by rahnuma ahmed

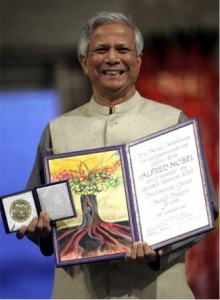

Dr. Muhammad Yunus, proud recipient of The Nobel Peace Prize, 2006, which was awarded jointly to Muhammad Yunus and Grameen Bank, which he founded, “for their efforts to create economic and social development from below.”

I had written earlier in this series that now, when I look back, it seems that the policy planners of the consortium government had almost arithmetically calculated that a ‘political vacuum’ resulting from minus-ing the two leaders, from dismantling the organisational structure of the two major political parties — would create the enabling conditions for redrawing the terrain of politics in Bangladesh (divorcing it further from the issue of national sovereignty) in a manner so as to serve, and further perpetuate, the interests represented by the western power bloc.

(Apparently, our leading politicians, bogged down as they are in personal feuding, and a politics of bloodletting, murder and mayhem, are not sufficiently geared towards serving the cause of imperial interests. This, in itself, is an interesting idea, because imperial interests have been suitably served by creating, and stoking, precisely such a chain of events, popularly known as the colonial policies of “divide and rule.” For instance, the Shia-Sunni sectarian conflict, which was unknown in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq).

Further, that if a person with the requisite status and charisma were to be introduced on the political landscape, he would easily, almost automatically be able to fill the vacuum in political leadership. That, he would easily, almost automatically be able to win the hearts and minds of the voters, who were badly bruised from two decades of political instability (at times, crippling), and, from the politics of murder and mayhem. That, he would be able to form a political party which would gain broad layers of support from the people, that this was likely to lead to a sweeping victory in national-level elections (I had also mentioned a fallback plan of forming a national unity government, composed of a coalition of civil-military bureacrats, technocrats, business and political elites, but that is a seperate discussion).

I had written that Dr. Muhammad Yunus’ winning of the Nobel Peace Prize (August 13, 2006), and his subsequent declaration of wanting to enter national-level politics (February 11, 2007), could not have occurred at a more opportune moment from the consortium planners’ point of view.

Dr Yunus’ endorsement of the actions taken by president Iajuddin, at a grand reception accorded by the latter in honour of his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize — “You will have to take a tough line ignoring the criticism and prove your point right” (Daily Star, November 6, 2007) — could only have helped to create general dismay (bordering on incredulity?), as the “only” point that president Iajuddin was then proving “right” was nothing else but dragging his feet, and very slowly too, to ensure that he, in addition to being the president, remained the chief advisor to the caretaker government (a power ‘grab’ which had betrayed the spirit of the principles of caretaker government as enunicated in the constitutional amendment), so that a BNP-Jamaat election win could be ‘fixed’.

Many members of the shusheel shomaj expressed relief at Dr Yunus’ decision to join active politics, to launch Nagorik Shakti which, as he’d announced, would contest elections from all 300 constituencies. Since he was not a politician, so they argued, he was unbesmirched by political corruption; only a leader of his calibre, could lift the nation out of the deep political morass, could take the nation forward. Nagorik Shakti’s slogan Bangladesh Egie Cholo (Bangladesh Go Forward) expressed it well; as a political slogan it captured, and capitalised, as it were on the spirit of the times. Innumerable TV commercials, selling consumer items ranging from mobile phones to soft drinks, had drawn on this theme, as had corporate ads for the Bangladesh cricket team, designed at forging solidarity sentiments which would inspire it to win regional and international matches.

I would now like to turn to the issue of NGOs, one of the reasons being that among the shusheel shomaj, NGOs are the chief institutionally organised force; and, secondly, because although the Grameen Bank — founded by Dr Yunus (and, the co-winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize) — is technically not an NGO (it is a bank), but it is regarded as such both at home and abroad, because of subscribing to development theory and ethos, approach, expertise, networks of national and international partnership etc., etc.

The significance of NGOs in Bangladesh has, in recent years, attracted the critical attention of scholars, both those who are from Bangladesh, and others, from abroad. They have all insisted on placing it within the larger context of post-cold war politics and the rise of a market-biased neo-liberal ideology which de-emphasises the role of the state, emphasising instead the role of non-state actors such as private capital and NGOs (M. Shamsul Huq, International Political Science Review, 2002). Some authors have drawn our attention to official donor policy of the mid-1980s, when funds began to be channeled to local NGOs, a policy also known as the “civil society empowerment,” or “rolling back the state” approach. Interestingly enough, one such study of Bangladesh is titled Civil Society By Design (2002), and the author, Kendall Stiles, argues that although the intermeshing of development agencies and institutions

— embassies and missions of multilateral and bilateral donors, local offices of international relief agencies, and indigenous NGOs — might be considered as beneficial, as being a “tool of social progress” since their potential to “do much good” exists, but in the long run, they may, even through performing socially beneficial activities “undermine a country’s independence and self-determination.”

As part of “rolling back the state,” foreign donors or aid agencies have increasingly portrayed NGOs as the means of democratisation; as a means for reducing the authoritarian tendencies of the government; as a substitute for inefficient and corrupt government; as a means of increasing social and political awareness among the citizenry; of reducing poverty (micro-credit); of empowering women socially, economically and politically through organising them; and, of empowering ethnic minorities as well, who are socially and culturally marginalised by the ethnic majority.

Local NGOs in third world nations have increased their power and influence by establishing partnerships with foreign NGOS, such as, Oxfam, World Vision, Save the Children, Greenpeace, Interparliamentary Union, Amnesty International, and Transparency International. Many bilateral agencies, these include, DFID (British), Canadian International Development Agency, Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, Netherlands Organization for International Development Cooperation, and Danish Agency for Development Assistance, prefer to work with local NGOs in lieu of government departments and agencies.

The current trend, writes Haque, of replacing the obligations and responsibilities of government with those of development NGOs, has given rise to deeper concerns that the “social contract” between the state and its citizens is being “rewritten due to the expanded role of NGOs replacing the state’s obligation to deliver service.” That the citizens “entitlement” to basic services which are now increasingly being provided by development NGOs, for instance, educational, health and legal aid services, has led to, on the one hand, NGOs becoming a “shadow government,” and, more alarmingly, since the NGOs “enjoy almost complete autonomy from the people who rely on their services” — an increased lack of public accountability. This has been further accentuated by the dominance of their “charismatic founding leaders,” and practices, such as: staff recruitment based on the personal preferences and networks of these leaders, nepotism and loyalty as criteria for staff appraisal and promotion, centralised structure of management, lack of participatory decision-making.

In comparison to state agencies, development NGOs often enjoy a more positive image, because of the programmes that they undertake (education, training); they are more likely to be perceived as being more modern, more in tune with the changing times, and far more tolerant of social and cultural differences than the state and its functionaries. Recognising them as development partners has conferred legitimacy on their programmes and activities. The situation in Bangladesh has been made more complex, writes Haque, by the entry of NGOs in financial transactions and by taking over various profit-making economic enterprises: Brac (printing press, cold storage, garment manufacturing, retail outlets, and milk products), Grameen Bank and Proshika (banking, garments, shopping complexes, telephone systems, transport services, cold storage, fisheries projects, fertilizers, deep tubewells, and biotechnology). And secondly, their international recognition — Grameen’s micro-credit prgramme, Brac’s model for development, and its replication in other southern countries. The increase in the power of the development NGOs in relation to the government, and their worldwide recognition and replication has meant that often, Bangladeshi NGOs are “more influential” and have greater “international legitimacy” than that enjoyed by the government.

It is all true. And, it is only through recognising it as true that I can understand the shusheel shomaj/consortium’s eager appreciation of Dr Yunus’ decision to form Nagorik Shakti and to contest the parliamentary elections. Dr Yunus, however, changed his mind later (May 3, 2007), it seems due to a lack of popular support for his initiative. But isn’t this amazing given that the recognition which he had received was nothing small, or halfway, but the highest possible international recognition which a person can possibly get? It sets me wondering. Does it mean that the jubilation and euphoria among the educated middle classes at home, and among large sections of the international community abroad for having gone against prevalent conventions, for having insisted on being a “banker to the poor” — cannot be generalised? Does it mean that international recognition and the resulting charisma that it confers, cannot be translated into political capital, at least, not among the common people? Not even, after the application of considerable coercive powers to create favorable conditions? Does it also mean that the power, authority and influence of national NGOs as a collective force, strengthened enormously by international bodies, foreign donors and bilateral agencies, is as not as hegemonic as the consortium had hoped? Does it mean that the consortium was wrong in its calculations?

Does it mean that despite development NGOs being, at times, more influential than the government itself, for the common people, only political parties possess the potential for realising popular expectations and aspirations? That, the common people insist on having a say in how, and to serve whose interests, the government will be run.

If that is the case, then there is still hope.

Published in New Age, Friday, March 2, 2012.

Part VII

Part VI

Part IV

Part III

Part II

Part I

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.