Design: Mahbub/Drik

We spot a lens peering at us from the corner of our eye. Immediately we straighten up, fix our hair, smooth the rough in our clothes, consciously make – or avoid – eye contact. Only the well trained is able to visibly avoid responding to the camera?s presence. The professional photographer prides in her ability to take ?natural? photographs, where her intervention is invisible. Yet, peering through family albums, wedding folders or a Facebook status we find ourselves actively inviting the portrayal of how we want to be seen. Whether we consider a photograph of ourselves to be ?good? largely depends on how well the photographer has represented us, as we would want it. As such the photographer?s success depends not so much on her aesthetic sense or insight, but on her ability to please the sitter. While this applies to the casual portraitist, it is much more true of the professional photographer. Her bread and butter depend on a satisfied client and as such, are driven by an external agenda. Whether it be a corporation, or an NGO or a newly wed couple, a good photographer is one who delivers what is required.

Few professional photographers have been able to overcome this desire of the sitter and stamp her own personal style on the image. Some have acquired a fame, or even notoriety and are sought for the uniqueness of their style, though in the final analysis, that too has to be ?accepted? by the sitter for it to work. Others are able to create their own imagery and convince the sitter that this image, different though it might be, is an acceptable, and by implication flattering representation. The cult status that some of these image-makers acquire, helps and indeed necessitates such positions.

The amateur, freed from such inhibitions, can flit across this landscape with far greater ease. Her magic carpet, unburdened by commercial pressures, liberated from the need to preserve a public persona, with the love of the medium as the only driver, can create images merely to satisfy her own curiosity, nurture her passion, indulge in her fantasies.

Advents in technology have eased this process. No longer must one labour in a darkroom to bring out the most delicate tones of an elusive image. The ubiquitous mobile phone has replaced the heavy lens, the ungainly tripod, the strained back and the empty wallet that early photographic processes led to. The ability to work in low light, to be a fly on the wall, to blend in a sea of others busy making selfies, allows an invisibility that professionals struggled to cultivate. The joy of making an image is the only reward the amateur seeks.

The photographic tradition in Bangladesh has seen a dramatic shift. There was a time when the representation of the nation was largely through the image making of visiting photojournalists or NGO workers. An imagery fitting in with the media stereotype of a failed state was how the world saw Bangladesh and Bangladeshis. The economic rise of Bangladesh, despite its woes, has questioned the basket case tag that Kissinger had bestowed upon us many years ago. More significantly, one of the most remarkable photographic movements, spurred in many ways by the innovative photo agency Drik, and the photo school it birthed, Pathshala, has led to Bangladesh becoming a role model in documentary photography. Bangladesh today, is largely represented by a group of talented, committed and highly skilled photographers who have emerged from the school, one of the most respected in professional circles.

In the slipstream of this emergent talent has grown a group of keen amateurs who have flourished in this fertile environment. Inspired by their mentors, egged on by their peers, immersed in an environment where the festivals, workshops and lectures offer regular intermingling with the finest in the profession, Bangladeshi amateur photography has reached new heights. Gone are the hackneyed set pieces, which are adored by camera clubs, the gimmickry so prevalent in tech loving salons, or the rehashed super saturated imagery typical of special effects gurus. They consistently produce fresh, vibrant and original images their professional peers would be proud of. The book combines their work with a limited number of images produced by professionals. The latter, is not commissioned work designed to promote a product or a project, but life seen in the raw. Ordinary life made special because professionals with a trained eye, whose love of the medium has helped them attain amateur status, saw it differently.

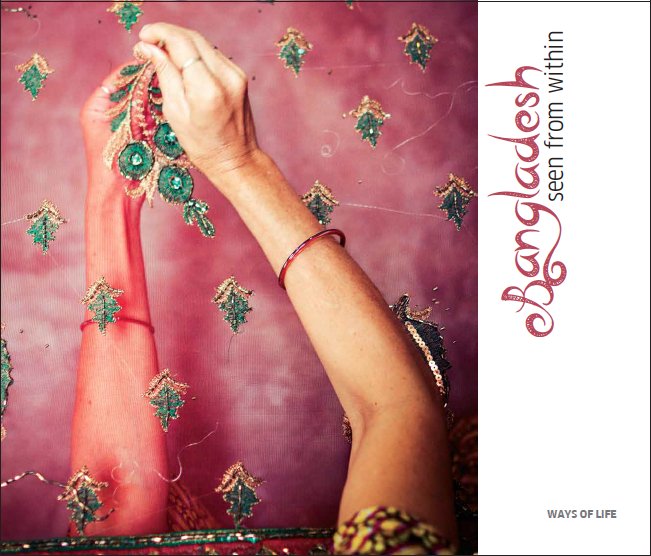

Twenty five years ago, when we set out to lay stake to our own identity, we hadn?t realized we were transforming the way we perceived our nation. Despite all the things that are not right in our nation there is much reason for hope. This rich, nuanced, insightful look at our community is the look of pride of a nation with self-belief. It celebrates both the power of photography and it celebrates the power of our photography. By embracing the amateur, it also ensures that the most dynamic of art forms will not merely be a plaything for the elite and that the transformative power of the medium will be an agent for positive change. This anniversary book, the first of a series presenting Bangladesh today, is an ode to photography and Bangladesh seen from within. It is also a celebration of life.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka 2nd November 2014

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.