Rahnuma Ahmed

Amar jiboner sreshtho shomoita dilam. Amar joubon amake ke phirie debe?

(I gave the best years of my life. Who will give me back my youth?)

A Bangladeshi migrant. Paris, 2002.

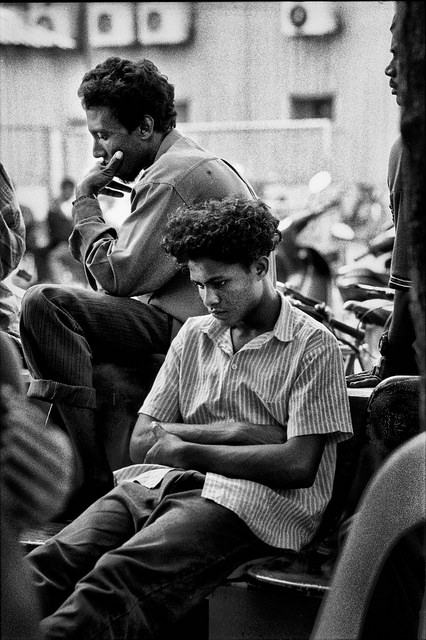

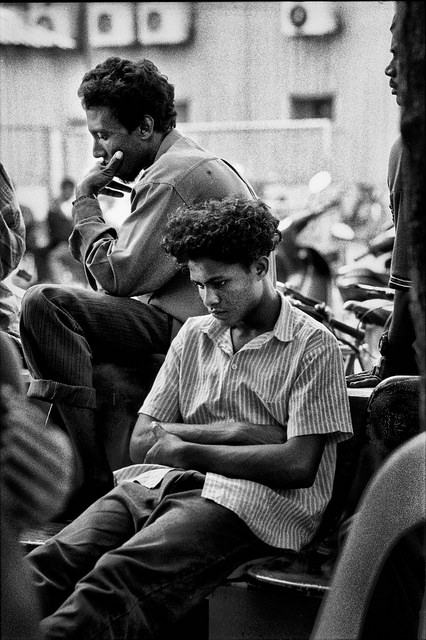

[caption id="attachment_18764" align="aligncenter" width="426"]

Bangladeshi workers resting in between shifts in Maldives. ? Shahidul Alam / Drik / Majority World[/caption]

?The best years?. Being treated like an animal

?I slept many nights beside the road and spent many days without food. It was a painful life.

I could not explain that life,? these are the words of a Bangladeshi migrant worker who had gone to Saudi Arabia. He was speaking to Human Rights Watch researchers who spoke to other Bangladeshi migrants, also to migrants from India and the Philippines (Bad Dreams: Exploitation and Abuse of Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia, 2004).

But not all migrant workers were abused, not all were exploited to their bones. Somewhere else, I read about Manzur Ali who first went to Saudi Arabia in 1982, and later again in 1999. His first employment is the stuff that migrants? dreams are made of. His Saudi employer bore the entire cost of his travels. He worked in a construction firm as a carpenter. His monthly earnings, including overtime, reached twelve to thirteen hundred riyals, in our currency, 21,000 to 23,000 taka. Food, housing and medical facilities were provided; also, a fifty-day annual leave. Manzur worked for three years, returned home and started a business. His second visit was disastrous. He had to pay a recruiting agency 80,000 taka. His monthly wages were not the promised 9,500 riyal, but only 650. He had to work three times harder than before, if he failed, he was physically tortured. Since his employer did not give him his resident permit, he was not allowed to go outside the firm premises. Eleven months later he escaped to Riyadh, and to a long spell of illegal work. Caught by the police, he was arrested and deported to Bangladesh six years later.

Contrary to common expectations, migrants who enter legally and comply with government regulations can also be cheated, overworked, underpaid, or not paid at all. Bangladeshi workers repairing underground water pipes in Tabuk municipality, Saudi Arabia, told HRW researchers that they were forced to work ten to twelve hours a day, sometimes throughout the night and without any overtime pay. They were not paid salaries for the first two months, and had to borrow money from other Bangladeshis to buy food. Another migrant, who worked as a butcher in Dammam, was forced to leave the kingdom by his employer with six months of his salary unpaid.

Women migrant workers spoke of torturous working conditions. Hundreds of low-paid Asian women, who worked as cleaners in Jeddah hospitals, had to work twelve-hour days, without any food or break. After work, they were confined to locked dormitories. Skilled seamstresses from the Philippines, who worked twelve-hour days, spoke of not being permitted to leave their workplace, of being forbidden to speak more than a few words to customers and the Saudi owners. A Filipina, who worked for a family in Dammam, was raped by her male employer. She spoke of her trauma, and how she was constantly on the lookout for the front gate to be unguarded, so that she could escape.

But not only cruel employers and unscrupulous middlemen are to be blamed. Flawed immigration policies and gaps in labour laws expose migrants to trafficking, forced labour and other terrible abuses. A twenty-three-year-old Indian tailor, while in police custody, was beaten for two days. On the third day, his interrogators gave him two pages handwritten in Arabic. He was to sign his name three times on each page. He said, ?I was so afraid that I did not dare ask what the papers were, or what was written on them.?

What words do South and East Asian migrant workers use to describe their migrant situation? I kept coming across metaphors of slavery, of being treated like animals. By their employers, by recruiting agents, and also by embassy officials. A Bangladeshi migrant working in a textile factory in Jordan detailed the physical and verbal abuse doled out by his employer: ?severe beating, verbal insults, threats of deportation and forcing them to sign blank documents?. He said, five people, including two women, had been beaten over the past two days, and added, ?They want us to work like slaves.? Widyaningsih, a 35-year-old Indonesian woman, a would-be migrant to Malaysia, described the conditions she had faced while being recruited in Indonesia: The broker brought me to the training centre in Tanjung Pinang by ship?. they deducted my full wages for four-and-a-half months [to repay what they said were up-front costs]?. I had to spend two months at the training centre. We were never allowed outside, there was a very high gate and it was always locked. They treated us poorly, always calling us names like ?dog?. And a Bangladeshi woman, a migrant worker who had recently returned from the Middle East, said, Bangladeshi embassy officials ignore us, they don?t even recognise our difficulties, ?They treat us like animals.?

Objectifying migrant workers

At home, in circles of power, migration is discussed in two basic ways: in a language of absence or ?lack?, and in the language of remittances. Never in the language of suffering, or pain, or dreams crushed, or accountability.

Men and women who go abroad as migrant workers are described in terms of what they lack, they lack education, they lack skills (at most, they are described as ?semi?-skilled). There are deeper connotations, they seem to be lacking culture, lacking the best of what the nation has to offer. They have only their labour, and that too,

menial. Their presence, and what they bring back as personal belongings (blankets, TVs, camera, mobile phones, photo frames), packed tightly in mounds of carefully sewn luggage often give rise to patronising looks of their better-off compatriots at airports.

But what migrant workers send back are not sources of embarrassment.

Remittances belong to the nation. I watch experts speak at seminars and conferences with a self-congratulatory air. Migrant remittances, they say, are the ?major source of national revenue?, they enhance ?national economic growth?, Bangladesh is ?a notable exporter of manpower?. I see experts look prophetically into the future, ?From its current position Bangladesh has to increase its remittance income by 25 per cent year on year to generate remittances income of approximately US$ 30 billion in 2015.?

Sometimes, I hear them sound alarm bells. We get told, ?The rise in remittance and overseas employment is on the verge of witnessing a downward trend?, ?The government target of reaching fresh overseas employments to nine lakh this year is also likely to fall flat?, ?We can?t feel the blow of the bans or cut in overseas employment immediately, but after two to three years remittance will definitely dry up if no major changes take place?.

Migrant men and women are objects to

the nation?s goals

. They are never spoken of as heroes.

Family ties

I sit and chat with Shireen Huq, an old friend, whose mother, poet Jaheda Khanum, passed away this March. I prod her gently,

what was it khala used to say about class differences between migrant families and our families?

Well, says Shireen, she would look at her Dhanmondi neighbours, at their expatriate sons and daughters, those who are well-educated, in professions, who live abroad and insist that the family home in Dhanmondi be turned over to developers, because they need the money there. Actually someone we know quite well, he has never sent anything, in twenty long years, not a single cent. Not for his mother, or his brother, or his sister. But as I was saying, someone amma knew well, immediately after she died her children insisted that the land be sold, they need the dollars abroad. But another neighbour, her children exerted tremendous pressure on her, but can you imagine, she was still living, they said to her, go and live in a small flat. We need the dollars now. I mean, they didn?t wait, they couldn?t wait for her to pass away. And amma, she would compare them with young migrant men she met in New York, she went there once, she would say, they turn their blood into water to send money to their families in Bangladesh. And then she would say, people of our class are paying for their economic and social mobility.

As I write, I grieve for Bahraini fashion designer Sana Al Jalahma, murdered in August 2006, and Mizan Noor Al Rahman Ayoub Mia, who worked for the family, and was accused and convicted of the murder. Mizan was executed by a firing squad early June 4, 2008.

Two lives lost. Lives, and losses, that are difficult

to explain.

First published in

New Age on Monday 9th June 2008

Film on migration:

In Search of the shade of the Banyan Tree

Website on migration:

Migrant Soul

Bangladeshi workers resting in between shifts in Maldives. ? Shahidul Alam / Drik / Majority World[/caption]

Bangladeshi workers resting in between shifts in Maldives. ? Shahidul Alam / Drik / Majority World[/caption]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.