by rahnuma ahmed

Drifting in cage and out again

Hark unknown bird does fly

Shackles of my heart

If my arms could entwine

With them I would thee bind

— Fakir Lalon Shah, ?Khachar bhitor ochin pakhi,?

translation by Shahidul Alam.

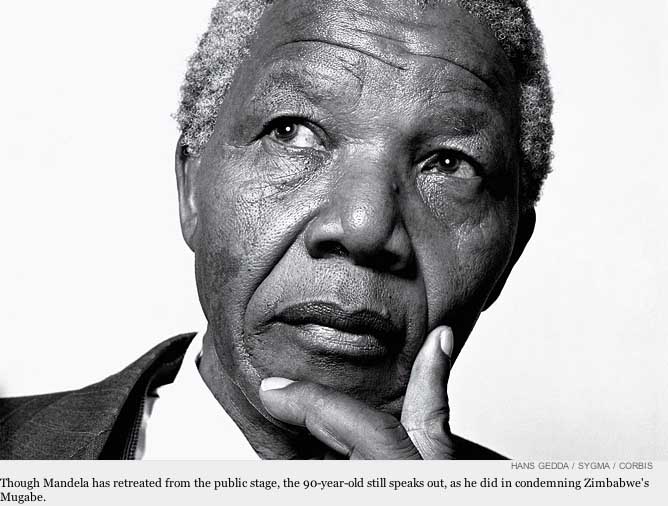

Baul sculpture, and the nation’s most powerful man

‘No decision is taken without the the army chief’s consent, that’s why we informed him,’ said Maulana Noor Hossain Noorani, amir of Khatme Nabuwat Andolon Bangladesh and imam of Fayedabad mosque, at a press conference. `He didn’t like the idea of setting up an idol either, right in front of the airport, so close to the Haji camp. It was removed at his initiative’ (Prothom Alo, 17 October).

The `it’ in question was a piece of sculpture, of five Baul mystics and singers. Titled Unknown Bird in a Cage, it was being created in front of Zia International Airport, Dhaka. Madrasa students and masjid imams of adjoining areas were mobilised, Bimanbondor Golchottor Murti Protirodh Committee (Committee to Resist Idols at Airport Roundabout) was formed. A 24 hour ultimatum was given. The art work, nearly seventy percent complete, was removed by employees of the Roads and Highways Department, and Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh.

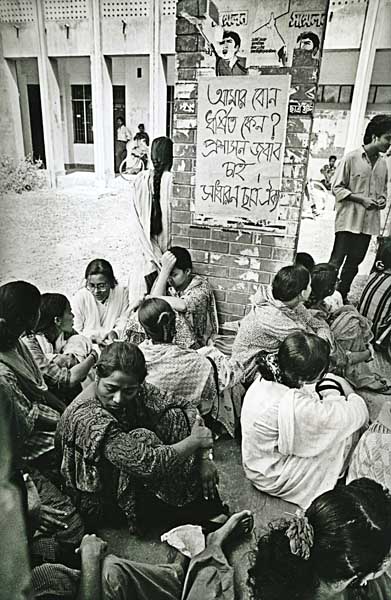

Artists, intellectuals, cultural activists, writers, teachers, students, and many others have since continuously protested the removal of the sculpture, both in Dhaka, and other cities and towns of Bangladesh. They have demanded its restoration, have re-named the roundabout Lalon Chottor, and accused the military-backed caretaker government of capitulating, yet again, to the demands of Islamic extremists, and forces opposing the 1971 war of liberation.

Soon after its removal, Fazlul Haq Amini, Chairman of a faction of Islami Oikya Jote (IOJ) and amir of Islami Ain Bastabayan Committee (IABC) said at a press conference, if an Islamic government comes to power, all statues built by Sheikh Hasina’s government (1996-2001) will be demolished, since statues are `dangerously anti-Islamic’. Eternal flames, Shikha Chironton (Liberation War Museum), and Shikha Anirban (Dhaka Cantonment) will be extinguished. Paying respect to fire is the same as worshipping fire.’ What about statues built during Khaleda Zia-led four party alliance government (of which he had been a part). ‘Where, which ones?’ Rajshahi University campus was the prompt reply. `Why didn’t you raise these questions when you were in power?’ ‘We did, personally, but they didn’t listen. We were used as stepping stones.’ Amini also demanded that the National Women Development Policy 2008, shelved this year after protests by a section of Muslim clerics and some Islamic parties, should be scrapped (Prothom Alo, 18 October).

Noorani and his followers demand, a haj minar should be built instead, and the road should be re-named Haj road. ‘Men from the administration and the intelligence agencies,’ he said at the press conference, `wore off their shoes, they kept coming to us.’ (Prothom Alo, 17 October). Now where had I read of close contacts between Khatme Nabuwat and the intelligence agencies?

I remembered. A Human Rights Watch report, Bangladesh: Breach of Faith (2005) had stated that KN had close links to the ruling BNP through the Jamaat-e-Islami and the IOJ, its coalition partners. I remembered other things too. It was the same Noor Hossain Noorani who had said, Tareq Zia, Senior Secretary General of the BNP, was their “Amir and same-aged friend,” and had threatened police officials saying Tareq would directly intervene if Khatme Nabuwat’s anti-Ahmadiya campaign was obstructed. According to reports, highup intelligence agency officials (DGFI, NSI) had mediated contacts between the ruling party and the KN. He had met the DGFI chief in Dhaka cantonment thrice, Noorani had thus boasted to Satkhira reporters in 2005, a statement never publicly refuted by the intelligence agency (Tasneem Khalil, The Prince of Bogra, Forum, April 2007, issue withdrawn, article available on the internet).

What links does the present military-backed caretaker government, and more so, its intelligence agencies, have with these extremist groups? I cannot help but wonder. Is there more to what’s happening than meets the eye?

Other questions pop into my head. The Baul sculpture was not advertised, as public art should be. No open competition, no shortlisting, no selection panel. On the contrary, the contract seems to have been awarded as a personal dispensation. The only condition seems to have been that the sculptor must get-hold-of-a-sponsor. High regard for public art, for Baul tradition, listed by the UNESCO as a world cultural heritage, and for procedural matters. Particularly by a government whose raison d’etre is establishing the rule of law, and rooting out corruption.

Simplifying the present: from `1971′ to the `Talibanisation’ of Bangladesh

British historian Eric Hobsbawm terms what he calls the ‘short twentieth century’, The Age of Extremes (1994). I can’t help but think, things seem to be getting more extreme in the twenty-first century.

In his most recent book, On Empire. America, War and Global Supremacy (2008), Hobsbawm traces the rise of American hegemony, the steadily increasing world disorder in the context of rapidly growing inequalities created by rampant free-market globalisation, the American government’s use of the threat of terrorism as an excuse for unilateral deployment of its global power, the launching of wars of aggression when it sees fit, and its absolute disregard of formerly accepted international conventions.

The US government’s role in not only contributing to the situation, but in constituting the conditions that have given rise to extremes, of being the extreme, is disregarded by many Bangladesh scholars, whether at home or abroad. Most of these writings are atrociously naive, exhibiting a theoretical incapacity to deal with questions of global inequalities in power. Authors repeatedly portray American power — in whichever manifestation, whether economic or cultural, military or ideological — as being benign. Two images of Bangladesh are juxtaposed against each other, a secular Bangladesh of the early 1970s, the fruit of Bangladesh’s liberation struggle of 1971, and a Talibanised Bangladesh of recent years. `National particularities’ and ‘the dynamics of domestic policies’ are emphasised (undoubtedly important), but inevitably at the cost of leaving the policies of US empire-building efforts un-examined.

One instance is Maneeza Hossain, Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute, who, in her 60 page study of the growth of Islamism in Bangladesh politics, tucks in a hurried mention of US’ supply of weaponry to Afghan jihadists, and moves on to call on the US to shake off its `indifference’ to Bangladesh, to use its ‘good offices’ to help democratic forces within Bangladesh prevail (The Broken Pendulum. Bangladesh’s Swing to Radicalism, 2007.

Ali Riaz, who teaches at Illinois State University, author of God Willing. The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh (2004) provides another instance. International reasons for the rise of militancy are the Afghan war, internationalisation of resistance to Soviet occupation, policies of so-called charitable organisations of the Middle East and Persian Gulf, and (last, it would also seem, the least) `American foreign policy’. A token mention showing utter disregard towards 1,273,378 Iraqi deaths, caused by the invasion and occupation. 1971 was genocidal, but so is the Iraq invasion. On a much larger scale. Unconcerned, he goes on, policy circles in the US are `apprehensive’ about militancy in Bangladesh. Even now. The solution? He advocates open debates, particularly between the intelligence agencies and the political parties (Prothom Alo, 3 February 2008).

And then one comes across Farooq Sobhan who claims that president Bush has ‘taken pains’ to convince Muslims that the war against terror is not a war against Islam or a clash of civilizations (no, it’s a crime against humanity). Rather petulantly, he asks, why has Bangladesh, a Muslim majority country, not figured prominently on the US ‘list of countries to be wooed and cultivated.’ Further, he writes, “High on the US agenda has been the issue of Bangladesh sending troops to Iraq“. Sending ‘troops’, like crates of banana, or tea? Surely, there are substantive issues — of death and destruction of Iraqis and Iraq, of war crimes — involved.

Re-configuring Politics during Emergency

Creating a level playing field so that free and fair national elections could be held, that’s what the military-backed caretaker government had promised. Twenty-two months later, after failed attempts at minusing Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina, with their respective parties in shambles, thousands of party workers in prison, constitutional rights suspended due to the state of emergency, economy in tatters, police crack-downs on protests of garments workers, jute mill workers, women’s organisations and activists, on human chains against increasing prices of essentials, the only two forces to have remained unscathed are the Jamaat-e-Islami, and Muslim clerics, Islamic parties and madrasa students, those who protested against the Women Development Policy, agitated for the removal of Baul sculptures, recently caused havoc in the DU Vice Chancellor’s office protesting against newly-enforced admission requirements. Are these accidental, or deliberate governmental moves? I cannot help but wonder.

Several western diplomats — members of the infamous Tuesday Club, particularly ambassadors from United States, Britain, Canada, Australia, and the EU representative — and also the UN Resident Coordinator actively intervened in Bangladesh politics prior to 11 January 2007, in events that led to the emergence of the present military-backed caretaker goverment. Renata Dessalien did so to unheard degrees, leading to recent demands that the UN Resident Coordinator be withdrawn.

In a week or so, the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon arrives in Dhaka, to see for himself electoral preparations, and extend support for the government. A visit that has nothing to do with politics, we are told. In the eyes of many observers, Ban is one of the most pro-American secretaries general in it’s 62-year history. He has opposed calls for a swift US withdrawal from Iraq, and is committed to a beefed-up UN presence in Baghdad. The UN staff committee has protested Ban’s decision saying it would `make the institution complicit in an intractable US-made crisis’ (Washington Post, 24 September 2007).

In the name of bringing ‘beauty’ to politics in Bangladesh, the lineaments of political reconfiguration undertaken by this military-backed caretaker government are becoming ominously clear: mainstream political parties in shambles, Jamaat-e-Islami intact (`democratic party,’ Richard Boucher, US Assistant Secretary of State, 2006), Muslim clerics and Islamic forces re-emerging as a political force under state patronage, and the exercise of rampant power by western diplomats.

A beast in the guise of beauty? Time will tell.

On the Flight Path of American Power

I borrow the title from British-Pakistani historian Tariq Ali’s coming event: `Pakistan/Afghanistan: on the Flight Path of American Power,’ to be held at Toronto, November 14.

Seven years after the US led invasion, Pakistan, America’s strong military ally, is now “on the edge” of ruin. Pakistani political analysts repeatedly warn Bangladeshis that they see similar political patterns at work here: minusing political leaders, militarisation, milbus, National Security Council etc etc. I do not think that an Obama win will make any difference to the American flight path for unilateral power. As atute political commentators point out, Obama and McCain differ on domestic policies, not substantively on US foreign policy. A couple of days ago, president Bush signed the highest defense budget since World War II.

Maybe there should be an open public debate in Bangladesh, as Ali Riaz proposes, but with a different agenda: are we being set on America’s flight path to greater power by this unconstitutional, unrepresentative government, one which is more accountable to western forces, than to us?