![]()

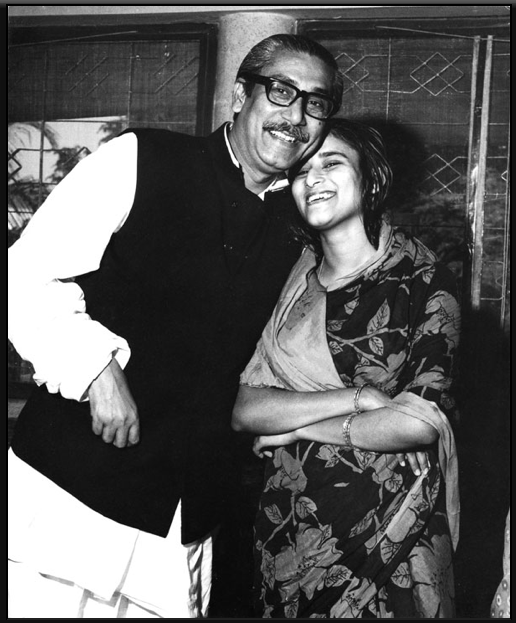

The Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of 1975 was not the Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of 1971. He squandered his unprecedented goodwill for two reasons. First, he could not meet the phenomenal expectations Bangladeshis had in his leadership. Lifschultz, who was based in Dhaka in 1974, remembers the day when Pakistan?s Prime Minister, Zulifikar Ali Bhutto, visited Bangladesh for the first time since its independence from Pakistan. As Bhutto?s motorcade moved from the airport into central Dhaka, a section of the crowd lining the street shouted, ?Bhutto Zindabad (Long Live Bhutto).?

Lifschultz?thought this was rather bizarre. He told me there were conflicted feelings among some Bangladeshis who in 1974 were living through the first stages of a severe famine. Clearly, some believed their hopes had been belied, but to him, the cheering of Bhutto seemed particularly perverse, given the circumstances of Bangladesh?s emergence.

BANGLADESHI FRUSTRATION with Mujib was understandable. By mid-1974, Bangladesh was reeling from a widespread famine that experts believe was at least partly due to political incompetence. Citizens were also stunned by the ostentatious weddings of Mujib?s sons at a time of economic crisis. Food distribution had failed, and people were forced to sell their farm animals to buy rice. Thousands of poor people left their villages looking for work in the cities. Irene Khan, who was until recently the Secretary-General of Amnesty International, was a schoolgirl in the early 1970s. She recalls hungry voices clamouring for food outside the gates of her family home every day.

With?public criticism over the mass starvation growing, Mujib clamped down on dissent. He abolished political parties and created one national party called Bangladesh Krishak Shramik Awami League (BAKSAL); removed freethinking experts who did not agree with his policies; nationalised newspapers (closing most), and allowed only two each?in Bangla and in English. He stifled dissent within the party, suspended the constitution, and declared himself president. Now editor of?The Daily Star, Anam calls those measures the greatest blunder Mujib made. ?It is still a mystery what led him to do that. He had it all. There was nothing, nobody in the parliament opposed to his policies, except for a few voices. He was the tallest man in the country. Why did he do it? It was in total contrast to his political heritage. It was a dramatic transformation from a multiparty system to a one party state.?

The?only time I met Farooq, in 1986, he expressed outrage at those changes, ?How do you pass an amendment in Parliament which abolishes party membership in just 11 minutes? No discussions, nothing!? Bangladesh, in his opinion, was becoming a colony of India, and as a freedom fighter, he thought he had to stop that. ?I tried to save the country,? he told me, his tone rising, ?Mujib had changed the constitution so that the court could not do a thing. All power was with the president.?

None?of Farooq?s explanations justified the terrible manner in which he and his family were killed, but the famine and his increasingly authoritarian rule partly explains why there was little outward expression of grief after his assassination. At the same time, it was not just Mujib?s killing, but the brutality of it, that many Bangladeshis felt justified the death penalty for the assassins.

Justice?moves slowly in Bangladesh. According to a recent study, Bangladesh?s jails can hold only 27,000 prisoners, but there are some 70,000 inmates in jail, and some 47,000 are still awaiting trial, according to the inspector-general of prisons. One reason for the backlog is the shortage of judges. The other is that some defendants are too poor to afford legal help.

The?trial of Mujib?s assassins falls under a different category. There was little political will to try the assassins. That changed when Hasina came to power. The five of- ficers were sentenced to death as early as 1998. They appealed, but higher courts upheld the sentence in April 2001 and November 2009 respectively. They sought a Supreme Court review, and later, four of the five applied for presidential pardon. While the government meticulously followed the constitutional procedures, many have noted the speed with which the final appeals were dealt with.

A?four-member special bench of the Supreme Court?s appellate division met at 9:25 am and issued a verdict at 9:27 am, on 26 January 2010, rejecting the review petition. Senior civil servants of the law and home ministry met at noon, and discussed the issue for three hours. Farooq, who had resisted writing his mercy petition, did so that afternoon. Officials received and dispatched his petition within minutes, as they were all in one room with colleagues whose approval was needed. A report on bdnews24.com said that President Zillur Rahman rejected the petition at 7:30 pm (the hangings occurred soon after midnight).

The?quick turnaround of the documents was remarkable. One lawyer told me, ?What you saw wasn?t due process; it was process with undue speed.?

THERE IS A SENSE IN DHAKA NOW, that the executions have brought the tragedy to a close. Perhaps; but many other wounds continue to fester. On the day of Mujib?s killing in 1975, the officers had also arrested Tajuddin Ahmed, Nazrul Islam, Kamaruzzaman, and Mansur Ali?four leading Awami League politicians suspected of being pro-Mujib. On the night of 3 November 1975, soldiers came to the jail, and asked for the four to be brought to one cell. The jail authorities tried to find out what was going on, when a call from the president asked them to cooperate. The soldiers then took out their weapons, and, without reading out any charges, without any trial or any authority, sprayed bullets on them, killing them instantly. Mosleuddin, involved with the 15 August killings, proudly claimed to have played a role in the jail killings. Khondaker gave the killers immunity. Some pro-Mujib of- ficers overthrew Khondaker two days later. A counter-coup followed, and the situation was stabilised weeks later when Gen Ziaur Rahman took over, ending the pretence of civilian rule. Tajuddin?s daughter, Simeen Hossain Rimi, has compiled her father?s writings and sought justice. The government has said it will pursue that case, too.

And?then there are the war crimes.

When?Hasina came to power in 2008, one of her electoral promises was to seek justice for the victims of the 1971 war. Without getting into the technical debate over whether what happened in Bangladesh in 1971 was a genocide? which is a legal term with a precise meaning in international law?there is enough evidence to prove that both war crimes and crimes against humanity were committed in Bangladesh. Many of those who committed those acts are still free: some live abroad, some in Pakistan and some in Bangladesh, living with the same impunity as some of Mujib?s killers did until recently. These individuals resisted an independent Bangladesh, and successive governments in Bangladesh haven?t pursued the matter. Some governments lacked the political capital and will, some had little moral authority, and some have even been complicit with some of the crimes.

That?context has changed with Hasina?s recent victory. Irene Khan, who worked for many years at the UN High Commission for Refugees before leading Amnesty International, told me:

You can have debates about whether particular acts constitute war crimes or genocide. You can debate whether what happened was a war or an internal con- flict. But they were crimes against humanity. There was obviously culpability and collusion of some locals with the Pakistani army. For instance, in December 1971, before the formal handover to the Indian army, there was a whole list of intellectuals who were picked up and killed. These were not political cases; these were civilians. Those crimes have remained uninvestigated; it is extremely important that there is a commission of inquiry, if Bangladesh is to put a closure to this chapter of its history. Even if you will have only a limited number of prosecutions, you need a full record of what happened.

Pakistan?s?own war inquiry commission report of 1974 mentions that tens of thousands of civilians were killed, and many women were raped. Bangladeshis find that report incomplete because it barely scratches the surface of what happened.

Justice?for those crimes against humanity won?t be easy. At the time of the final handover of Pakistani prisoners of war, India and Bangladesh signed a tripartite treaty with Pakistan, which effectively granted immunity to Pakistani soldiers. While Bangladesh passed a law subsequently to try war criminals, that law only focused on Bangladeshi collaborators, leaving out the Pakistani army. ?That issue has always been brushed under the carpet,? Irene Khan told me. ?The real question is: can an international treaty sign away the rights to justice of victims? The treaty absolves the Pakistani army and political leaders.?

Realpolitik?may have prevented going after Pakistanis, and domestic politics made targeting local collaborators complicated. Hasina?s rival was Khaleda Zia, Ziaur Rahman?s widow. She led the Bangladesh National Party, which has had an electoral alliance with Jamaat-i-Islami, a fundamentalist party. Some of the Jamaat?s leaders and many followers are accused of being collaborationists.

The?Bangladeshi government had said it would commence trials in March. A tribunal was expected to be set up in Dhaka by 26 March, Bangladesh?s Independence Day, but nobody has been indicted yet, no prosecutors or investigators have been appointed, and only Bangladeshi ?collaborators? will be tried. Some observers fear that the process will be seen as an attack on Jamaat-i-Islami. If the initial indictees are only from the Jamaat, they will claim they are being victimised, and the credibility of the process will suffer. A fair process would also investigate the conduct of the Mukti Bahini, the Bangladeshi freedom fighters who are alleged to have committed atrocities against Urdu-speaking Biharis, many of whom supported Pakistan.

And?all this, to what end? It is a people?s quest for justice; a society?s desire to break the imposed silence. It is to reassert the norms that govern a nation, to re-establish the foundations on which civilisation can rest.

Irene?Khan is not sure if the recent executions will help turn the tide against the culture of impunity. ?This is a systemic problem in Bangladesh,? she says. ?There is impunity from the local policeman who beats up a suspected thief, to the security forces who tortured and killed suspected mutineers in interrogation cells.? She refers to the failed Bangladesh Rifles mutiny last year. Guards of Bangladesh Rifles objected to army officers commanding them, so they held officers hostage, killing many of them and ransacking the barracks, before surrendering. Hundreds of mutineers were tortured later, and over 60 died.

THE CULTURE OF IMPUNITY runs deep. Hasina may think of reaching closure for her personal grief. For millions of Bangladeshis, that remains an elusive goal. Projonmo 71 is a social movement, bringing together the children of those who died during the independence war. Staunchly Bengali in their nationalism, many of its members are secular.

Meghna Guhathakurta, an academic who taught international relations at Dhaka University and is now the director of Research Initiatives, a development think tank, is one of them.

She?vividly remembers the midnight of 25 March 1971. Her father, Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta, who was a professor of English at Dhaka University, was correcting examination papers. Schools and colleges were closed, as Bangladeshis had embarked on a non-cooperation movement. She feared her father would get arrested, and they had been warned.

An?army convoy came to the campus. There were six apartments in the building. The soldiers began banging on the doors. An officer and two soldiers entered their ground floor apartment through the back garden. The officer asked in Urdu, ?Where is the professor?? Her mother asked why they wanted to meet her husband. The officer said they had come to take him away.

?Where???she asked. The officer did not reply.

Guhathakurta?told me what followed in a calm voice:

My mother called my father. The officer asked my father if he was the professor. My father said yes. ?We have come to take you,? he said. Meanwhile, several other professors were being brought down. Some families tried to hold them, but we told them??let them go, otherwise they will shoot you.? We turned around, and we heard the firing of guns. And we saw all of them lying in a pool of blood. Some were shouting for water. We rushed out to the front part of our compound. I saw my father lying on the ground. He was fully conscious. He told me they had asked him his name and his religion. He said he was a Hindu, and they gave orders to shoot him. My father was hit by bullets in his neck, his waist, and it left him paralysed. The soldiers had run away. We took my father to the house. We could not take him to the hospital because there was a curfew.

He?remained in pain, and they could only take him to the hospital on 27 March, when the curfew was lifted. He died three days later.

I?asked her about the executions of Mujib?s assassins. ?I am against impunity, and I am very much happy justice has been met,? she said. ?But I am not happy that we have the death penalty. Not every crime has been tried yet.?

She?is a peace activist and has thought of forgiveness, but there is a moral dilemma around that idea. British writer Gillian Slovo, who was born in South Africa, had faced such a moral quandary in the years after apartheid was lifted. During apartheid, Slovo?s father, Joe, led the South African Communist Party, and he and her mother, Ruth, first lived in exile in Mozambique, from where they carried on their anti-apartheid activism. They were among the few whites to take on the South African regime (her mother had been detained without trial in 1963, and the couple fled South Africa after the African National Congress leadership was rounded up). Tragedy struck in Mozambique, when agents of apartheid sent her a letter bomb, which exploded, killing her.

Slovo?ended up confronting the man responsible for sending that lethal parcel to her mother. She discovered a copy of her book, which she had autographed, had ended up with that man. I met Slovo in late 2008, soon after the terrorist attacks in Mumbai, and I asked her if it was possible to forgive. After all, South Africa had astounded the world with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which offered a non-violent way in which the oppressor and victim could resolve differences face to face. Slovo told me, ?Lots of countries like truth commissions because they look at South Africa and think of the miracle. But I am not sure if it was entirely miraculous; it had its flaws, too. The commission was a compromise to stop people from fighting. People need to see if the two sides want to stop fighting first. It is impossible to otherwise start a process that goes so deep. There is a difference between individual and collective responses. South Africa?s experience reflected the thinking of an archbishop [Desmond Tutu], whose church believed in forgiveness.?

Guhathakurta?had studied at a convent, and the Christian ideas of mercy were ingrained in her as a child. She was 15 when her father was murdered, and the impression of those school lessons was strong. She told me, ?I remember the first thing I did was to say: I forgive those who killed my father. But in a multicultural system it doesn?t always work. Not all religions are about forgiveness. Revenge is permitted in many religions. Human beings have a primordial urge to take revenge.?

Many?years later, Guhathakurta was interviewing victims of 1971 for a film. She was talking to those who escaped from killing fields, and families of people who were victims. That?s when it occurred to her: trauma never really ends. Her nightmares will always stay. She acknowledged her anger. She did not want revenge; she wanted justice. She said:

For me, justice would be when the Pakistani government realises what it did. But they have not even recognised the genocide. For me, justice means something like Berlin?s Holocaust Museum is constructed in Islamabad. I want to see signs where they say that such an event took place, and it was our fault, because we did it, and we are sorry. You can?t ask the daughter to forgive the murderer of her father. Revenge doesn?t make sense, either. Just because my father died doesn?t mean yours has to die. But recognition, that something took place, and the fact that it should not take place again? that?s justice. The Holocaust museum says it happened, therefore it can happen again.

Slovo?had put it slightly differently: Real reconciliation only happens when the terrible is acknowledged, so that you can?t say it did not happen.

TOWARDS THE END of the Pakistani writer Kamila Shamsie?s novel,?Kartography, Maheen tells her niece Raheen, ?Bangladesh made us see what we were capable of. No one should ever know what they are capable of. But worse, even worse, is to see it and then pretend you didn?t. The truths we conceal don?t disappear, Raheen, they appear in different forms.?

Bangladesh?abounds with victims?each family has a horror story of its own, where a loved one has been hurt grievously, and the ones who have committed those atrocities have not faced justice, nor expressed remorse. It is impossible to heal everyone. But honest accounting of what happened would be a good start. Trying Mujib?s killers, seeking the extradition of those living abroad and solving the mystery of the jail killings are useful steps in making sense of their warped politics, where individuals bragging about killing defenceless people were being rewarded.

Removing?the culture of impunity will be a small step towards justice?not necessarily through death penalties, but through remorse, forgiveness, and reconciliation. Until that happens, the question Projonmo 71 left inscribed on the plaque commemorating the martyred intellectuals at Rayer Bazaar in Dhaka will continue to resound across the wounded rivers and valleys, awaiting an answer: ?Tomra ja bolechhiley, bolchhey ki ta Bangladesh?? (Is Bangladesh saying what you had wanted to say?)

Previous

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.