![]()

Year end play: The Nuculier God

Theatre: The World

Set Design: Tony Blair

God: George Bush

Sacrificial Lamb: Saddam Hussein

Slaves: Saudi Royal Family and cohorts

Extras: The United Nations

Theme song: I can kill any Muslim

I can kill any Muslim

Any day I choose

It?s all for the cause of freedom

I can kill any Muslim

Wherever I choose

It is cause we?re a peace lovin? nation

So we egged him on

When he attacked Kuwait

And the trial may have been harried

So we supplied him arms

To gas the Kurds

With him dead, that?s one story buried

Violence in Iraq

Has been on the rise

The US can hardly be blamed

Our interest was oil

And we stuck to our goal

Why must my cronies be named

Saddam?s emergence

As Arab resistance

That wasn?t part of the plan

Had Amnesty and others

Kept quiet when it matters

We?d have quietly gone on to Iran

Asleep I was

When he hanged on the gallows

Well even presidents need to sleep

Oblivious I was

When the planes hit the towers

I had other ?pointments to keep

More Iraqis dead

More ?mericans too

OK they warned it would happen

Why should I listen

When I rule the world

No nation?s too big to flatten

The Saudi Kings

They know their place

At least they?ll know by now

Muslim?s OK

If you tow the line

Out of step, off you go, and how

Tony and me

We keep good company

Dictators know when it matters

Regardless of crimes

And religious inclines

Safe if you listen or its shutters

I can kill any Muslim

Wherever I choose

I choose quite often I know

I can kill any Muslim

Any day I choose

I did it so now they will know

Similar to Rumsfeld’s concern that the Abu Ghraib pictures coming out, and not about the events themselves, the Iraqi government worries about the footage of Saddam being taunted, getting out. The fact that the taunting took place doesn’t appear to be an area of concern. With the US government stifling Al Jazeera, and increasing censorship in mainstream media, citizen journalism appears to be the only way people can get past the PR camouflague.

With all political parties of Bangladesh, as well as most Muslim leaders around the world, choosing to remain silent at the execution of Saddam Hussein, it is left to human rights organizations to remind us, that despite his atrocities, Saddam will be remembered for his defiance. The butcher of the Kurds will go down in history as a victim of flawed justice. The guns are now clearly turned against Iran, but the Saudi rulers, as well as the Egyptians and the Jordanians would do well to ponder, ?Who is next??

Category: media

Boxing Day Blues

When Jolly’s son Asif asked me to take a portrait of him and his new bride Rifat, I took it on with grandfatherly pride. The photo session was booked for Sunday morning, the 26th December 2004. Boxing day.

The envelope from Sri Lanka also arrived on Boxing Day. 2006. Priantha and his daughter Shanika had sent me Christmas greetings. I felt bad that I had not sent them one.

I used to love the winding path up to the hilltop house in Chittagong. Zaman Bhai was the chief engineer of the Chittagong Port Trust. One of the few Bangalis in high positions in 1971. It is thirty five years since the Pakistanis took him away, but even many years after liberation, my cousin Tuni Bu would still look for him. Anyone going to Pakistan would be given the task of trying to find out if there was any knowledge of where he might have been taken, what might have happened. One knows of course what must have happened, and I am sure Tuni Bu knows too, but that never stopped her from trying to find out. She was much older than me, and it was my nephews Bulbul and Tutul and my niece Jolly, that I was close to. Atiq was too young in those days to qualify for our friendship. The house had a fountain and the surrounding pool was our swimming pool. It was the only home I had ever known that had a pool. Technically I was of granddaddy status to Jolly’s son, and the young man reminded me of my own happy childhood.

While I played around with the studio lights, Asif told me of the Richter 9 earthquake that had hit Bangladesh. Of course I didn’t believe him. Richter 9 is big and there simply couldn’t have been an earthquake of such magnitude without anyone registering it. But I did turn on the news immediately after the portrait session, and the enormity of the disaster slowly sank in. I rang Rahnuma and asked her to turn on the television, and went back to work. By then however, the news of the carnage in places thousands of miles away started coming across the airwaves.

The next day the numbers steadily rose from the hundreds to thousands and we were glued to the set. Though we hadn’t said it out aloud to each other, both Rahnuma and I knew I had to go. BRAC had organized a training for women journalists in their centre in Rajendrapur on the 28th. I had committed myself to the training some time ago and couldn’t really bail out in the last minute. On the way I heard from Arri that my friend in Colombo Chulie de Silva was missing. I kept losing the signal on my Grameen mobile phone on my way to and from Rajendrapur, but near Dhaka I managed to get text messages through. Chuli was safe, but her brother had died.

Babu Bhai managed to get me a flight the next day via Bangkok. I had posted an angry message in ShahidulNews in response to the tourist centric reporting in mainstream media and many friends responded. Margot Klingsporn from Focus in Hamburg wired me some money. Not waiting for the money to arrive, I gathered the foreign currency I could lay my hands on, packed a digital camera and a video camera along with my trusted Nikon F5 and left. That was when I made friends with Shanika.

http://www.zonezero.com/tsunami/shahidul/article.html

It was Chulie who helped trace her. She had heard my story and wrote to me that she had found a “Shanika Cafe” near Hikkaduwa. We had gone out together in search of the girl. When we did find Shanika and her dad Priantha, she rushed to my arms.

Through Chulie’s translations Priantha told me that Shanika had been withdrawn and wouldn’t relate to people. It was our friendship that had brought out the little girl.

More than the wreckage and the rotting flesh,

I remember the mother in the refugee camp stealing a kiss from her new born child.

I remember the family sitting in the wreckage of their home in Hikkaduwa, going through the family album.

I remember the devotees returning to the Shrine of Our Lady of Matara Church to pray.

As a photojournalist we are touched by, and touch many people’s lives. Sometimes – not often – we are able to make a difference. But invariably we move on. On to another disaster, another success, another story in the making. The Shanikas of our stories, become yet more stepping stones in our career path, and the Christmas cards flow only in one direction.

Shahidul Alam

28th December 2006

Judge on the docks

![]()

?Come out we won’t shoot?, they had yelled out over the megaphone. Not the most alluring of invitations, particularly when it is from a police van surrounding your flat at midnight. They had thought we were hiding someone and after searching our rooftop had come into our flat. As they left, I had gone out to take pictures from our verandah. Rahnuma had turned up the television volume to hide the sound of the shutter on my Nikon 501, but it still seemed to make a very loud click. Luckily, I wasn?t noticed. It was the 2nd December 1990. Ershad?s autocratic government was feeling the heat.

Two days earlier, after the Friday prayers, they had opened fire on the Baitul Mukarram mosque killing a man.

Lawyers had played an important role in our democracy movement. They had upheld writ petitions against the government, and when the government tried to flex its muscles, they came out in protest, united in their stand.

On this day, exactly sixteen years ago, barrister Shahjahan, Sarah Hossain and other lawyers were meant to meet at Drik. We were monitoring the government action, and were ourselves under scrutiny. My colleagues had warned me that plain clothed detectives were looking for me at the office. The detectives seemed to know we lived in Lalmatia, and my colleagues suggested that we stay elsewhere that night. Ma (Rahnuma?s mum), Rahnuma, Tehmina (a lawyer friend of ours) and I went over to Saif and Rini?s flat in Dhanmondi Rd 8. This was not the time for taking chances. The media too had played their role. When censorship became intolerable, they refused to publish. It was that night that Ershad had announced on television that he was going to step down. People were rejoicing in the streets. The following morning the first newspaper was out.

We all went out into the streets. Altaf on his motorbike, me on my bicycle, and the others in whatever transport they could find.

A little girl walked down Mirpur road with a bouquet of flowers in her hand. She too was celebrating the return of democracy. People were dancing in the streets. In Paltan, too often the scene of violence, people gathered in ones and twos.

Men and women in their sleeping clothes, some with children, gathered in the winter night. Chatpati wallas sensing a business opportunity appeared out of the fog. At about 1:30 am Shimul Billa, Bangladesh’s Shirley Temple, sang out ?Bichar poti tomar bichar korbe jara, aj jegeche ei jonota?.

The song ?O judge, the people have risen, it is now the day of your judgement?, was strangely prophetic.

And now in 2006, the chief justice of the supreme court intervenes to prevent a decision

going against a political party, lawyers ransack the court, a president with zero credibility heads a caretaker government, and of all people, Ershad himself is in the streets, demanding the removal of the current president, while Moudud, the chameleon survivor, then Ershad’s right hand man, now holds hands with the chief justice.

4th December 2006

Delhi

The Campaign Begins

![]()

“We travel to Dhaka, in Bangladesh for a celebration of South East Asian photography thanks to a festival called Chobi Mela, on its fourth edition so far. Their theme this year is ‘boundaries’: ideas, aspects, images that divide peoples and cultures. Perfect backdrop for the violence in the country ahead of forthcoming elections…” http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/programmes/the_ticket.shtml. They did a hatchet job on Anita’s interviews, but at least the BEEB did give coverage to Chobi Mela IV.

Besides Cristobal (asleep on the rickshaw) and Norman, all the others have gone back.

Richard, Wubin and Cristobal, testing out environmentally friendly modes of transport.

Rupert claims his neighbours need sunglasses to cope with his glistening green punjabi from Dhanmondi Aarong.

The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) motorbike cruised slowly past Drik in the morning. Earlier I’d seen them cruise in Gulshan and Baridhara. It was like a scene from Easy Rider, though the ‘crossfire’ victims might not think so. I’ve never seen them in the troubled areas of Paltan, or Muktangon, or anywhere there are clashes between the public and the police. The RAB seem to have different priorities. For the moment at least, the elite force seems only concerned with protecting the elite.

Meanwhile, a Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) takes a strange and undefined ‘leave’, with veiled threats of “I shall return”, and the fighting gives way to election frenzy.

The Police in a different role

The campaigner, a new kid on the block

Hired supporters, a new form of employment

Employment for all

And the inevitable traffic jams

For those trying to avoid the winter chill, the priorities are somewhat different. A girl cooks dinner at Russel Square. Earlier the burning cars provided the flames.

Taking care of the caretaker

It was a dramatic ending to Robert Pledge?s presentation. Via Topu and Omi, I?d received the news that the military had been called out. Robert wanted to finish the presentation, but once I?d announced the government?s decision, the auditorium of the Goethe Institut quickly emptied out. This particular Chobi Mela IV presentation had come to an abrupt end. It was 1987 revisited.

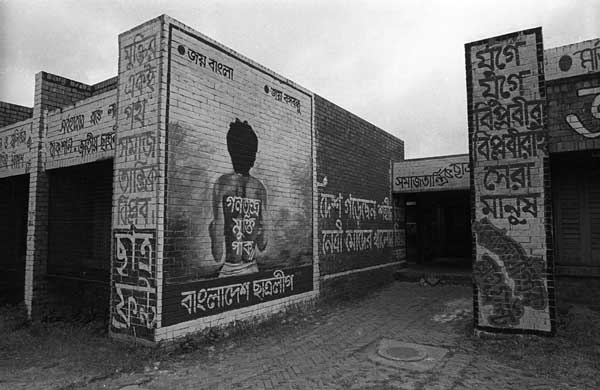

Noor Hossain had painted on his back ?Let Democracy be Freed? and the police had gunned him down on the 10th November 1987. But the people had taken to the streets and while we were scared the military would come out, there was no stopping us. It had taken three more years of street protests, before the general was forced to step down. The people had won. But then it had been a military general who was ruling the country. This was a civilian caretaker government. The general mistrust of a party in power, had resulted in this unique process in Bangladesh where an interim neutral caretaker government headed by a Chief Adviser (generally the most recently retired Chief Justice) and consisting of other neutral but respected members of the public were entrusted with conducting the elections. Why then the military? Yes, the president was a Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP, the largest party in the outgoing coalition government) appointee, there are ten advisors who are meant to be neutral.

A free and fair election hasn?t yielded the electoral democracy we had hoped for. After each term, the people have voted out the party in power, only to be rebuffed by a political system that has never had the interest of the people on their agenda. Still, the elections were held, and despite the fact that there had been one rigged election in 1996 (rejected and held again under a neutral caretaker government), an electoral process of democratisation, was slowly developing.

This time however, the total disregard for the electoral process has created a sham, and the three key people in this electoral process, the president, the chief adviser, and the chief election commissioner (CEC), are colluding against the people. The first two, being represented by the same person, was a BNP appointee. He also happens to be the head of the military. The CEC, now a cartoon character, had also been appointed by the BNP while it was in power. Coupled with a clearly flawed voters list, this has removed any hope of a free and fair election. Can the caretaker government genuinely conduct a fair election? I believe it still can, if given the chance, despite the president?s lack of credibility. But for that to happen, the military, the bureaucracy and the police need to remember that it is with the people that their allegiance lies.

However, it does depend upon the removal of the other obstacles. The election commissioner cannot constitutionally be removed, and his removal is central to the opposition demands. What then can we do? There is only one body higher than the constitution, the people themselves. The advisors need to be empowered if they are to pull off this election. Sandwiched between a partisan executive head and another partisan CEC, the advisers risk becoming irrelevant. The only way this can be checked is if people come out in droves. Not ?hired for the day? supporters but ordinary people committed to civilian rule, and a multi-party system.

It is we the people who need to take to the streets. And it is time we sent out the message to all political parties, that an entire nation cannot be appropriated. They need to be told that we did not liberate our country in vain, and despite the poverty and the hardship that we go through, we will not be cowed down, and will not blindly tow a party line, when the party itself has disengaged from the people. If tomorrow, every woman man and child takes to the street of Bangladesh, there is no power, not the military, not the president, not the advisers, not the CEC, not the BNP and not AL that can stop us.

There is hope yet. The advisers have had the good sense to reverse the home ministry?s unilateral decision to call out the army and the president and chief adviser has been challenged for taking such a step. Whether the advisers can continue to take such bold steps depends on our ability to bolster their nebulous position.

Blockades and hartals do hurt the economy, and ironically, it is the person in the street who is the most vulnerable. But faced with an attempt to take away the only chance she has to exercise her right to elect the government of her choice, she has little option left but to take to the streets. As the world is finding out, in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and wherever else there is conflict, a military victory is never a victory. If the anger of the people is to be quelled, then the underlying causes of discontent need to be solved. Flexing the muscles of the military, will only put a lid on the boiling pot, and the longer the lid is pressed down, the bigger will be the eventual explosion. More have died today, and with every death, the flashpoint looms closer.

Chobi Mela IV has continued despite it all. The dancing in the all night boat party,

the heated arguments at every meeting point, the mobile exhibitions, all went on despite the turmoil. The presentations on the night of the 11th, with Yumi Goto, showing work by the children from Bandar Aceh, Neo Ntsoma showing her work on youth culture in South Africa, Chris Rainier showing his long term projects on ?Ancient Marks?, and the deeply personal, but very different accounts of Trent Parke

and Pablo Bartholomew, made one of the most intriguing evenings I can remember. The packed audience that had braved the blockade had perhaps an inkling of what was to come. Morten had a full house for his ?gallery walk? at the Alliance Francaise and Trent?s workshops were packed out. The grand opening was at the National Museum, where we had one fifth of the cabinet opening the show. Kollol gave a passionate rendering of his song ?Boundaries? written especially for the festival. The rickshaw vans designed to take the festival to the public, plied the streets of Old Dhaka, Mirpur and other areas not used to gallery crowds.

The chief guest, adviser C.M. Shafi Sami, the special guests adviser Sultana Kamal and Robert Pledge, photographers Morten Krogvold and Trent Parke and the scholarship recepient Dolly Akhter all spoke eloquently. Little did the audience know about the drama that had taken place the night before. With the museum functionaries doing their best to keep us from putting up the Contact Press Images show (http://www.chobimela.org/contact_press_images.php), we were under pressure, but working all through the night and sleeping on the museum floor, we managed to put the show up on time.

Last night, the empty streets, looked ominous as I dropped off Chulie, Robert and Yang, and people have been dying in the streets.

Since then we have had Morten Krogvold?s passionate presentation at the gallery walk at Alliance, Rupert Grey?s clinical dissection of the law and his dry British humour,

both at the British Council and the Goethe Institut, Saiful Huq Omi?s disturbing but powerful images of political violence, Cristobal Trejo?s poetic rendering of an unseen world, Richard Atrero De Guzman?s honest response to difficult questions about representation and my own presentation on natural disasters and their social impact have all been well attended, despite the tension in the desolate Dhaka streets. The evening presentations close tonight with an insightful film by Indian film maker Joshy Joseph, presentations by Norman Leslie and a behind the scenes look by the photographers at the Drik Photo Department, Md. Main Uddin, Shehab Uddin and Amin, Chandan Robert Rebeiro, Imtiaz Mahabub Mumit and Shumon of Pathshala and Mexican exhibitor Cristobal Trejo. The shows go on as they always do at Drik.

In 1991, a woman with her vote had avenged Noor Hossain’s death.

A fortnight ago, the city was in flames, and a stubborn chief election commissioner is stoking the flames again. It is a fire he and his allies will be powerless to stop.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

Chobi Mela site

Blog by Australian curator Bec Dean

Short video on Chobi Mela IV

I hear the screams

![]()

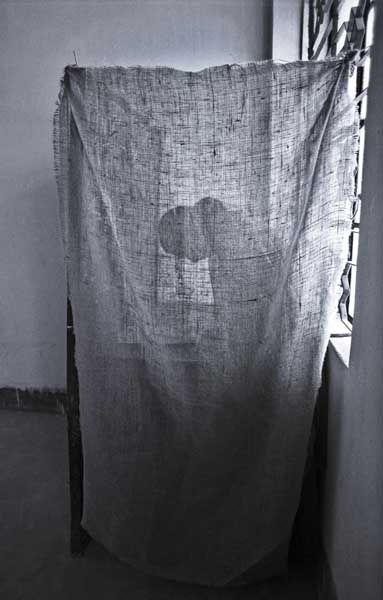

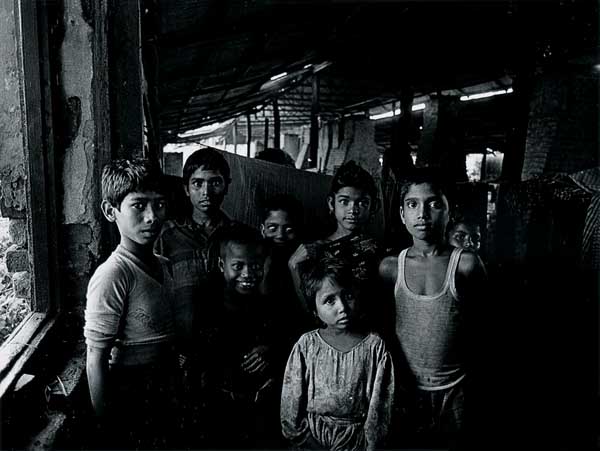

Even after years of playing Pied Piper with a camera, I am still taken aback by children insisting on being photographed. It was September 1988, and we had had the worst floods in a century. These people at Gaforgaon hadn’t eaten for three days. A torn saree strung across the beams of an abandoned warehouse created the only semblance of a shelter. Their homes had been washed away. Family members had died. Yet the children had surrounded me. They wanted a picture.

It was dark in that damp deserted warehouse, but the broken walls let in wonderful monsoon light, and they jostled for position near the opening. It was as I was pressing the shutter that I realised that the boy in the middle was blind. He had pushed himself into the centre, and though he wasn’t tall he stood straight with a beaming smile.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CARE

Clip on story of the blind child, from keynote presentation on citizen journalism at 50th Anniversary of World Press Photo in Amsterdam.

I’ve never seen the boy again, and today I question the fact that I do not know his name. But he has never left my thoughts and often I have wondered why it was so important for that blind boy to be photographed.

It’s happened elsewhere, in boat crossings at the river bank. In paddy fields heavy with grain, in busy market places. A shangbadik (literally a journalist, but in practice any person with a half decent camera) was hugely in demand. They refused to take the fare from me at the ferry ghat. Opened up their hearts and told me their most personal stories. Confided their secrets, shared their hopes. Never having deserved such treatment it has taken a while for me the photographer, to work out why being photographed meant so much to that blind child.

The stakeholders of Bangladeshi newspapers are the urban elite. Consequently stories from the village are about the exotic and the grotesque. Village people exist only as numbers, generally when plagued by some disaster and only when figures are substantial. A photograph in a newspaper, regardless of how token the gesture, is the only time a villager exists as a person. A picture on a printed page would have lifted that blind boy from his anonymity. That humbling thought stays with me whenever I am feted as a shangbadik in some small village. I receive their gift of trust gently, careful not to break the delicate contents.

It was as a photographer of children that I had begun my career. It was way before 9/11 and one could make appointments with strangers and go to their homes. I took happy pictures of kids, and parents loved them. It was easy money, except when I would photograph the children of poor parents. They loved the pictures but couldn’t afford to pay, so I would quietly leave the pictures behind and pay the studio out of my pocket. Back in Bangladesh, the only way I could make money was as a corporate photographer, but something else was happening. We were in the streets, trying to bring down a general who had usurped power. I didn’t know it then, but I was becoming a documentary photographer. Suddenly taking pictures of children meant more than smiling kids on sheepskin rugs.

As the pressure against the general mounted, I photographed children who joined the processions. The night he stepped down, I photographed a little girl with a bouquet of flowers. She was out with her dad in the middle of the night, celebrating the advent of democracy.

I am back in Kashmir eight months after I had been here photographing the advent of winter. The valleys of this fertile land are green with new crops,

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

but many of the homes are still to be rebuilt. As I walked through the rubble, the kids again wanted to be photographed.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Najma came running, her bright red dress popping out of the green maize fields.Unsure at first, she smiled when I told her she had the same name as my sister.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Zaheera, a cute girl with freckles, gathered her friends and sang me nursery songs. But my thoughts are far away. Despite the laughter and the nursery songs very different sounds enter my consciousness. I remember the children screaming on the night of the 25th March 1971, when I watched in helpless anger as the Pakistani soldiers shot the children trying to escape their flame throwers. The US had sent their seventh fleet to the Bay of Bengal, in support of the genocide. Today, as I remember the Palestinians and the Lebanese that the world is knowingly ignoring, I can hear the bombs raining down on Halba, El Hermel, Tripoli, Baalbeck, Batroun, Jbeil, Jounieh, Zahelh, Beirut, Rachaiya, Saida, Hasbaiya, Nabatiyeh, Marjaayoun,Tyr, Jbeil, Bint Chiyah, Ghaziyeh and Ansar and I hear the screams of the children. Piercing, wailing, angry, helpless, frightened screams.

News filters through of the children killed in the latest bombing. The photographs have kept coming in, horrific, sad, and disturbing. Mutilated bodies, dismembered children, people charred to ashes. But none as vulgar as those of Israeli children signing the rockets. Death warrants for children they’ve never known.

I remember my blind boy in Gaforgaon. The Lebanese and the Palestenians are also people without names. Their pain does not count. Their misery irrelevant, their anger ignored. Sitting in far away lands, immersed in rhetoric of their choosing, conjuring phantom fears necessary to keep them in power, hypocritical superpowers fail to acknowledge the evil of occupation. The ‘measured response’ to a people’s struggle for freedom will never in their reckoning allow a Lebanese or a Palestinian to be a person.

When greed becomes the only determining factor in world politics. When the demand for power, and oil and land overshadows the need for other people’s survival, I wonder if those screams can be heard. I wonder if those Israeli children will grow up remembering their siblings they condemned. I wonder if through all those screams the war mongers will still be asking “why do they hate us”?

11th August

Siran Valley, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

Boundaries

Chobi Mela IV

She packed her load of firewood onto the crowded train in Pangsha. The morning sun peered through the lazy winter haze. The vendors called ?chai garam, boildeem? and the train slowly chugged out of the station, people still clambering on board, or finishing last minute transactions. Some saying farewell. The scene had probably not been very different a hundred years ago. Maybe then, they carried pan in place of firewood, or some other commodity that people at the other end needed. She would come back the same day, bringing back what was needed here. Only today she was a smuggler. The artificial and somewhat random lines drawn by a British lawyer had made her an outlaw. She was crossing boundaries. There were other boundaries to cross. The job a woman was allowed to do, the class signs on the coaches that she could not read but was constantly made aware of. The changing light and the smells as sheet (winter) went into boshonto (spring). The Ashar clouds that the photographers waited for, which seemed to wait until the light was right.

Rickshaw wallas find circuitous routes to take passengers across the VIP road. Their tenuous existence made more difficult by the fact that permits are difficult to get, and the bribes now higher. Hip hop music in trendy discos in Gulshan and Banani with unwritten but clearly defined dress codes make space for the yuppie elite of Dhaka. The Baul Mela in Kushtia draws a somewhat different crowd. Ecstasy and Ganja breaks down some barriers while music creates the bonding. Lalon talks of other boundaries, of body and soul, the bird and the cage.

Photography creates its own compartments. The photojournalist, the fine artist, the well paid celebrity, the bohemian dreamer, the purist, the pragmatist, the classical, the hypermodern, the uncropped image, the setup shot, the Gettys and the Driks. The majority world. The South. The North. The West. The developing world. Red filters, green filters, high pass filters, layers, masks, feathered edges. No photoshop, yes photoshop. Canonites, Nikonites, Leicaphytes, digital, analogue.

The digital divide. The haves, the have nots. Vegetarians, vegans, carnivores. Heterosexuals, metrosexuals, transsexuals, homosexuals. The straight, the kinky. The visionaries, the mercenaries, the crude the erudite, the pensive the flamboyant. Oil, gas, bombs, immigration officials. WTO, subsidies, sperm banks, kings, tyrants, presidents, prime ministers, revolutionaries, terrorists, anarchists, activists, pacifists, the weak, the meek, the strong, the bully. The good the evil. The hawks the doves. The evolutionists, the creationists. The crusaders the Jihadis. The raised fist, the clasped palms. The defiant, the oppressive, the green, the red. The virgin.

Whether cattle are well fed, or children go hungry, whether bombs are valid for defence, or tools of aggression, boundaries ? seen and unseen ? define our modes of conduct, our freedoms, our values, our very ability to recognise the presence of the boundaries that bind us.

Festival Website

Colliding with the State

![]()

Lisa Botos from the Time Magazine office in Hong Kong, had done most of the hard work. Permissions had been obtained and the protocol arrangements had been made. The shoot was on. Having gone through the security hoop at the prime minister?s secretariat, I had settled in at the waiting room along with my colleagues photographer Aminuzzaman from Drik and writer Alex Perry and William Green from Time. That was when the trouble started. Officials rushed to usher me out of my seat. I was wondering what other security alert I had triggered off. My faux pas was somewhat more embarrassing. I had been sitting on the prime minister?s chair.

I had only been allocated a few minutes for the cover shoot, which went well despite one of my lamps blowing on me, but luckily the prime minister had agreed to our suggestion that we follow her on her trip to Pabna. I scurried to change gear for the outdoor shoot. Emptying memory cards, handing over existing images to to take to the library, a quick visit to the loo, were all things that needed to get done, except that I was told ?hurry, she is on her way to the helicopter.? Dumping equipment into my camera bag, handing over my laptop to, I stuck my digital wallet into the pile and made a dash for it. The loo would have to wait. That was when a strong arm jutted out in the corridor. The security guard had prevented me from running into the prime minister! Alex calmly asked me if I had run into other heads of state before. ?Only once? I had said, as I had nearly bumped into Mahathir while running up the stairs at the Mandarin Oriental in Kuala Lumpur. But that was a long time ago.

It was a long and eventful day and one I must write about, but for the moment you?ll need to settle for the cover image of the current Time Magazine (10th April 2006 issue) and Alex?s writeup.

Having the Eye

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

| Preface to Drik Calendar 2006 | |

|

It was a stinker of a letter. Written to an organisation I knew little about. I was angered that World Press Photo (WPP) had little to do with the world and was largely about European and North American photography. Though it featured work from all over the globe, the jury, the photographers who entered the contest and the winners were largely white western males. So in my letter I had suggested that they rename themselves Western Press Photography. The phone call was a surprise. We didn’t get too many overseas calls in those days. The managing director of WPP Marloes Krijnen, politely pointed out that they too had written me a letter, still on its way, which was dated prior to my letter, and hence had not been written in response to my tirade. They had just asked me to be a member of the international jury. My letter had also mentioned that I considered WPP to be a very important contest despite its shortcomings, and should the opportunity arise, I would be interested in hosting the show in Bangladesh . This led to the second part of the conversation. While the exhibition is generally booked way in advance, there had been a cancellation, and should we want it, the show could be made available in three weeks. Having recovered from the initial excitement of being asked to be on the jury of what is considered the pinnacle of press photography, I tried to compose myself and considered the options. I needed time, and asked Marloes whether she could call back in a couple of hours. The exhibition could only be shown in its entirety, and we had faced considerable problems with our own exhibitions. The major galleries were either state-owned or belonged to foreign cultural centres not prepared to question the government, or be controversial in any way. Our work had always been critical of the government and the elite, the donor community, the patriarchal system and of the self appointed protectors of religious and family values. We didn’t know of a single gallery that would guarantee that no censorship would take place, except for our own gallery. There was just one small problem. Our gallery hadn’t yet been built. We had drawn up the architectural plans for it though, and part of the superstructure was in place, but still no gallery. I was stalling. Rafique Azam was then not the superstar that he is now. This was his first project, and we had wanted to give these young architects a free hand to interpret our ideas. I rang him up and asked him if he could build us a gallery in seventeen days! Rafique didn’t react as badly as one might have expected. He knew I was crazy enough to have meant it and having told me how ridiculous the idea was, settled down and gave me a list of all the things he would need to make it happen. He needed to work round the clock, a fair bit of money, some of it the following morning, and full freedom. There could be no slip ups in the supply chain. It was going to be a race to the finish as it was. Osman Chowdhury was a client, but it was as a friend that I rang him up. There was no way he could organise the sort of money we needed at such short notice from his company, but he was able to promise a sum that we could get started with. And he could provide it the next morning. Marloes rang as she had promised, and I said we would be happy to host the exhibition, in our own gallery. There the polite conversation ended. But that was also the beginning of a wonderful relationship between our two organisations, World Press Photo and Drik. A relationship that has blossomed over the years. It didn’t take long for the news to spread. Mr. Gajentaan, the Dutch ambassador was a friend who had a strong interest in the arts, and had arranged photo exhibitions in his home in the past. Excitedly he rang me and wanted to come straight over. WPP coming to Bangladesh was big news, and he wanted to be part of the action. He was calm enough when we told him about our plans to have it in three weeks and in our own gallery. It was when we told him he was standing inside the gallery that he flipped. There was no gallery. ?Do you realise this is the most prestigious photo exhibition in the world?? he asked. Yes, we knew. And we would have a good show. A much shaken ambassador went back to Gulshan. To be fair, he didn’t call World Press to tell them that the gallery was only being built. There was more to the story. It was 1993 and the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party were fighting each other in the streets, locked in a bitter battle for power. This we felt, could be a chance to unite these warring factions. We knew there was no chance of getting the two leaders of the parties at the same table, but the deputy leader of the BNP was Dr. Badruddoza Chowdhury, a student of my father, and we could probably approach Abdus Samad Azad through a personal friend Kaiser Chowdhury who was then the chief whip of the Awami League. Having been so critical of World Press Photo in my letter to them a week earlier, I was now extolling its virtues to two of the most powerful politicians in the country. Kaiser and my mum did the original groundwork, and I put in a good pitch about how this would demonstrate to the nation that they were forward looking political parties, and how much media coverage the event would have. It worked, and they agreed to jointly open the show. Now I had another tool to play with. While local media didn’t really know much about World Press, the fact that these two sworn enemies were going to open a show together was big news, and we managed to get the media excited. Mahfuz Anam of The Daily Star, the biggest English daily, agreed to do a whole media campaign around the event, and the bits were beginning to fall into place. At the packed press conference on the veranda of my parents’ home (Drik rents the upper floors), we were stalling for time, to let the paint dry in the gallery upstairs! ?rp?d Gerecsey the curator (who later went on to become managing director of WPP) and Bart Nieuwenhuijs, the board member who had come to setup the show, huddled with my colleagues and spoke in agitated whispers. Who was going to bell the cat? Eventually it was Bart who came up to me. They wanted to put in nails on the freshly painted walls! We did put in those nails, and the show was a spectacular success. The two deputy leaders cut the ribbon together, and confessed that they enjoyed sharing a cup of coffee, despite their political differences. The media went gaga. WPP and Drik had together pulled it off. Since then, the two organisations have continued to work together at many levels. An impromptu seminar for press photographers followed. We arranged for the show to go to Kathmandu and Kolkata. Rabeya Sarkar Rima of the Out of Focus group became the first Asian child jury member. I remember telling Marc Proust when he came to curate yet another WPP exhibition in our gallery, that Nurul Islam, the young man who sold us flowers in Monipuri Para, had also been a former child jury member. We had the WPP retrospective exhibition at the National Museum at the first Chobi Mela, the festival of photography that we launched. We collaborated on many other things. We started nominating young Asian photographers for the Masterclass, and one year, two photographers from Pathshala, our school of photography, GMB Akash from Bangladesh and Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi from Zimbabwe were amongst the twelve talented photographers in this international pool. Pathshala itself relied heavily on WPP for its existence. With no state or other external funding, it was always going to be difficult to setup and maintain a school of photography in our region. We utilised the first WPP seminar programme to launch the school, and the tutors and the workshops that WPP provided became important anchors for what has now become a degree programme. WPP even provided a grant which was a big help in those early days. Since then we have collaborated on training Asian and African photographers in regional programmes organised in Jakarta and Kenya , and been involved in longer term educational projects in Sri Lanka and Tanzania . I myself worked in the jury another three times, once as chair, and I have spoken at several WPP events. Interestingly, it was the very issues I had raised in that original letter which the two organisations have worked together to try and solve, and both WPP and Drik are very different organisations today. It is to celebrate that friendship, on the 50th Anniversary of World Press Photo, that we put together this calendar. The images are by the majority world participants of WPP seminars and their tutors, some of the finest photographers around. It is a protest against the continued use of exclusively white western male photographers to document the majority world that developmental agencies and western media have made their standard practice. It is a direct answer to the superior race argument that they continue to use to justify their actions and to dismiss our work when they say ?they don’t have the eye?. Shahidul Alam |

|

Where Elbows Do The Talking

![]()

It was a mixed week. Sandwiched in between the hartals and the ekushey

barefoot walks and the launch disaster, were news items that led to very

different emotions at Drik. Shoeb Faruquee, the photographer from Chittagong, won the 2nd prize in the Contemporary Issues, Singles,

category of the world’s premier photojournalism contest World Press

Photo. The photograph of the mental patient locked by the legs as in a

medieval stock, is a haunting image that is sure to shake the viewer.

However, the stark black and white image tells a story that is far from

black and white. In a nation with limited resources, medical care for

all is far from reality. Expensive western treatment is beyond the reach

of most, and has often been shown to be flawed. Alternative forms of

treatment is the choice of many. The fact that the boy photographed was

said to have been healed, further complicates the reading of this image.

Shoeb is one of many majority world photographers who have attempted to

understand the complexities of their cultures, which rarely offer

simplistic readings.

It was later in the week, that Azizur Rahim Peu, told me that the

affable contributor to Drik, Mufty Munir, had died after a short illness

at the Holy Family Hospital. I would contact Mufty when I was in

trouble, needing to send pictures to Time, Newsweek or some other

publication. We would work into the night at the AFP bureau, utilising

the time difference, to ensure the pictures made it to the picture desk

in the morning. Occasionally, while hanging out at the Press Club

waiting for breaking news, we would dash off together. Mufty

uncomfortably perched on the back of my bicycle and me puffing away

trying to get to the scene in time.

Wire photography is about speed, and their photographers are known for

being pushy, but this shy, quiet, self effacing photographer made his

way to the top through the quality of his images. We had to push him to

have his first show in 1995, which our photography coordinator Gilles

Saussier and I curated. The show at the Alliance was a huge success, but

Mufty was not impressed by the excitement the show had created. He

simply wanted to get on with his work.

He did have problems with authority, or rather, authority had problems

with him. Despite his shyness, he was a straight talking photographer,

who didn’t hesitate to protest when things weren’t right. Not being the

subservient minion the gatekeepers of our media are accustomed to, he

often got into trouble. But the clarity of his protests played an

important role in establishing photographers’ rights. In the abrasive

world of press photography, where elbows do much of the talking, this

gentle talented practitioner will be dearly missed.

Unknown to the rest of us, the brother of Rob, the gardener at Drik,

died in the launch that sank in the storm at the weekend.