‘REPEAT a lie often enough and it becomes the truth’, is a law of propaganda often attributed to the Nazi Joseph Goebbels. The Bangladesh government seems to have studied Goebbels’ book well. The lies generally come in the form of denials. ‘No, we have not been involved in “crossfire” and “disappearances”.’ ‘There is no political motive.’ ‘No one will be spared.’ ‘The elections were fair.’ ‘The judiciary is independent,’ the list goes on. The lies are repeated ad nauseam in political rallies, in talk shows, in press briefings and through social media trolls.

‘We do not condone any such incident and will bring the responsible officials to justice’ said the foreign minister Dipu Moni at the Universal Periodic Review of Bangladesh at the Human Rights Council in Geneva on February 4, 2009 in response to accusations that the government was involved in ‘crossfire,’ a Bangladeshi euphemism for extra-judicial killings. She added that the government would show ‘zero tolerance’ to extra-judicial killings, or torture and death in custody. Indeed, doing so was part of the election campaign for the Bangladesh Awami League when they were in the opposition. As often happens however, once elected, their position changed, and ‘crossfire’ has become so integral to the Bangladeshi lingo that MPs now use the term in parliament, ‘You are allowing crossfire as part of a fight against drugs. Then why aren’t you doing the same in case of rape?’

Following a non-participatory election in 2014 and a blatantly rigged one in 2018, the number of both ‘crossfire’ deaths and ‘disappearances’ have sharply increased.

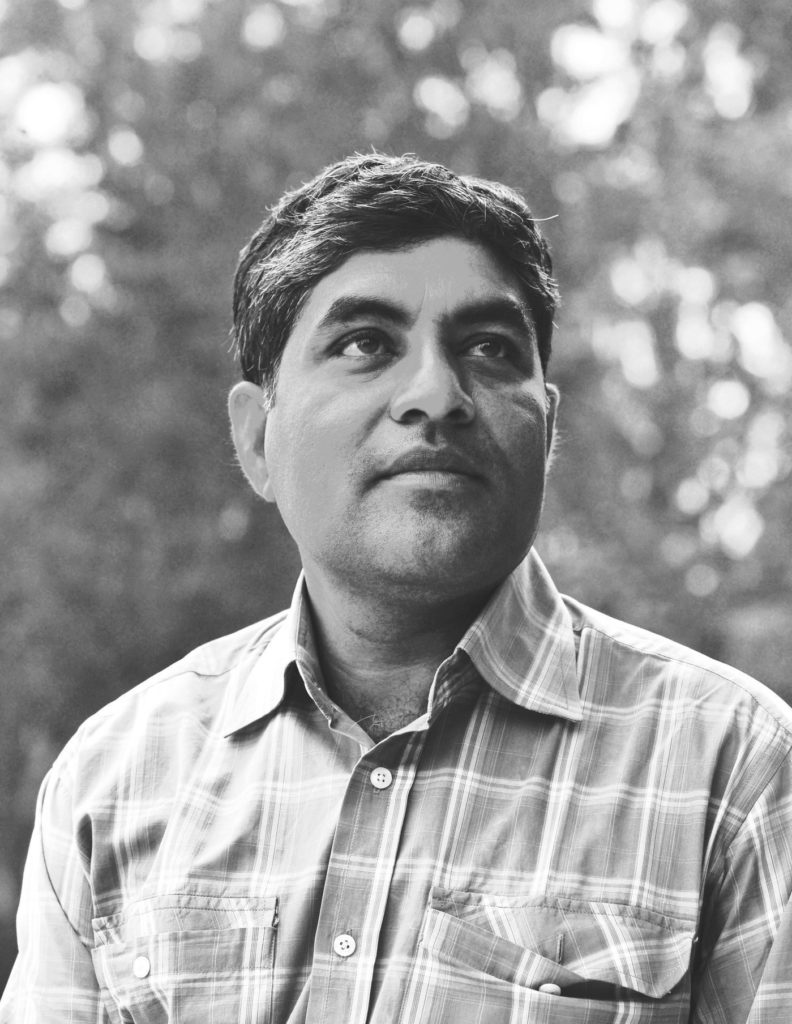

On March 10, 2020, the Bangladesh police registered a case against photojournalist Shafiqul Islam Kajol and 31 others under the country’s draconian Digital Security Act for publishing ‘false, offensive and defamatory’ information on Facebook. He has not been seen since. Kajol had been posting stories about members of the ruling party who had been involved in sex scandals. His family fear that he has been ‘disappeared’ because of his reporting. The case had been initiated by an MP of the ruling party. The police have denied having him in custody, but initially refused to accept the complaint by the family, and accepted the general diary only after the family obtained a court order, instructing them to do so. Their reluctance to investigate the matter, despite being provided CCTV footage clearly identifying people seen to be tampering with Kajol’s motorbike, fits with the pattern of enforced disappearances the country has become known for.

Kajol, was clearly a dissenter, but he was not an ordinary dissenter. By all accounts he was well in with high ups in the ruling party. Present at most AL rallies, his initiation rites of passage, which included being attacked with a boti (sharp kitchen utensil used for cutting fish) and having his skull cracked twice covering their rallies, should surely have held him in good stead.

He had been involved in student politics even before he got close to the AL. Then he had been a committed member of Chhatra Moitree, a progressive students organisation. He later played a role in the resistance to the autocratic General Ershad. I wonder how he felt when the same General Ershad later became the AL prime minister’s special envoy. Such is realpolitik.

Starting as a photojournalist in the New Age, he had also been a contributor to DrikNews. He moved on to the newspapers Samakal and Jai Jai Din and until recently in Bonik Barta. He tried on his own too, and had been one of the early initiators of online newspapers in Bangladesh through the startup Kaler Chaka, eventually starting his own newspaper Dainik Pokkhokal, where he was working both as editor and photojournalist.

He loved taking pictures, news photographer’s staple diet of handshakes and mugshots didn’t interest him and he shunned seminars and events, photographing instead the downtrodden whom he gravitated towards. He responded to people’s pain, and while the subjects that make up the bread and butter of photojournalists, disasters, rag pickers, children in factories, acid victims and disadvantaged people were also the subjects he gravitated towards, he had a natural empathy, and to him they were more than mere ‘subjects’. He befriended a group of biranganas (rape victims of the war of liberation) who were hungry and neglected, producing a photo essay that highlighted their plight. When one died, he collected money adding his own, to arrange for her funeral. His own family never had much money, but he found ways to raise money for the women. At a time when Nilima Ibrahim’s book Ami Birangona Bolchi (I am the War Heroine speaking) was one of the few publications on birangonas, Kajol produced a documentary and a book on them. Both productions were supported by his powerful friends, but when his journalism took him too close, patronage evaporated.

In a public letter to his father, his son Polok writes, ‘Will they let you come back?’

That’s the question that torments the families of the disappeared.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.