Rupert Grey, media and copyright lawyer, journalist, photographer and teacher, based in Covent Garden London.

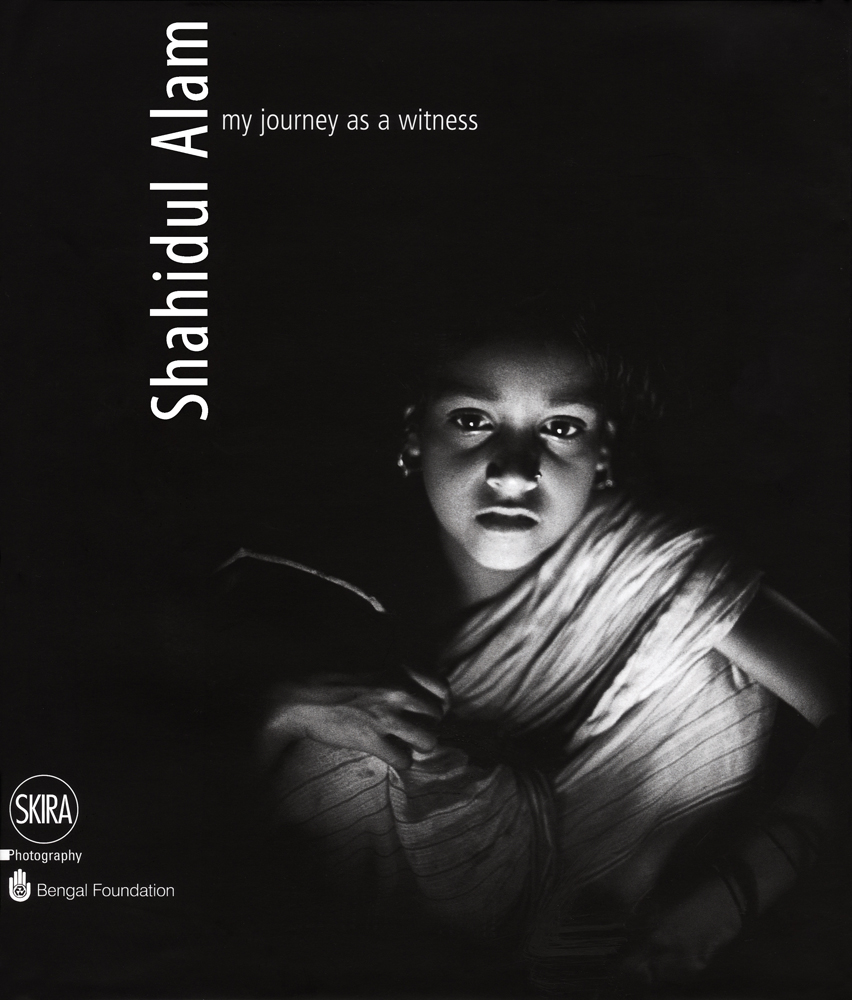

Dr Alam’s aspiration is to teach the pixels to dance. It is a characteristically elegant and evocative phrase in comparison with the generally arid language of the digital lexicon, and it conveys the ambit of his vision and the scope of his knowledge. His Journey is a considerable one. It takes the author from a PhD in chemistry in London to photographer, political activist and educationalist in Bangladesh; it spans the 40 years since the birth of his native country, when he was 16, to its coming of age as an economic and political power amongst Asian nations. Alam has played his part in that growing up. He has challenged oppression and fought for justice and freedom of speech, not infrequently at considerable risk to himself and his partner Rahnuma Ahmed,[i] and he has forged an international reputation.[ii] My Journey as a Witness, published by Skira, Milan, 2011 is a self portrait of an activist who has used photography to chronicle his nation’s anguish.[iii]

This book covers important ground: it describes the story of a significant movement in contemporary reportage photography at a time when the nature and value of photojournalism is uncertain; and it brings into focus the role of the photographer as witness. The camera is held out as a powerful, effective and non-violent weapon in the denunciation of injustice and the fight against oppression, provided that the people behind the lens are of an independent mind and willing to take risks to get and publish their story. The golden age of concerned photojournalism, pioneered by Magnum in the ’40s and ’50s and generally regarded as over by the end of the ’80s, is still alive in Bangladesh.

Pixels, Shahidul observes, can be a vehicle for dreams or a purveyor of lies. He raises legitimate and vital questions about the discipline of photojournalism and its uneasy relationship with truth. A century or more ago Lewis Hine, whose photographs led directly to the introduction of child labour laws in the States, famously remarked that while photographs may not lie, liars may photograph. Photojournalism has always operated in the hinterland between staged work and classic reportage, between images created or commissioned for a prescribed purpose – including some of Hine’s photographs (he would not have been able to take them otherwise) – and those which are visual testament to a moment in time.[iv] This is difficult territory for photographers. Are they to become part of the propaganda machine that commissioned photography frequently amounts to? How do they respond to being embedded with military units? Are they participant, commentator or reporter? If they purport to record injustice should their images be objective by way of evidence,[v] as the word witness suggests (at least to lawyers), or partisan by way of persuasion, so that the photographer becomes the voice of the voiceless?

Alam has always been clear about the role of the photographer. Two years ago he and Susan Meiselas were speaking at the Tate Modern about the depiction of violence in photographic imagery.[vi] A member of the audience asked Shahidul whether his commitment to the cause of humanity was more important to him than his career as a photographer. His response was instant; if the photographic image ceased to be an agent of social change he would drop photography tomorrow. He had discovered, as Philip Jones-Griffiths before him, that ‘with this amazing little brown box round your neck you could change the world’.[vii]

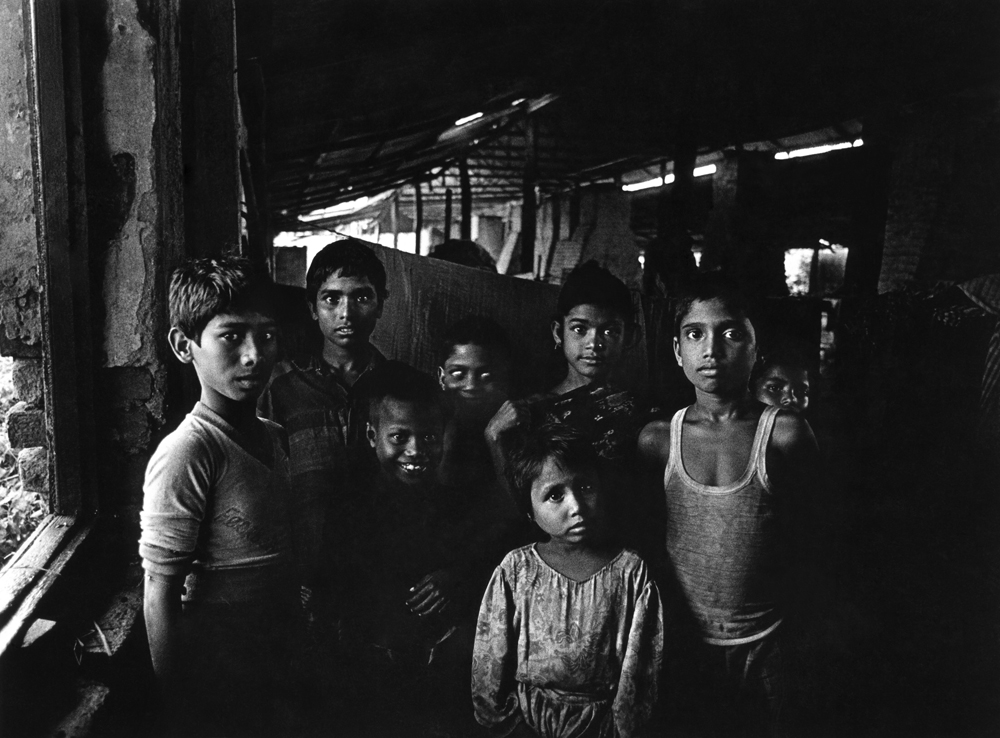

The images in this book are powerful, intimate and uncomfortable; yet they speak collectively of hope. The text lends weight and context. Alam’s account of the blind boy of Gaforgaon who smiled directly into his camera opens our own eyes to questions, but without providing the answers. There are many such personal encounters, often with children. His images of catastrophe, of which Bangladesh has had its fair share, convey hope alongside despair. Flood victims is a graphic image of people whose lives were destroyed by the monsoons that wiped out whole sections of Bangladesh in 1988. The two young girls in the foreground are both smiling.

We see optimism in the face of unimaginable disaster. Alam’s Kashmiri kid is absorbed in his ball-game in the aftermath of the earthquake in 2005, his status as a refugee forgotten by viewers as they are drawn into the boy’s childhood, or perhaps their own. In conveying hope for the future these children call out for our admiration and respect. The sympathy and guilt invoked with depressing frequency in photographs commissioned by western agencies and NGOs are not in Alam’s lexicon.

His images of the labour conditions in Bangladesh exhibit a similar contradiction. A sensitive portrait of a man working in the ship-breaking yards near Chittagong is juxtaposed with an image of jagged sheets of steel borne on the unprotected shoulders of six barefoot men staggering over rough ground. Tenderness stands alongside, and is a constituent part of, the harsh reality of tough brief lives. This is concerned photojournalism with the distinctive Alam stamp, conveying admiration and anger in the same frame.

Crossfire, a collection of images exhibited in Dhaka in March 2010, combines unpalatable facts, legitimate suspicion, and popular outrage. There were eighteen uncaptioned photographs of paddy-fields, street-scenes, a rickshaw, a garment lying on concrete. Only one image, a sheet covering a corpse in a mortuary, suggested that there was more to this collection than met the uninformed eye, for these distinctly ordinary images spoke discreetly but eloquently of terror. Behind each one, linked by Google maps to the victim?s actual family, lies a dark story of sudden death. These ostensibly innocuous images told a story of extra-judicial killings by the State, described by Human Rights Watch as ‘martial law in disguise’. Alam described the exhibition as a quiet metaphor for the screaming truth.

The Government closed Alam’s Drik Picture Agency on the day the show was due to open. His students took the pictures down and hung them in the street. He held a press conference. The show went on,[viii] as did the ensuing Court case: Alam & others v the Government on the right to freedom of speech. Eventually the Government backed down. Shahidul had, in effect, used his photographs to challenge the government?s denials of corruption, collusion in murder and disregard of human rights. The show was not ‘evidence’ per se, there was, as Alam points out, plenty of that in the public domain. It was an explicitly emotional appeal. Alam, to borrow a throw-away remark Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote on a postcard to a fellow-Magnum photographer, was using his camera as a flame-thrower.[ix]

Use of the word ‘witness’ in the book’s title is significant; can a self-confessed activist and flame thrower hold himself out as a witness ‘To wit’ is an old English verb, meaning to see, or to know.[x] It is a multivalent word. Its core meaning is persons who were present when an event occurred, words were spoken or an injustice was perpetrated and who are called upon later to give a truthful report of what they saw or heard. Its primary use in contemporary English is to describe persons who attest to what they know in a Court of Justice. There they are under oath to speak the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

When it comes to photographs the portrayal of truth is complicated. Truth, like a multifaceted diamond which alters with the light, changes in the telling. So does a photograph. Its content and impact change with the height and angle of the camera, the selection of the frame, the photographer’s choice of position, and the exact moment the shutter is released. This is the hinterland between fact and comment so beloved of libel lawyers whose job it is to distinguish fact which has to be proved from comment, or opinion, which does not.[xi] It is in this unallocated space that political awareness and personal agenda shape the truth, the image and the message it conveys. In this context Alam’s claim to being a witness raises my internal eyebrow, perhaps because I am a lawyer by trade and truth supported by neutral evidence is my currency.

Lawyers do not, however, have a monopoly on truth. The word has a wider meaning. Christian literature contains frequent references to those who bear witness for their beliefs, who are prepared to stand firm for, and be loyal to, the beliefs or principles they hold to be true, and if necessary to die for them.[xii] This is the territory which Alam explores, as indeed he should; his very name means ‘Martyr of the World’. This is where his pixels dance; where, as Raghu Rai remarks in his opening preface to this book, Alam sifts through the details of life, revealing a profound understanding of the world around him. He might have added that in that revelation of understanding there is an interpretation informed by political belief and human compassion. Alam is clearly driven by both. His opinions are feisty and are offered with no apology. As Nagel observed, there is no view from nowhere. These images are not mere information. They are intended to provoke a reaction, to rearrange perceptions[xiii].

I have walked and talked with Alam through the streets of Dhaka, conversed with him in tight-fitting rickshaws and waited at traffic-lights in ramshackle cars while he spoke with street-kids. It seems they all know him. They call him Shahidul-bhai, the affectionate form of address given to a revered elder brother. He has given cameras to children like these, taught them to shoot, taken them on as students.

Some of them are now leading international photographers.[xiv] Here is a new generation with a new confidence. They have grown up in a country that was born in one of the bloodiest conflicts of modern times and which is just beginning to emerge from long years of political repression.[xv] These image-makers will have something to say about their sub-continent, and they will, thanks to Alam, have the skill and the courage to bear witness to its truths and shape our perceptions. They will be his legacy.

An understanding of the qualities required of such a witness has never been more important. Amongst them there is the strength to swim against the current, the grace to listen, and a reverence for truth. Alam possesses all these qualities.

When, half a century or more ago, Robert Capa remarked: “It is not easy always to stand aside and be unable to do anything except record the sufferings around one”[xvi] he raised a different but related question: where does the boundary lie between the witness who stands aside from the fray and the activist who fights in the front line? Perhaps Alam, with his command of words, skill with the camera and charismatic energy, can explore this issue in his next book.

[i] Rahnuma Ahmed founded and chairs the first department of Anthropology in Bangladesh. The author of several books, she is a regular columnist on women’s issues and contemporary politics. Along with Shahidul Alam, she has been attacked, arrested and over the years received anonymous death threats.

[ii] Alam set up the Drik Picture Library and News Agency, and Pathshala, the South Asian Institute of Photography. He is Director of Chobi Mela the festival of photography in Asia. He has exhibited in MOMA New York, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Arts, the Royal Albert Hall, Georges Pompidou and the National Art Gallery in Kuala Lumpur. He has chaired the World Press Photo international jury, is an honorary fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, a board member of the National Geographic Society and the Eugene Smith Foundation. He is also Visiting Professor of Photography at the University of Sunderland and has lectured at Harvard, Stanford, Oxford and Cambridge amongst other universities.

[iii] Published by Skira, and edited by Rosa Maria Falvo, My Journey as a Witness (2011) was selected as one of the ?Best Photo Books of 2011? by American Photo.

[iv] The driving force behind the invention of photography (1839) was to produce accurate documentation of scientific data. Forty three years later Darwin acknowledged in his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) that the photographic illustrations were ?faithful copies, far superior to any drawing?.

[v] Giles Peress’ photographs of the Bloody Sunday riots in Northern Ireland in 1972 are a good example of such photographs. Nearly 40 years after they were taken his images and particularly his contact sheets which showed the sequence of events – were critically important evidence in The Saville Commission in 2010. As he put it – “I have these pictures of this guy alive and then dead; the images clearly show he has no weapons”. See Magnum Contacts Thames & Hudson 2011. It is worth noting in this context that digital images, edited and improved as they always are, would have been of limited if any value.

[vi] Meiselas is a member of Magnum. Her book Nicaragua June 1978-July 1979 was re-released in 2009. They were addressing issues raised by her images of Nicaragua then on show in the Tate Modern. I was with them on the platform and spoke on censorship.

[vii] 1936 – 2009. Magnum from 1966, President for 5 years in the ’80s. His book Vietnam Inc crystallized public opinion on the Vietnam War.

[viii] Reported on the front page of the British Journal of Photography 5 May 2010

[ix] Cartier-Bresson sent a postcard to Patrick Zachmann, after the latter had been shot by the police in 1990 outside Mandela’s prison, on which he wrote: ‘just think of your camera as a flame-thrower [?] a lot more effective [than bullets]’. The photograph Zachmann took at the exact moment he was shot has been widely used to illustrate the fight for press freedom.

[x] Wisdom comes from the same (Latin) root.

[xi] Defamation Act 1996, UK

[xii] The word for witness in ancient Greek is martyr.

[xiii] Alam is by no means alone in this approach, though his objective might be different. Leonard Freed, 1929-2006, Magnum from 1972, had this to say: ‘I don’t make informational photographs. I am not a journalist. I am an author. I am not interested in facts. I want to show atmosphere’. He was rated by the then director of photography at MOMA (1966) as one of the 3 best young photographers he knew. Last year his widow recalled that he ‘gave us a front seat to life in all the various forms that it must take’. There are few finer epitaphs for a photographer.

[xiv] Munem Wasif for example. His Saltwater Tears, contains powerful images of the rising salinity levels in the Sunderbans. Prix Pictet exhibition at the Mall Galleries, London in 2009.

[xv] When Bangladesh was created in 1971 it had 10 million refugees on its hands, no money, no schools and no government structure. The intellectual elite had been virtually eliminated by the departing Pakistan army. Amongst the few survivors were Alam and his parents. Henry Kissinger somewhat discouragingly once described this new country as an international basket case. Not any more.

[xvi] Magnum Magnum, Thames & Hudson 2009, p. 264.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.