By rahnuma ahmed

Story-telling often helps convey the message more sharply, more pointedly than lengthy passages full of heavy prose.

A friend’s daughter, who is British and of Bangladeshi parentage, works in the British army. She’s such a darling, such a wonderful, loving little soul, said another friend to me. I’m sure she is, and I really look forward to meeting her — a friend’s daughter, after all, is like one’s own daughter — but what’s she doing working in the British army?

Well, I don’t see any problem, she replied, shrugging her shoulders. That’s work, and as long as she’s happy with it…

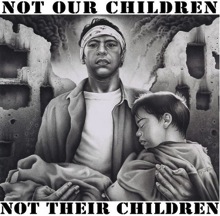

But do you think that’s how Iraqis and Afghanis view it? We didn’t in 71, why, rajakar (local war collaborators) is still a hated word. Being Bangladeshis, we know what occupation by colonial forces means, we know what resistance means — the pride it lends, the ability to fight back, the dignity in resisting foreign rule. If this was 1971, and if the British forces had been here in support of the Pakistan army, how do you think we would have viewed their presence? Surely not as, oh, they’re here doing their job, just getting on with their lives and their careers, its nothing to get upset about…? If we value 1971 because it represents an epochal moment in 20th century world history, because the people of East Pakistan had risen up to fight against (internal) colonial occupation, we cannot not respect, we cannot not lend our moral support to the people of Iraq and Afghanistan who resist western occupation. We cannot not support the people of Palestine whose lands have been stolen by the Israelis. Neejerta buzbo onnerta buzbona… How can one justify grieving for one’s own war losses forty years on but persist in remaining oblivious to that of others?

Interestingly enough, I’d met an American couple a week earlier whose son, in the US army, had been deployed in Iraq. Not once, but twice. He’s back home now, said his mother. We’re both pacifists, we’ve always been pacifists. Her husband, seated next to her, nodded his head. We believe, and very strongly too, that war is not justified. Period.

So, how’s your son now? I asked. Fractured, replied his mother, he will remain so for the rest of his life. There’s no escaping the fact. I can sense it, being his mother. He’s my son, I love him, it was his choice, but…

I lowered my eyes for there was an indescribable look of pain and sorrow in her eyes. Her gaze, even though she was still looking at me, had turned away, seemingly inwards, but in another sense, outwards. At what lay ahead? We fell silent. I got up and hugged her later.

To get back to the sense of Bengali exceptionalism that prevails (that is made to prevail) — our muktijuddho is unique and unparalleled, it is not comparable to that waged by any other people anywhere else in the world. But this had not been the case in 1971, nor, in the years preceding ’71, when it had become increasingly clear that Pakistan’s military dictators and US allies, general Yahya Khan, preceded by field marshal Ayub Khan (in the latter’s own words, the “most allied ally” of the US), had wanted to rule by force.

American imperialists, as this poem by the Ekushe Padak winning poet Nirmalendu Goon, expresses so cuttingly, were loathed, deemed worthy of the worst afflictions that could befall war-mongers:

The Curse

Should my words foretell, as of an ancient sage

Should my gaze set ablaze, the palace of kings;

Should the heartless butcher, lie impaled by my curse,

Should leprosy tear his flesh apart

If my thoughts could seed, plague ever so vile –

Above all would I curse, vulture from afar

Eyes dripping lust on gentlest maiden

Asia?s land, its map scarred and bleeding

Its claws oozing with flesh

(Prothom Diner Shurjo, 1962-69)

[translated by Shahidul Alam at my request]

The vulture from afar swooped not only on Asia, but on other continents as well. The poet, a voice of protest against the wounds inflicted on his world (amar ahoto prithibi) arouses ‘the desired awakening’ (ipshito jagoron) among the oppressed multitudes in far-off lands, only to streak back to ‘his native imprisoned land with the [wounded] world’ in his wake (bondi shodeshe je prithibi tani). To proceed to awaken ‘funeral pyres’ (Ami daak dei, hey shoshan tumi jago) and ‘graves’ (Ami daak dei, hey kobor tumi jago), so that those ‘detested’ can wear the crown of victory one day (ghrinito manush ekdeen pabe bijoyir shomman). Goon writes in the Song of the Commons,

Twigs as I gather, new nest I build n?other, in Africa Asia, Latin America

Through people I embark, light hurtling through dark

Souls that I?ve touched, millions rising as one

A million lives lit up, still to my own land return

(Banglar Mati, Banglar Jol, 1978)

[this too, has been translated by Shahidul]

Has “the vulture” disappeared from public consciousness in the last forty years, since we won independence? Do members of the public too, regard themselves as islands, untouched and aloof from the present miseries of scarred and bleeding others elsewhere? No, not really, for I remember garlands of worn-out footwear strung around the neck of a scarecrow in more than one paddyfield, with ‘Bush’ lettered on its chest as I travelled from Dhaka to Chittagong, just before the US-led forces invaded Iraq in 2003. A similar sight greeted me in parts of Dhaka city where I hadn’t expected it: a scarecrow plonked in the middle of a road divider in Dhanmondi; yet another, in Gulshan. Torn shoes and sandals were strung around its neck and shoulders, the reviled letters ‘Bush’ greeted passersby.

Has “the vulture” disappeared from public consciousness? Does resistance to foreign occupation elsewhere not evoke feelings of solidarity here? I think it does, for I remember a cobbler outside New Market where, as part of a group of largely university and cultural activists, we had embarked on a mass signature campaign in Dhaka in early 2003 to protest against Yasser Arafat’s confinement in Ramallah (2002-2004). “Of course I will sign, the Palestinians have been suffering for so long, Arafat is their leader.”

I remember too the chotpotiwala who I met more than a year later, when we’d been busy plastering posters on Dhaka University premises protesting against the invasion of Iraq. Engrossed in washing stacks of tin plates and spoons, he looked up, curious at the small band of men and women running around, looking for empty wall spaces in the middle of the night. I walked over, explained to him why we were there, and asked, “So, how are you, brother?” I haven’t forgotten his reply, “I musn’t complain when I think of what the Iraqis are going through, of how difficult it must be for a common Iraqi to feed his wife and children. Of how everything must be falling apart because their land and freedom have been taken away.”

In the ultimate analysis, it is common peoples’ resistance which protects national independence. New forks have been created as those who are socially privileged, benefiting vastly from neo-liberalism’s privatisation, turn muktijuddho into an object: de- historicised, de-contextualised. As, sections of the socially privileged, otherwise holding divergent political ideologies, converge in the belief that colluding with imperialist wars will help defeat the forces of “religious fundamentalism”, lazily elided with social forces represented by 1971’s rajakars. I say lazy because they choose to ignore the fact that the “modern international movement of political Islam is largely the product of Western funding and encouragement, intended as a weapon against secular and left nationalist regimes and movements.” Hester Eisenstein (2005) is not mistaken, because Afghan mujahideens received CIA training, were feted at the White House by Ronald Reagan who, in 1982, dedicated space shuttle Columbia to Afghanistan’s resistance fighters. Because, as Malalai Joya, former Afghan parliamentarian points out, US government policies foster warlords and criminals, it marginalises and puts pressure on progressive and democratic movements and individuals “out of fear that the latter will mobilise Afghan people against the occupation forces.” Because, al-Qaeda is Nato’s ally in Libya.

New forks have been created as Awami League’s vast array of sycophantic intellectuals choose to ignore that those who were our “friends” during the muktijuddho are no longer so (take-over of business, disputes over shared water resources, border killings, Bollywood mega-star Shahrukh Khan’s sala to Dhaka’s noveau riche audience evokes glee).

New forks have been created as US Special Forces, we learn from recent press reports of Congressional hearings (not from our government), are here, on Bangladesh’s soil.

One increasingly hears that muktijuddho is far from over. But the next time round, the battle lines will be drawn against new enemies. Their local collaborators too, will be new faces.

—————-

Published in New Age, on Independence Day Monday March 26, 2012

thanks you a my teacher i ithink you was came in Tanzania 2004 for the World Pressphot Training iam among of them