rahnuma ahmed

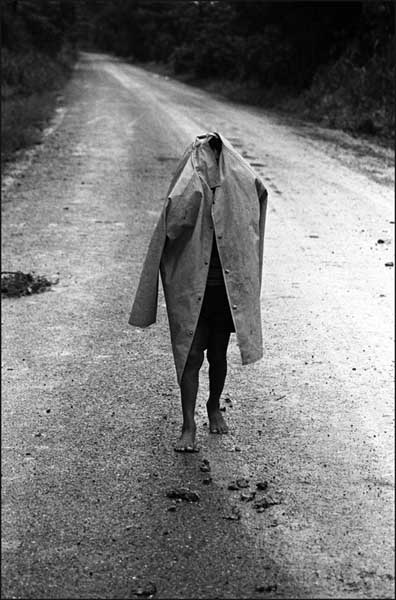

She jumped down from the police van and tried to escape. It stopped, they hunted her down by torchlight, dragged her back and drove off. Men, gathered around the tea stall, wondered why the car had stopped. Curious, they walked up to the spot. A golden coloured sandal, a handkerchief, and broken bits of bangle lay there.

Yasmin: raped and murdered by the police

She was only fourteen years old, her death was brutal. Gang-raped by policemen, and later, killed. Yasmin, a domestic wage worker, employed in a Dhaka city middle class home, longed to see her mother. Leaving her employers home unannounced, she caught the bus to Dinajpur, got down at Doshmile bus stoppage, hours before dawn on 24 August 1995. A police patrol van driving by insisted on picking her up. Yasmin hesitated. One of the police constables barked at those gathered around the tea stall, We are law-enforcers, we will drop her home safely. Don?t you have any faith in us?

Hours later, a young boy discovered her bloodied dead body, off the main road. The police who came to investigate stripped her naked. Bystanders were outraged. Recording it as an unidentified death, they handed over her body to Anjuman-e-Mafidul Islam for burial.

The dead girl was the same girl who had been picked up by the police van, when this news had spread, a handful of people took out a procession. In response, the police authorities held a press conference where a couple of prostitutes turned up and claimed that the dead girl Banu, was one of them, she had been missing. District-level administration and local influentials joined in the police?s attempts to cover up.

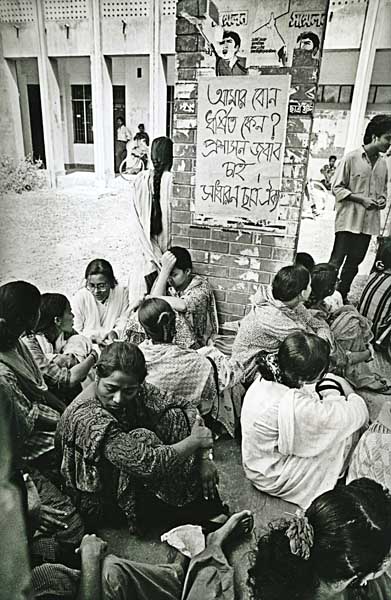

Spontaneous processions and rallies took place demanding that the police be tried. Yasmin?s mother recognised her daughter from a newspaper photo, lifeless as she lay strewn in an open three-wheeled van. As a peoples movement emerged, police action, yet again, was brutal. Lathi-charge, followed by firing, killed seven people. Public outrage swelled. Roadblocks were set up, curfew was defied, police stations were beseiged, arrested processionists were freed from police lock-ups by members of the public. Outrage focused on police superintendent Abdul Mottaleb, district commissioner Jabbar Farook, and member of parliament Khurshid Jahan (?chocolate apa?), the-then prime minister Khaleda Zia?s sister, perceived to be central figures in the cover-up. Shommilito Nari Shomaj, a large alliance of women?s organisations, political, cultural and human rights activists joined the people of Dinajpur, as Justice for Yasmin turned into a nationwide movement.

In 1997, the three policemen, Moinul Hoque, Abdus Sattar and Amrita Lal were found guilty. In 2004, they were executed.

Yasmin of Dinajpur is, for us, an icon symbolising female vulnerability, and resistance, both her own (she had tried to escape), and that of people, both Dinajpur and nationwide. She serves as a constant reminder that the police force, idealised in state imaginings as protector of life and property should not be taken for granted, that women need to test this each day, on every single occasion.

In the nation?s recent history of popular struggles, Yasmin?s death helped to characterise the police force as a masculine institution, it gave new meanings to the Bangla proverb, `jey rokkhok shei bhokkhok,? he who claims to protect women, is the usurper, the aggressor. A taboo, sanctioned by state powers, was broken.

Bidisha in remand: sexual abuse

`Go and get a shard of ice. Insert it. It will all come out.?

In her autobiography, Bidisha, second wife of ex-President Hussain Mohd Ershad, later-divorced, writes, I wondered, what will they do with that? Insert it where? (Shotrur Shonge Shohobash, 2008).

Under the influence of what she assumes was a truth serum, injected during remand at a Joint interrogation cell housed in Baridhara, Bidisha writes, the pain was unbearable. A horrible burning sensation coursed through my body, my eyes threatened to burst out of their sockets. If I opened them, it felt like chilli powder had been rubbed in. If I closed them, balls of fire encircled my pupils. My breathing grew heavy. I felt like I was dying, but I couldn?t, I was falling asleep, but I couldn?t. My tongue grew thick. I wanted to say everything that I knew, and things that I didn?t. Questions flew at me from all directions, some of them pounded me from inside my head.

But, Bidisha writes, I stuck to what she knew. I stuck to the truth. Her interrogators got tired. One of them ordered the ice, and ordered someone to leave the room. Was it the policewomen, Bidisha wonders. A strong pair of hands gripped her shoulders, another climbed up her legs, up her thighs, ?like a snake.? But they stopped, disappointed. `I don?t think we can do it. She?s bleeding.?

She writes, but my periods had ended days earlier, why should there be blood? I remembered, it must be the beatings at the Gulshan police station, by the officer-in-charge Noore Alam. She was pushed and as she fell, someone grabbed hold of her orna. Pulled and pushed, her orna soon turned into a noose, she could no longer breathe, her tongue jutted out. She was hit hard with a stick on her lower abdomen, through the daze she could see that he was uniformed. I fell on the floor like a sack. I was barely conscious. I was kicked and trampled with boots on my chest, head, back, and lower abdomen.

During interrogation, the chief interrogator Joshim had repeatedly shouted at her, Do you know who I am? Do you know what I can do to you? Ten-twelve men had been present when the truth serum was injected. Well-dressed, fashionable clothes, expensive watches. Whiffs of expensive after-shave. Trim hair, cut very short. As she repeatedly stuck to the truth, Joshim threatened to hang her upside down, like Arman, he said, who was being tortured in the next room. She was threatened with rape by members of RAB (Rapid Action Battalion). During another round her left thumbnail was prised open and torn away, by something like a pair of pliers. They held my eyelids open so that I could see. Relief came only when the call for prayers sounded, since the men scurried away to pray.

Interrogation sessions were video-recorded, each interrogator had an audio recorder. I remember hearing, be sure to get all the details on camera. I remember someone adding, Who?ll think she?s had three kids? What a figure! The cassette?ll make him happy. Make who happy? she wonders. Toward the end of the three-day remand, one of the men entered and said, It?s over. I?ve talked. To who? asked one of the interrogators. One of the Bhaban men. (I presume, Bidisha means Hawa Bhaban). She was forced to declare on camera that she had not been tortured, to sign written declarations, and also blank sheets of paper.

She was in custody for 23 days in June 2005, because of two cases filed by her husband, and two by the government. What were the allegations? Her husband, the ex-President, first accused her of stealing his cell phone, money from his wallet, and vandalising household furniture. Then she was accused of having different birth dates on two different passports. And lastly, of having stashed away large amounts of money in foreign bank accounts.

Interested quarters tried to make light of the incident, they said, it was a ?purely family affair.? Those in the political know, for instance Kazi Zafarullah, Awami League presidium member, claimed that the ruling BNP had masterminded the event to prevent Ershad from forging unity with opposition political parties since elections were due next year (New Age, 6 June 2005). I was repeatedly asked during interrogation, writes Bidisha, why had I said that the Jatiya Party should form an alliance with the Awami League? Why not with the BNP? (`because they were unable to govern properly, people were furious, Jatiya Party popularity was bound to fall?). Bidisha was expelled from Jatiya party membership, she lost her post of presidium member.

Parliamentary elections under the present military-backed caretaker government are scheduled to be held in December 2008. Jatiya Party (JP) has joined Awami League (AL) led grand alliance for contesting the elections. According to newspaper reports, Ershad is eyeing the presidency.

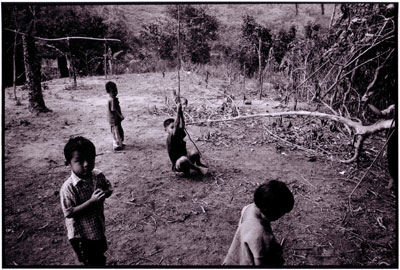

Pahari women: rape under occupation

Even after the signing of the 1997 Peace Treaty between the government and the PCJSS (Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti), the Chittagong Hill Tracts remains one of the most militarised regions of the world. During the period of armed conflict, according to international human rights reports, sexual violence was inflicted on indigenous women and their communities as part of military strategy. Bangladesh Army personnel have been accused by paharis of having committed extrajudicial killings, rape, torture and abduction. In August 2003, over 300 houses in 7 pahari villages of Mahalcchari were razed to the ground by the army, aided by Bengali settlers. Paharis claim, ten Chakma women were raped, some of them gang-raped. This includes a mother and her two daughters, aged 12 and 15, and two daughters of another family, aged 14 and 16 years. Victims allege, armed personnel alongwith Bengali settlers took part in the rapes. Paharis claim, state-sponsored political and sexual violence still continues.

There is no public evidence that the Bangladesh army has investigated those claims in any way. Nor do we know if the Bangladesh army has charged any soldier as a result of the alleged assaults. Nor is there any public evidence that any military personnel has been punished for any of the alleged rapes.

Tomorrow, November 25 is the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. We need to break more state sanctioned taboos.