rahnuma ahmed

It was a peaceful procession.

We had gathered under the aegis of the National Committee to Protect Oil, Gas, Mineral Resources, Power and Ports, outside the National Press Club in Dhaka, on October 19, 2016. After a brief rally, where speakers described the harm that the Rampal coal power plant would cause the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest straddling both sides of the Bangladesh-India border, we formed a procession, raised slogans and proceeded toward the Indian High Commission in Gulshan to deliver an open letter for the Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.

Since India is the major partner in building the Maitree Super Thermal Power Project, i.e., the Rampal coal power plant, the National Committee’s open letter called on the Indian prime minister to scrap the project.

It’s not only us. Forty-one Indian people’s movements, green and civil rights organisations have called on Narendra Modi to scrap the the project. So has the Unesco and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). A Unesco statement recommended the ‘Rampal power plant project be cancelled and relocated to a more suitable location’ as it could damage the world heritage site, home to 450 Royal Bengal tigers, expose downriver forests to pollution and acid rain, threaten the breeding grounds of Ganges and Irrawaddy river dolphins, far worsen the already liminal ecosystem which is being threatened by rising sea levels (The Guardian, October 18, 2016). Three large French banks, including BNP Paribas, a sponsor of the Paris climate summit in 2015, have refused to invest, while two Norwegian pension funds have withdrawn their investment.

Prime minister Sheikh Hasina, for reasons unknown, insists on going ahead with the project. Her fawning supporters, for reasons that are obvious (a slice of the pie?), repeatedly assure all and sundry, she knows what is best for the nation, insisting at the same time that the Awami League is commited to democracy. Some of them, cabinet ministers included, spew utter nonsense. Anwar Hossain Manju, environment and forests minister, when asked about the declining number of tigers in Bangladesh, replied flippantly, they ‘have gone on a holiday to West Bengal.’

When we reached the Malibagh rail crossing, our procession was forced to split into small groups, largely because of the under-construction flyover; iron rods, bags of cement and other building material heaped high made us slow down, we picked our way gingerly over little puddles of rainwater, squatting construction workers, rikshas and honking cars, only to look up and find a large contingent of riot police facing us.

We attempted to break the police barricade but were attacked from both Malibagh and Mouchak ends by tear gas and blasts of water. I dived into a shop just as the shutters were being hastily drawn down, catching a fleeting glimpse of a young protester, badly injured, being carried away by fellow demonstrators. I learnt later that he had to be hospitalised, like many others.

Dissent is not tolerated by the Awami League government.

Nearly three hours later, Dr Mohammad Tanzimuddin Khan and I went to a hospital in Maghbazar, to see the injured (after having delivered the open letter to the Indian High Commission; see, ‘Go back NTPC, get out India,’ New Age, Independence Day Supplement, March 26, 2017). One of the injured, a student belonging to the Chatra Federation, was suffering from breathing difficulties. He had inhaled quite a bit of gas, and complained of nausea, tightness in his chest. Others had similar complaints. I felt somewhat perplexed. Tear gas earlier, would make one’s eyes teary and watery, why the breathing difficulties? Was this a new kind of tear gas? Who had manufactured it and where? What agents (chemicals) had been used?

Mehedi Hasan, a young activist (gym instructor and violinist), Tanzim Khan and I decided to return to Malibagh and search for tear gas canisters. It was late afternoon, the ‘crime scene’ had been swept clean, tragically, by street children, who had carted away all battleground artefacts to a nearby seller of tin cans and broken glass bottles (their precious earnings contribute to family meals). Construction sardars, workers, car drivers idling around, stray passersby joined in our search, finally, we found an empty tear gas canister, tucked away under heaps of rods and wooden planks.

Strangely, it was as clean as a whistle, no seal, no number (see Photo 1).

For the next forty-eight hours or so, we conducted extensive searches on the internet, from our respective homes, passing information uncovered to each other.

On November 26, 2017, at the ‘Dhaka chalo‘ mass rally, leaders of the National Committee announced a half-day hartal in Dhaka city (6 am-12 pm), to be held on January 26, 2017 if the Rampal project had not been scrapped.

A friend and I decided to join the picketers at Shahbagh. We had barely reached the row of shops lining the road leading to the roundabout, it wasn’t 7 am yet when we heard shots, saw fleeing office-goers run toward us, chased by clouds of smoke. This early? They must be mad, I thought to myself (it wasn’t only me, the police were roundly condemned later, in TV talk shows as well, for the deployment of excessive violence).

During a lull we crossed over, as we left the roundabout behind, we saw a cordon of riot policemen and women, armed and helmeted, they stood close to the Shahbagh police station, almost under the shade of a water cannon truck, towering above them.

We joined the demonstrators grouped outside the Arts Institute, some of them hunched up over small fires, lit to reduce the sting of the tear gas. After many rounds had been fired, after some demonstrators had been rushed away to the Dhaka Medical College and Hospital?one of them hit by a tear shell in the leg, it had torn away a bit of flesh?I saw reporters and TV camerapersons close to the thana, rush up and huddle around someone. I went and joined the huddle. A senior police officer was speaking of how the police had been forced to fire rounds of tear gas, the demonstrators were violent, they had hurled bricks and stones, there was a public hospital nearby (BSMMU), portecting the sanctity of the hospital was their duty. Firing countless tear gas shells near a public hospital to protect members of the public? I butted in and asked him, where has the tear gas been imported from, which country? I had to repeat my question before he replied, jekhan theke hoy. Bolte parbo na, bolbo keno? (from wherever they are. I can’t say. Why should I?) He pivoted on his heels and walked away. The huddle dissolved.

I hung around, watched a policeman diligently pick up empty tear gas canisters, store them in a bag slung over his shoulder (official records? see Photo 2). I walked over, began chatting with some of the policemen, one of them said, ‘You people have no objections to the Chinese,’ my question, whaa, who said so? was soon drowned by, ‘And where were you when the Rohingyas were driven out?’ So, is that how they are brainwashed into firing at us. And who, I wondered, dishes out these fabrications? Who are the puppet masters?

I was nearly convinced that the tear gas fired at us was imported from South Korea after I came across Ahmad Ali’s interview, he’s a Bahraini law student, a member of the Bahrain Watch Organization, and a supporter of the pro-demcracy protests in Bahrain. Ali says, ‘unmarked tear gas canisters’ (Photo 1) were used by security forces in Bahrain during the 2011 uprising. These are ‘visually identical’ to those manufactured by the South Korean firm Daekwang, exported by CNO Tech. Their suspicions were confirmed when Bahrain Watch got hold of a confidential tender document of the Bahrain Ministry of Interior, seeking a large shipment of tear gas (1.6 million tear gas canisters) from South Korea. Bahrain Watch launched a ‘Stop the Shipment’ campaign, with the assistance of Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Campaign Against the Arms Trade, and MENA Solidarity Network; they launched an email campaign which elicited 17,000 letters; they contacted the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions; held a joint seminar with Korean civic groups; Bahraini activists went and addressed the Korean National Assembly (Bahrain Mirror, October 21, 2013).

Bahrain Watch says it launched the campaign to provide Bahrainis the opportunity of expressing their discontent at ‘tear gas being used as a tool of oppression, as a tool for the prevention of self-determination, as a tool of killing and targeting men, women and children in their homes.’ The campaign, they say, also helps to ‘notify citizens of…exporting countries [South Korea, about] how their home grown products are being used to kill freedoms elsewhere.’

Bahrain Watch says, tear gas, including that imported from South Korea, has been ‘misused by riot police …and has been directly linked to the deaths of 39 people.’ Fifteen-year old Sayed Hashem Sayed Saeed was ‘shot in the face with a tear gas canister on New Year’s Eve.’ He died of excessive bleeding.

South Korea’s Defence Acquisition Program Administration (DAPA) suspended tear gas exports to Bahrain in January 2014 because of the ‘unstable politics in the country [Bahrain], people’s death due to tear gas and complaints from human rights groups.’

Turkish activists have initiated a similar campaign about the misuse of tear gas in Turkey.

Arms exports have led to the rapid expansion of the South Korean defence industry (tear gas, firearms, grenades, fighter jets, submarines), euphemistically referred to as the ‘New Korean Wave.’ Earnings from defence increased more than 13 times in 7 years, it rose from 250 million dollars in 2006 to 3.4 billion dollars in 2013. Korean activists have not failed to remind their government that the country is a signatory to the Arms Trade Treaty, and that South Korea is equally responsible if its arms are used in human rights violations elsewhere.

I came across two pieces later which confirmed our suspicion. Tae-jun Kung writes in the Diplomat, South Korea exported ‘about 180,000 shells…to Bangladesh, where there have been ongoing protests by labor workers seeking better working conditions’ (October 17, 2014). Dahee Kim writes in the Human Rights Monitor South Korea, Bangladesh imported approximately 190,000 tear gas canisters from South Korea as it was ‘suppressing frequent demonstrations’ (April 1, 2015). An unelected government, without a popular mandate, dependent on the security forces to stay in power, a fact the latter know only too well.

It is ironic that the South Korean police had deployed 351,000 canisters and grenades during the anti-government demonstrations of 10-27 June 1987, i.e., more than 20,000 were fired every day to quell protests in a country which now manufactures products used to quell democracy movements elsewhere.

It is also ironic that a study of South Korea’s development and what Bangladesh can learn from it, lists major imported products from Korea as being ‘machineries, iron steel, telephones, automobiles, machineries for air-conditioning system, knitting machines, electroplates.’ No mention of tear gas. For fear that it will complicate the ‘development’ story? (Khondaker Golam Moazzem and Meherun Nesa, ‘Dialogue on Korean Development Experience: Lessons For Bangladesh,’ Centre for Policy Dialogue, 2014).

How harmful is tear gas? It causes ‘widespread suffering’ among innocent civilians, it may cause ‘serious and painful acute illnesses’ with ‘permanent impairment,’ ‘aggravate or cause long term lung disease,’ say the Boston-based Physicians for Human Rights. Using it is ‘tantamount to [conducting] chemical warfare against civilians’ (Washington Post, July 23, 1987).

In the context of the killings at Ferguson, United States, and the Black Lives Matter movement, a spate of articles have been written about the harm caused by tear gas. Meredith Melnick writes, tear gas is a chemical weapon, while the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993 banned its use in war, its use as ‘a tool of riot control’ is not prohibited as international treaties are not applicable to domestic situations (Huffington Post, August 14, 2014).

The authors of a recent scientific paper decry the lack of epidemiological research on the effects of tear gas despite its increasing use worldwide (in countries as diverse as Turkey, the US, Hong Kong, Greece, Egypt, Brazil, Bahrain), and also, in densely populated cities. Concerned about its impact on public health, the authors cite case studies and epidemiological studies which reveal that ‘tear gas agents can cause lung, cutaneous, and ocular injuries, with individuals affected by chronic morbidities at high risk for complications.’ It can result in instant irritation to the eyes, nose, mouth, skin, and respiratory tract. High concentrations of CS or OC gas can cause ‘severe respiratory symptoms,’ including throat pain, cough, bronchitis, sinusitis etc. Deployed at a close range, tear gas can cause conjunctival tearing, and lead to ocular complications such as glaucoma, cataract. ‘Unusually severe skin reactions’ have been reported, write the authors, as have gastrointestinal complaints such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea. ‘[E]xposure to high concentrations of tear gas or exposure in enclosed spaces or for extended periods of time’ may lead to death. (‘Tear gas: an epidemiological and mechanistic reassessment,’ Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, No. 1378, 2016).

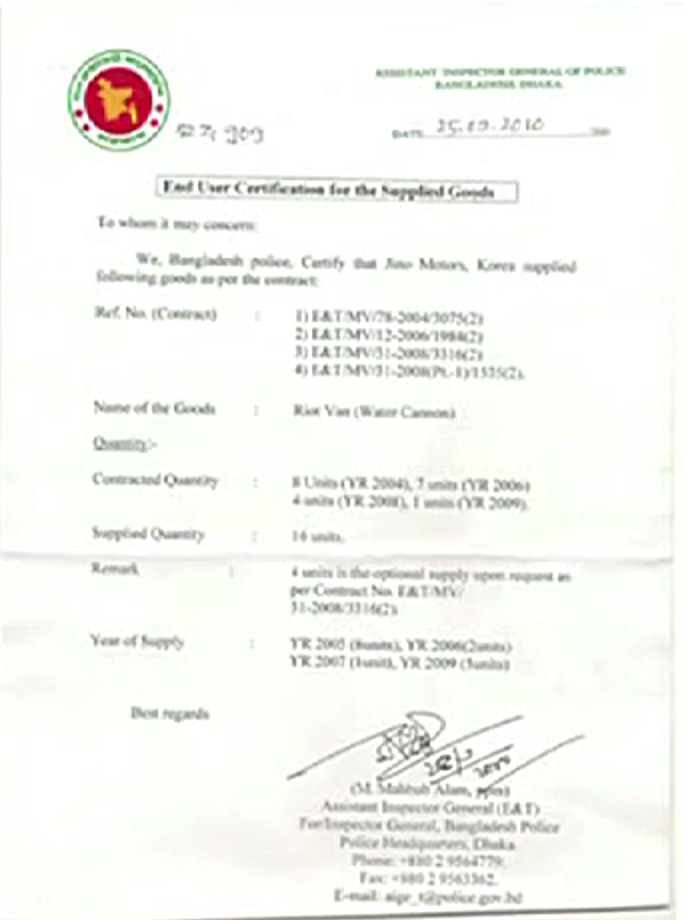

The water cannon trucks used to quell anti-Rampal protests are also imported from South Korea. Daewoo vehicles seem to have have given way to ones manufactured by Jino Motors, which prides itself on giving the customer exactly what it wants. In a self-promotional video available on youtube, ‘Riot Control, Water Cannon Vehicles-by Jino Motors, Company Introduction,’ the company lists Bangladesh as a purchaser, this is accompanied by a shot of the End User Certification for the Supplied Goods, dated 25.10.2010, signed by M Mahbub Alam, Assistant Inspector General, E&T (6:31/7:32; see Photo 3). The number of water cannons purchased is indistinct, possibly fourteen.

Recently, the South Korean ambassador to Bangladesh Ahn Seong Doo gifted a grand piano to the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. It was graciously received by Shilpakala’s director general Liaqat Ali Lucky at a programme attended by the cultural affairs minister Asaduzzaman Noor, cultural affairs secretary Aktari Mamtaz, and Youngone Corporation chairman Ki-Hak Sung. Interestingly, Youngone owns garment factories in the Korean EPZ in Chittagong (‘about 180,000 shells…to Bangladesh, where there have been ongoing protests by labor workers seeking better working conditions’). Will the sound of the South Korean piano drown out the voices of Bangladeshi workers demanding decent wages, will it drown out the sound of South Korean tear gas being fired by the Bangladesh police?

? SaveSundarbans/SaveBangladesh facebook page.

That the South Korean water cannon truck refused to intimidate anti-Rampal protestors was evident at Shahbagh when longtime activist Mizanur Rahman protested against police violence by leaping head on, holding on to the truck’s iron casing (Photo 4). I salute his courage. Long live resistance!

May solidarities be forged between the peoples of South Korea and Bangladesh to unite in the fight against profiting from repression. To unite in the struggle for saving forests and trees and tigers and peoples from state repression.

Published in New Age, 09 April 2017

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.