by rahnuma ahmed

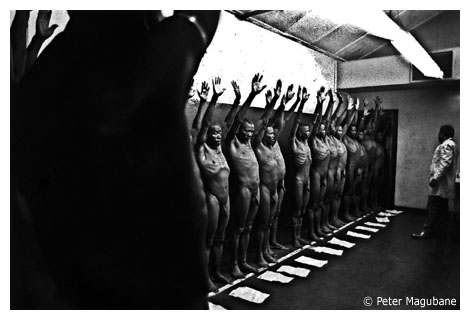

The first photograph, taken by Peter Magubane, the renowned black South African photographer whose visual documentation of apartheid earned him the tribute of being a “one man truth squad? — had shocked me.

I saw it first in Drik’s 2004 calendar. The picture was accompanied by the words of ?another South African, the internationally acclaimed, award winning playwright and poet Sindiwe Magona. As many of her readers know, Sindiwe had worked as a domestic before earning a graduate degree from Columbia University,

“Father worked in the gold mines of Johannesburg before I was born. I was in my thirties when I first laid eyes on Peter Magubane’s book of photos of “mine boys”. That book angered and disgusted me. But it wasn’t till I came to the corresponding part of my father’s life that a mule kicked me full in the belly. All this time, more than two decades after, the despicable things those photos depicted: grown men “naked as unpodded beans… dusted with sprayings of “DDT” and forced to show their anuses, regular inspection against theft of precious stones” — the vicious truth never penetrated my defences.

Father worked in the mines. Mine bosses did such things to mine boys. But that such things were done to Father never occurred to me. How do you look at the man you have known all your life as “Protector, Provider, Soother of spirits bruised” and admit to yourself he suffered unimaginable violation, endured unspeakable humiliation? How does a child love and respect a father and know that that man has been treated in a manner no animal ever suffered and know that there are many who saw him as less than human? How do you swallow a father’s bitter impotence?

I wept. When the realization hit me. When I could no longer deny that my father underwent such brutality, a sorrow so intense overcame me. And, I wept. For my father.

For all the men who had to leave their wives and their children, every year, for eleven months of the year, to go…

to a place of shadows, of dreams, of promises false.

Where lives are slighted, wasted, ill-used and squandered;

sacrificed to greed and need, real and manufactured.

Where rich men dream of richer riches;

and poor men die clawing at stones.”

— ?In Your Own Words?

Peter Magubane’s photo of the ?mine boys? belonged to the apartheid era as did Magona’s words — or so, I’d vaguely thought, until news of the massacre of 34 protesting mine workers on August 17 made the headlines (see pic 2), and raised questions the world over, more insistently, about the nature of the post-apartheid state in South Africa. About class inequality and workers struggles. About economic and social injustice as being integral to capitalism. About betrayals by national liberation leaders. About how a luta continua, Portuguese for `the struggle continues’ — the rallying cry for Mozambique’s war of independence — has increasingly been adopted by South African activists. Shongram cholcche, cholbei.

The Marikana mine workers had worked not at a diamond one, as Magona’s father had, but at a platinum one. However, as Nigel Gibson reminds us, South Africa was built on mining, specifically on cheap African labour — a truth which survives the abolishment of statutory racial apartheid. In other words, what was true for the colonial period when a white minority had ruled South Africa, is true for post-apartheid South Africa now, ruled by a black minority.

The massacre of workers at the Lonmin-owned mine demonstrates that the lives of ?mine boys? are no better off in post-apartheid South Africa. That the African National Congress’ (ANC) promise of liberating black Africans, particularly the poor, from ?political and economic bondage? is a false promise. That eighteen years on, lives are still being slighted, wasted, ill-used and squandered. That Nelson Mandela’s long walk to freedom has stalled, has been sacrificed to greed and need, real and manufactured.

That racial apartheid has been replaced by class apartheid, by the ?systemic underdevelopment and segregation of the oppressed majority through structured economic, political, legal, and cultural practices? (Patrick Bond).

That Frantz Fanon’s prophetic caution rings ever more true in today’s post-apartheid South Africa,

Before independence, the leader generally embodies the aspirations of the people for independence, political liberty, and national dignity. But as soon as independence is declared, far from embodying in concrete form the needs of the people in what touches bread, land, and the restoration of the country to the sacred hands of the people, the leader will reveal his inner purpose… In spite of his frequently honest conduct and his sincere declarations, the leader as seen objectively? is the fierce defender of these interests, today combined, of the national bourgeoisie and the ex-colonial companies…He therefore knowingly becomes the aider and abettor of the young bourgeoisie which is plunging into the mire of corruption and pleasure. (The Wretched of the Earth, 1961).

The Bench Marks Foundation, an independent South African faith-based organisation, which promotes corporate social responsibility, released a report in 2007, The Policy Gap ? A Review of the Corporate Social Responsibility Programmes of the Platinum Industry in the North West Province. The study, which researched the impact of the platinum boom on the 350,000 people living in the platinum mining areas of the North West, concluded thus,

much needs to be done in terms of the environment, housing, health, labour, waste management, energy and water management, clean air and geological issues. The report demonstrates huge negative impacts on surrounding communities and goes contrary to the popular myth that the benefits from mining trickle down to local communities.

Its conclusion was in stark contrast to the IFC’s report a year earlier (Investor Finance Corporation, the World Bank’s private sector arm), which had applauded Lonmin for its environmental, health, labor, and safety records, for its ?robust community development framework.?

A followup study by Bench Marks, released only two days before the massacre near the Marikana shaft drew attention to the ?appalling? housing conditions of Lonmin’s workers. It wrote of open sewers, of rampant diseases, and an ?unacceptable? level of fatal accidents. Of asbestos found in school buildings supported by Lonmin, of unguarded railroad crossings, and environmental degradation. Of the use of local tribal authorities to recruit workers (leading to favoritism and sexual exploitation), and an over-reliance on sub-contracted migrant workers, most of whom lived in crime-ridden informal settlements (Alex Lichtenstein, What Went Wrong At Marikana? September 1, 2012).

The 2012 report concluded, ?Overall, we have seen very little improvement in the performance of the companies surveyed on corporate social responsibility [since 2007].? A press release which accompanied the followup said, communities are hardly ever consulted about their frustrations over the impact of mining on their lives, the situation remains unchanged since the initial Bench Marks study conducted five years ago, and, that mine-owners are obsessed with cost-cutting, undertaken invariably at the ?expense of the environment, labour and communities.?

After the Marikana massacre, Bench Mark Foundation’s chairman Jo Seoka, refuted mainstream media reports which portrayed the protests and ensuing violence as caused by inter-union rivalry, by “turf battles” between the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), allied to the ANC, and the more militant indendent union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), which, as reports indicate had been unable to contain the militancy of the workers (Bill van Auken, WSWS, August 18, 2012).

It had everything to do with low wages, insists Seoka. With the disintegration of social ties, crime, murder, rape and prostitution, with unemployment and poverty which has ?created an incubator rife for worker and community discontent.? (Business Report, August 17, 2012).

After eighteen years of democracy, a mineworker earns only 3,000 [South African Rand, approximately $360]. The workers are demanding a 300% pay hike, i.e., monthly salaries of R 12,500.

Understandable, given that it is the workers who risk their lives and health to extract riches from beneath their feet, riches which make their way into the pockets of bosses and senior management of Lonmin. Understandable, given that the Lonmin platinum mine is the third richest in the world.

As Thandubuntu Simelane, a miner told South Africa?s Mail and Guardian daily, ?It?s better to die than to work for that shit ? I am not going to stop striking. We are going to protest until we get what we want. They have said nothing to us. Police can try and kill us but we won?t move.?

Seoka says, when he’d met Marikana’s workers before the massacre, they’d been “peaceful.” They’d just wanted the management to engage with them.

Two days after the massacre, Lonmin’s response? It issued an ultimatum, despite those killed having not yet been identified. Despite family and friends still struggling to deal with the horror of what had happened. If the workers did not return to work on Monday, August 20, they could be fired summarily, said the company statement.

The government’s response? The 270 miners who’d been arrested for protesting, were charged with the murder of their 34 colleagues, shot dead by the police.? The murder charge, brought by the national prosecuting authority under an obscure Roman Dutch law, had previously been used by the apartheid government against the ANC (the charge was later withdrawn). Initially, Lonmin had threatened to sack the striking workers. But only 8% showed up for work, protests have now spread to other Lonmin mines as well.

The police commissioner general Riah Phiyega, a political appointee, insists that the police had acted in self-defense, that the miners had surrounded and attacked the police but postmortem examinations reveal that most miners had been shot in the back. An academic reconstruction, done by a University of Johannesburg professor who’d gone to the site and interviewed workers and witnesses, reveals that the police had surrounded the workers, had put up barbed wire fence, leaving only a very narrow opening for the workers. While a lot of the media coverage shows that the workers are rushing towards the police who seem to be retreating, says Vishwas Satgar, the workers were actually running toward the opening. At least ten were gunned down at the opening.

In post-apartheid South Africa, rich men who dream of richer riches now includes blacks such as, Cyril Ramaphosa, the former NUM president who has become one of South Africa’s richest millionaires, who has a seat on the board of directors of Lonmin. Who, besides mining, has interests in the financial sector, advertising, information technology, property, telecoms and retail.

In post-apartheid South Africa, poor men still die clawing at stones. Their struggle for freedom from economic and political bondage continues, as does that of workers the world over. A luta continua. Shongram cholcche, cholbei.

———————————-

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.