![]()

With hundreds of people seeing the show every day, and excellent media

coverage, it might appear as if the staging of WPP photo in Bangladesh was a

smooth well organised affair. As Marc will testify, the reality was very

different. For those of you who have seen the show at the gallery or online,

this behind the scenes look will provide an amusing take on a potential

disaster.

The crates had arrived at Zia International Airport on the 24th of December

2003, but the journey from Zia to Dhanmondi took considerably longer. The

opening was at 4:00 pm on the 7th January 2004. By 3:30 pm, the crates

hadn’t arrived! We did know they had left the airport, and was able to tell

the Dutch Ambassador that it was safe for him to come over. The head of the

caretaker government, our chief guest, Justice Habibur Rahman was already on

his way. The adrenaline was flowing!

Tag: Bangladesh

Victory's Aftertaste

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Rashid Talukder’s photo of the dismembered head in Rayerbazar

(http://www.drik.net/calendar96/), or the Pullitzer winning image by Michel Laurent and Horst Faas, of the bayoneting of Razakars have been used to represent Bangladesh’s war of liberation. Kishor Parekh photographed a different war. An old man held up a tiny flag of the new Bangladesh. A child cast a furtive glance at a corpse in the street. Jubilant children laughed as they ran across mustard fields in bloom. Women shed silent tears. “Shoot me right now, or take me”, he had said to the major who refused to take this unaccredited photographer. But Parekh did board the helicopter, but then went his own way. On his own, with limited film, Parekh photographed the war that ordinary women, men and children had fought.

Shahidul Alam

Sat Dec 20, 2003

Fraud Band

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

She was mildly self conscious when I asked to photograph her, but a smile soon spread over her face. The telephone had connected her to her husband, a worker in Singapore. Salma, a woman in a village near Sonargaon in Bangladesh, had recently learnt to use the village mobile telephone, and it had transformed her life. Had this been where the story ended, it would have been a simple affair with a happy ending. Perhaps for Salma, it wasn’t significant that the technology that allowed her access to her husband, was one of many that allowed people in distant lands to tap her call, to add her to a database, to classify her as yet another consumer of products or a source of cheap labour for electronic sweatshops. For many others however, the wealth of new opportunities provided by globalisation, merely represents a wider net for global exploitation.

There are now many Salmas, and on the 14th August 2003, Grameen’s subscriber base reached a million. Greater than the total subscriber base of the government land lines. ISPs too pop up in many street corners, and though Internet telephony (VOIP) is illegal here, the service is openly advertised in convenience stores. In between the tangled wires on every street pole in Dhaka is the attractive advert: broadband, 24 hours, only taka 1000 per month. That’s about US $ 17. Not a bad price for broadband, until you realise that the definitions differ. The bandwidth on offer is 1K/sec, and breaks every time a storm, or a competing ISP cuts the cable, or when electricity fails (generally 2-3 times a day) at any of the relay nodes. No wonder many users call it ‘fraud band’.

The VSAT on our rooftop delivers 512K connectivity. A respectable speed, except that we expect to have 200 dialup customers, another 200 leased line clients, and maybe a few smaller ISPs running Voice over IP (VOIP) services and the ‘broadband connections’ using that bandwidth. That is the only way we can pay for the US $ 3500/month for staying connected. Plus a $ 3,500/64 KB/year license fee. An average user in the west would pay around 20 – 30 Euro for comparable access.

Even getting here hasn’t been easy. In 1994, when we setup Bangladesh’s first email service, we were using off-line email. Our server, a 286, and just one telephone line which we used for voice, fax and email, provided email connectivity to the world bank, UNICEF, major universities, and several organisations that are now ISPs. Since then the Net has been both a boon and a bane. It has been our lifeline to the rest of the world, and it has been the area where the government has attacked us the hardest. On the 27th of February 2001, we setup the country’s first human rights portal www.banglarights.net. The government promptly closed down all our telephone lines the next day. It took a lot of protests, to get the local lines back, but even now, we cannot make an international telephone call. Not using the government lines anyway. However, our VSAT on the rooftop, allows us an access that the government will not be able to stop simply by pulling a plug somewhere. Our e-newsletter reaches a carefully targeted 5000 worldwide, and a note saying the government was getting heavy would be immediately followed by a string of protests from fairly

influential organisations worldwide. So we walk a fine line, and continue to be subversive. On the other hand, the government’s lack of knowledge can be used (and abused) to find ways round the system. The import of the satellite phone by the BBC, which connects through Inmarsat, was allowed by the Bangladesh Telephone and Regulatory Council (BTRC), on condition that it not be used to make calls outside the country!

For the majority world, education offers the most effective route to take advantage of the globalisation juggernaut. And it is here, that the technological opportunities and the networking that accompanies globalisation, can be best utilized. Interestingly, the role models that seem to have worked best are those developed in the south, and it is only when the asymmetrical flow of information, which flows essentially from north to south, is replaced by south-south movement, that we will begin to turn the tide around. We started using the Net for education fairly early on, but activism and survival have really been the main driving forces behind our relationship with new media. An incidence of rape at a local university was being hushed up, and it was our presence on the Net that forced the establishment to arrange an investigation. The rapists got off with mild punishment, but it was the first time they had been challenged, and it has changed campus dynamics. It was our fragile network that allowed us to contact legal help groups and other activist organizations, when Taslima Nasreen, the feminist writer was under threat. It was the Net that kept us relevant.

The most interesting shifts have been in the area of media. With mainstream media coming under increasing restrictions, and the cost of publishing soaring, media activists have been taking to the Net to get their ideas across. A whole set of blogs, newsletters, opinion forums and activist sites have sprung up. Apart from providing an alternative space where points of view not palatable to mainstream media can be aired, these Net spaces have also become meeting grounds for the diaspora, who have until now felt excluded from the development process, and numerous archives abound providing alternative information sources.

The main struggle however remains between activists trying to make full use of a vibrant media, and a skeptical, fossilized and generally corrupt bureaucracy, that is deeply suspicious of what this media might do. It is reminiscent of the first time Bangladesh rejected the fibre optic cable that went along the Bay of Bengal, since the information minister was scared that ‘state secrets’ would be leaked out. A new rule in Bangladesh prevents CDs from being sent overseas, while the same data sent through the Net can be sent legally.

Our journalism school is trying to develop on-line learning modules, and we are hoping to start up a regional centre for investigative journalism that will rely heavily on new media for its success. There are interesting political implications too. Our latest plans for setting up a ‘public accountability site’, promises to be the most problematic for the establishment. The idea is to setup kiosks in poor neighbourhoods, which will provide information relevant to the locality that they can use to determine how public funds and other resources are being used. The government has promised such transparency, and we want to hold them to it. But when the public begins to sense how their resources are used, the trouble will start, and those who made the ministerial speeches, will be the first to shut us down. That too is a fight that we need to win, and we’ll use new media as our primary tool.

Presented at the World Summit on Information Society. Geneva. 9th December 2003

Remaking Destiny

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

www.migrantsoul.org

Who am I? Where do I belong? Who determines my future? Society has no answer to these restless questions. Our sense of identity, kinship and community, are at worst shattered by the experience of migration and at best are thrown into uncertainty.

The universal declaration of human rights talks of a world “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”. The reality, particularly for the economic migrant, is very different.

Physical, emotional, social and intellectual exclusion reinforce a migrant’s sense of displacement and alienation. The powerful may glide over such barriers, touching down for business, for pleasure or even out of guilt. For those without power, parting is painful, and each barrier crossed, like the ferry ghats of the big rivers, broadens the distance they must travel to return.

Expectations, dreams, duties and needs circumscribe the life of an economic migrant. The single hope, to change one’s destiny, is what ties all migrants together, whether they be the Bangladeshis who work in the forests of Malaysia, the bonded labourers in the sugarcane plantations in India, the construction workers in the Middle East or the hopeful thousands bound for the promised lands of Europe and North America. They see migration not merely as a means to economic freedom, but also as a passport for social mobility. The wealthy can purchase the future they desire. But a migrant who chooses to rewrite an inherited destiny swims against the current and faces the wrath of the gatekeepers who shape that destiny.

Shahidul Alam

Fri Jul 18, 2003

From Seventh Fleet to Seventh Cavalry

25th March 1971. My eldest niece had just been born the day before. It was a premature birth. Amma had found a Mariam flower and the flower had bloomed, heralding the birth. She had stayed behind at the clinic. We had felt something was afoot, and Babu Bhai and I went out to try and get mother and child back from Dr. Firoza Begum’s clinic in Dhanmondi. Our home might not have been safer, but at least we’d be together. Friends were building roadblocks in the streets by then, and let us through reluctantly, warning us that we had little time.

We went along the narrow road by Ramna Police station to Wireless Mor, it being too dangerous to go along the main road. I climbed over the barbed wires on the boundary walls to get to my sister’s flat, but my brother in law felt it was too dangerous to go out, so I turned back. By then the tanks were on the streets.

I had fallen asleep, but woke up to the sound of gunfire. The wide red arcs of tracer bullets had lit up the sky. The only tall building nearby was the Hotel Intercontinental, where the meetings between Mujib and Bhutto had taken place, and where the foreign journalists were staying. The slum next to the Sakura Hotel and the nearby\ newspaper office were ablaze. We could hear the screams. Those who were able to escape the fire, ran into the machine gun fire waiting outside.

Abba (my father), Babu Bhai and I watched in silence. We had argued with Abba about Pakistan, but he had been victimised as a Muslim in pre-partition India, and would not support what he saw as the break up of the nation. That night he finally broke our silence by saying, “now there is no going back.”

We heard the gunshots all night, and there was a curfew the following day. Eventually when there was a small break in the curfew the day after, Abba went to get supplies, and Babu Bhai and I got my sister and her daughter to Nasheman, in Eskaton where we lived. We called her Mukti, meaning `freedom’. But relatives warned us that it was too dangerous to use that name, even if it was a nick name to be used only amongst ourselves. So Mukti became Mowli, and even after independence, the name stuck.

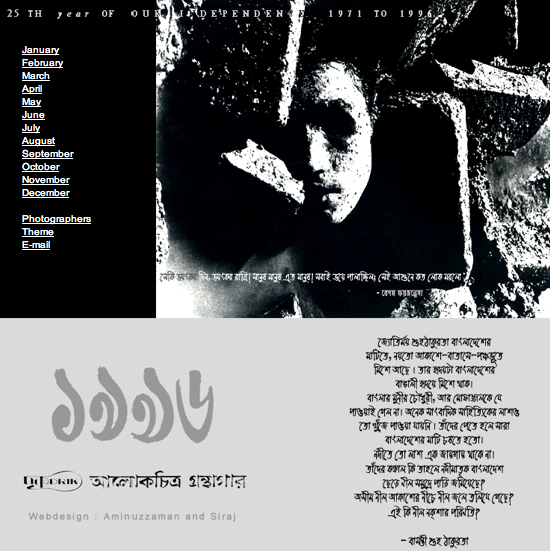

Twenty five years later in 1996, I tried to put together a collection of images of ’71 for our 1996 calendar. I am reminded of the introduction:

[Twenty five year ago, even longer perhaps, just a camera in hand, they had gone out to bring back a fragment of living history. Today, those photographs join them in protest. Peering through the crisp pages of the newly printed history books, they remind us, “No, that wasn’t the way it was. I know. I bear witness.”

The black and white 120 negatives, carefully wrapped in flimsy polythene, stashed away in a damp gamcha, have almost faded. The emulsion eaten away by fungus, scratched a hundred times in their tortuous journey, yellowed with age, bear little resemblance to the shiny negatives in the modern archives of big name agencies. They too are war weary, bloodied in battle.

So many have sweet talked these negatives away. The government, the intellectuals, the publishers, so many. Some never came back. No one offered a sheet of black and white paper in return. Few gave credits. The ones who risked their lives to preserve the memories of our language movement, have never been remembered in the awards given on the 21st February, language day.

25 years ago, they fought for freedom. They didn’t all carry guns, some made bread, some gave shelter, some took photographs. This is just to remind us, that this Bangladesh belongs to them all.]

Drik Calendar 1996

Today, embedded photojournalists with digital cameras, give us images of yet another aggression. This time, from the other side of the gun. The 50 clause contract that gives them access to imperial military units, like the unwritten rules that allow them access to presidential pools, ensure that `free’ media remains loyal to the warmongers. Will we ever get to see the images taken by the Iraqi photographers? Will their negatives die the same death? Will those images, like the bombed ruins of a magnificent city, be the only tattered remains of an aggression that the world allowed to happen? In ’71, the Seventh Fleet was stationed in the Bay of Bengal. The Mukti’s were not deterred by this show of power. They won us our independence. Today, after 43 more US military interventions across the globe, it is the Seventh Cavalry that bombs Iraq. And our own government, forgetting the lessons of history, forgetting that they tried to kill our unborn nation, turns against the will of its people. Our own police turn against us in our anti war rallies, to protect the biggest aggressor in history. These negatives may not survive, but the collective memory of the people of the world will, and our children will confront us in years to come.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

26th March 2003

* A flower from Arab deserts, used during labour to predict the time of childbirth.

** A working man’s cloth of coarse cotton, used as padding when carrying weight, to carry food, and to wipe away sweat.

The War We Forgot

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Iqbal had asked me when we first met. “Bhaiya, where are Barkat and Salaam’s graves?” I didn’t know. He was 10, I was 39. As a 15 year old in 1971, I had felt the warm flush of victory as I held a Pakistani Light Machine Gun in my hand. I hadn’t really won it in battle, but only recovered it from a burning military truck. But the joy was just as much. That was the time when a rickshaw wallah had refused to take my fare, because he had heard me greet a friend with ‘Joy Bangla’ (freedom for Bengal, the 1971 slogan symbolizing freedom from Pakistani rule). Things had changed, and the promise of our own land had slowly been eroded by politicians and military rulers who had lived off our dreams. Each time we became skeptical, each time we sniffed that something other than ‘Shonar Bangla (Golden Bengal)’ was in their minds, they led us on with vitriolic rhetoric. Eventually, as on that day in 1994, I too had forgotten. I didn’t know where Salaam and Barkat’s graves were. I had never heard of Dhirendranath Datta. More importantly, I didn’t care. But Iqbal did. Born long after Salaam and Barkat’s bodies had merged with the soil, Iqbal only knew of this great battle that we had fought. Though the heroes had changed depending upon who ruled the country at any particular time. Salaam and Barkat were beyond dispute. They were not a threat to anyone. They didn’t apply for a trade license, or bid for a government tender. It was safe for the history books to remember them. Remembering Hindus or women was a bit more problematic.

My search for these other heroes, the ones with cameras, began in 1994. After Iqbal reminded me that I had forgotten. It was in the Paris office of Sipa that Goksin Sipahioglou, excited at my presence ran down the stairs and brought back with him an armload of slide folders. It took a while for it to sink in. These were the first colour photographs of the Muktijudhdho that I had ever seen. We had heard that some of these photographs had been published. But our only source of news at that time was Shadhin Bangla Radio. It talked of the glory of our freedom fighters, of how they were fearless against enormous odds. Of their glory in battle. M R Akhtar Mukul in ‘Chorompotro’ was the one voice we longed for. We chuckled as he talked of the plight of the Pakistanis. His wry but animated voice, muffled by the blanket we hid under, and barely audible in the turned down volume of the transistor radio, gave us hope, and kept us going through the dark nine months.

It was Abbas’ photographs that Goksin had brought for me. Later that month, in the back garden of a house in Arle, I met Don McCullin. Don was excited about the show I wanted to do, and unhesitatingly agreed to give us pictures. I found Abbas, at a beach near Manila, quite by accident. Both of us had been following the golden late afternoon light in a summer evening in Manila beach. Abbas too was excited. He wanted to be part of the show. Michele Stephenson and I had been in the same jury of World Press Photo on two occasions, and I had plenty of time to tell her about my plans. She invited me to New York and arranged for me to go through the archives of her magazine, Time. It was in the basement of the Time Life Building in the Avenue of the Americas, that I came across the daily bulletins that the reporters had sent in.

Memories flooded through my mind as I remembered those harrowing days and nights. I remembered the screams of people being burned alive as the flame throwers belched fire at the Holiday office near the Hotel Intercontinental.

Most of the people who died were the people who slept in the streets and the slum dwellers around the newspaper office. Those who chose to escape the fire ran into a hail of machinegun bullets. My father, mother, Babu bhai and I, watched quietly from our verandah in Nasheman on New Elephant Road. My dad had suffered from Hindu bhodrolok prejudice in the pre-partition days, and had never supported the break-up of Pakistan. And we would have great fights in the home, the younger ones wanting independence, Dad’s generation feeling things could be patched up. That was the night Dad said it was over. No longer could we ever be one Pakistan.

I excitedly went through the reams of paper. Each scrap of news had a meaning for me. I could relate to these news bulletins. I remembered the horror of those nights. As I thumbed through a tattered red diary, I noticed the skimpy notes of a photojournalist as he traveled through Jessore. I remembered Alan Ginsberg’s poem. It was David Burnett’s diary. Several years later as David and I met in Amsterdam in yet another World Press Jury, I told him where his diary was. In Kuala Lumpur, Dubai, Delhi, and so many other cities have I picked up the scraps of evidence that would help me piece this jigsaw together.

It was in Paris that I spoke excitedly of my plans to Robert Pledge, the president of Contact Press Images. Robert shared my enthusiasm for the project, but I harried him with my feverish frenzy. We couldn’t wait, we had to do it now. That now has taken over six years. But in these years we have made the most amazing discoveries. The stories, the images, the people we have come across, make up the life of this exhibition. It is the war veterans, the men and the women in the villages of Bangladesh, who fought the war, the forgotten heroes with their untold stories, the men and women who were killed and maimed, the women who were raped that this show is dedicated to. It is not a nostalgic trip for us to romanticize upon. It is for Iqbal and his friends to know that Barkat and Salaam, were more than simply names in history books.

Shahidul Alam

November 2000. Dhaka

Chalking up Victories

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

At 17 Mozammat Razia Begum is older than most of the girls in her class at the Narandi School. She was married at 15 but her husband abandoned her.

?If I had been educated he would not have been able to abandon me so readily, leaving me nothing for maintenance,? she says. The marriage of young girls without proper contracts – followed soon after by abandonment – is a serious social problem in Bangladesh. Razia blames her parents. ?My parents were wrong to marry me off so young. If I had a daughter, I should not let her marry until she was at least 19.?

The school Razia attends is one of 6,000 non-formal village schools set up by BRAC – the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee – exclusively for pupils who have never started school and those who had to drop out. Three-quarters of the 180,000 pupils are girls. Although married girls are not normally catered for, exceptions are made. Many of the teachers are women: parents in Bangladesh frequently keep their daughters away from school if teachers are male. And each BRAC school is situated right in the community: if schools are far away parents will not let girls attend. It is not acceptable for girls – especially those past puberty – to walk about the countryside in this devout Muslim country.

?I am fortunate to be here,? says Razia, looking round the schoolroom with its tin roof and walls of bamboo and mud. She had to fight to come, though. Her father believes that a woman?s place is at home. ?Had I been a boy,? she said, ?my father would surely have allowed me to study.?

Razia?s own mother was married at 12 and, like her oldest daughter, had no say in the matter. ?I want my sisters? lives to be different. They should study and be given a choice about their marriage. Husbands will not dare to treat an educated woman badly.? On this subject, Razia becomes quite animated.

Razia would like to go on with her studies after she has completed the BRAC course. During the two-and-a-half hour daily session – which is timetabled to fit in with seasonal work and religious obligations – she learns literacy and numeracy, as well as enjoying activities such as singing, dancing, games and storybook reading.

BRAC have had a remarkable success in keeping the drop-out rate from their schools to five per cent and graduating 90 per cent of their students into the formal primary system. This proves that the obstacles to girls? education – even in such a poor environment – can be overcome.

As for Razia, her experience of life has forced her to question many things she once took for granted – such as the need to get married. She does not wish to marry again. And many other girls have begun to question the restrictions imposed on them. More of them want to be teachers – like their own teacher – or doctors. Razia says: ?I tell my sisters to study well and get a job. If they get a job they will be able to do as well as men and men will respect them.?

First published in the New Internationalist Magazine in Issue 240