson Mandela’s release from prison 20 years ago opened negotiations which finally ended the racist segregation of the apartheid system. The BBC’s diplomatic editor James Robbins, who was in Cape Town to report on the release, has been back to talk to key figures in the country’s transformation.

“Nelson Mandela’s first steps back to freedom…”

I can vividly remember the excitement of being able to say those words as I reported on the moment that transformed South Africa for ever? as Nelson Mandela started that long walk which eventually led him from prison to the Presidency.

Nelson Mandela had spent more than half his adult life in prison. As he walked to freedom, already 71 years old, his largest task still lay ahead. The ANC leader had to negotiate an end to white rule. Twenty years on, I returned to Cape Town to look back with FW de Klerk – the last white President and the man who finally set Nelson Mandela free – and to revisit Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who led the protest the helped make Nelson Mandela’s release inevitable.

Mr de Klerk is in no doubt about the significance of his decisions to unban the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party and to free Mr Mandela at last:

“I realised that after the announcements which I made, South Africa would be changed for ever.”

‘Blessed’

Archbishop Desmond Tutu heaped praise on Mr de Klerk for breaking the white stranglehold on power. “He deserves all the credit that you can imagine. He showed incredible courage,” the Archbishop said. “Not every country has a Nelson Mandela. We were blessed, I think. We could so easily have gone up in flames.”

And I’ve been back to one of those black townships in the Cape – which was so often in flames. I often used to go there to report violent clashes with the army and police.

At the time, they fired shotguns from their armoured vehicles, or charged with teargas and whips at anyone daring to demand basic rights in a racist society.

This time, I’m meeting Zongs Liwani. He was one of those protesters. He was just 21 years old when Nelson Mandela was released, and he went to the City Hall in Cape Town to see him that first day. Zongs realised immediately that his life, too, could change:

“The way Nelson Mandela was so sure or – how could I put it? – aggressive about changing South Africa, I knew that he would actually come out and make a difference,” he said.

Poor but free

And the difference for Zongs himself? He proudly took me into the new township supermarket. It’s large, it’s thriving and it’s his.

“I’m standing in my own shop,” he said.

So I asked him if something on this scale could have happened under apartheid. His view is clear: “That was something way far from us getting into then.”

Outside, though, much in Nyanga has not changed. There are many of the same shacks and leaking corrugated iron roofs. There is still a housing crisis in South Africa. There are still squatters living here. There’s still poverty, but at least the people are free.

I met South Africans with very strong memories of the day Nelson Mandela was released, but the future of the country belongs, of course, to those too young to know that day except as a day in history.

So I went to the University of Cape Town, which was overwhelmingly white when I lived here, to talk to a group of 20-year-olds of all races and backgrounds.

Neliswa Dludla got a place at this prestigious university after a childhood in the townships. She is in no doubt of the disadvantages she had to overcome, including a lack of the sort of support white children have been used to.

“You don’t necessarily have a study room, so you find yourself having to push yourself,” she says.

I asked her if she had had to be a fighter.

“Ya, basically,” she replies.

Her friend Rachel Mazower, who is from a privileged white background, is delighted to be growing up in a free, non-racial South Africa, but acknowledges it’s going to be tougher for her.

“Oh, definitely it’s more difficult for us than my parents’ generation,” she said. “They tell me they just had to scrape through everything. The best jobs were guaranteed for them in those days.”

‘Need for reconciliation’

It’s?left to Lynn Leigh-Brandt to inject one note of caution. She’s hesitant about voicing it, but then:

“OK, I’ll be completely honest? What if Nelson Mandela dies? What could happen,” she says.

“Is it still going to be equality for all? Will there still be black economic empowerment?”

And Lynn readily agreed when I suggested that Nelson Mandela was such a unifying force that people behave better as long as he’s here.

The last words belong to the former President and the Archbishop.

FW de Klerk is in no doubt: “The commemoration of Mr Mandela’s release. It reminds us all of the need for reconciliation,” he says.

And Archbishop Desmond Tutu gives me a huge smile at the end of our interview:

“Hey man, God took some time creating God’s own country,” he breaks into a huge, rolling, infectious laugh.

“Fantastic country? fantastic country.”

———-

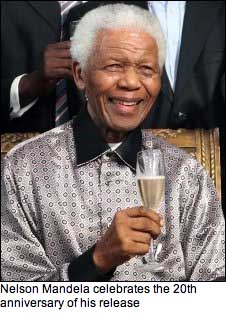

My meeting with Mandela on his 91st birthday

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.