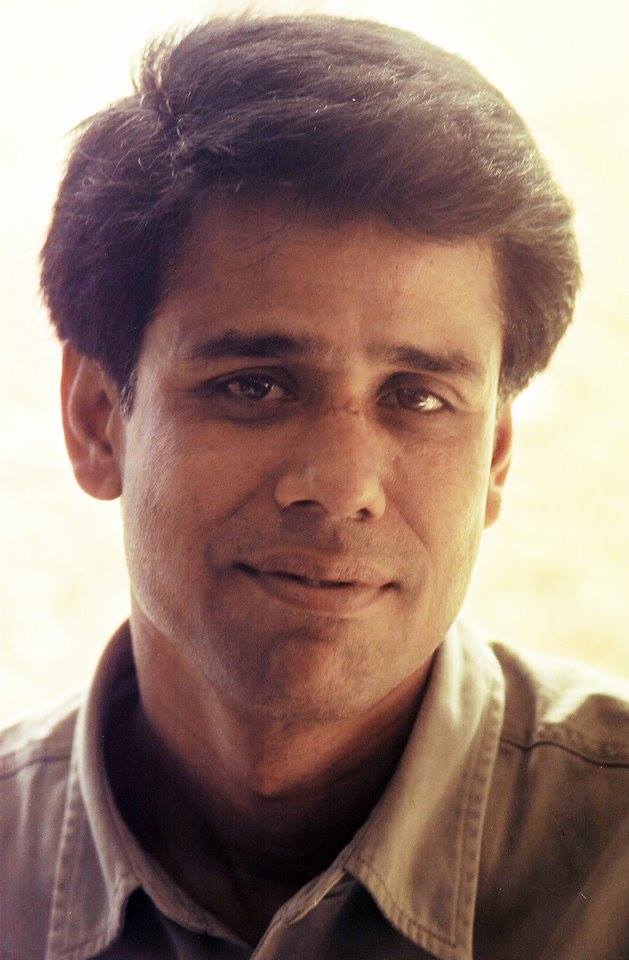

AZIZUR RAHIM PEU, born 10th June 1964, died 14 October 2014

“If you let me go, I’ll kill myself.” I’d never given a job to anyone before. So this response to my suggestion that there was a better future for him elsewhere, was something I wasn’t prepared for. I had returned to Bangladesh after having been away for twelve years. Not having the capital myself, I had set up a photographic studio in partnership with a businessman cum photographer Khan Mohammad Ameer and his businessmen brothers. The studio ‘Fotoworld’ was posh, and we photographed the glitterati. We also took pictures of factories, the odd milk powder tin, food, cigarette cartons and pretty much anything people would pay us (and sometimes not pay us) to shoot. Azizur Rahim Peu was my first recruit. I’d come to know him through the Bangladesh Photographic Society, where I was the general secretary and had taken an immediate liking to the young man.The businessmen had the lion’s share of the company. I was a glorified director and had little say in the way the company was run. But within the studio itself Peu, a later recruit, Rafiqur Rahim Reku, and I, pretty much ruled. We worked long hours for little pay, argued hard, and learnt on the job. We also had fun.

I could quickly see however, that this job was not for us. We all wanted to be photojournalists and while Fotoworld had promise, it would not lead to the photography we were seeking. I took the decision of going freelance, but felt I couldn’t risk taking on two salaried people on an uncertain income. I suggested to Peu and Reku that I’d help them get jobs elsewhere. We’d still work loosely together, but pointed out that depending upon a freelancer for regular salaries was simply not sensible. They needed a more stable income. Reku saw that it made sense. Peu was having none of it. He would stay with me, salaried or not. The hand-written note, threatening that he would kill himself if I abandoned him, was perhaps theatrical, but he was making a point. Knowing the reality of freelance life, I called the bluff. I also helped him get a job and we remained close ever since.

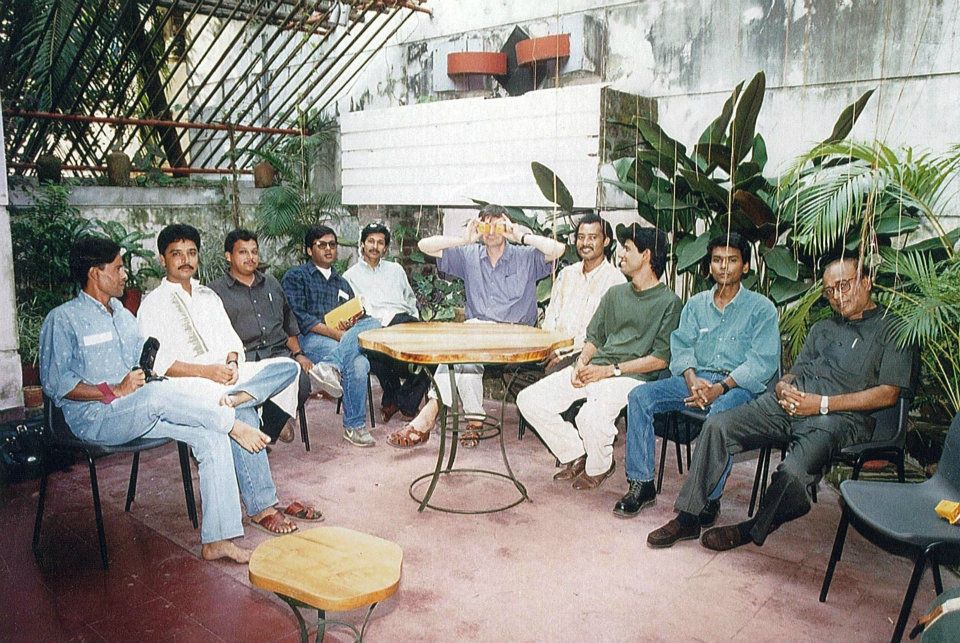

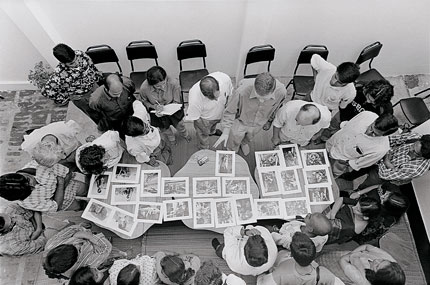

After three terms as president of the Bangladesh Photographic Society, and after having set up the Bangladesh Photographic Institute, I felt a more professional body was needed and went on to set up Drik. Peu was one of the first contributors. Once Drik was hobbling along, I started it’s education wing Pathshala, which has now become an independent academic institution. The school had no track record or money, very little infrastructure, and only me as a tutor, but several bright young people joined the first batch. Peu was again amongst the first to enrol. We started on the 18th December 1998 to coincide with an international seminar we had arranged with the World Press Photo Foundation. The celebrated photojournalist Reza Deghati and the former director of the London office of Magnum, Chris Boot, came as the first tutors. At the end of the three-day workshop, I returned to being the sole tutor. Abir Abdullah, Shafiqul Alam, Munira Morshed Munni, Sameera Haque, Wahidur Rahman Czhoton, Syed Rafique Bin Arshad Ron, GMB Akash, Nayemuzzaman Prince and Badrul and Ronnie (whose full names I’ve forgotten) and of course Peu, got together at the end of the first session to do a parody of a popular song ‘Iskul khuilache re shohidul iskul khuilache’ (A school has opened, a school by Shahidul).? We had bonded in a very special way.

We had started off with the idea of doing a one-year course. At the end of the first year, Peu repeated his earlier act. He was not leaving. This time he’d gotten the other students on his side, and while we had no idea how we’d keep it going, we extended the course.

This “I’m not leaving” mode didn’t stop there. Even after he graduated from Pathshala, Peu wanted to stay on. Initially, he and another student of the first batch, Abir Abdullah, who was then my colleague at Drik, suggested that we should set up a news agency. Peu and Abir took the responsibility of running it. It would create an opportunity for Pathshala students. My job was to provide institutional support, some seed money and be on board as an editor. Munem Wasif, Andrew Biraj, Muniruzzaman, A M Ahad, K M Asad and Wahid Adnan are amongst the leading photojournalists who found their first opportunities at DrikNews.

There was another group of photographers whom Peu had helped, perhaps without even realising it. I had started training a group of working class children in 1994. On the 3rd October, 1994, when I sat with the kids to seriously discuss photography for the first time, it was one of Peu’s photographs, that of the bodies of child garment workers being piled, that I showed them. That image, and the response it created have remained central to my understanding of photojournalism.

In between all this, he decided we needed a book on photojournalism in Bangla. Doing in-depth interviews of the star-studded international faculty that regularly visited Pathshala. Obtaining the permission to use their images and chasing me to edit the book were things he took in his stride. The book Chobi Alor Bhasha (Images, the Language of Light) remains a milestone in Bangladeshi photographic literature.

For several years, Peu taught photojournalism at Pathshala and when he was eventually unable to continue due to other work pressure, he took on the unenviable task of obtaining Pathshala’s accreditation with the National University. He would chase Rashid Talukder, Aftab Ahmed and other senior photographers to lobby on our behalf. And then he’d put me on the back of his motorbike and we’d ride off to Gazipur to see yet another official, to try and push our application to yet another desk. I’m not sure if I was Don Quixote or Sancho Panza, but attacking windmills was a habit we’d both cultivated.

Despite all this, we drifted apart. At least we saw less of each other. My life had become more hectic. Peu himself was more engaged with the Press Club and the journalistic fraternity. It was when I got arrested by the BSF that I realised who my real friends were. Rahnuma had gathered a full army around her and of course my colleagues and students at Drik and Pathshala played an admirable role, but Nurul Kabir, Farooq Sobhan and Peu were the pillars of that movement. While Peu had desisted from taking his life because I had abandoned him, it was he who saved my life when it mattered.

How do you thank a friend for having saved your life? How do you thank a friend anyway? We greeted we hugged and we carried on doing what we do, which was what bonded us in the first place. That was why I would get regular copies of the newspaper Peu had started bringing out. I had always talked of how important it was for Bangladesh to have a first-rate newspaper.

While I have played a role in strengthening photojournalism in Bangladesh, there were areas where I’d spectacularly failed. While a few newspapers have toyed with the role of the photo editor, not a single one has created the post in reality. Picture credits are more frequent than they used to be, but often still goes missing. Plagiarisation is still rampant. In picture terms at least, the Bangladeshi newspaper has a long way to go. While not in a position to bring out this ideal newspaper on his own, Peu was not going to sit by. Having failed to convince me that I should start one, he took the plunge and brought one out, himself. “Baher Shongbad” was a daily that came out of Rangpur. Every few days a bundle would arrive by courier. The last time we met was in New Elephant Road, a short distance from where Fotoworld had once been. He overtook my bicycle to hand over the most recent copy. It was a flimsy publication by national standards. It wasn’t printed on expensive paper. And the editor still handed out copies personally in the street from his motorbike. But it reminded me that lamenting “how good it would be if” was never enough. If you had an idea you believed in, it was your job to make sure it happened.

Baher Shongdab was one such dream. The dreamer is sadly no more, and a friend mourns.

———————————————————————————————————

Azizur Rahim Peu passed away at approximately 3 am on Tuesday the 14th October 2014 in his Dhanmondi residence in Dhaka. He died of cardiac arrest.

Note: Abir Abdullah went on to become Principal of Pathshala and is currently the photo editor of the Daily Prothom Alo, the leading daily in Bangladesh.

So sorry to read of the passing of such a close friend and colleague, who was in at the grass roots of your enterprise. A sad time indeed. You Shahidul and those those close to Azizur will be in mentioned in our prayers.

Ian Wilson and family, Malta

Sorry I’ve been so unresponsive Ian. Trying to weather the storm. One of these days, I shall be there in Malta to see you and your family. Hugs, Shahidul