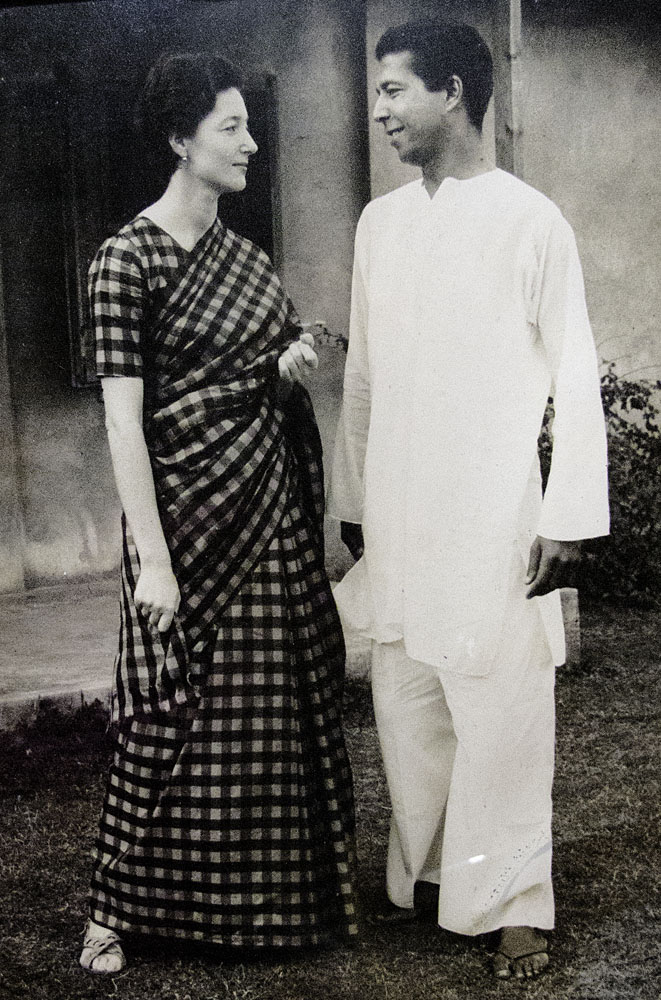

I would kiss her on the lips and she would perk up and say “Ah, a real kiss”. Chotomami (little aunt) had always been special. Luise Morawetz-Rafique (1.1.1929 – 9.7.2013) was the only white person in our family, and we were naturally curious. My mama (mother’s brother) had many foreign friends, and I would occasionally be taken to the Dhaka Club, an old colonial club that I now avoid on principle. As a child, going to the swimming pool, having marshmallows and seeing naked white men changing in front of us, were all things that led to endless conversations amongst the rest of the kids. Chotomama and mami had two daughters Laila and Laeka and a son Akbar. We were all close in age, but Akbar and I, boys, mischievous and with boundless energy, were the closest of pals. We were also constantly fighting. The two girls were the heartthrobs of all the older boys, and I by being a close cousin and thus a stepping stone, got special treatment from the boys. They were fun days.

My uncle was brilliant, talented and charming. He was also an alcoholic and prone to being violent. We were scared of him. It was Chotomami who made their home warm and inviting. She would take me aside and tell me things that she thought I should know. It made me feel very grown up. She was a friend as much as an aunt. Chotomami had beautiful handwriting, and mum would often send me over to be coached by her. The pinewood house in Rajarbag, sent all the way from Europe by Chotomami’s dad as a wedding gift, had a sloping tiled roof.’ With an exquisite rose garden, mosquito netting on the windows and commodes in the bathroom, it was the only house of its kind in town and it always felt special walking in. Chotomami was also a good cook, so the handwriting lessons were always a treat. But it was only as an adult, that I got to know my aunt. She would reminisce, share secrets, talk about how she fell in love, dealt with her in-laws, learnt to eat with her fingers. Through her, and her stories of adjusting with a Bangali family, I learnt things about my own kin that I would never have gleaned on my own.

War broke out in 1971 and Chotomama packed off the family overseas. For a while we moved into the pinewood house, but with the realities of occupation and without the original occupants, the house no longer had the same magic. Without Chotomami, the home had lost much of its warmth. It was many years later that we caught up. I too had left at the end of the war and came back after many years. Chotomami had struggled to cope with a difficult husband. They had separated for a while, but she came back. Chotomama had set up the Bangla section of Deutsche Welle in Germany but returned to Bangladesh after retirement. The couple had settled in my grandfather’s house “Sans Souci” in Khulna.

Relative to Dhaka, Khulna was a sleepy town and my uncle with two old Mercedes Benz cars, was the talk of the town. But while my mama loved the attention, it was the quietness of Khulna where Chotomami found peace. It has been many years since Chotomama passed away. The children had all settled overseas. The Austrian memshaheb decided to stay in Khulna. San Souci was her home. She became a regular church-goer and her volunteer services included teaching English. As she had done for many years at Viqarunnisa Noon School she continued teaching and gardening until the very end.

On a flight to Jessore, while escorting Chotomami to Khulna, I met my old friend Khaled. We used to be tennis buddies. We were top seeds in the tennis championships at the Officer’s club in Dhaka. I had boycotted the tournament in protest against Pakistani occupation. Khaled had gone on to become champion. We had hardly met since then. He had just gotten married and was flying to his parental home with his new bride. Leaving home is traumatic for many a Bangladeshi bride and Khaled’s wife was sobbing on the plane. I remember Chotomami going over to him and saying “You must tell her you love her. Every day. “These were words she had missed in her own marriage, but I had taken her lesson to heart. It was not sufficient to love, Chotomami had told me. You have to express it. Over and over again. On the many occasions when the strains of our activist lives had stretched the relationship between me and my partner Rahnuma, those words of wisdom have come to the rescue. “It is not enough to love. You have to tell her you love her. Every day.”

My cousin Asmi rang to say Chotomami had fallen from the ladder in the rooftop of San Souci and broken her hip. Not trusting the medical facilities in Khulna, they had sent her to Dhaka for treatment. She was being taken by ambulance to Lab Aid in Dhanmondi. I quickly cycled over to Mirpur Road and found Chotomami lying on a stretcher. Even on the stretcher bed, she perked up on seeing me. She liked being kissed. The doctor, seeing an elderly white woman, quite frail, turned to me and asked how old she was. Chotomami peered over the sheet and chirped “bao ki tao”. I’ve rarely seen a doctor so charmed. “Twelve or thirteen” was what it meant. The phrase drew on old tradition when a girl over thirteen was considered too old for marriage. It is no longer in use, but the humour didn’t escape the good doctor.

Even till the very end, Chotomami would remember everyone’s birthday. For as long as I can remember, there would be a birthday card with her neat writing. Posted well in advance, so it would reach me in the UK well in time for my birthday. It was the same for all our cousins. Sadly, we had rarely reciprocated. and as Chotomami got older and as technology changed, the greetings would come through emails, later through SMS. Far more dutiful than I, Rahnuma would send her books, soap, or perfume, or a handmade card. But Khulna was far away, or so we perceived it. Our busy lives had little room for Chotomami, tucked away in Sans Souci. But she would write, in response to an article Rahnuma had written, or some news item about me she had read in the newspaper. She was a proud aunt. It was only when she could no longer walk that her text messages carried that hint of sadness. Practical till the end, she had made all arrangements for her funeral. She had no intention of being a burden on anyone, even upon death.

I only went once to visit her in Sans Souci. She took me all round the house, showing me the photographs that remained her companions. The twinkle in her eyes followed me down the stairs as I kissed her one last time. On the lips. “A real kiss” were the last words I heard her speak.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.