Image and text contributed by Sreenivasan Jain, Mumbai

Some text is paraphrased from a recent Book ? Civil Disobedience, Sreenivasan?s father Late. Shri LC Jain, noted economist and Gandhian.

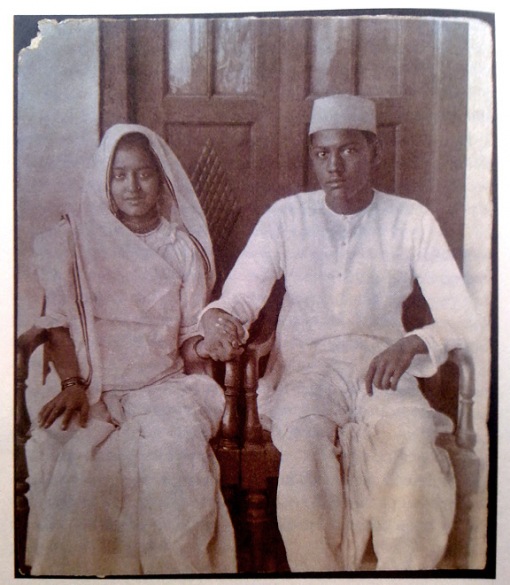

This image was photographed in Delhi, shortly after my Paternal grandparents Chameli and Phool Chand, got married. She was 14 and he was 16. It was unusual for couples in our family to be photographed, especially holding hands, which turned out to be an indication of the unconventional direction their lives would take. They were both Gandhians and Freedom fighters.

The prestigious Chameli Devi Jain award for Journalists was named after my grandmother . The only visible reminder of her brush with radical politics of the freedom movement was the milky cornea in her right eye, the result of an infection picked up in Lahore Jail where she had spent 4 months in 1943. Otherwise, she was Ammaji: gentle, almost luminous in her white saris, regular with her samaik (Jain prayer), someone who would take great pleasure, on our Sunday visits, to feed us dal chawal (rice and lentils) mixed with her own hands.

My grandmother grew up in a village called Bahadarpur in Alwar, about 4 hours south of Delhi, in a deeply conservative Jain family. The family was locally influential; they were traders in cotton turbans, woven by local Muslim weavers and sold in Indore, Madhya Pradesh. They also were moneylenders. As with much of rural Rajasthan, the women were in purdah. Within two years of their marriage, their first child, my father, LC Jain was born.

Ammaji moved with my grandfather into the family home in the teeming bylanes of Dariba in Chandni Chowk. But he had developed a growing interest in Gandhi and the nationalist movement and soon broke away from the family business to join the Delhi Congress. In 1929, soon after the call for Poorn Swaraj at the Lahore session, he was arrested for the first time.

My grandfather?s stint in jail exposed him to even more radical politics. Along with his Congress membership, he also became part of the revolutionary Hindustan Socialist Republian Association which counted Bhagat Singh and Chandrashekhar Azad as amongst its members. (Azad, in an interview, acknowledged that he received his first revolver from my grandfather). He also became a reporter for the nationalist newspaper at the time, Vir Arjun, whose editor he had met in jail.

In 1932, Gandhi called for a major nationwide satyagraha against foreign goods. It was also the year a bomb was thrown at Lord Lothian, an act in which my grandfather played a role. When he told my grandmother that he was going to jail, she said this time she would go to prison first, by taking part in the swadeshi satyagraha. The household was stunned. Ammaji?s life had revolved around ritual, the kitchen and ghoonghat. Her decision led to the following heated exchange; witnessed by my father, age 7:

Babaji: ?You don?t know anything about jail.?

Ammaji: ?Nor did you when you were first arrested.?

Babaji: ?Who will look after the children ??

Ammaji: ?You will.?

Sensing that things were getting out of hand, my great grandmother, Badi Ammaji locked both of them into a room. But my grandfather apparently fashioned an escape from the window using knotted dhotis and Ammaji, head uncovered, marched with other women pouring out of their homes towards the main bazaar. The crowd had swelled into hundreds. There were cries of ?Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai?. As they began to move around picketing shops selling foreign goods, they were arrested, taken to Delhi Jail, and charged with 4 and half months of rigorous imprisonment.

Her arrest, not surprisingly, outraged the family in Alwar. Umrao Singhji, Ammaji?s father, came to Delhi and had a big argument with my great grandfather, accusing the in-laws of ?ruining our princess?. But Ammaji found an ally in her in-laws, who refused to pay her bail out of respect for her satyagraha. Umrao Singhji then tried to talk his daughter out of it when she was being transferred to Lahore Jail. ?Chameli, apologise, ask for pardon.? But Ammaji asked him not to worry. ?Bolo Bharat Mata ki Jai?, she said, as she was being led away in a rickshaw along with the other prisoners. ?Bharat Mata ki Jai?, responded her father.

She returned from Lahore 4 months later, a minor heroine. But there was also loss. Lakshmi, her daughter, 5 years old, fell from the balcony of the house and died when she was in Lahore jail. And there was the milky cornea ? the loss of an eye. But her world had somewhat widened. She wore her ghoonghat a few inches higher. She gave her Rajasthani ghaghra choli away, and wore only handspun. She spun on the charkha. She would attend meetings with other women on matters of community reform, like widow remarriage and also became more involved in the activities of the local sthanak, the Jain community?s prayer and meditation hall. She had, as it turns out, quietly fashioned her own blend of Jain renunciation and Gandhian abstinence.

In the years that followed, my grandfather retained his engagement with the freedom struggle. He would often go to sit in the family?s property agency in Model Town, but his real passion, which consumed most of his last 30 years was compiling a massive index of freedom fighters, a staggering 11 volume chronicle of the stories of countless ordinary men and women, who took part in protests, bomb conspiracies, went to jail, lived and died. For my grandmother, it was a gradual return to a more conventional domesticity.

But, that single action that morning in 1932 had opened up a world: a young woman from a deeply conservative family, who became the first Jain woman in her neighbourhood to go to jail, who was named on the day of her arrest in the Hindustan Times with all the other satyagrahis, who would return home to other freedoms, even if minor, like a ghoonghat that could be worn a few inches back.

And for that, she would, one day, have an award named after her.

Presented by Anusha S Yadav at the CHHAYA International Conference on Photography of India

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.