It was 1988. The flood waters had reached Dhaka, and I needed a boat to get to the head office of the Grameen (Rural) Bank. A soft spoken unassuming gentleman, casually clad, sat at a plain wooden table. There was no air?-conditioning and the fresh breeze flowed freely through the open windows. My posh camera seemed quite out of place here.

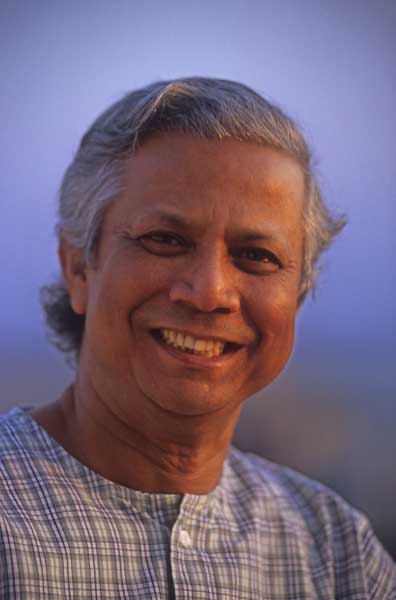

Dr. Muhammed Yunus shook my hands warmly and words flowed easily from the man who had created one of the most remarkable organisations in banking history.

The Grameen Bank gave money only to the poor. Loans to the landless were interest free. None of the debtors had collateral. 75% of the bankwas owned by the landless who could purchase shares of Take 100 (about two pounds; each in 1988. Only one share was allowed per person). The bank boasted 346 branches and 3,000,000 members, 64% of whom were women. Incredibly, about 98% of the loans were returned! It was rapidly expanding and by the following year, Yunus hoped to have 500 branches.

An economics graduate from Vanderbilt University, Yunus had been teaching at Tennessee State University when war broke out in Bangladesh in 1971. He got actively involved in the liberation movement and returned to the newly created nation in 1972 and took up teaching at Chittagong University.

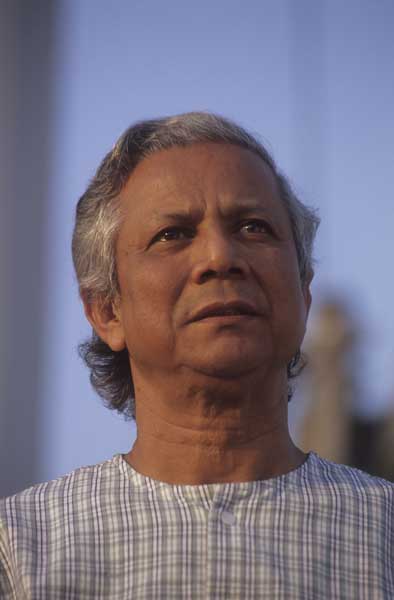

The famine in ’74 touched him deeply. The sight of the dying in the streets made him question the validity of the economic theoories that he espoused. During this soul searching he mixed intimately with the villagers and learnt of their habits, their values and their problems. One of them was a woman who made Moras (bamboo stools). She was skilled and conscientious and worked long hours. He was appalled when he discovered that she earned only eight annas (about one pence) for her daily labour! Angered and dismayed, he sought out the reasons for this shamefully unfair setup.

It had long been claimed that laziness, lack. of skill, and extreme conservativeness was the root cause of poverty in Bangladesh. Here was a woman who was skilled, worked extremely hard and had taken the initiative of setting up a business for herself and was still being cruelly exploited.

She did not have the money to buy the bamboo, so she had to borrow from the trader. He paid a price for the finished stool which was barely the price of the raw materials. She ended up with a penny a day!

With the help of a student Emnath, Yunus made up a list of 42 people who worked under similar conditions. He paid out their total capital requirement of Taka 826 (less than a pound per head) from his own pocket. It was a loan, but it was interest free.

Aware that this was not the real solution to the problem, Yunus approached his local bank manager. The man laughed. The idea of giving money to the poor, and that too without collateral, was to him hilarious. Undeterred, Yunus approached the assistant general manager of Janata Bank:, Chittagong. The manager was encouraging,, but felt that in the absence of collateral, a guarantee by influential people in the village would be necessary. Yunus realised that this would eventually lead to some sort of a slave trade. The bank was adamant, and eventually he talked them into accepting him as the guarantor. The manager was reluctant in the beginning, but felt he could take the risk, the sum being so small.

The system worked, all the loans were repaid and more people were offered loans. Yunus suggested that it was time the bank took over the responsibility themselves and lent out money directly to the villagers.?So I tried to establish that this could be done as a business proposition. I became vocal against the banking institutions, arguing that they were making the rich people richer and keeping the poor people poor through something called collateral. Only a few people could have access to funds. The bankers were not convinced.

Finally they challenged me to do it over a whole district, not just a few villages. They said if I could do it over a whole district, and still come back with a good recovery, then they would reconsider. I accepted their challenge. They asked me to go far away, to where people would not recognise me as a teacher but would instead think I was a banker. So I went to a far flung district in 1978, and started working there.”

It worked beautifully. They had almost a 100% recovery. The small loans made a big difference to the people, but the banks still dragged their feet. Yunus realised that if he went back to the University, the project would die. He suggested the formation of a new bank. One owned by the people themselves. The banks were skeptical, but he got a lot of public support, and eventuual1y in October ’83, an independent bank called the Grameen Bank was formed.

Dr. Yunus is modest about his own contribution. Asked if the bank would survive without him, he smiled “Look at what we have achieved, could it ever have been possible without dedication at all levels ??

There is a more important reason for the bank’s survival. Contrary to most other viable commercial banks, this one is truly designed to serve the people.

Always quick to accept innovations, Professor Yunus was the first person to order an email account when we set up Bangladesh’s first email service in the early nineties. He was user number six, the first five accounts being Drik’s internal numbers. Later he ordered the entire Grameen office to be networked and had generic email addresses issued to key personnel.

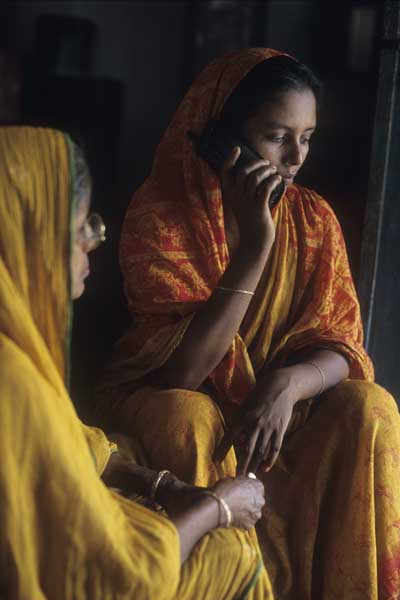

The bank now has nearly six and a half million members, 96% of whom are women. The $ 5.3 billion given out as loans and the $ 4.7 billion recovered are figures any commercial banker would be proud of. Since then other Grameen entities under the more recently formed Grameen Foundation have been born. Grameen Phone, a highly successful telecommunications company has provided phones to rural women, many of whom have become successful entrepreneurs. However both the Grameen Bank and micro-credit have had critics. The high rate of interest is seen to be exploitative by many. There have been accusations that the methods of recovery, often by overzealous bank officials, have led to extreme hardship.

The skyscraper that now houses the bank, many feel, distance it from the poor it represents. The close links with Clinton and Turner, and the uncritical position taken by Yunus in his public interactions with them, has also been viewed with suspicion. Yunus makes light of these observations. Regarding the criticism of his model, he has a simple answer. ?I make no claims to having a perfect system. The problem has to be solved. Should someone come up with a better solution, I would happily adopt it.?

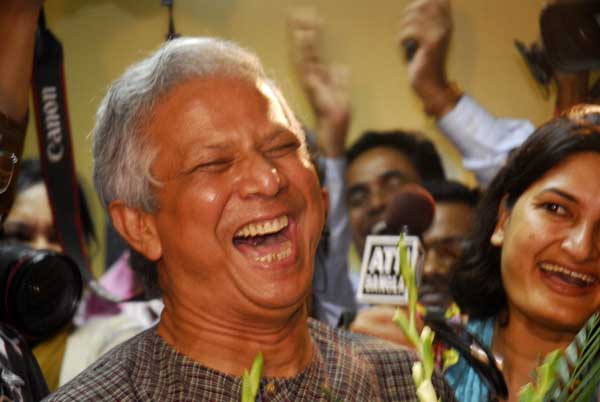

Bangladesh has largely been known for floods famine and other disasters. Yunus has provided Bangladesh with a pride it badly needs. Many had hoped that he would enter politics, providing an alternative to power hungry politicians that people have lost trust in. While he has steered away from mainstream politics, Yunus was an adviser to the caretaker government. That this popular teacher turned banker should be the Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2006 is a source of great joy to Bangladeshis, but an honour they feel was long overdue.

(Photo by Munem Wasif / DrikNEWS)

Shahidul Alam

Drik Picture Library Ltd.

Dhaka 1988 and 2006

High resolution photographs available from Drik Picture Library: library@drik.net

and DrikNews: driknews@gmail.com, driknews@yahoo.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.