By Rahnuma Ahmed

“…my revenge would be just another part of the same inexorable rite.?I have to break that terrible chain.”

(Isabel Allende, The House of the Spirit, 1982).

But to break the “terrible chain” of vengeance, our leaders would have to recognise it as such. As terrible.

Our leaders would have to learn to see it not through the eyes of their political sycophants? ranging from lawyers to writers, journalists, academics, bureaucrats etc., etc.?but through the eyes of the public, who, by the way, are not fooled.

I watched news on a private TV channel the night of the hartal, called by the BNP the day after Khaleda Zia had been evicted from her Dhaka Cantonment house on 13 November. The news reporter asked different people, some waiting at Dhaka city bus stands, with children, bags and baggage ready to go home for Eid, others standing in long queues at ticket counters in Kamalapur rail station, several others searching in vain for motorised transport, may be to do last-minute Eid shopping. I watched all those interviewed, except one, unequivocally blame both parties for the hartal. They blamed both sides, not only the BNP, as the government seemed to have hoped.

The government should not have evicted her, they said. The BNP should not have responded by calling a nation-wide hartal, they added. A common refrain seemed to be, they couldn’t care less about us.

Top legal experts, those not belonging to the ruling party’s enchanted circle of lawyers, have said, the government should have waited for the Supreme Court ruling. Eminent jurist M Zahir has said, since the Supreme Court had fixed November 29 for hearing Khaleda Zia’s leave to appeal petition, the government should have waited for the court’s decision. It should not have acted hastily. While jurist Shahdeen Malik clarified the issue further, if there is no pressing need to implement the earlier judgment, it is customary to wait for the court’s verdict once an appeal has been filed. The purpose of the High Court verdict?that Khaleda Zia should vacate her house in 30 days?was not to lead to “chaos and instability” (Daily Star, November 14 2010).

The government does not seem to have cared about its international bhabmurti (image) either, a point that it invariably raises, like all other governments, to discredit political dissent. The BBC spoke of popular concerns that the eviction may revive “bitter rivalry” between the two women leaders known as “battling begums” (November 13). While The Economist headlined it’s piece, `Bangladesh. Politics of hate. An ancient vendetta continues to eat away at public life’ (18 November 2010). Despite a huge majority in parliament, the AL is `obsessed’ with the BNP, it is “stuck in a divisive politics based on personal grievances that go back nearly four decades.” It added, “Shrewdly Sheikh Hasina has allocated the vast plot surrounding Mrs Zia?s home for housing for the families of 57 military officers killed in a mutiny early last year, soon after the AL swept to power.”

Why should Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League always have to be broad-minded? Does not Sheikh Hasina too, have feelings and emotions like Khaleda Zia? Does only the BNP have a monopoly on wreaking vengeance? writes journalist Bibhuranjan Sarkar (`Khaleda Zia dekhaben shongkirnota ar Hasina dekhaben udarota!’)?while London-based columnist Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury seems more cautious as he warns the AL not to tread in the former BNP government’s path of deviancy. Restoring Bangabandhu’s image as the father of the nation and undoing distortions made to the nation’s independence history is needed, not drilling holes into Ziaur Rahman’s murals at Bangabandhu stadium in the middle of the night (`BNPr durbrittoponar onukoron dara deenbodoler protisruti shombhob noy’)

Newspaper reports indicate that the BNP leadership plans to launch a tougher anti-government movement after Eid, there is also talk of the possibility that BNP parliamentarians’ may tender their resignation en masse. The Awami League government seems to have finally succeeded in maneuvering its rival party into a tight corner, into launching a movement (merely) for recovering its leader’s house, a movement that renders all other issues, national issues, subsidiary. But the mirror image of this, of course, is that it has maneuvered itself into a tighter corner with its inability to deliver anything else to the nation. Control escalating food prices. Ensure gas and electricity supply. Decent wages for garment workers. Reign in the leaders and members of its student and youth organisations who seem to be exclusively pre-occupied with extortion, tender manipulation, sexual harassment, factional infighting and vandalising examination centres for recruitment to public posts. A deteriorating law and order situation which has given rise to acts of public vigilante-ism. Restoring the civil administration’s confidence after the Pabna debacle. Put an end to extra-judicial killings etc. etc.

Anything else but bitter rivalry. The politics of hate. Ancient vendetta. Divisive politics. Shrewdness.

Was evicting Khaleda Zia from her home a turning point in national politics, leaving the public in no doubt that times, unfortunately, have not changed? Does the future signal an inexorable downhill-all-the-way slide in the AL government’s popularity? As did the BNP-Jamaat government’s popularity after the August 20 2004 grenade attacks on the AL rally, aimed at eliminating the top AL leadership including Sheikh Hasina? Or, the revulsion felt by any decent person towards Khaleda Zia’s macabre delight in celebrating her fabricated birthday each August 15th, the day Sheikh Mujib was assassinated alongwith nearly all family members.

There seemed to be a perceptible change in public mood on hartal day. `Shala public ke bojha daey’ is a popular saying in Bangladesh dating back to the British colonial era, and shala public seemed not to be taken in by the government’s rhetoric about the urgency of eviction in order to uphold the rule of law. Shala public seemed to know fully that the eviction does not serve to better either the public’s present, or, its future. That it is part of the same inexorable rite of vengeance.

Khaleda Zia insists that she was forcibly evicted from her home, that her bedroom door was broken down, that she was forced to leave in the clothes she was wearing, that she was subjected to verbal abuse, that the law-enforcers dared to utter words to the effect that if she did not leave willingly, she would be carried out physically. An ISPR (Inter Service Public Relations) press release has alleged that her account was a blatant lie, that it was false and motivated. That she was abusive, calling the armed forces personnel “ungrateful dogs” and the “nation’s enemy.”

There are no independent accounts of what occurred on the day the eviction took place as journalists (alongwith her lawyers) were not allowed to enter the cantonment. However, members of the media were taken on a guided tour of her house the next day, when the premises should actually have been, or remained, sealed.

What concerns me is how Khaleda Zia’s persona has been constructed through the ISPR’s news release, statements made by a government minister, and other high-ranking AL leaders. The ISPR press release says, `she was not up by 9:30,’ `later at 11:00 a.m., she came to know that the authorities had come to ask her to vacate the house,’ `she started getting ready casually and spent two hours for makeup and other related activities’ implying that she is indolent, has no clue of what goes on inside her house, is frivolous and vain. Shamsul Hoque, state minister for home affairs, replying to questions raised by the media said, `if she was really dragged out of the house, why was her sari not ruffled up and her lipstick not messed up?’ implying that she was a blatant liar. What Khaleda Zia chooses to wear and how she dresses up is not the issue, or at least it is not my issue, what concerns me is that the “bitter rivalry” seems to extend to personal looks, and appearance. But why? Does it create psychological insecurities? And of course, one can hardly fail to notice the symbolic violence behind the state minister’s mention of ruffled up sari, messed up lipstick. Official discourses that accompany the eviction beg the question, was the illegality of the allotment at stake? At all?

During the guided tour of her house, an army officer reportedly requested a journalist to open a drawer of her bedside table in her bedroom, leading to the discovery of pornographic material. What does this indicate? That the ruling party’s `obsession’ with Khaleda Zia is a sexual obsession (since it extends to sexualising her), that army officers too, are presumably involved in this, and that all this can occur during the reign of a woman prime minister? Intelligence agencies are widely believed to have planted incriminating material during house searches, most recently, this occurred during the military-installed caretaker government’s rule (2007-2009). Is this what took place after Khaleda Zia was evicted? One of the complaints made against the former prime minister is that living in the cantonment has an adverse political effect on the army, that the national army should be kept apart from politics, so that civilian, political rule reigns supreme. Does it?

In The House of the Spirits Alba’s struggle was not against the military regime, but against her initial desire for vengeance after having been raped, tortured and imprisoned in a concentration camp. By beginning to question her hatred, she was able to rise above the inexorable rite of vengeance.

Our leaders too, need to break the terrible chain of vengeance. We have to compel them to do so. Through exposing both acts of state terror and thick walls of sycophancy. Through resisting leadership cults, whether governmental, or oppositional. Through forcing them to serve the public’s interests, not their personal enmities and hatreds.

Vengeance is best left to the gods, not mere mortals.

Published in New Age, 22 November 2010

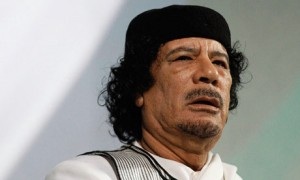

On the dusty reaches out of Sirte, a convoy flees a battlefield. A NATO aircraft fires and strikes the cars. The wounded struggle to escape. Armed trucks, with armed fighters, rush to the scene. They find the injured, and among them is the most significant prize: a bloodied Muammar Qaddafi stumbles, is captured, and then is thrown amongst the fighters. One can imagine their exhilaration. A cell-phone traces the events of the next few minutes. A badly injured Qaddafi is pushed around, thrown on a car, and then the video gets blurry. The next images are of a dead Qaddafi. He has a bullet hole on the side of his head.

On the dusty reaches out of Sirte, a convoy flees a battlefield. A NATO aircraft fires and strikes the cars. The wounded struggle to escape. Armed trucks, with armed fighters, rush to the scene. They find the injured, and among them is the most significant prize: a bloodied Muammar Qaddafi stumbles, is captured, and then is thrown amongst the fighters. One can imagine their exhilaration. A cell-phone traces the events of the next few minutes. A badly injured Qaddafi is pushed around, thrown on a car, and then the video gets blurry. The next images are of a dead Qaddafi. He has a bullet hole on the side of his head.