by Rahnuma Ahmed

I cannot say when I grew up but I think as you grow older you change in such a way that…it

influences you. Growing older influences you.

? A 22-year-old polytechnic student

Girls from better-off homes are like broiler chicken (farm-er murgi).

? A 19-year-old college student, photographer

How it all began

At times curious, ?I don?t know which end the baby comes from, please include that in the book.? At times plaintive, ?All these grandmotherly types in the village said, if a boy so much as touches you, you?ll become pregnant. I was terrified, I kept shrinking and slinking away for years and years…? On occasions stroppy, ?And yes, you must include a section on pills,? ?And there must be a discussion on why wives are not to blame if a girl child is born,? ?Also, when a wife is pregnant and starts feeling less y?know, but her husband keeps insisting, can you please have a discussion on how long they can do it, without the baby being harmed?? On others giggly, ?And yes, tell those boys that not all girls are to be looked at as (future) wives, but as sisters.?

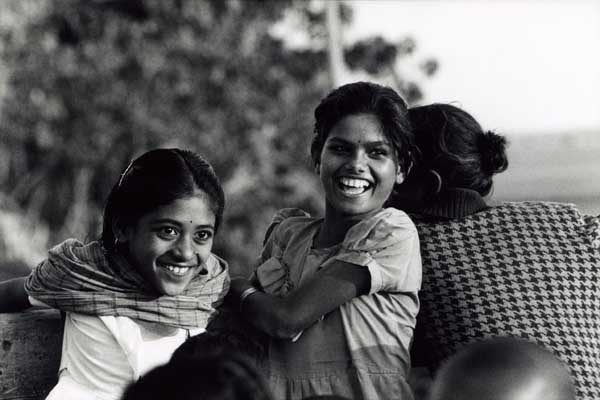

The idea of putting together a resource book for girls and young women on adolescence grew out of listening in to the whispered conversations of the Out of Focus girls when they stayed with us overnight, some of them for weeks, sometimes more than a month or two, to prepare for their coming matriculate exams. It was the name that a young group of boys and girls of low-income families, who Shahidul trained in photography for many years, had chosen for themselves. And then there was Nahar, who grew up piggybacking on Shahidul, whose mother worked as a peon in the office facing our flat. And also, my experience as a university teacher at Jahangirnagar, where women students, sometimes from other departments as well, would seek me out for advice.

The idea took material shape much later when RIB (Research Initiatives Bangladesh) agreed to fund the initiative of writing a resource-book, a book that would include both information which girls had sought but were denied (?My bhabi said, you will find out when it happens?), or didn?t know who to ask, how to ask (?I was curious but afraid of asking my elder sister, she?d have thought I was a bad girl?), and also, their own life-experiences of growing-up. Books for adolescent boys and girls, increasingly made available by NGOs, are generally authored in a seamlessly whole adult voice, one that ?talks down? to adolescents. Adolescence is viewed as transitional, a stage of life, as a problem requiring solutions, rather than a period marked by ?specific psychosexual development? (Walkowitz, 1980). Gender dynamics, processes of thinking and feeling, informal power, and cultural conceptions of the self are ignored. The need for a nuanced appreciation of material realities, of subjective fears, dreams and aspirations is generally absent. Instead, one sees an over-reliance on the need for disseminating medical, scientific knowledge, totally oblivious to more recent feminist critiques that call for the need ?to reintegrate the whole person from the jigsaw of parts created by modern scientific medicine? (Koeske, 1983).

The manuscript was co-authored. Rima, Shetu, Shopna, Moly, Brishti and Doly from Out of Focus, and Nahar, were joined by other girls from the social margins, Epy, Khincchin, Nomita, Lokkhi, Pensila, Maria, Runu, Shebika and Anju, a total of sixteen writers who were assisted by three women anthropologists, Shah Afroditi Panna, Rajina Sultana and myself. The work is now in its final stages.

Tales of growing-up: contributing to family incomes

Girls from social and economic margins contribute to family incomes rather than being dependent, as is the norm in middle-class families. Lokkhi, 21, whose father had retired from the lowest rungs of government service, who had a brother who ?didn?t count, he doesn?t look after us,? provides for her family?s food expenses by tutoring several schoolchildren, and doing appliqu? embroidery on saris. Brishti?s, 19, father died when she was young, her only sibling is an elder sister, a garments factory worker. ?After my sister got married, I began supporting my mother and myself, I was on ETV?s Mukto Khobor but the neighbours were suspicious, `She must be up to some tricks,? they said. Both Lokkhi and Pensila studied at the Open University-run schools, in addition to earning incomes.

Pensila came to Dhaka to work as a domestic help, leaving behind her parents and three siblings, a family of marginal farmers in Chapainawabganj. Her father?s sudden death caused her to leave Dhaka, and we lost contact with our youngest co-author, who was only 14. Shebika, 20, and Epy, 17, two Chakma sisters from Khagrachari, had recently come to Dhaka to join their older, married sister who works in a garments factory. Shebika entered factory work, while Epy took charge of running her sister?s household. The family had lost their home, land and livelihood due to military atrocities, and had been forced to flee to refugee camp life in Tripura, India for ten years. They returned to Bangladesh in the mid-1990s, but impoverishment had already set in. Another co-author was Nomita, a petite sixteen-year old, whose father works as a school guard. Unsuccessful in her Matric exams, Nomita was dolefully considering taking them again, as she sewed chumki on shalwar-kameez-orna sets, piecework that contributed a steady trickle to her family income.

Most of our co-authors described childhood as a time when they ran around freely, played with boys, and had not a single care in the world.

Tales of growing-up: attraction, love and desire

I quizzed Pensila. ?Yes,? she said, ?I would talk with the other girls.? About? Well, marriage. And? You have to leave your parents. And? Well, the husband… And? I feel shy. Go on, I urged her. You have to sleep beside your husband, she burst out and blushed. Both of us giggled uncontrollably.

Another co-author had said, when I was at home, in the village, I would enjoy it when my boudis (sisters-in-law) would sit and ?talk dirty?. Rabeya spoke of her own awakenings when she and close friends would sit and pore over a love letter, sent to any one of them, re-reading it for the umpteenth time. Nomita recollected how, soon after her periods began, her cousins? wives would tease her mercilessly, ?Now we can marry you off. We will make you jealous. We will keep your husband for a night.? One of us had asked Lokkhi, what is sexual desire? Do women feel it too? She replied thoughtfully, ?It is not something that one gives but something that one shares, like say, a husband and his wife, between the two of them.?

Another of our co-authors told us, ?When my sister doesn?t give in to her husband, and they quarrel, my other sister cautions her, ?If you don?t, men are likely to heat up and suffer from a stroke.?? Dhaka Community Hospital was a partner in the writing project, the medical staff ? from doctors to nurses to paramedics ? gave generously their time and attention to write answers to a long list of questions drawn up by our co-authors (?we want to know what the doctors think, what science says,? was a common refrain of many of our co-authors). We related this incident to Dr Quazi Quamruzzaman, its chairman, and an old friend of mine. We sought his medical opinion. Flabbergasted but quick to regain his composure, Zaman bhai tersely replied, ?Tell them to bang him on his head.?

Tales of growing-up: parents as sexual

The older co-authors spoke of how mothers often relate to them, their own experiences. Parents have to sacrifice their own needs and desires because the children have grown up, one of them said. ?We lived in a single room, even that is one thousand to twelve hundred taka rent. Dhaka city is so expensive.? Another spoke of her family?s circumstances, ?My sister?s husband died when she was in her early 20s, she returned to live with us. My mother decided, from now on, we will sleep separately. But my father wanted to sleep beside her, he wanted to touch her, to feel her beside him.?

?We had moved to a new home, a large-ish room,? related one of them, ?sixteen hundred taka rent. My elder brother got married, they slept on the newly-partitioned side, while us four siblings slept on the bed. My parents slept on beds made on the floor. There was a daughter-in-law in the house now. My mother became very careful, she wouldn?t let him. But now that my father has passed away, she feels sad. She says, he must have been hurt.?

Rabeya beautifully summed up one of our intense night-long discussions, ?The problem is not theirs. It is ours. They were unable to tell us that they too, had wanted. And, of course, we never tried to see things from their perspective.?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.