We!

The children are reduced to bones

And skin. Their tiny bodies

Have heads appearing far too large

And eyes that cry for help.

But there’s no shortage yet of guns

And bullets — or of bombs.

And soon enough, you hear them come —

The jets that scream through skies

And drop the rain that’s so obscene

That voices then fall still.

******

The drones that fly like sightless birds,

The tanks that roll through streets,

The men who fire on passers by,

Who buys and pays these?

We!

****** Continue reading “We”

Tag: Children

Children's Art and Children's Rights

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Published on Saturday, September 24, 2011 by CommonDreams.org

by Claudia Lefko

We?ve been here before, confronting this question of children?s art, and why it creates such a stir. I wrote about it in May 2006 when Brandeis University cancelled an exhibit of Palestinian children?s art. This cancellation seems even more egregious because the museum in question is specifically a children?s museum.

Who objects to children?s art in a children?s art museum? And, what should we make of a children?s museum that allows the concerns of those constituents to censor the views of children, denying their right to expression? I?m talking about the Oakland Children?s Museum (MOCHA) and its decision to cancel the exhibit A Child?s View of Gaza, which was to have opened there this week, on September 24.

One can only conclude that those who have objected to this exhibit are troubled by the content. For whatever reason they want it buried, out of site and out of mind. They must be a powerful group. They succeeded in convincing the museum?s board to ignore its stated goal of ?…advocating for the arts as an essential part of a strong, vital and diverse community?. And, they have put the museum in the uncomfortable position of denying Palestinian children their rights as guaranteed by Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC): the right of every child to express his or her views and to have those views given due consideration.

?The artist’s job is to be a witness to his time in history.? said the artist Robert Rauschenberg, and so it is with our young artists. Seeing, as we know, comes before words. A child looks and recognizes people, places and things before she or he can speak; ?views? are developing from the moment of birth. So, imagine the views taken in during the long, wide-eyed hours of childhood in Palestine or in Baghdad on in Afghanistan. Imagine the tension, worry and preoccupation on the faces of the adults; imagine the looks on the faces of the of soldiers as they patrol the streets, or search homes. Imagine the hundreds upon hundreds of violent scenes that could and do play out in front of children living in war zones. This is their world. It surrounds them day in and day out. And oftentimes, they have not only no words, but no opportunity to tell us what they think and feel about this.

Taking crayon or pencil in hand, a child speaks out on his or her own behalf: this is me, my situation, this is what my life looks like. It isn?t easy for adults to bare witness to these stories. I?ve seen exhibits of children?s art from Hiroshima, from Spain during the Civil War, from Viet Nam, from Darfur, from the concentration camps in WWII and from Iraqi children. What we see in some of this art is the human cost of war, the terror and agony of being a child in an unpredictable, dangerous and violent world, a world gone inexplicably mad. A world where you are not safe, where even your parents cannot protect you.

This art is not about politics, it is about the human condition. If we cannot look at it, if it is too painful, it is because the world we have created, full of violence and conflict, is not one that is good for children. The famous 60?s poster with one giant flower said it all: War is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Things.

We have a legal as well as a moral obligation to let Palestinian children, and all children express their views freely and to give those views our due consideration. If we are disturbed by children?s images from war zones, we should work on their behalf to create a better, more just and peaceful world , a world where children are truly valued and where their care, protection and overall well being is a social, economic and political priority. To do anything less is to deny the significance of children as the future of our planet.

Aldous Huxley wrote this, in his introduction to ?They Still Draw Pictures! A collection of 60 drawings made by Spanish children during the war? (1938): The most that individual men and women of good will can do is to work on behalf of some general solution of the problem of large-scale violence and, meanwhile to succour those who, like the child artists of this exhibition, have been made the victims of the worlds collective crime and madness.

The museum, in canceling the exhibit has dealt yet another blow to children and their rights; surely a children?s museum, of all institutions, can do better than this.

To see examples from this exhibit: mocha.org

Claudia Lefko is the founding director (2001) of The Iraqi Children’s Art Exchange in Northampton MA. She is a long-time educator, activist and advocate for children.

From the other side of the fence

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

There is a certain arrogance in ?teaching? anything. The assumption that you know best, and the certainty that you are in authority. The clear hierarchy. Bhaiya and Apa, against tumi or tui. When advantages of age and access are coupled with differences of class, it forms a dangerous mix. One needs to tread warily. The medium of photography, because of its power, is a dangerous tool. One hopes to share the adventure of a new way of seeing, but stay alert to the traps of privileged voyeurism. To empower and not be patronizing. To open windows of opportunity. To let in fresh ideas, but not trample on thoughts that exist.

It?s been tried before. The novelty of teaching children, the moral high ground through providing what was absent, the exoticism of entering a world through eyes that have special access are ways in which new worlds have been ?discovered?. Rarely has it raised the question of the invisibility of worlds that leads to such discovery. Empowerment can only be explored where equality has previously been denied. How then does one approach exploitation? How does one undo wrongs when one is on the ?wrong? side of the fence?

There are no easy answers. No secret ingredient, that makes one immune to the hazards of benevolent intervention. Therein lies the magic of this medium. Stripped of the need for technical prowess that makes privileged knowledge a domain of the privileged. Unburdened by the material limitations of films and their cost. Liberated from the aesthetic leanings of conventional education, some children have a freedom that their ?well brought up? counterparts have long lost.

It?s a contagious spontaneity. A boy and his shadow, hovering in suspended animation, take the ?decisive moment? to new heights. Clutching her prized possessions, a little girl walks through a rubbish tip, her hesitant smile lighting up the drabness of her surrounds. A lonesome worker, drooped in toil, rests his weary body. These are not images made because of some learned aesthetics, or some schooling of shape or form. No complex law of composition can compete with the contours shaped by a caring eye. No sermon on tempo and pace can replace the irrepressible energy of unabashed youthfulness. No theory on the use of negative space can contain the sheer audacity of an unbounded horizon. Did the ?teachers? not have a role? Of course they did. They stepped out of the way when they knew the time was right. They coaxed and cajoled when a little prod was needed. They said ?yes, yes, yes?, when they saw hesitation in expectant eyes. They waxed the wings of flight. They let imagination soar.

These gentle, harsh, chaotic and elegant images remind us, not of some untapped potential that our intervention has released, but the humanity in abundance that our unabated surge for growth, leaves behind.

Exhibition and launch

Dhaka Diary

UNICEF website

His Life

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

By Gita L. Vygodskaya

Translated from the Russian language by Ilya Gindis

Published in School Psychology International, Vol.16

Nobody in our family studied or took up religion. I only knew from the nanny, who took care of us, that there was a God, whom she, according to her words, feared and respected. On several occasions, unknown to my parents, she even took me to a church. When my father found out, he, to much to nanny’s surprise, did not get angry. Upon finding from me that I liked church, and from the nanny that I did not disturb anyone there, he decided that in the future we could go to church whenever we wanted. I remember well how proud I was when we walked openly to church, wearing our best bonnets.

Later the nanny told me that every girl should know a prayer, and I learned one from her by ear, without understanding a single word. To all my questions she always answered: “I am illiterate, when you get educated you will understand everything”. But I did not want to wait until I grew up and was educated, and so I went to my father to clear things up. He seemed to be surprised when I recited the prayer from memory, and asked where I learned it. He did not express any feelings towards the whole matter, but simply explained that the prayer thanked the Virgin Mary for giving birth to the Lord Jesus Christ. This however did not yet mean anything to me, and I went about my business as before. One day Leonid, my older cousin, who lived with us, did something that was strictly forbidden. The nanny then warned him to never do it again or “God will punish you”. To this the boy quickly replied: “God does not exist”. The nanny was horrified, and began to tell him how you can’t say things like that. Leonid was unimpressed and stubbornly stuck by his comment.

Meanwhile I was completely confused by the whole matter and had no idea where the truth lay. I began to get upset and to get a straight answer I went to my father, as I always did in difficult situations. I remember well how he was sitting at the table working. I could not hold back the worrying question, and so I came up close, so he would notice me, a favorite tactic of mine. He put down the pen, turned and hugged me by the shoulders, asking what happened. “Dad, is there a God?” – I burst out. “Why do you ask me?” – he replied. I told him of the “discussion” between the nanny and Leonid. He suddenly become very serious. “You see,” – he said, “some people, like our nanny, believe that God exists while others reject the idea. Everyone must decide this for themselves, when you grow up you too will decide”.

He never forced his opinions on us, unless of course we were doing something really wrong. In most cases he preferred for us to work things out on our own. Often when we asked a question, he did not give a complete answer but rather drew us into discussions that resulted in a commonly agreed on answer or decision.

A few years before his death, my father began to smoke. No one was really bothered by this as he did not smoke often, and it seemed to make him happy. I liked to watch him as he smoked, he had a special sort of smile at these times. One day Leonid told me how unfair he thought it was that we weren’t allowed to smoke. He said he tried it himself but only succeeded in burning his eyebrow, therefore we should do it together. He even found a perfect place: between bookshelves, and suggested we go and try it immediately. But I was not used to doing things secretly, and I was always sure of my father’s understanding and support in this. I asked Leonid to wait until the night, when he came home. Leonid agreed, but only until the night. I impatiently waited my father came home and, barely letting him take his coat off, came up to him under pretense of injustice: “You smoke, but don’t let us!” He paused for a moment and asked: “Have you tried already?” I said no, but that Leonid had. Father said: “You are right, we’ll smoke together tonight, just wait until I finish dinner”. He went to eat in my grandmother’s room, where by now the whole family gathered, and I ran with the shocking news to Leonid. When the two of us burst into the room, my father was drinking tea, while everyone else was sitting by the table or stove, discussing, as usual, the days events. Me and Leonid sat down on either side of Lev Semenovich, and began to wait. He soon finished his tea, and took out the cigarettes giving one to me and one to Leonid. Suddenly everyone in the room went quiet and began to watch us intensely.

He was in no hurry, packing the cigarettes, all the while showing how its done and why its necessary. He then demonstrated how to hold the cigarette in the hand and in the mouth. Finally he lit his, took a drag and brought the lighter to ours. Everyone around us was watching his actions, but not interfere with what was going on. “And now, take a deep breath” – said father. I don’t remember much of what happened then, as I almost passed out and got sick. I think Leonid experienced the same reaction. I guess I should add that I never tried smoking again, and Leonid did not try again until he was over 18.

There is one more thing that happened that I will recount. It’s still unpleasant to talk about it, but it happened and it taught me a lesson for life. By now I was in school. I remember it was late May. In class we had an important final coming up. I had a very serious attitude toward it, and was rather anxious. It so happened that I did well on the exam and got a high mark. I returned home in high spirit and was doubly over joyed: my father was home! When he asked me what was new in school, I proudly told him of my success, and added with ill-concealed pleasure that the girl sitting next to me could not copy from me as I had turned the page of the notebook, and because of this got a poorer grade than me. I was beaming and expecting praise, looked at father. I was surprised at the expression on his face: he looked very disappointed. I could not understand what was wrong. May be he did not realize I passed? After a short silence he began to speak, slowly and deliberately so I would remember everything he said. He told me that it was not nice to be happy of others misfortunes, that only selfish people enjoyed it. He went on saying that I should always try to help those who need it, and its only for those who help others that the life is rewarding and brings true joy. I remember I was very upset from his words and asked what I should do now. As always in these situations he offered me a solution: he did not want me to feel like once I did something wrong I was now incapable of doing good. He suggested to me that I go and ask my classmate about what she didn’t understand, and try to patiently explain it to her, and if I couldn’t do it so she would understand perfectly, then he would be glad to help me. “But here is the most important thing”, he added, “you must do all this so your friend be sure you really want to help her, and really mean her well, and so it would not be unpleasant for her to accept your help”. More than 60 years have passed since this incident and I still remember all of his words and try to follow them as best I can in life.

* * *

I don’t believe that “after death there is nothing else”. After his death, the person continues his life in memories of those who loved him and in his works. And so Lev S. Vygotsky lives in the memories of those few, still alive, who know him, and most of all, in his writings that, thanks God, are finally available to everyone. As far as his students go…, well, many of them became famous scientists. Luckily, many were granted a long life. But despite their graying heads and elevated scientific status each has reached, they all still consider the 37 year old researcher their teacher. This was something they never got tired of talking about, and always with great love. Now many are gone, but their students, and now even their students’ students go on. And so science develops. Even though so many years have passed, Vygotsky’s thoughts, ideas, and works not only belong to history, but they still interest people. In one of his articles, A. Leontiev wrote of Vygotsky as a man decades ahead of his time. Probably that is why that he is for us not a historic figure but a living contemporary.

Full Article

A Class Above

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Jeevani Fernando

We sat nervously huddled on the wooden bench of the Haputale Railway Station at 8pm last night, clutching our precious collections from the trip – kithul jaggery from Badulla and jars of orange marmalade, guava jelly and Nelli syrup from Adhisham for the two grandmothers.? Partly shivering in the cold, partly wondering how we were ever going to make the 10-12 hour journey back home by getting in to a train from a midway station with no previous booking.? We had taken a break on the way back to Colombo to visit the beautiful monastry Adhisham and didn’t realise the train will be full by the time it comes to Haputale.

“I love all kinds of people mummy, but I just can’t travel 3rd class on the train” said Mishka. We had just that morning taken 3rd class tickets from Badulla to Haputale and it was quite an experience when, after having paid for 4 seats, we were down to one, when Samaritan love overtook us and we gave seats to mothers with babies and grandmothers, also with babies in the hope of getting a sympathetic seat in an already overcrowded train. Mishka was miffed that people could assume we would feel sorry.?Little realising we were going to need that same sympathy soon.

I said let’s pray. Zoe said let’s throw some people out. Kyle said ‘don’t worry mummy, something will work out’.?15 more minutes to go for the train to arrive. I looked at my 3 fellows and thought I must do something. They had been such good troopers, climbing up and down mountains, trekking nearly 2kms in Indian sandals (bad preparation by the mother) to see and touch the Dunhinda falls, that majestically fell 190ft down creating a mystical cloud of spray and awe.?They had eaten noodles for breakfast and fried rice with no meat as it was the Buddhist festival where no meat was cooked.? They had slept in a mud cabin in the woods and no neighbouring lights, with absolutely no fear at all.?They had been thrilled at every little thing, the train rides through tunnels and around the mountains, the fiery short-eats and even the ghastly toilet in the train where they could see the tracks while doing their ‘little jobs’.

So I plucked my courage and told my three, ‘let mummy go talk to the station master’. The man at the counter had refused to even issue 3rd class tickets to us as he wasn’t sure if there would be room even to stand ‘all other seats FULL madam’ he had said a while ago.? So I by-passed him and walked into the station master’s office.? I made polite introductions in English and he asked what I was doing in Haputale and what had I seen, etc, etc. Then he asked me the wrong question ‘Are you Tamil or Sinhala?’ ‘Oh no!’ says Mishka, because she knows the tirade her mother goes into when that question is asked.? So I let him have it – about how this country got into this state because of questions like that.?And I thought, there goes any chances of getting seats.? Yet,?he didn’t seem peeved. He was in fact making very good conversation.? It ended with his promise ‘I will somehow get you seats but first get yourself on the train with 3rd class tickets’.?I saw Mishka’s face fall.

The train came. It was a mad rush. We managed to scramble into 3rd class. It was packed. It smelled of alcohol and it had no room even on the floor.? I was dismayed but was determined to take it.?I had just managed to put the bags up on the rack when the station master, uniform, cap and all, came running to our compartment and hurried us to take our bags and get off the train. The children groaned. We got off.? He signaled to a man in uniform where the reserved seats were and held up 4 fingers.? We were like refugees now running to the front of the train with bags and jackets and Ivndian slippers flapping under our feet. Passengers poked their heads out to see what was going on with the station master who was also running along with us. The engine driver was getting impatient.? A quick exchange between the two men and we were bundled into 2nd class reserved compartments.? Reclining chairs and all. All I could do was jump back down and shake hands with the station master and thank him profusely.? And as the train pulled away, he shouted ‘I don’t know why I did this but certainly not because you are a Tamil!’

I fell back on my seat laughing. Apparently some others had to be re-arranged to another compartment to fit us in there.? The children were giving hi-five’s to each other. Mishka had found a new hero – a tall, smart station master in Haputale. She was all starry-eyed. I was speechless.? The kindness people show others, in any dimension, makes such a difference to an individual, a family.? Never should one shy from going that extra mile, lending a hand or seeing to the comfort of another, to a strange mother with three children who believed in miracles.? The children will never forget this experience and also the belief that people in their country are helpful, kind and generous no matter what ethnicity they belong to.

And as the knight in shining armour blew the whistle, and Zoe cuddled up to me on the seat, happy she didn?t have to throw anyone out the window, I looked forward to the future of my children.

Coping With Life

Practical session under a banyan tree on the banks of the river Mahananda, Chapainawabgonj. ? Reza/Drik

Practical session under a banyan tree on the banks of the river Mahananda, Chapainawabgonj. ? Reza/Drik

?Kamera tulen?. Elsewhere, one would think a hundred times before pointing a camera. Permission, legality, issues of representation, all came into play. In any Bangladeshi village, getting people out of your lens is the problem. A cluster of heads surround the LCD. Peals of laughter. Old toothless smiles, a little baby held up so she can see. The disappointment of being left out. There might be serious issues to be dealt with, but right now being photographed was all that mattered.

Fourteen-year-old Rabeya, a member of our adolescent group, was taking photos in this beautiful location. I want everyone to live in such a beautiful environment. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Fatema Akter Hasi; 14

Fourteen-year-old Rabeya, a member of our adolescent group, was taking photos in this beautiful location. I want everyone to live in such a beautiful environment. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Fatema Akter Hasi; 14

Trainees from?Barguna. ? Jeevani Fernando

Trainees from?Barguna. ? Jeevani Fernando

With every intervention, one has concerns. Entering people?s lives, creating expectations, making friends, all have to deal with the disengagement that follows. It was people you were dealing with. How do you walk out of a life you have changed, perhaps forever? What do you leave behind, how much do you take away? These were difficult questions and we didn?t really have answers. But we?d tried it before, in cities and in villages. The remarkable transformations it had made to some children?s lives made the risk worth taking.

This is Shorifa Begum on her wedding day in Taherpur. She is a bride at eighteen years old. Shorifa did not want to get married. She stopped her education because she could not afford to continue it. Then her mother forced her to get married to a man who agreed to have a cheap wedding ceremony. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ??Morium Khatun; 16

This is Shorifa Begum on her wedding day in Taherpur. She is a bride at eighteen years old. Shorifa did not want to get married. She stopped her education because she could not afford to continue it. Then her mother forced her to get married to a man who agreed to have a cheap wedding ceremony. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ??Morium Khatun; 16

Md. Moinuddin training in Jamalpur. ? Aminuzzaman/Drik

Md. Moinuddin training in Jamalpur. ? Aminuzzaman/Drik

There were aesthetic concerns too. In talking of composition, rules of thirds, moments, balance, were we suppressing their spontaneity? Did we impinge upon their way of seeing? Were we erasing their natural ability to tell stories? We needn?t have worried. Sure, they tried things out. Pictures were created with remarkable composition. Balanced frames with well-placed elements formed stylised images that a trained photographer would have been proud of, but we had underestimated their instincts. Our fears of over intrusion were unfounded. The most striking images resulted not from our training, but because they had a voice. They could now tell their own stories and no one was going to get in their way, not even their teachers. The proud, chest-out, stiff at attention pose, that thwarted every photographer looking for something ?natural? was very much part of that expression. The loud coloured d?cor that would embarrass the urban genteel, was shown off with panache. Quirky images of everyday scenes, seen the way only children see, were the nuggets that glittered through our light box.

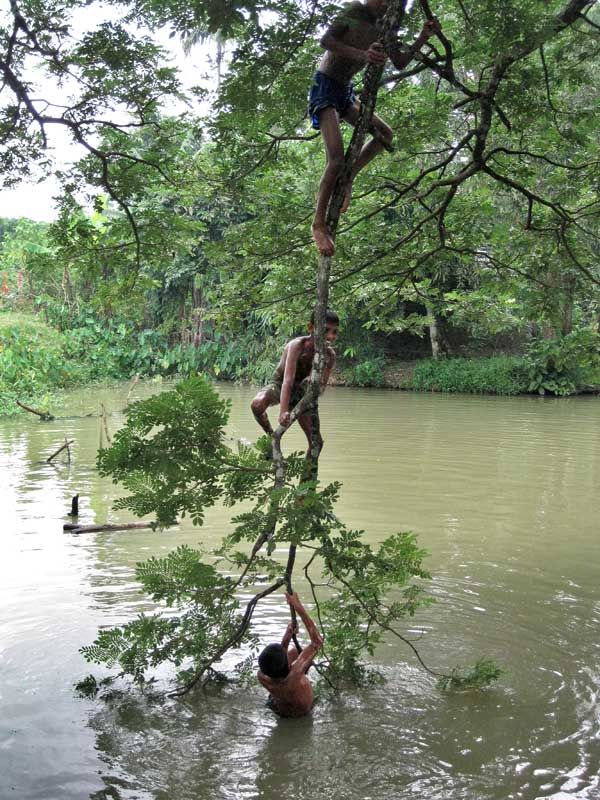

A group of children play in a local pond by climbing onto the tree and jumping into the water. They don’t go to school as their fathers are rickshaw pullers and do not earn enough to educate them. The parents are also not fully aware of the value of education. Barguna, 2009. ??Mohammad Jashim Uddin; 18

A group of children play in a local pond by climbing onto the tree and jumping into the water. They don’t go to school as their fathers are rickshaw pullers and do not earn enough to educate them. The parents are also not fully aware of the value of education. Barguna, 2009. ??Mohammad Jashim Uddin; 18

This is my uncle Shahidul’s goat. Every evening my uncle plays with the goat by holding up a leafy branch for him to jump up and eat. I watched this and took a photo. I also think that if the goat could become a human, then it might not need to jump like this. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ? Md. Sala-uddin Ahmed; 16

This is my uncle Shahidul’s goat. Every evening my uncle plays with the goat by holding up a leafy branch for him to jump up and eat. I watched this and took a photo. I also think that if the goat could become a human, then it might not need to jump like this. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ? Md. Sala-uddin Ahmed; 16

There were quiet reflective moments too. Their realities, the every day challenges, the matter of factness with which they dealt with hurdles, had an immediacy that would humble a trained professional. Layered between romantic images in fields of Kash, looming clouds over flowing rivers, coiled branches silhouetted against stormy skies, were photographs that talked of strife. People less able who insisted on being able. Children longing to be children. A much too young bride. Another young mother to be, gingerly treading through a treacherous path. Absent are the images they were not allowed to show. That threatened a patriarchal society?s image. Pictures they had been forced to delete. Pictures they had staged, as their reality was being suppressed. To delete, to stage, to deal with censorship. These are things they hadn?t been taught. They were learning on the fly. Dealing with situations as best as they could. They were coping with life. Perhaps the ultimate lesson.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

This woman is removing paddy from the basket after it is boiled. She keeps her feet on a jute bag so that they don’t get burnt. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

This woman is removing paddy from the basket after it is boiled. She keeps her feet on a jute bag so that they don’t get burnt. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

Nature photographer. ? Reza/Drik

Nature photographer. ? Reza/Drik

Sohel, 12, lives in Nandina and works in Mostafa Bakery making biscuits and other snacks. He helps his family with his daily wages. It amazes me that a young boy like Sohel has to work for a living instead of going to school. I do not want any child to work for a living. We have to create awareness among people about child labour. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Md. Amir Hossain Apon; 14

Sohel, 12, lives in Nandina and works in Mostafa Bakery making biscuits and other snacks. He helps his family with his daily wages. It amazes me that a young boy like Sohel has to work for a living instead of going to school. I do not want any child to work for a living. We have to create awareness among people about child labour. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Md. Amir Hossain Apon; 14

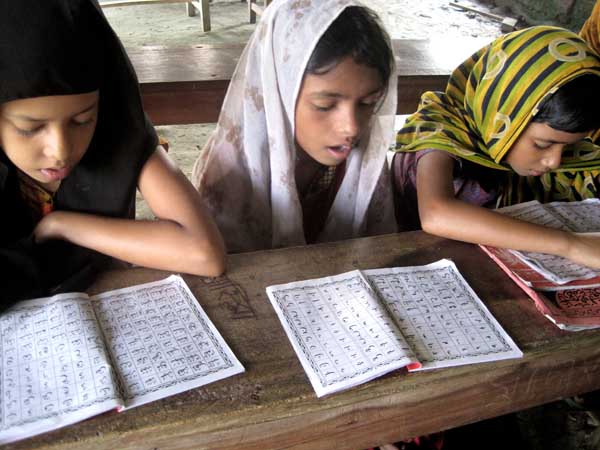

Amy and Rumi are 11 and 12 years old. They go to the madrasa to learn Arabic every morning. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

Amy and Rumi are 11 and 12 years old. They go to the madrasa to learn Arabic every morning. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

Today in Gaza

You who are silent

You who leave it to others

You who do not hear the screams

Every bomb that falls

Every ‘call for restraint’

Every blood clot etched in the sand

Calls out in vain

Calls out in pain

Calls out your name

Remember you let it happen

Remember you turned away

Remember you were silent

————————————————-

This letter arrived this morning:

Dear Shahidul

This is from my friend Selim, about yesterday’s aggression. As you know I worked on year in Gaza (as the head of the UNRWA health services that provides primary health care to 20,000 refugees daily. So far more than 200 dead and more than 700 wounded, many civilians as there is no “clean” war in urban settings and surgical strikes; The horror is there. And foreign governments recommend restraints on both sides as if it was a solution. Hamas respected the truce for many months and saw no improvement.

Thanks for doing what you can.

Pierre Claquin

———————————————-

Today in Gaza

It was just before noon when I heard the first explosion. I rushed to my window, barely had I looked out when I was pushed back by the force and air pressure of another explosion. For a few moments I didn’t understand, then I realized that Israeli promises of a wide-scale offensive against the Gaza Strip had materialized. Israeli Foreign Minister, Tzpi Livni’s statements following a meeting with Egyptian President Hussni Mubarak the day before yesterday had not been empty threats after all.

What followed seems pretty much surreal at this point. Never had we imagined anything like this. It all happened so fast but the amount of death and destruction is inconceivable, even to me and I’m in the middle of it and a few hours have passed already passed.

6 locations were hit during the air raid on Gaza city. The images are probably not broadcasted in US news channels. There were piles and piles of bodies in the locations that were hit. As you looked at them you could see that a few of the young men are still alive, someone lifts a hand here, and another raise his head there. They probably died within moments because their bodies are burned, most have lost limbs, some have their guts hanging out and they’re all lying in pools of blood. Outside my home, (which is close to the 2 largest universities in Gaza) a missile fell on a large group of young men, university students, they’d been warned not to stand in groups, it makes them an easy target, but they were waiting for buses to take them home. 7 were killed, 4 students and 3 of our neighbors kids, young men who were from the same family (Rayes) and were best friends. As I’m writing this I can hear a funeral procession go by outside, I looked out the window a moment ago and it was the 3 Rayes boys, They spent all their time together when they were alive, they died together and now their sharing the same funeral together. Nothing could stop my 14 year old brother from rushing out to see the bodies of his friends laying in the street after they were killed. He hasn’t spoken a word since.

What did Olmert mean when he stated that WE the people of Gaza weren’t the enemy, that it was Hamas and the Islamic Jihad who were being targeted? Was that statement made to infuriate us out of out state of shock, to pacify any feelings of rage and revenge? To mock us?? Were the scores of children on their way home from school and who are now among the dead and the injured Hamas militants? A little further down my street about half an hour after the first strike 3 schoolgirls happened to be passing by one of the locations when a missile struck the Preventative Security Headquarters building. The girls bodies were torn into pieces and covered the street from one side to the other.

In all the locations people are going through the dead terrified of recognizing a family member among them. The streets are strewn with their bodies, their arms, legs, feet, some with shoes and some without. The city is in a state of alarm, panic and confusion, cell phones aren’t working, hospitals and morgues are backed up and some of the dead are still lying in the streets with their families gathered around them, kissing their faces, holding on to them. Outside the destroyed buildings old men are kneeling on the floor weeping. Their slim hopes of finding their sons still alive vanished after taking one look at what had become of their office buildings.

And even after the dead are identified, doctors are having a hard time gathering the right body parts in order to hand them over to their families. The hospital hallways look like a slaughterhouse. It’s truly worse than any horror movie you could ever imagine. The floor is filled with blood, the injured are propped up against the walls or laid down on the floor side by side with the dead. Doctors are working frantically and people with injuries that aren’t life threatening are sent home. A relative of mine was injured by a flying piece of glass from her living room window, she had deep cut right down the middle of her face. She was sent home, too many people needed medical attention more urgently. Her husband, a dentist, took her to his clinic and sewed up her face using local anesthesia

200 people dead in today’s air raid. That means 200 funeral processions, a few today, most of them tomorrow probably. To think that yesterday these families were worried about food and heat and electricity. At this point I think they -actually all of us- would gladly have Hamas sign off every last basic right we’ve been calling for the last few months forever if it could have stopped this from ever having happened.

The bombing was very close to my home. Most of my extended family live in the area. My family is ok, but 2 of my uncles’ homes were damaged. We can rest easy, Gazans can mourn tonight. Israel is said to have promised not to wage any more air raids for now. People suspect that the next step will be targeted killings, which will inevitably means scores more of innocent bystanders whose fate has already been sealed.

This doesn’t even begin to tell the story on any level. Just flashes of thing that happened today that are going through my head.

Peace

Selim

———————

Identity Card, a poem by Mahmoud Darwish

gaza-holocaust-report

gaza-violence-attracting-people-to-citizen

Happy?s New Year

My first podcast

?No one ever comes back,? she said. She was baleful, half a tear welling on her eyes. I had no way of knowing when I might be back. I hugged her tight as she sat on my lap, but my words were not convincing. She had been promised many times before and knew not to be too wishful. The name ?Happy? seemed a difficult one to use to describe her. Yet minutes before Happy Akhter Nodi and I had been playing, laughing, teasing one another. She was probably around 10. She didn?t really know, and I couldn?t really tell.

Her mother had brought her over to the Sonar Bangla Children?s home three years ago. Happy had wanted to come herself. She wanted to study. To become a doctor. To serve people. But parting had been sad. Her mother had come to see her on previous new year days, but this time she?d rung to say she couldn?t make it. There was too much work over the holidays. Happy understood, but it didn?t make it any easier. She wanted to go to the fair, to buy toys, to dress up in a new sari. She wanted her mum. Happy was spunky, bubbly, naughty, and dying to be loved. I tried to tell her that her mother might come another day. We both knew I was pretending.

She was being protective of me. Making sure the other kids didn?t hassle me too much. She became my self appointed muse. The poem by Kazi Nazrul I was trying to sit and translate wasn?t easy and they were all impatient. There was a children?s poem in the book, which she remembered from school, but even that didn?t hold her attention. We both knew I would be leaving soon. The sun was coming down and I was waiting for that sweet light when I would photograph Putul (an older girl in the home) in the green paddy fields. I was there on an assignment, and needed to get back to work. I would then go back to Dhaka, and perhaps out of her life for ever.

?You will ring tomorrow, or I?ll never talk to you again.? This had been the biggest threat we knew as children. ?I?ll never talk to you again.? I nodded, not trusting myself to speak. It would be new year?s day, and it gave me some chance to make amends. She snuggled up to me and said, ?You have to give me a name. One just for us.? Despite her sadness, the name Happy had seemed very apt. She was a happy child. They must have given her the name knowingly. Her mother?s name Adori Begum, had also perhaps been a name she had been given. A woman who provided love. When I?d photographed Happy before, she was being her mischievous self. She?d put on a shawl around her head and looked much older than she was. Now she looked smaller than her age, and very fragile.

As the light went down, we went to the paddy fields together, holding hands all the way. Happy jealously warding off the other kids. The light was beautiful and Putul glowed in the green paddy. Then it was time to go. As we walked back she guided me through the bracken, protecting me from every thorn. As we came to a clearing, she looked me over and untangled a rubber band dangling from my pouch. It was a worn band, left over from an old baggage tag at some airport. ?I?ll keep this,? she said. ?Now, give me my name.? I whispered back ?Anmona?. It was all I could think of. This wistful girl, with the bright eyes, full of sadness, suddenly seemed so far away.

We said our goodbyes and as all the children rushed to hug and kiss and wave goodbye, Happy stayed back. Silently she repeated the word ?Anmona?. As the car moved out of the gate I could see her through the dust. She was holding on to a worn ragged baggage tag.

1st Baishakh 1414

Bangla New Year’s Day

Boxing Day Blues

When Jolly’s son Asif asked me to take a portrait of him and his new bride Rifat, I took it on with grandfatherly pride. The photo session was booked for Sunday morning, the 26th December 2004. Boxing day.

The envelope from Sri Lanka also arrived on Boxing Day. 2006. Priantha and his daughter Shanika had sent me Christmas greetings. I felt bad that I had not sent them one.

I used to love the winding path up to the hilltop house in Chittagong. Zaman Bhai was the chief engineer of the Chittagong Port Trust. One of the few Bangalis in high positions in 1971. It is thirty five years since the Pakistanis took him away, but even many years after liberation, my cousin Tuni Bu would still look for him. Anyone going to Pakistan would be given the task of trying to find out if there was any knowledge of where he might have been taken, what might have happened. One knows of course what must have happened, and I am sure Tuni Bu knows too, but that never stopped her from trying to find out. She was much older than me, and it was my nephews Bulbul and Tutul and my niece Jolly, that I was close to. Atiq was too young in those days to qualify for our friendship. The house had a fountain and the surrounding pool was our swimming pool. It was the only home I had ever known that had a pool. Technically I was of granddaddy status to Jolly’s son, and the young man reminded me of my own happy childhood.

While I played around with the studio lights, Asif told me of the Richter 9 earthquake that had hit Bangladesh. Of course I didn’t believe him. Richter 9 is big and there simply couldn’t have been an earthquake of such magnitude without anyone registering it. But I did turn on the news immediately after the portrait session, and the enormity of the disaster slowly sank in. I rang Rahnuma and asked her to turn on the television, and went back to work. By then however, the news of the carnage in places thousands of miles away started coming across the airwaves.

The next day the numbers steadily rose from the hundreds to thousands and we were glued to the set. Though we hadn’t said it out aloud to each other, both Rahnuma and I knew I had to go. BRAC had organized a training for women journalists in their centre in Rajendrapur on the 28th. I had committed myself to the training some time ago and couldn’t really bail out in the last minute. On the way I heard from Arri that my friend in Colombo Chulie de Silva was missing. I kept losing the signal on my Grameen mobile phone on my way to and from Rajendrapur, but near Dhaka I managed to get text messages through. Chuli was safe, but her brother had died.

Babu Bhai managed to get me a flight the next day via Bangkok. I had posted an angry message in ShahidulNews in response to the tourist centric reporting in mainstream media and many friends responded. Margot Klingsporn from Focus in Hamburg wired me some money. Not waiting for the money to arrive, I gathered the foreign currency I could lay my hands on, packed a digital camera and a video camera along with my trusted Nikon F5 and left. That was when I made friends with Shanika.

http://www.zonezero.com/tsunami/shahidul/article.html

It was Chulie who helped trace her. She had heard my story and wrote to me that she had found a “Shanika Cafe” near Hikkaduwa. We had gone out together in search of the girl. When we did find Shanika and her dad Priantha, she rushed to my arms.

Through Chulie’s translations Priantha told me that Shanika had been withdrawn and wouldn’t relate to people. It was our friendship that had brought out the little girl.

More than the wreckage and the rotting flesh,

I remember the mother in the refugee camp stealing a kiss from her new born child.

I remember the family sitting in the wreckage of their home in Hikkaduwa, going through the family album.

I remember the devotees returning to the Shrine of Our Lady of Matara Church to pray.

As a photojournalist we are touched by, and touch many people’s lives. Sometimes – not often – we are able to make a difference. But invariably we move on. On to another disaster, another success, another story in the making. The Shanikas of our stories, become yet more stepping stones in our career path, and the Christmas cards flow only in one direction.

Shahidul Alam

28th December 2006

Doing What I Do

Why do I do what I do? I know how I started, partly by accident, when I got stranded with a camera I had bought for a friend, but that in itself cannot explain the joy, the passion, the amazing high that I get when I see something magical in my frame. So I’m a photojournalist. Like so many others who started off in this noble profession, I too believed I was going to change the world through my images. It took a while for reality to settle in. A while to know, that taking good pictures wasn’t enough. There were gatekeepers who decided which pictures would get used, and how they might be used, and the gatekeepers generally didn’t share my ideology or passion.

It was children who shaped my visual world. Initially, as a photographer in London, I would go round asking adults with children, if I could take portraits of their kids. Some would agree, and I would go over to their homes, put down my synthetic sheepskin rug, get the kids to smile at my camera and take happy pictures. If things went well, they would buy some pictures, and we would all be happy. Not the ultimate in photography, but it paid the bills, and helped me save some money that I thought would allow me to start afresh back home.

In Bangladesh, the children had been swapped for a new range of subjects. Ice cream and plastic toys, the odd glamour shot, some celebrity. Ceramics and fancy machines. I photographed the lot. It was as an activist, in our attempt to remove an autocratic leader, that my camera finally knew what it wanted. With the adrenaline flowing as we marched through the teargas, my camera learned to love the smell of the streets. We braved the curfew, to photograph the courage of a people and the tyranny of a tyrant. I never got a picture published in those days, as a democracy movement in the majority world, was simply not news. A flood or a cyclone was much more interesting. But when we eventually forced the dictator to step down, I photographed the rejoicing, and later at our long awaited election, I photographed a woman casting a vote. When we put up the images for an impromptu exhibition, over 400,000 people came to our three day show.

But international media wasn’t interested, and it wasn’t till the cyclone in 1991, that they started asking for images again. The same western photographers came over at the first smell of disaster, and went back with the same helpless images, reducing a proud people to icons of poverty. Even locally, the images we produced and the words we wrote, seemed to have little effect. This powerful tool that I thought I’d picked up, suddenly felt blunt in the face of corruption and indifference.

That was when, while talking to a group of working class children I was training, I was shaken. Sitting on the school verandah, 10 year old Moli, looked at the photograph of the bodies of children being dragged. ?O that was the fire in number 10? she said.

“How do you know?”

“Everyone knows.”

“What happened?”

“Nothing ever happens.”

Then she waits a bit, and says, “If I had a camera, I’d take his picture and put that guy in jail.”

It was the conviction of that 10 year old girl, that fired me up again. I remembered a moment six years ago, during a flood, where children who had taken shelter in a warehouse, insisted that I take a picture of them. As they stood by the large open window, all proud and standing at attention, I noticed that the boy in the centre was blind. He stood with his chest out, pushing back the other kids. Staring straight out at the camera he couldn’t see for the photograph he would never know. I began to realise how much more important the photograph was than simply my weapon for change. It represented hope and belief and could give a sense of dignity to many.

My photography slowly changed, as did the world around me. I began to see things that had never existed before. People mattered in a way that they hadn’t mattered before. The man in our neighbourhood, who collected the garbage late at night, pushing his cart in the rain, gathering each scrap of paper that he could sell to keep his family alive, took on a stature of enormous proportions. I wanted my camera to do what Moli and that blind boy had willed it to do. I wanted my camera to befriend the man with the cart. I felt ashamed, I had never stopped to ask his name.

It was at about that time that I met Abdul Malik, on an Aeroflot plane bound for Tripoli. He dreamt of somehow changing his destiny, and I dreamt of somehow documenting his dream. I have never met Abdul Malek since, and I don’t know if came back home and bought the piece of land he hoped to buy, and whether he was able to arrange a marriage for his sister, but I have seen that dream in many eyes. When the very things that the wealthy aspire to, becomes part of a migrant’s dream, the dream becomes illegal. I want my images to challenge that illegality, and all the illegalities that are sprouting around us. The illegality of a right to a homeland, the illegality of protest against oppression. The illegality of wanting a better life. I want to photograph Moli’s dream and that of the blind boy and the man with the cart.

Shahidul Alam

17th August 2003