“I was tasked with looking after him for 54 years. Now God has taken over that role” said writer Mushtaq Ahmed’s mother. A dignified woman, she spoke in a quiet controlled manner. Occasionally her voice would break, but she contained herself. Refusing to give in to grief. Mushtaq’s dad broke down more openly. He sobbed as he spoke of his children. Of Mushtaq’s farm, of his love of photography. Of Mushtaq’s sister who had been a student in the school my mother had founded. “Can I show you his camera?” he asked me. He gingerly brought over the DSLR camera with a 70-300 mm lens and placed it in front of me. Mushtaq’s wife Lipa, brought out the memory cards and the battery. They were placed in front of me on the dining table, almost as an offering. As I held the camera, Lipa quipped, “the camera was my shotin” (the other wife). “He loved it more than he loved me.”

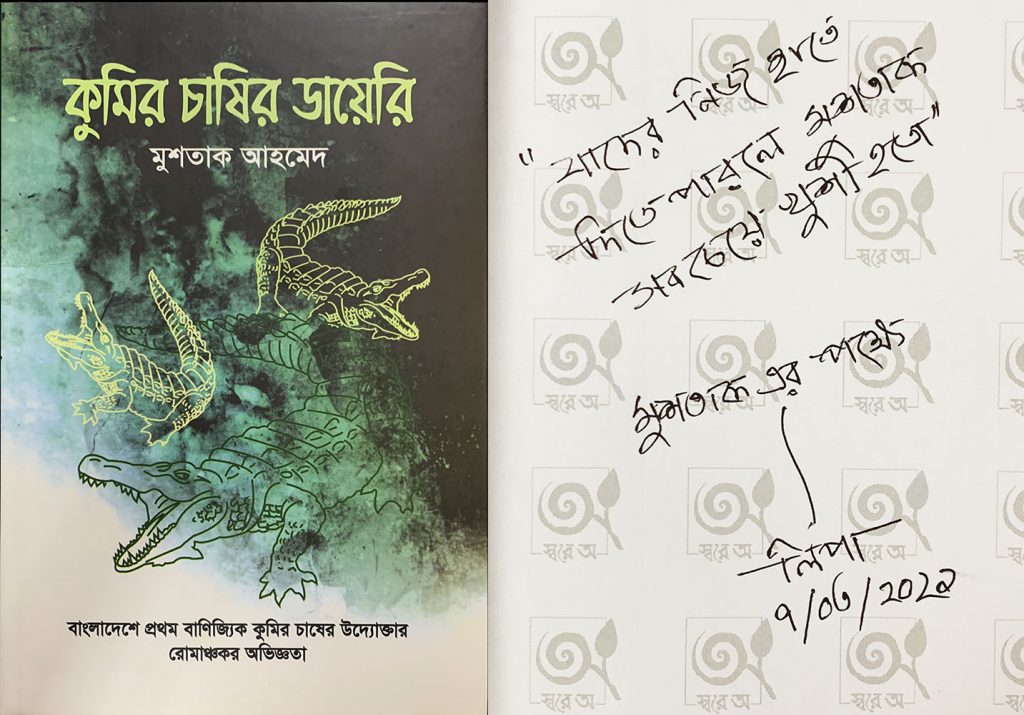

She had earlier gone to get a large print of a mountain range which Mushtaq had photographed. The snowy peaks glistened in the moonlight. Lipa and Mushtaq’s aunt proudly held it up for me to see. “He had so wanted to show it to you. He would have been over the moon, had he known you had visited our home.” She brought over a copy of ‘Kumir Chashir Diary’ (A Crocodile Farmer’s Diary), the last book Mushtaq had brought out. Lovingly she wrote, ‘To those to whom Mushtaq would have so wished to have handed it over himself.’ “It talks about crocodiles, it talks about us too, our marriage. It will help you get to know us.”

She brought over letters from Mushtaq. Seven in all, written from jail, stamped and sealed. Gentle, in neat handwriting, that she had carefully put away, complete with the brown envelopes. “This is all that I have left”.

Skirting over his own precarious condition, telling her instead, ‘dye your hair, go out more, go with whoever you enjoy spending time with.’ Didn’t you write to him, asked Rahnuma. “No, the jailors would have read them, those prying eyes.”

Overhearing conversation Rahnuma commented, you called him ‘Babu’ too. No, no, his parents did, at times I would too, to avoid confusion. What did he call you, she asked. In his letters from jail I saw him write “jaan” (dear heart). “And you?” Nothing, I had always called out “ei” (hey there).

A loving family. Educated, progressive, generous, and immensely proud of their country. The only other time Rahnuma had met them was in the waiting room of the Detective Branch office in Minto road, the night I had been picked up. Mushtaq too had been arrested for having shared my post on Facebook.

As we left, she softly said, “I can’t help thinking, I have you beside me. Lipa no longer has Mushtaq.” Rahnuma is a strong woman. Throughout my incarceration, knowing I’d been tortured, and despite the horrendous vilification campaign, the bail refusals, she had never broken down. Today, I saw her holding back tears.

We will forever be haunted by the knowledge that we didn’t do enough.

Be First to Comment