Subscribe to ShahidulNews

by rahnuma ahmed

A vicious cyclone had struck the night before. Dawn, stillness. A calm and eerie light. I tagged behind my older brothers as they ventured out, gazing in awe at a neighbouring house, its roof had flown off, while scenes of devastation lay around us with trees uprooted, branches severed from trunks, debris lying in the middle of the road. Fragments of a childhood memory.

As news of death and destruction poured into our home, so did groups of radio artists?singers, musicians?and many others, all working for the Chittagong radio station, like my father, a journalist, who worked in its news section.

By midday we were out in the streets, singers and musicians at the front, the rest behind, two rows of men, women and children, holding on to the corners and edges of a white billowing bedsheet. As the long procession wound down major roads, pedestrians turned around at the sound of singing, reaching for their pockets as we drew nearer. Women and girls peered at us, while boys were sent out, clutching notes, or a handful of coins (in those days, coins mattered). As the hours passed, the chador no longer remained taut; heavy with cash offerings, it sagged in the middle.

We trooped home. Instructed to separate coins from banknotes, we kids worked feverishly as my mother busied herself in rustling up some food for the sudden influx of guests. Neatly laid out piles of banknotes, tottering columns of coins. My father and his colleagues counted, double-checked. The money was sent off to aid cyclone victims. It was 1965. It was Chittagong. We belonged to Pakistan.

The central seat of power, Islamabad, was far away. It was (still) possible for state functionaries and artists to come together. To take to the streeets spontaneously, aroused by community feelings of helping people in distress. An event that was not orchestrated. No heads had rolled. Had cameras clicked? No, not that I remember.

Fast forward to now. Natural disasters. Large cheques are donated to the prime minister’s relief fund. Banks. Multinational mobile phone companies. Business associations. Civil society. NGOs. Smaller cheques too, a day’s salary of government employees, of private firms. An extended hand offers a cheque, as the other accepts, both faces turn toward the TV cameras, toward the photojournalists. The state-capital-media nexus, although riven by internal disagreements and rivalries, work collectively to manufacture national interests. A far cry from earlier times when broadcasting and telecasting space was controlled by state-owned Radio Bangladesh and Bangladesh Television, when 5-10 regular privately owned dailies, and a film industry, not known for signs of originality, was all that there was. Before things began changing in the 1990s.

Market reforms however, began earlier, Ziaur Rahman (1975-1981) and Hussain Mohammad Ershad (1981-1990) used them as instruments to build and maintain political coalitions, particularly with traders and industrialists. Economic liberalisation programmes, traded off for garnering the political support of business elites, did not, as Fahimul Quadir points out, contribute to the micromanagement of the economy, nor to the advancement of human development goals.?Instead, they allowed big business to emerge as a major player in national decision-making. Not unsurprisingly, contradictions emerged?it adversely affected the state’s ability to enforce contracts, to develop a mechanism for redistributing assets?but these were ignored by the military rulers as the issue of gaining legitimacy among civilian sectors was far more pressing.

Despite General Ershad being ousted from power in 1990, subsequent regimes, led by Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina, treaded earlier paths, smoothed by undisclosed contributions to party coffers, far more important than improving the living standards of the majority. These patterns are similar to those in Philippines, president Marcos, US ally and long-time friend, was deposed in 1986 through a popular uprising, but despite his ouster, many, if not most, of the “fundamental relations of exploitation,” remained intact. Democracy was “nominally restored” while the masses continued to suffer, writes Jonathan Beller; prostituted Filipinas became overseas Filipino workers (OFWs), radicals continued to be murdered, giving lie to a particular fantasy about the importance of individuals (autocrats are deposed, but the system does not get dismantled).

Ceaseless political party bickering which has characterised politics in Bangladesh for the last two decades, has benefited media corporatisation’s ideology, “impartial” and “neutral” news journalism has been redefined as that which is independent of political party allegiances, distracting attention from the fact that corporate media works to further corporate interests, to create a consumer culture, to advance the interests of market forces (Fahmidul Huq). Not surprisingly, there have been other contradictions as well. As Zeenat Huda Wahid notes, Khaleda Zia’s new media policy in 1992 initiated satellite television, leading to scores of Indian channels being available to Bangladeshi viewers. Despite, Huda argues, the BNP government’s crafting of a religio-territorial identity, one that was portrayed as resistant to Indian domination. ?Or, as Meghna Guhathakurta writes (1997), Sonar Bangla, the rallying cry of the liberation struggle?evoking images of classlessness, prosperity, peaceful agrarian relations?was not only abandoned by the Awami League post-1971, it has become “fossilised.” Sheikh Hasina’s government (1996-2001; 2008 onwards) has not veered from liberalisation policies initiated by previous governments, including those which are her sworn enemies, the BNP-Jamaat alliance that ruled the nation (2001-2007); the present government’s proclamation of Muktijuddher pokkher shokti is shorn of Shonar Bangla ideals, as fundamental relations of exploitation remain. Intact.

The culture industry’s victory lies in two things, “what it destroys as truth outside its sphere can be reproduced indefinitely within it as lies.” We can no longer simply talk of control, writes Sefik Seki Tatlic, we must talk of the nature of the interaction between one who is being controlled and the one who controls.?Of how the one that is “controlled” is asking for more control over him/herself while expecting to be compensated by a surplus of freedom to satisfy trivial needs and wishes. Of how the fulfillment of trivial needs is declared as freedom. Readers, remember, RC Cola, freedom of choice? Or, remember Grameen Phone’s current slogan, Stay Close, invoking family ideology (security, warmth, intimacy, support, romance) to further corporate profits (Stay Close so that we can fleece you?). Consumer freedom, Tatlic reminds us, implies as well the freedom to choose not to be engaged in any kind of socially sensible or politically articulated struggle. Very true in the case of Bangladesh, for one does not see media celebrities, singers, actors and actresses, writers, playwrights, intellectuals, advertising industry’s geniuses etc etc, those who froth at the mouth at the slightest mention of 1971, lend support to any of the pro-people struggles and movements current in Bangladesh, two of the foremost being the garments workers struggles for living wages and safe and secure workplaces, ?and, the Phulbari peoples struggle to not be uprooted from their land and livelihood, to resist the impoverishment which multinationals, and the government (both present and past) have destined for them.?Life is so much more comfortable for the ruling class and its functionaries when Muktijuddho gets divested of Shonar Bangla ideals, when fundamental relations of exploitation can, and do, remain intact.

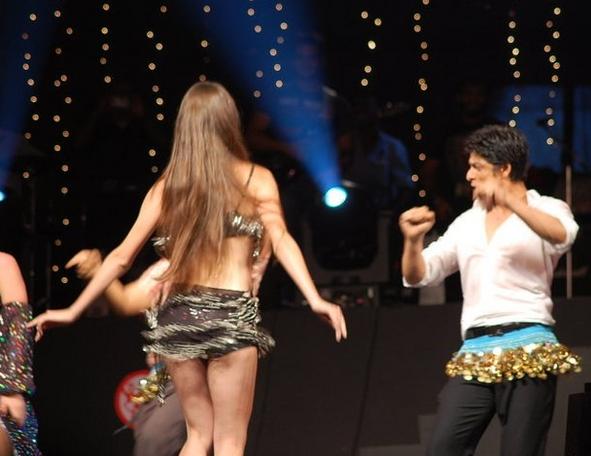

The category of the “spectacle” is the medialogical paradigm, says Beller, as the accumulation of capital becomes an image (think of all the commodities advertised), and again, as “the diplomatic presentation of hierarchical society to itself.” The spectacle is not merely a relation, but a relation of production for it produces consciousness. We must put language on images, he writes. Excited by Beller’s theory, I return to YouTube to watch Shahrukh Khan’s performance in Dhaka (I missed when it was shown live on TV), where Dhaka crowds, who had paid exorbitant amounts to purchase tickets, were said to have been bowled-over by the mega-star’s performance.?A few voices have expressed their disgust at the “vulgarism,” ?at the “obscenity,” at his cultural arrogance, his condescending attitude toward the Bangladeshi audience, at his oft-repeated use of a “slang” word (not written by those who felt offended, I had to go to great trouble to discover it). Shala! Now, shala is a kinship term, used by the husband to indicate his wife’s brother. Gentrification has led to `shaylok‘ being preferred over shala, and I have yet to find a Bengali able to explain why it offends. The answer lies in its underlying message, embedded in patriarchal power relations, deeply sexualised, “I f..k your sister.”

The diplomatic presentation of hierarchical relations between India and Bangladesh as the BSF, the Indian border forces, kill Bangladeshis randomly, systematically? The King Khan tamasha made us forget the truth that lies outside the sphere crafted by the culture industries. Shala is a patriarchal lie, it must be dismantled.

Published in New Age, Monday February 21, 2011

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.