Rahnuma Ahmed

Homes, sweet homes

WHAT does home mean for Palestinians driven away from their land in recurring waves of Israeli onslaught ? 1948, 1949 to 1956, and again in 1967, due to the six-day war? What does home mean for first generation Palestinian refugees, and for their descendants, for people who ?yearn for Palestine??

It is a yearning that permeates, in the words of David McDowall, the ?whole refugee community?, one that stretches from 986,034 in the Gaza Strip, 699,817 in the West Bank, 1,827,877 in Jordan, 404,170 in Lebanon and 432,048 in Syria (2005 figures). What does home ? something that ?exists only in the imagination? ? mean for Palestinians who are subject to Israel?s ongoing colonisation of Palestine?

?What, for you, is home?? ?How would you represent it?? ?How would you represent it if you were to take one single photograph?? Florence Aigner, a Belgian photographer, put these three questions to Palestinian refugees living in the West Bank, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. She gave them time to think and returned with her camera and notebook the next day to take two photographs: a portrait of the person, and a representation of what home meant for that person, both visually, and through words. Personal narratives are often lost in collective narratives, and Aigner says she wanted to explore both diversity and particularity through the experiences of daily living. Her approach, she says, allows her to create a dialogue between the person and her or his idea of a home, between the photograph and the photographer, and also, between photography and writing. And thus we find images of home in exile interspersed with images of home in Palestine, images where one home is often projected on the other. These images form her exhibition, Homes, sweet homes.

I had always felt homeless, says Eman, and had refused to cook, `to practise home?. But now, even though our house in Ramallah is temporary, I have started to cook, cooking for me is ?an act of love?. For Oum Mahmoud, home is her husband who was killed in a Mossad air attack. Her house in Ramallah was destroyed in a recent Israeli missile attack, the new flat has ?no memories?, ?no furniture?, it is like living in a hotel. For Wisam Suleiman, home is orange trees and lemon trees, and the faces of martyrs who have given their lives to assert their right to return. The way home, says Suleiman, is ?sweeter than home itself?. For Abu Majdi, forced to flee in 1948, home is the ?key of our house in Jerusalem.?

———————————————————————

Photographs and interviews by Florence Aigner

Being on the margin, following my own footsteps, I always felt homeless. It made me develop a sense of rejection mainly for the kitchen, the heart of practising home. So I refused psychologically and practically to cook.

Last year, I had to move with my husband and our two children to Ramallah when passing back and forth between Ramallah and Jerusalem became an Odyssey trip due to the Calandia checkpoint and the harsh siege imposed on the city. Our house in Ramallah is temporary, I started to cook and feel good about it, cooking became an act of love I dedicate to my family. Is this home?

My home is my husband. I have only a few photos of him left. He was killed during an air attack by Mossad on the office of the PLO in Tunis in 1986. In the 90?s I could return to Palestine with the Palestinian Authority. Since then I live in Ramallah.

I have recently lost everything, my house burned when an Israeli missile hit it. I could only rescue some books and photos from the flames. Now I live in a new flat, but I have no memories or furniture left. I buy little by little some stuff to furnish it. I have the feeling to live in a hotel.

When I hear the word ?home? orange trees and lemon trees come to my mind as well as faces of hundreds of martyrs who have given their life for the right of return. For me, the way of return has to go through education, education, education…and books.

As Palestinian refugees we have to prepare the new generation to return to Palestine in a human way. We have to carry our culture and science with us, and work hard. The way home is more beautiful than home itself.

My home is my house in Malha near Jerusalem that we had to flee in 1948. I hope to return there one day, but I am not very optimistic, because Israel wants a land without its inhabitants. Sometimes I don?t understand anything. Before 1948 we had Jewish friends, we were living together. In 1948 we had to leave everything behind and we became refugees in Aida camp, Bethlehem.

An Iraqi Jewish family, the Rajwan moved then into our house in Jerusalem. We were friends and were giving gifts to each other. We saw them until 1967. I remember the grandfather used to say that he wanted to return to Iraq and to give us back our house. He said that they were keeping it for the day we could return. Eventually the old man died without having been able to return to Iraq. Me, I have kept the keys of our house in Jerusalem all my life.

————————————————————————————–

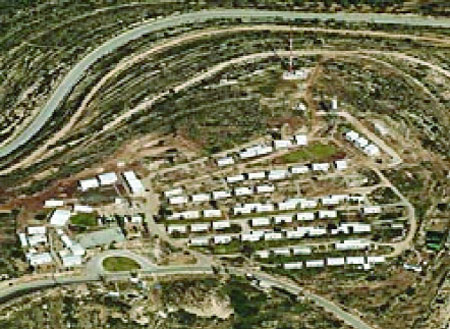

The architecture of occupation

Migron in occupied West Bank is a fully-fledged illegal settlement of Israelis, comprising 60 trailers on a hilltop that overlooks Palestinian lands below. In 1999, several Israeli settlers complained to the mobile phone company Orange about a bend in the road from Jerusalem to their settlements that caused disruption to their phone service. The company agreed to put up an antenna on a hill situated above the bend. The hill was owned by Palestinian farmers, but their permission was not required since mobile phone reception is a ?security? issue. Mast construction began, while other companies agreed to supply electricity and water to the construction site on the hill. In May 2001, an Israeli security guard, soon followed by his wife and children, moved to the site and connected his cabin to the main water and electricity supply. Less than a year later, five other families joined him. This is how the settler outpost of Migron was created. Soon, the Israeli ministry for construction and housing helped build a nursery, while a synagogue was built from donations from abroad.

Eyal Weizman, dissident Israeli architect and architectural theorist of the relationships and exchanges between architectural and military planning, documents the processes of illegal Israeli settlement ? in his words, ?a civilian occupation?. His book Hollow Land: Israel?s Architecture of Occupation provides a detailed and exact account of ?how occupation works in practice?. Weizman had, at the invitation of the Palestinian authority, also been involved in planning houses for Palestinians, in re-using settlements after the Israeli evacuation of August 2005. What is to be done with settlements after evacuation? Are they to be abandoned, reused, converted, or recycled? The Palestinians, he says, had rejected these single family homes as suburbs. After intense discussions, it was finally agreed that the evacuated shells of settlement would be spatialised into a set of public institutions: an agricultural university, a cultural centre, a clinic for the Red Cross, etc. But the project of re-using the illegal settlements collapsed after the Israelis destroyed them.

Settlement planning and building of the Israelis, says Weizman, emerges out of ?organisational chaos?. The very nature of Israeli occupation is one of ?uncoordinated coordination? where the government allows ?degrees of freedom? to rough elements, to a whole host of actors ? Israeli settlers, mobile phone companies, utility firms, state institutions, the army, etc ? and then denies its involvement. Micro-processes, such as that of an Israeli civilian moving a cabin to an illegal site, settling down, home-building, foreign donations pouring in to build a synagogue become wheels in larger processes of occupation of Palestinian lands. In the Israeli government?s colonial policies.

And as these occur, home-building for Palestinians ? even in the sixtieth year of their mass exodus ? remains something that exists ?only in the imagination?.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.