by rahnuma ahmed

Its been a bit over a decade since I left Jahangirnagar to become a fulltime writer, but I discovered soon after that no one really leaves Jahangirnagar. I’m still as attached to the place as I’d been when I was a faculty member. For good reasons too, for, when push comes to shove, one is bound to encounter a group of teachers and students, who, however powerful be the forces they are up against, however fractured they themselves might be, are willing to overlook ideological differences or personal rancour, to forge together a collective front. To protest, in order to reclaim JU as a place of higher learning and academic dissent, one where women students too, have equal claims to freedom of movement and association, free from sexual harassment and intimidation. A campus which, like its open and unfolding landscape, nurtures diversity and tolerance, nourishes the creation and re-creation of cultural inventiveness.

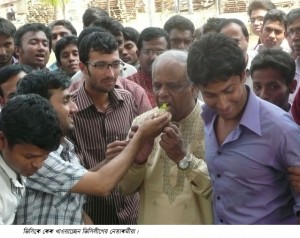

That is the spirit of Jahangirnagar, one that has been badly bruised by more than three years of having been led by Sharif Enamul Kabir, professor of chemistry, who was appointed vice-chancellor in February 2009 after the Awami League-led grand alliance swept into power.

Goratei golod, for, professor Sharif’s appointment as vice-chancellor was in contravention to the JU Act, 1973, passed by the first parliament of independent Bangladesh (which repealed the Jahangirnagar Muslim University Ordinance, 1970, under which JU had been established by the government of Pakistan in 1970). The 1973 Act states:

“Section 11. (1) The Vice-Chancellor shall be appointed by the Chancellor for a period of four years from a panel of three persons to be nominated by the Senate on such terms and conditions as may be determined by the Chancellor, and shall be eligible for re-appointment for a further period of four years” (The Jahangirnagar University Act, 1973).

In professor Kabir’s case, there was no panel; in other words, there was “selection,” no “election.” But that is not why JU teachers, who united under the banner of Shikkhok Shomaj (Teachers Society) in December last year, have begun demanding the vice-chancellor’s resignation. If that had been the case, i.e., his irregular appointment alone, they’d surely have raised their voices three years ago.

In other words, no one can accuse Shikkhok Shomaj of having jumped the gun. Of having deliberately disrupted peace and stability on campus. Of being driven by ulterior motive. Of being maliciously inclined.

Which is precisely what the vice-chancellor and his supporting cast of academics are doing — the Shikkhok Shomaj’s 8-point demands are “illogical,” they are “hampering the education atmosphere,” teacher agitation is motivated by a bid for “personal” gain — but these allegations don’t stick. Especially not after Zubair Ahmed’s killing.

Its brutality defies all modicum of humanity. I have read and re-read newspaper accounts, only to sit and stare at the screen blankly. What is there to add after one learns from press reports that he had been taken to a secluded place near the Teacher Students Centre, close to the house of a faculty member (see blogger Abid Azad’s account, A Political Prey, January 20, 2012). That he had been beaten by pipes and iron rods for an hour, that blood had gushed out as the rods had gone through his body (Faruk Wasif, Prothom Alo, January 17, 2012).

Campus security guards claim, they heard no screams or cries. The security officer Ajimuddin, was suspended. That is the official version. He has actually been transferred and reinstated in the estate department. No show cause notice served on him for having failed in the performance of his duty. For having failed to secure the life of a student. Instead, he gets away by saying, he too, is “shocked.” He too, is “angry.”

According to police sources, Zubair was taken from campus to the Enam Medical College Hospital in Savar in an auto rickshaw, and left at the hospital gates. But hospital security guards who’d been on duty say, no, no injured person had been brought to the hospital in a vehicle. So, what had happened? Who took him to the hospital? Was he still in his senses then?

According to press reports, his girlfriend received a phone call that evening. Someone you know is in Enam Hospital. Zubair’s friends had rushed to the Enam Hospital. The doctor on duty helplessly suggested they take him to Dhaka. They did. He was admitted to the United Hospital at 10pm. He died in the early hours of dawn, the next day.

Why? I mean why did he have to die?

The answer can only be a single “no.” Because, he didn’t have to.

Zubair too, was a member of the Bangladesh Chatra League. But he had belonged to the other faction, the one which reportedly doesn’t enjoy the vice-chancellor’s patronage. To the Shafin-Shammo group, which was suspended from JU for 2 years after having allegedly participated in BCL factional clashes on July 5, 2010, when rival members had been thrown off the roof of the Al-Beruni dormitory. When a member of the ruling party had tartly remarked, if they had to, why couldn’t it have been a member of the opposition students group instead.

Over twenty violent clashes in the last 3 years. Enquiry committees, members mostly belong to the VC group, reports not released. Officially-speaking, no committee of the BCL exists on campus. In reality, it does. The media call it the “VC League.” Activists belonging to the latter control seat distribution, tender manipulation, extortion, mugging (Daily Star, January 11, 2012). The proctor — forced to resign because of student protests after Zubair’s killing — had accompanied armed “VC League” members to regain control of Bangabandhu Hall (Kaler Kantho, January 1, 2011).

The BCL’s central committee has no control over this League, as it is run by the vice-chancellor himself. The Godfather.

Published in New Age, Monday, April 2, 2012

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.