The Afghan Box Camera is a simple box-shaped wooden camera traditionally used by photographers working from a street pitch, who produce, by-and-large, instant identity portraits (aks: ???) for their clients. In Dari the camera is known as?kamra-e-faoree ().which means ‘instant camera’. It’s also less frequently called kamra-e-faoree-e-chobi (instant wooden camera) or kamra-e-chobi (wooden camera). In Pashtu the camera is sometimes referred to as da lastunri kamra (sleeve camera: ??????? ?????) because of the sleeve on the side of the camera that photographers insert their arm into.

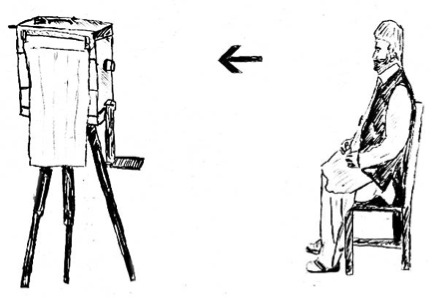

Customers pose for photographs sitting on a chair against a material backdrop. The lens of kamra-e-faoree are shutterless, so in order to take a photograph, and working only with natural light, the photographer (called akass [????]) whisks away the lens cap with one hand to expose the photographic paper on the inside of the camera; he then replaces the shutter and inserts an arm through a light-tight sleeve giving him access to the camera’s interior which doubles as a darkroom. Inside the camera, he develops a paper negative of the image he has just taken. He then shoots this negative (‘film’) to make the positive (‘positive’), and finally develops the positive to produce a finished photograph. A film of the process can be viewed here.

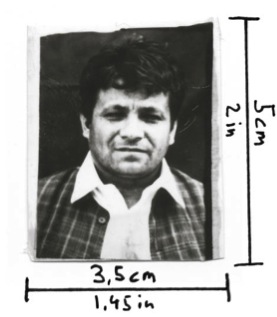

Here?s a sample kamra-e-faoree photograph showing the typical dimensions of a passport size portrait.

Because the photographs are immersed in a bucket of water for cleaning, they are sometimes known as aks-e-awi (water photographs). Below Mirzaman cleans a finished positive image.

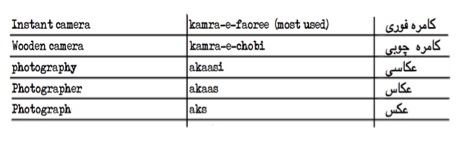

Here are some Dari translations for words commonly connected to the kamra-e-faoree.

The camera is completely manual ? it does not use electricity – while the photographic process is analogue: using chemicals and paper; there is no film (references to the ?negative? paper print by photographers should not be confused with negative photographic film). Inside the camera the paper prints are developed with the aid of an eye-hole on top of the camera allowing the photographer to follow the development process, and by touch.

The camera was made by carpenters. A renowned carpenter in Kabul whose name we heard frequently was?that of Ali Ahmad-e-najar (najar?means carpenter) who had a workshop on Jeddha Maiwand. Below is a gallery with Manawar Shah buiding a kamra-e-faoree based on the design of Mia Muhammad‘s old camera. A manual with step-by-step instructions on how to build a kamra-e-faoree can be found here.

It was important that the camera be made of strong wood and that it be resistant to the elements as well as the day-to-day shunting about that it had to endure – because the cameras were regularly knocked over by scurrying children, inattentive passers-by, and on occasion authorities randomly exercising their power.

Photographers added their own lens, the only ‘foreign’ and the most expensive component used to make up the camera.

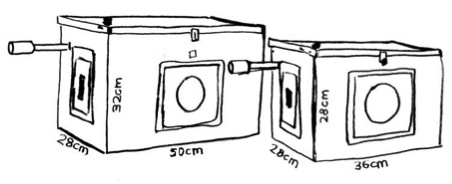

The basic design of the camera was more or less standardised although the size of kamra-e-faoree varied with location. In Mazar-e-Sharif and Herat we came across more compact sized box cameras than those we found in Kabul, Jalalabad and Peshawar.

Below are the sketches of a big camera from Kabul, and a small camera from Herat.

The look of the camera varied from photographer to photographer. Here?s a gallery of images of various kamra-e-faoree we came across. Many of them had to be resurrected from dusty backrooms for us to view.

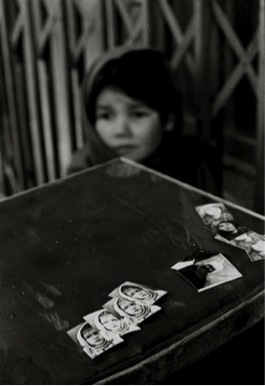

Traditionally kamra-e-faoree like these had a display frame on the side of the camera exhibiting the photographer’s work. Below: Mia Muhammad’s display on the side of his camera which also includes colour identity photos and photographs of his friends, who were also kamera-e-faoree photographers.

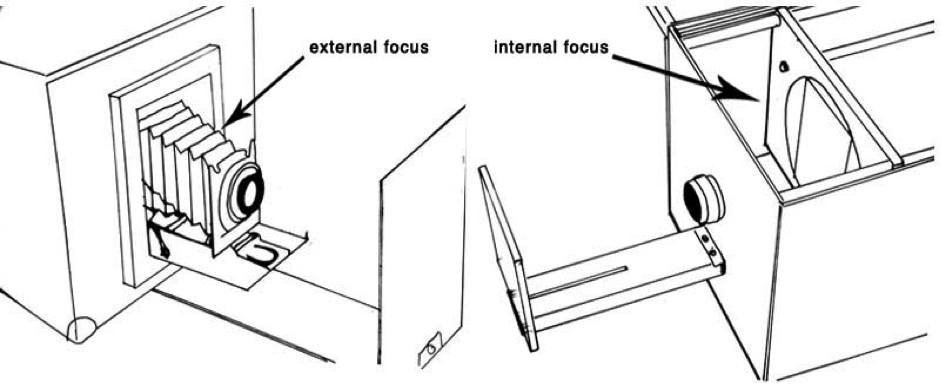

While cameras similar to the kamra-e-faoree,?and using identical developing processes are found world-wide, there are differences between kamra-e-faoree and non-Afghan box cameras in design and function. In neighbouring Pakistan the paper negative box camera was known as the ‘minute camera’ and often had an external focusing system, while the sleeve to enter the camera was found at the rear.

The origins of the camera are somewhat obscure.

Though there is evidence of box cameras similar to the Afghan variety at work in the pilgrimage city of Mashad, Iran in the early 1950s and possibly earlier, it seems feasible that the kamra-e-faoree arrived in Afghanistan from the Indian sub-continent given the history of commercial traffic between India and Afghanistan, and the extremely rich history of photography in India; a number of photographers assume as much, while also recalling that there were Indian studio owners who possessed kamra-e-faoree in Kabul in the 1950s or earlier, during the reign of Zahir Shah (1933-1973).

The long-reigning monarch, Zahir Shah in 1963.

Rather than mentioning a year, photographers tended to refer to the era of a national leader to indicate the epoch they were discussing, or mention an important event such as ?during the war? (civil war) or ?when Karzai came to power? (the current president).

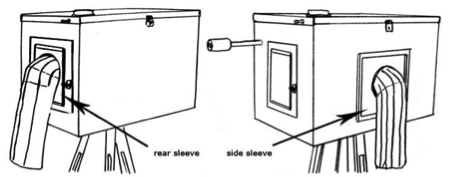

The wall of the Zalmadi studio in Herat, below, with portraits of many of the former rulers of Afghanistan and the proprietor’s grandfather, is a case in point.

Because of the lengthy duration of some of these ruling periods and epochs, exact dates are hard to pin down.

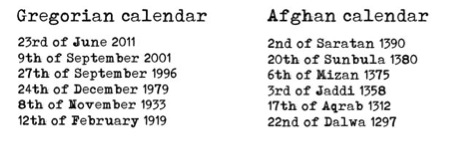

The earliest date we we can be certain that box camera photographers were working in Kabul was in the early 1950s, though it is possible photographers were using the camera in the 1940s, or according to the Afghan calender, the 1320s.

Generations of Afghans have had their portraits taken by kamra-e-faoree photographers. Some of these photographers learnt the trade from their fathers or another male relative, while others were taken on as apprentices by established photographers of no relation. Many started so young they were initially dwarfed by the camera and would have to use a chair to operate it, as can be seen in the image below.

In the early days of box camera photography in Afghanistan it wasn’t wholly unusual that photographers would be confronted with a cliental – particularly if they came from rural areas – for whom photography represented an alien magic.

In some cases these pictures would have been the first images their customers had seen of themselves – or would ever see; occasionally photographers even had to convince clients that the image they had just taken was indeed their likeness ? not, as we were told on one occasion, a mirror.

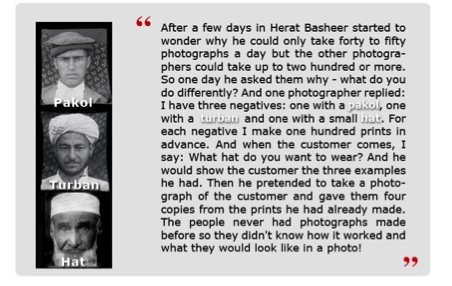

The story below told by Hafeez from the Ramprakesh studio in Kabul about a photographer called Basheer (the brother of Rona) who went to Herat to work as a box camera photographer sixty years ago illustrates the newness of photography for Afghans at the ti

It should also be noted that the religious establishment in Afghanistan at the time frowned on photography for theological reasons. Islamic clerics argued (and still do) that reproducing the likeness of a living creature was the responsibility of Allah (God) alone, not that of any other human. In ecclesiastical eyes reproducing human as well as animal images was tantamount to being a Kafir?(a non-believer), not a pious Muslim.

This would again prove to be a thorny issue when the Taliban rose to power in Afghanistan in the 1990s, banning the public display of images of living beings.

Sometime around the mid-1950s the oldest of kamra-e-faoree photographers speak of a boom in the numbers of their kind in Kabul.

This was, they say, as a result of a governmental drive to distribute national identity cards countrywide, with a photo attached.

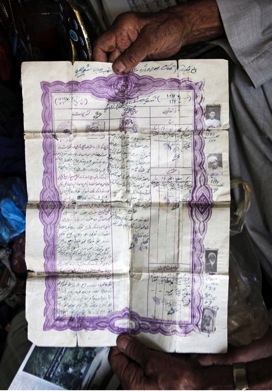

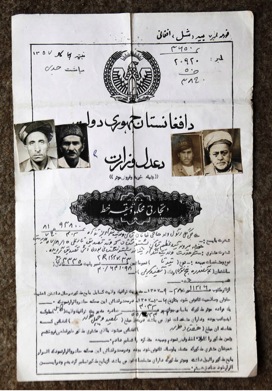

In modern-day Afghanistan photographs have for decades been affixed to a multitude of official documentation: children?s school cards; soldier?s identification; driving licenses; as well as being attached to legal documentation such as that necessary in property disputes and ownership.

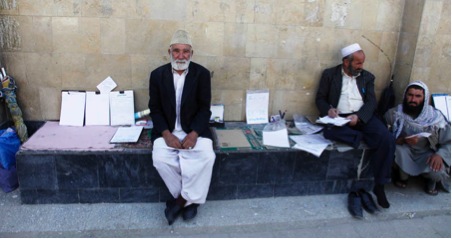

Below on the left is a deed of title for a property in Herat with box camera photographs positioned down the right side of the document; it’s over half a century old. Opposite that is a car registration certificate issued in Jalalabad with box camera photos, also on the right-hand side.

Courtesy of Sultan Hamidy.

Courtesy of Haji Afridi.

However, the mainstay of the kamra-e-faoree photographer?s trade in the early days, was it seems, to provide photographs for the Afghan national identity card: the?tazkira.

The tazkira is the most important identity document in Afghanistan; currently, it is obligatory for males, optional for females, and can be issued from birth.

This is a gallery of images of a pre-1992 tazkira in the form of a 20-page booklet (post-1992 the tazkira came in large certificate form, which is usually photocopied into a handy size to fit in the shirt-pocket.)

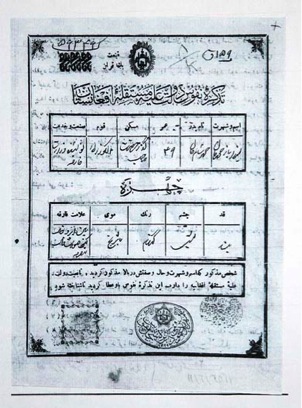

Tazkira are around in one form or another a long time. Below is a photocopy of a tazkira from 1920 which didn’t require a photograph. If you look at the bottom right-hand corner of the photocopy, you’ll see a thumbprint, which was also considered a form of documentary fidelity in Afghanistan.

Courtesy of the National Archive, Kabul.

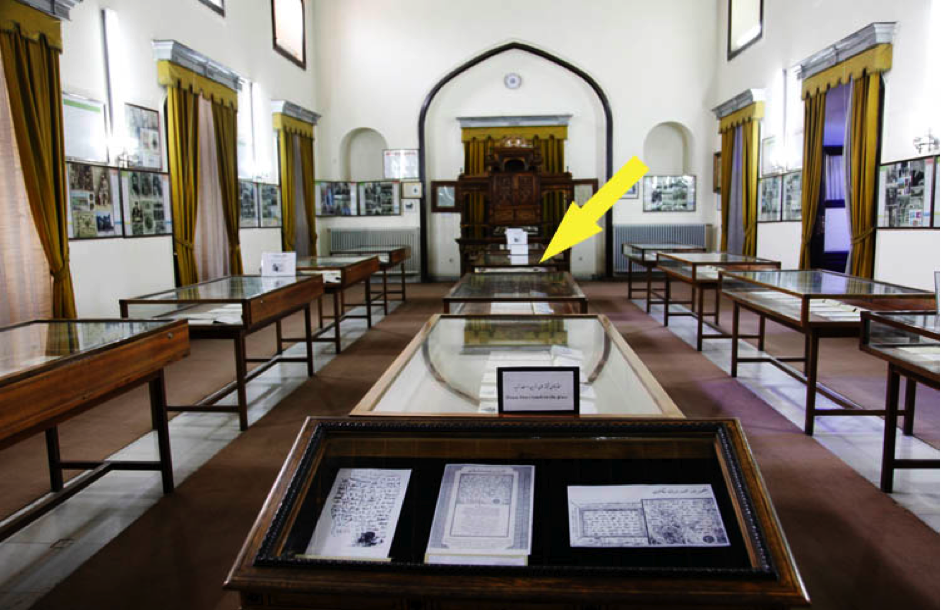

And here?s where you?ll find it in the National Archives.

The plan to attach an identity photograph to the tazkira is likely to have been a turning point in kamra-e-faoree photography in Afghanistan as it provided, with masses of potential customers, a steady and guaranteed income for photographers. After a nationwide government contract was awarded to take the photographs, dozens of new kamra-e-faoree photographers were trained and sent to towns and villages all over the country.

According to photographers in Kabul, it was a civil servant called Afandi who won this contract; as a result, he, along with his business partner Ahmadin Taufiq was directly responsible for training a cadre of kamra-e-faoree photographers in Afghanistan in the 1950s; who would of course go on and train other photographers.

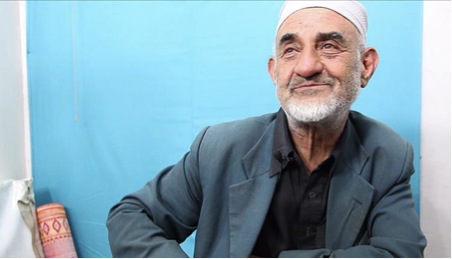

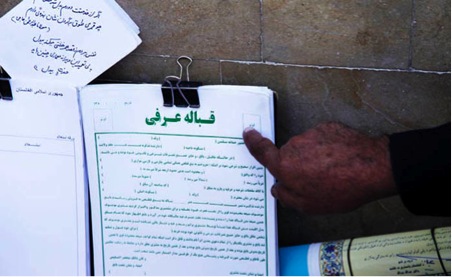

The knowledgeable Muhammad Usman pictured below claims Afandi was responsible for making the very first Afghan kamra-e-faoree.

Here?s his story.

Requiring only a minimum of equipment, kamra-e-faoree photographers were mobile, capable of providing identity photographs quickly, and they could do so very cheaply, making kamra-e-faoree photography the first type of photography that was available relatively en masse in Afghanistan.

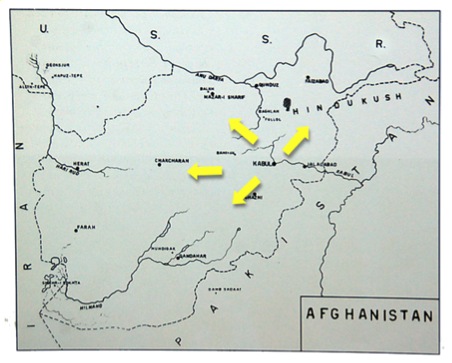

Newly trained, photographers travelled all over the country, sometimes to remote villages where they were accompanied by government officials to fill in the paperwork and issue a tazkira on the spot. The officials would also act as age-guessers since birth records were generally not kept in Afghanistan and individuals would rarely be able to pinpoint the year of their birth.

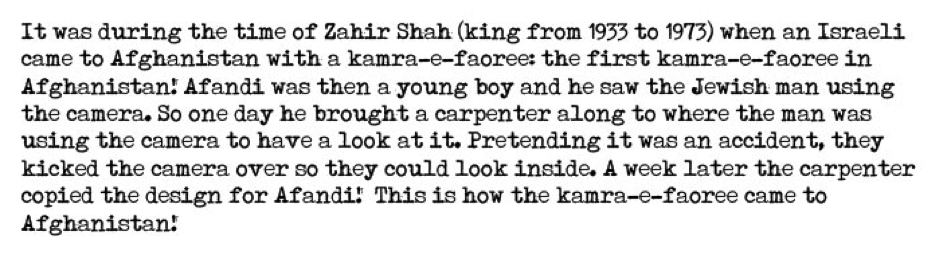

The teaming up of the kamra-e-faoree photographer with a scribe (the essential function of the accompanying official) can still be seen in Afghanistan today ? after an art. Beneath is a picture of Habibullah who has been a scribe for the past thirty years. He?s sitting on the opposite side of the street to where?Qalam Nabi used to work, the last working kamra-e-faoree photographer in Kabul. The man immediately to his left is also a scribe.

Lying beside Habibullah are a variety of forms with official stamps for various administrative purposes, and pens of different colours. Most of the forms require photographic identification as with this form Habibullah showed us below.

?

?

Scribes are a common sight in Kabul ? the fact that there is enough work to sustain them is likely connected to the very high illiteracy rates in Afghanistan, as well as the amount of bureaucracy.

It has, in fact, been the documentary requirements of this bureaucracy that has largely sustained box camera photographers in Afghanistan, at times providing them with windfalls of business. When the government of Hameed Karzai made it compulsory for all schoolchildren to be issued with yearly renewable identity cards after 2001, box camera photographers experienced a huge boom in business – fifty years after the initial surge of this photography.

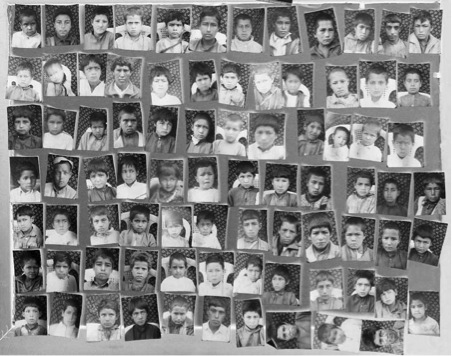

These images below are box camera photographs of school children taken by Ali Ahmad?in Herat and surrounds, and are from the collection of Hekmatyullah.

After 2001 girls schools were allowed to re-open (they were banned under the Taliban) thus adding even more to the business of box camera photographers, as can be seen below.

Courtesy of Ross McDonnell ?.

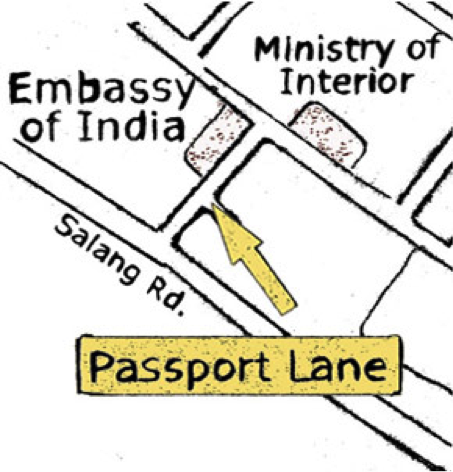

Traditionally, kamra-e-faoree photographers and scribes often clustered in the same places, such as in front of government ministries, courthouses and embassies – essentially where forms requiring photographic identification needed to be filled in. But kamra-e-faoree photographers also worked from busy chowks and street junctions, as well as directly outside of photo-studios in and around the city.

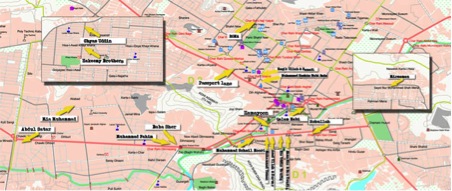

Here?s a map showing some of the photo-studios and street pitches where we found kamra-e-faoree photographers had been working in Kabul.

Many of the photographers we met owned their own photo-studio, though this was not necessarily the standard: it has to be said our interviews were more often with studio-owning kamra-e-faoree photographers because they were easier to locate than their street-based counterparts who didn’t have a studio to anchor themselves geographically (or financially for that matter, making it possibly more likely that street based photographers might drift into other types of work). If working from a studio the photographer often kept a kamra-e-faoree standing outside on the street. Inside the shop, they used a variety of cameras from 35mm cameras to large format cameras (which were also known as the ?’Indian camera’) to make individual and family portraits.

An image of Ahmad Zia Ansari using an large format camera in his photo-studio in Mazar-e-Sharif.

Clearly, many kamra-e-faoree photographers are versed in more types of photography than the kamra-e-faoree. Here are some of the old cameras we found the photographers had been using at one time or another in their careers. Taking photographs like these.

Polaroid film.? ?? ????????????????????????????135 colour negative film.?? ?????????Rollfilm with 6×6 camera.

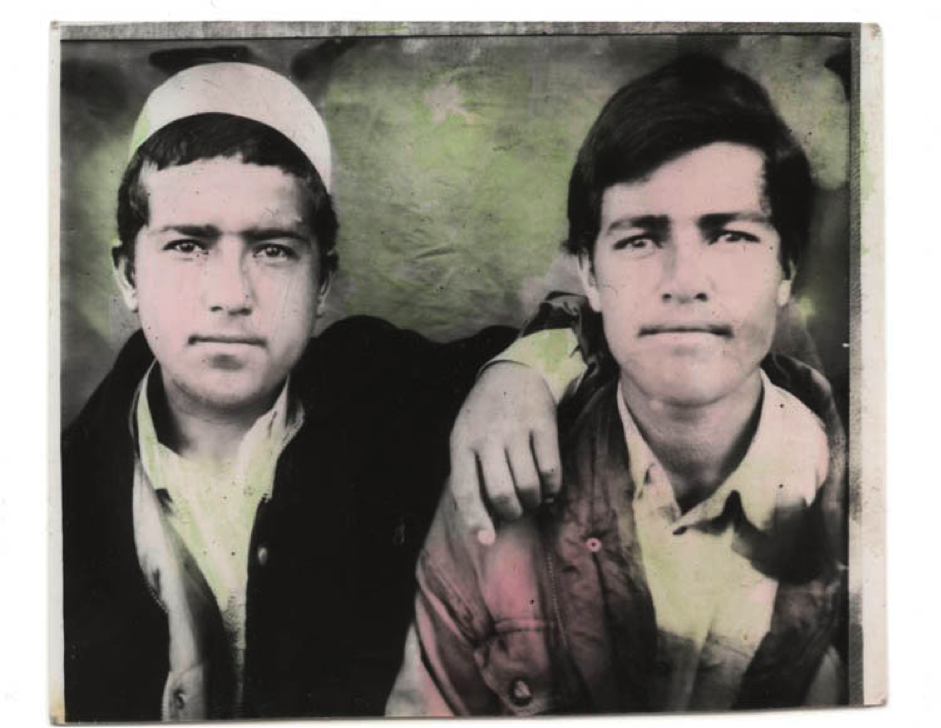

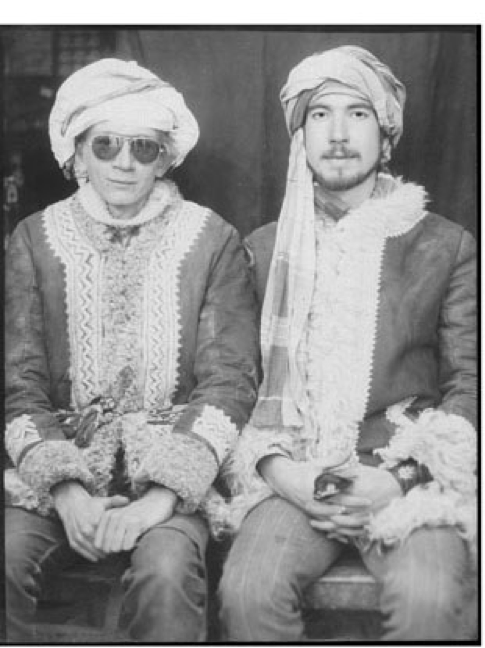

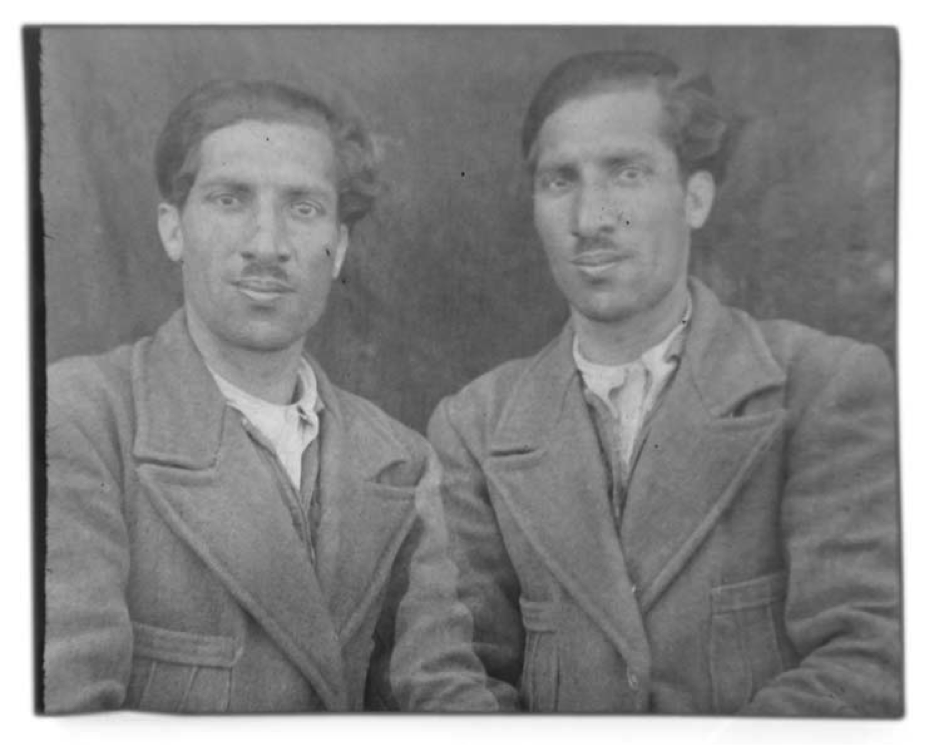

And being an adaptable craft it’s not surprising that the kamra-e-faoree has found more uses other than being used exclusively for identity photographs. Afghan clients sometimes obtained kamra-e-faoree photographs as mementos, having portraits made of themselves with friends and family, like this one below.

Passing foreign photographers, photojournalists and the odd tourist also had photos taken with the kamra-e-faoree. Here’s a box camera photograph of two Dutch tourists in Kunduz, Afghanistan taken in 1969.

Courtesy of Ewald Vanvugt/Collection International Institute of Social History,

Amsterdam, The Netherlands ?.

This photograph of a British tourist in Kabul was taken over thirty years later in 2006.

Courtesy of Adam K. Ashgar ?.

While some kamra-e-faoree photographers using techniques of montage and collage that are replicated widely in both earlier large format hand-coloured photography and contemporary Afghan digital photography, have turned the camera on their own families to thrilling effect.

This montage (from circa. 1950s) belongs to collection of Abdul Satar and is of his father. Naturally enough, he keeps it as a memento in his family album.

But any image, regardless of its original purpose, can be a memento.

In 1996, the photographer Fazal Sheikh traveled to Afghan refugee camps in northern Pakistan where he was told the stories of Afghans who had lost loved ones during the Soviet invasion and the subsequent civil war. Some of the refugees possessed photographs of those they had lost; some were taken with a kamra-e-faoree.

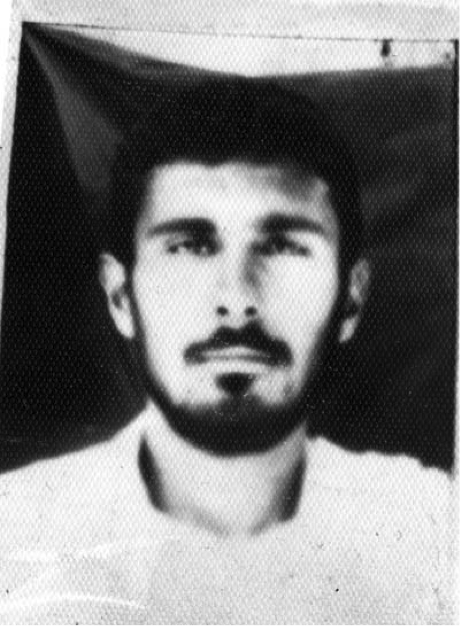

Below, Qurban Qul, one of the Afghans Fazal Sheikh met in northern Pakistan, holds a kamra-e-faoree photograph of her son Mullah Awar. He was killed fighting with the Mujahedin in 1986 when he was eighteen. Fazal Sheikh?s touching film The Victor Weeps can be seen here.

Courtesy of Fazal Sheikh ?.

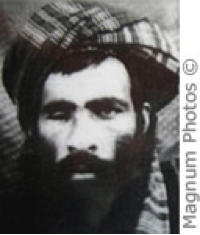

With war raging in Afghanistan since the Soviet invasion in 1979, colossal numbers of Afghans received war-related injuries. Sometimes they needed photographic proof of their injuries to claim benefits and medical attention from the clinics and organisations operating to help them. One such victim who lost an eye fighting against the Soviets was Mullah Omar, the present leader of the Taliban.

Here?s a kamra-e-faoree photograph of Mullah Omar from 1993 (verified by Pakistani intelligence).

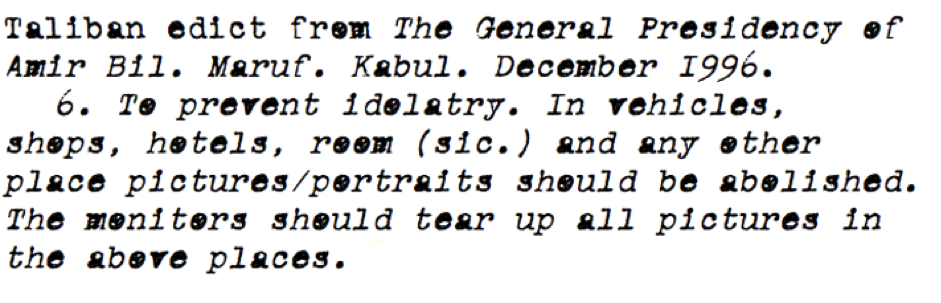

Mullah Omar?s (alleged) portrait may seem at odds with the commonly held view that the Taliban were fundamentally opposed to the depiction of the human (and animal) form – in any shape of manner. It certainly is at odds with the following Taliban edict from 1996 reprinted in? Ahmed Rashid?s book Taliban (Rashid by the way stressed that any typos which appeared in the list of decrees in his book were the Taliban?s and not his.)

However, kamra-e-faoree photographers were allowed to operate in Taliban controlled Afghanistan – even if, as the accounts we received testify, they at first met with beatings and intimidation until the Taliban finally relented allowing kamra-e-faoree photographers to work unhindered.

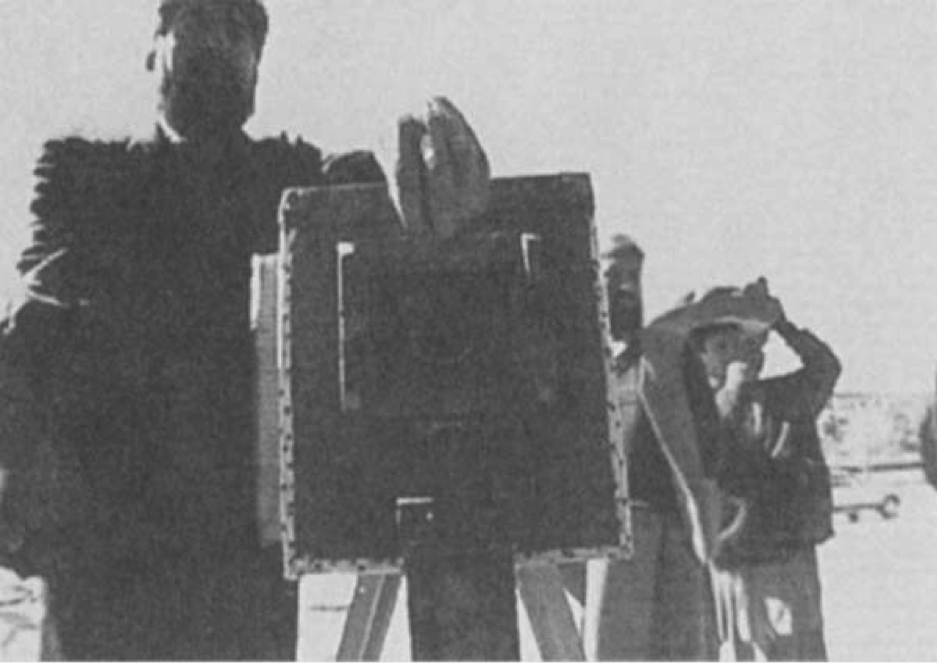

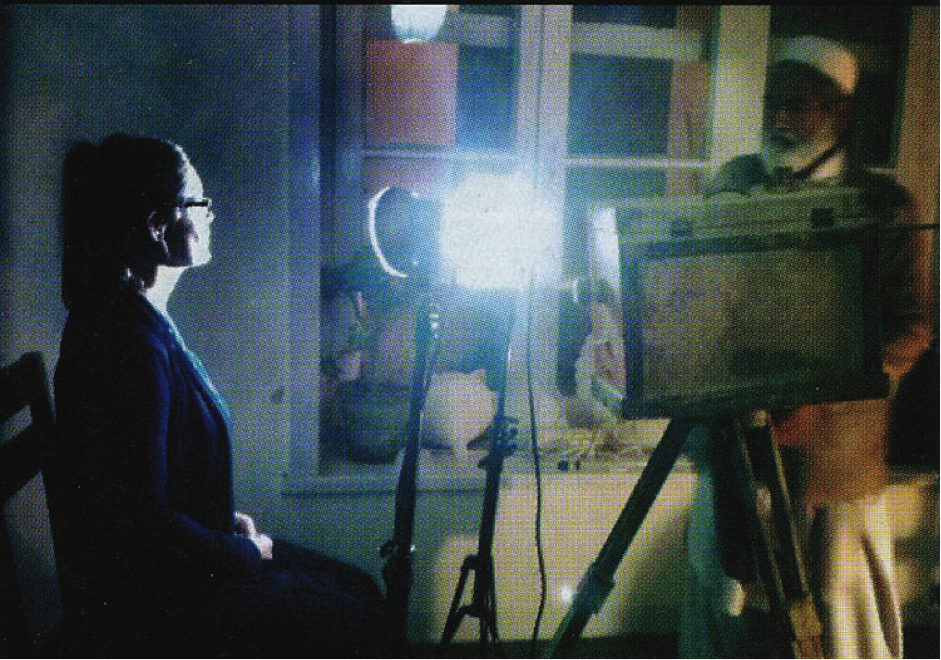

Here?s a picture of a kamra-e-faoree photographer taking a photograph in March 2000 during the Taliban-era in in Kabul.

Photo by Alan Edelstein published in Transition 2007.

The image is a frame-grab from the video camera of Alan Edelstein, an American film-maker, who was in an odd as well as precarious position whereby the Taliban had given him permission to carry a camera in the country but not to use it which they considered “unIslamic” ? but of course he did (surreptitiously).

Ultimately, the services of kamra-e-faoree photographers were needed by the Taliban to produce a variety of photographic identification ? sometimes for Taliban themselves. Indeed after their fall, files containing images of Taliban recruits were found in the Ministry of the Interior in Kabul.

It should be noted that the Taliban stance on photography was not necessarily the only or the greatest challenge to kamra-e-faoree photography. The infighting of various Mujahedin factions and warlords for control of the country after the Soviets left in 1989 reeked havoc in Afghanistan. Kabul was a major centre of the conflict and saw a brutal period of bombardment which at its height was estimated to have killed twenty-five thousand civilians.

Many photographers in Kabul had their studios destroyed or looted during this time. Those who survived and stayed on often lived in atrocious conditions.

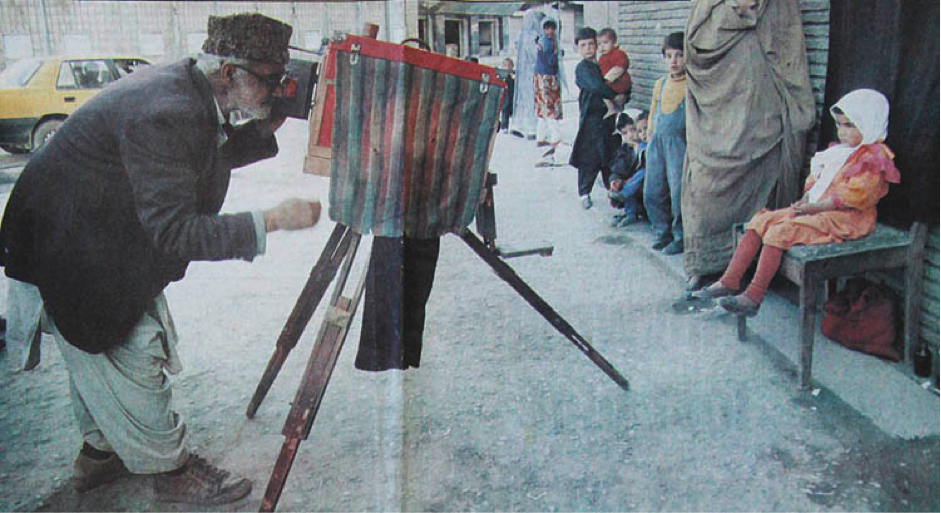

Though as the photograph below of photographer Ghulam Ahmad taking a picture of little Yaido testifies, life did continue. The photo was taken in Kabul in 1996 before the Taliban took control.

Photographed by Tony Ashby and published in the Western Australian 1996.

Since the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan by the United States of America and their allies, and the subsequent fall of the Taliban, there has been a huge increase in demand for photography in Kabul.

Reports suggest that kamra-e-faoree photography actually flourished in the years immediately following the invasion. Photo-studios too certainly wasted no time in cashing in on a demand for personal and family portraitures. But the last decade has also marked the beginning of the end for kamra-e-faoree photography; since 2006 in particular the numbers of photographers has dwindled so rapidly that by June 2011 there were only two kamra-e-faoree photographers working on a daily basis in Kabul. In 2012 there were none.

There are a number of reasons for this.

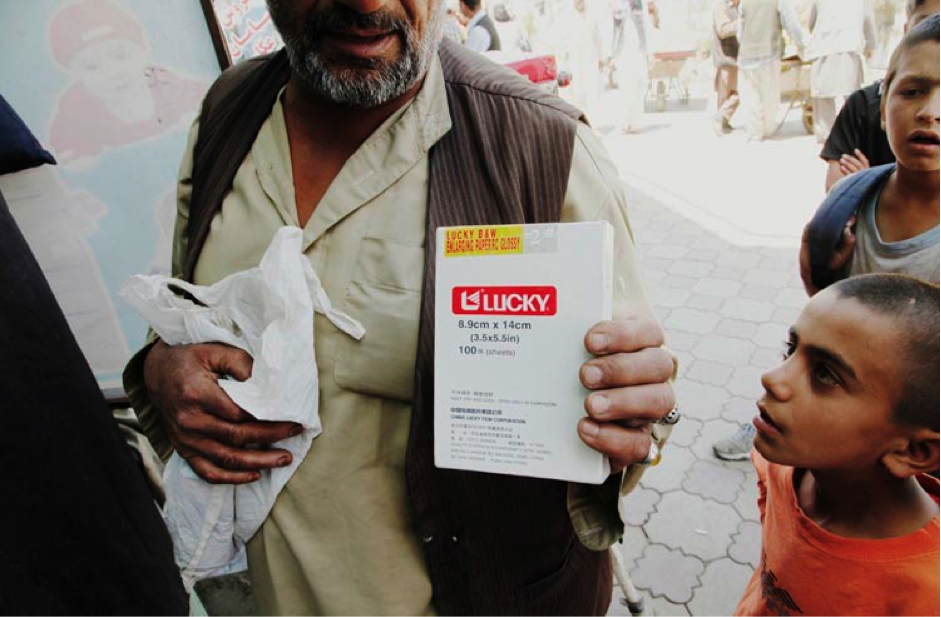

While the rapid rise of digital photography and the spread of modern photo-studios has played a major role in overshadowing the use of the camera, so too has the difficulty and expense in sourcing materials, particularly photographic paper and chemicals.

Here?s a picture from Rohullah, a Kabuli kamra-e-faoree photographer, in 2011; he?s holding one of his few remaining packets of?Lucky?photographic paper (a Chinese brand); Rohullah told us at the time that when his stock of paper runs out he would have to look for other work.

Within the year Rohullah had moved outside of Kabul to open a grocery store. His pitch had been taken over by a perfume seller, shown in the photo below.

Security has also been an issue.

Many box camera photographers worked in and around an area known as Passport Lane close to both the Indian Embassy and the Interior Ministry.

A photographer at work in Passport Lane, 2002. Scribes can be seen working in the background. Courtesy of Dave Banks ?.

Following bomb attacks targeting sites such as the Indian embassy in Kabul in 2007 and 2008, an increase in security measures has meant that many kamra-e-faoree photographers taking photographs intended for visa applications were denied access to their regular pitches in the area around Passport Lane. This is a pattern that has been replicated throughout the city.

Another reason for the decline of the kamra-e-faoree is that government offices began to demand colour identity photographs for official paperwork, and no longer accepted black and white photos. In addition authorities pursued a policy to clear the pavements of obstructions, which effected street vendors of all kinds (see Muhammad Isaq’s portfolio).

Another reason for the decline of the kamra-e-faoree is that government offices began to demand colour identity photographs for official paperwork, and no longer accepted black and white photos. In addition authorities pursued a policy to clear the pavements of obstructions, which effected street vendors of all kinds (see Muhammad Isaq’s portfolio).

Nowadays, kamra-e-faoree ? or rather defunct examples of the kamra-e-faoree – play another role on the streets of Afghanistan: advertising the services of photo-studios and digital photographers. In a country where the illiteracy rate is so high, visual indicators displaying commonly-used services are important, or as one shop owner put it:? ?For the village people, because they can?t read.?

The Ariana Studio in Kabul is one such case, located between a tea shop and a hamam (bathhouse).

In Mazar-e-Sharif we found the kamra-e-faoree more widespread as a service-advertisement than in Kabul. Here?s a picture of an old kamra-e-faoree from outside the Tagin Photo Studio in Mazar-e-Sharif. Photocopy is written on the side, advertising photocopying services inside the studio.

Many of the kamra-e-faoree in Mazar-e-Sharif were also noticeably smaller than those in Kabul. Below: a compact kamra-e-faoree outside Zia Uddin?s photo-studio in Mazar-e-Sharif.

While some of the studios even build cheap mock-ups of the kamra-e-faoree, as can be seen from the model camera outside Saif Fardin’s Photo Studio in Mazar-e-Sharif.

Photo-studios in Afghanistan are at present almost exclusively digital. The services they offer include the digital manipulation of old kamra-e-faoree photographs which customers bring to get restored, repaired, enlarged and sometimes coloured: it’s where kamra-e-faoree meets the computer software?Photoshop. This is a short video of Asad Ullah reworking an old box camera photograph on his computer.

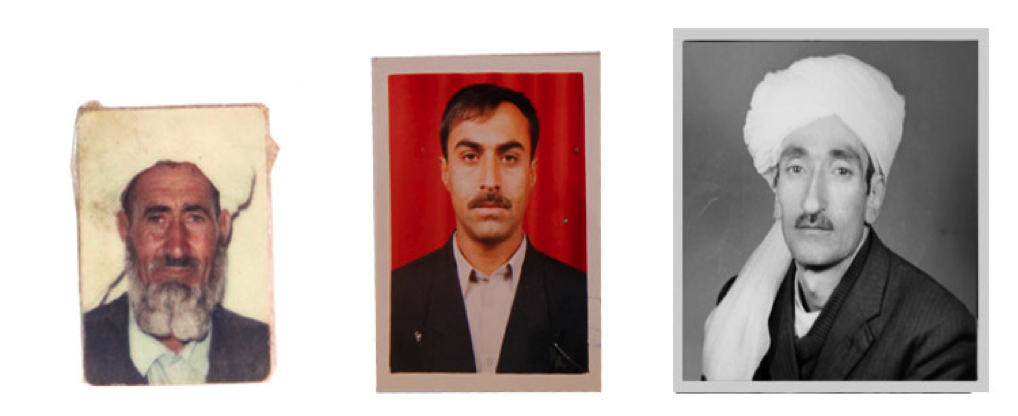

The majority of the subjects in these photographs are deceased; they are the relatives of Asad Ullah’s costumers who have brought them to be repaired. The gallery below is composed of more of these photoshopped images.

At the same time as using the box camera, kamra-e-faoree photographers adopted digital technology. Hanging above Qalam Nabi?s kamra-e-faoree in 2011 a sign advertised his secondary enterprise.

Electronic photographs.

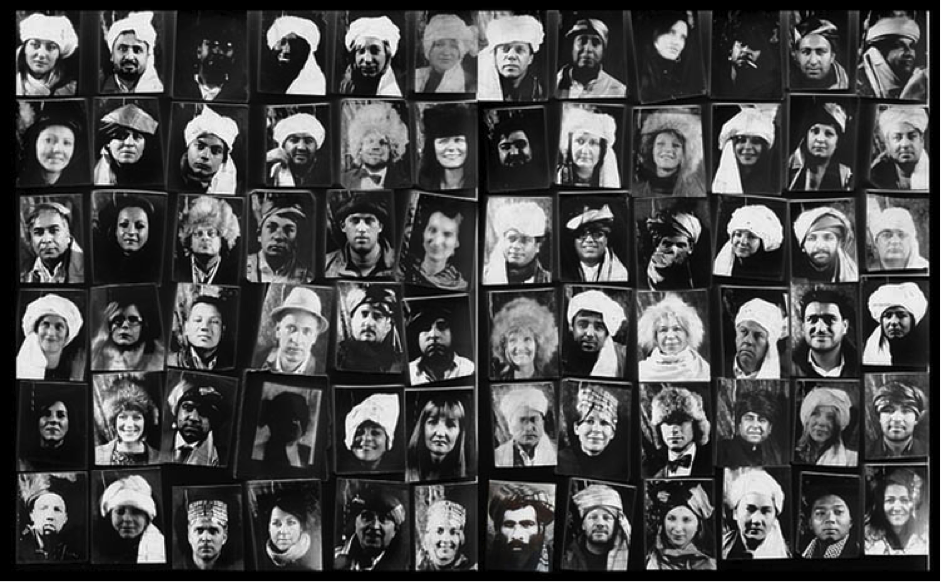

A contemporary rebirth of the kamra-e-faoree as seen at least on one photo-journalism course in the capital has been to teach Afghan students the basics of photography, before tackling the use of digital cameras. The course was organised by the media organisation AINA in Kabul.

.? AINA

Many kamra-e-faoree have also found their way into the hands of the large international community in Afghanistan who purchase them as a quintessential Afghan souvenir of their stay. Here?s a French expat in Kabul in 2011 learning how to use the kamra-e-faoree. He just bought the camera and it?s his very first time peering through it.

Some foreigners immerse themselves in the camera. Below are images from Aur?lien de Saint Andr? and Molly de Saint Andr??s photographic odyssey between Afghanistan and France with a kamra-e-faoree. Aur?lien can be seen photographing two policemen on the Greek-Albanian border; directly beside this is the resulting positive image, which Aur?lien has made by digitally photographing the negative and inverting it on his computer.

Courtesy by Aur?lien de Saint Andr? and Molly de Saint Andr? ?.

And a wonderfully symbolic picture of Landry Dunand, another French national, cycling through the streets of Kabul on a summer?s night in 2010 shouldering a newly acquired kamra-e-faoree which is destined to exit Afghanistan.

Courtesy by Landry Dunand ?.

Some expatriates living in Kabul have hired kamra-e-faoree photographers to take portraits at farewell parties. The image below shows?Mirzaman?taking a box camera photograph at an expat farewell party in 2012. It was the first time he took box camera with artificial lighting – and he says all went well.

Source: Afghan Scene.

The box camera photographs below were taken at the ‘Retreat from Kabul’ farewell party of journalist Jerome Starkey and companions who were leaving Afghanistan after four to five years residence.

Courtesy of Jerome Starkey ?.

To finish up, here are some stills of?Qalam Nabi, one of the last kamra-e-faoree photographers in Kabul, working from the same street pitch that he worked from all of his life, and his father before him.?

In May 2012, according to reports, Qalam Nabi had gone to London to look for work.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.