Kalpana Chakma’s unresolved abduction 20 years on…

Photographs and interviews by Saydia Gulrukh

Kalindikumar Chakma (Kalicharan)

Kalpana?s eldest brother

?The hill people do not get justice, look at Yasmin, some justice was done, but people of the hills don?t get any justice. It?s been twelve years…The VDP [Village Defence Party] member Nurul Huq, and Saleh came with Lieutenant Ferdous to this house that night. They still strut around. They live in the neighbouring Bengali village. Go there. You will find them. I have told the BDR [Bangladesh Defence Rifles] commanding officer, you say you can?t find him, well, his accomplices are around, why don?t you question them?

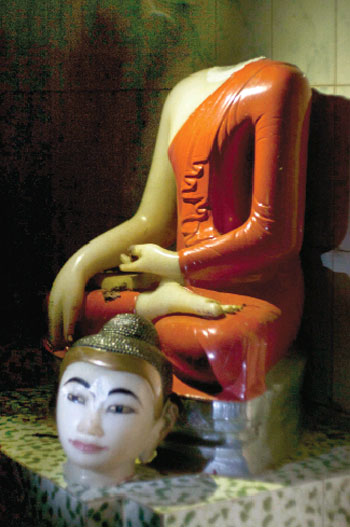

Kalpana?s clothes kept in her brother Kalicharan?s home

?She had a black bag, she took it to Dhaka. I have kept all her things in it. All these years. But the mice have been at it. She had many books… I educated her up to I.Com, I got her admitted to the degree classes, I thought our lives would become a bit better, but no, they came and took her away… I do not know to this day whether she is dead or alive… They should at least tell me that she has died so that we can give dharma, do what religion asks of us. People of all religions have a right to do what should be done.?

Mithun Chakma

Kalpana Chakma?s comrade

?I was picked up by the army when I was delivering a speech at a PCP rally, on the 6th of August 2004. They took me to Khagrachari camp, blindfolded me, took me to a room, asked me to lie down [on a bench], put up my legs, then they began beating me on the soles of my feet with the butt of a hockey stick. They beat me for a long, long time, they said things like, ?What is your name? What do you do?… [Why do] you take up arms? What are your ideals?? Lots of other things, ?You do not know that we ? the army ? have learnt how to torture, we have had training from the US.? They also said other things, ?And the Kalpana thing, well we did that, but nothing happened, right???

The well in New Lallyaghona village, in front of Kalpana?s house

?They brought Kalpana and her two brothers to this well, and blindfolded them… I think they pushed them over to that beel [marshes]. They got her to enter the waters, and then shot her… [The next day] villagers scoured the waters all day long with fishing nets. But her dead body was not found.?

by Meghna Guhathakurta

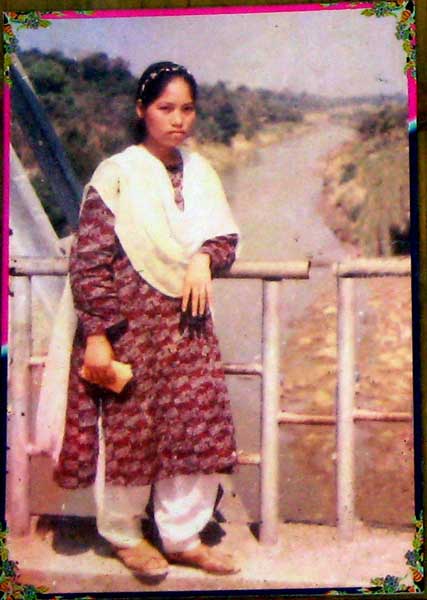

Kalpana, a first year graduate student of Baghaichari College, was a conscious, vocal and hardworking activist who fulfilled her role as organising secretary of the Hill Women?s Federation with commitment and resolve. Systematic and pervasive military presence in the hill tracts has made Pahari women more conscious of their rights. This is vividly borne out by what Kalpana writes in her diary, recovered by journalists from her home after her disappearance. Parts of this diary were serially published in the Bengali daily Bhorer Kagoj. Later, it was reprinted along with other writings in an anthology, Kalpana Chakma?s Diary, published by the Hill Women?s Federation (2001).

Kalpana introduces her ?daily notebook? through the following lines: ?Life means struggle and here are some important notes of a life full of struggle.? In depicting the life of a woman in the CHT, she writes, ?On the one hand, women face the steam roller of rape, torture, sexual harassment, humiliation and conditions of helplessness inflicted by the military and Bengalis. On the other, they face the curse of social and sexual discrimination and a restricted lifestyle.? However, Kalpana?s understanding of oppression embraces all women of Bangladesh, ethnic and Bengali. She writes elsewhere: ?I think that the women of my country are the most oppressed.? In expressing her yearnings for freedom from oppression she uses a beautiful metaphor: ?When a caged bird wants to be free, does it mean that she wants freedom for herself alone? Does it also mean that one must necessarily imprison those who are already free? I think it is natural to expect the caged bird to be angry at those who imprisoned her. But if she understands that she has been imprisoned and that the cage is not her rightful place, then she has every right to claim the freedom of the skies!?

Kalpana?s reading of the woman question is a feminist one. Her feminism allows her to look at the woman question in terms of Bengali domination, as well as in terms of sexual politics within her own community. This is striking and unique since in most nationalist or ethnic movements the gender question becomes a subtext to the larger ?national? one. Kalpana?s feminism differs sharply from that of her middle-class Bengali sisters. Her struggle, unlike theirs, pitches her to confront military and racial domination in a manner incomprehensible to most privileged Bengalis. ***

Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics

Brill Academic Publishers, 2005

By Suad Joseph and Afsaneh Najmabadi

IN THE late 1980s conflicts of state versus community were sharply on the rise. In Bangladesh problems over the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) from 1980 led to a series of massacres, plunders and destruction of villages… [this conflict] had historical roots [it] became particularly violent in the 1980s and 1990s…in all these movements women played an important role in conflict resolution.

People in the CHT were antagonistic toward the government of Bangladesh from the time the Kaptai dam was built (1957-62) and thousands of people became homeless. In the early 1970s the whole of CHT was brought under military control. The original inhabitants of the CHT were the Jumma (tribal) people. They were aggrieved not just because of the dam but also because the state had undertaken to change the demographic balance of the region through a policy of settling Bengali Muslim people from the plains in the CHT. The protest of Jumma people brought forth severe counter-insurgency measures leading to extra-judicial killings and massacres by the state. The rebels also formed a military unit called the Shanti Bahini. In all of this the tribal women were targeted; this was dramatically brought to the fore by the abduction of Kalpana Chakma in 1996. While the region was being torn apart the Hill Women?s Federation (HWF), a secular women?s organization was formed in 1989 by women students of the Chittagong University. By 1991 it had become extremely popular…The main aims of these groups were justice for the tribal people of CHT and an end to violence. They were among the strongest voices for peace.

by Mithun Chakma

ON THE night of 11 June, 1996… Barely 7/8 hours [later] voting for the seventh National Parliamentary Elections [begin]…at about 1:30am..Mrs. Bandhuni Chakma, Kalpana?s widowed mother got out of bed and opened the door, her whole body was trembling in fear. They came out one by one: Kalpana, her two brothers, Khudiram and Kalicharan, the latter?s wife. The house was surrounded… A soldier flashed a torch on their faces, and Kalicharan recognised Lieutenant Ferdous, who had visited their house a few days back, and two VDP members ? Nurul Haque and Salah Ahmed. Amnesty International in an Urgent Action issued on 1st July 1996 wrote: ?Six or seven security personnel in plainclothes, believed to be from Ugalchari army camp (actually Lieutenant Ferdous was commander of Kojoichari Army camp), are reported to have entered the home of Kalpana Chakma in New Lallyaghona village, Rangamati district in the early hours of 12 June. Kalpana Chakma and two of her brothers were forcibly taken from their home, blindfolded and with their hands tied.?

What happened? The Ain-o-Salish Kendra report [says], They (army) took Khudiram near a lake and told him to step into the lake. As soon as he went in, the order to fire was given. Frightened, Khudiram took shelter in the water. He swam around for some minutes, then rose up and took shelter in a neighbour?s house, he had no clothes on his body. In the meanwhile, armed personnel blindfolded Kalpana and her brother Kalicharan. He heard the firing, ran and managed to escape. While running to save his life he heard two shots being fired, and heard Kalpana screaming. Kalicharan said, ?They shot at me and when I ran I could hear Kalpana crying out Dah Dah Mare Baja (Brother, brother save me!)…?

A cover-up attempt was made from the very beginning. Initially, the army termed it a ?love affair? [between Lieutenant Ferdous and Kalpana Chakma]. However, they backtracked later, and flatly denied their involvement in the abduction. When the issue refused to die down, they launched a vicious disinformation campaign. The Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission in its report Life is Not Ours (update 3) said, an NGO named Bangladesh Human Rights Commission declared at a press conference on 15th August 1996: Kalpana Chakma had been seen in Tripura (India), she herself had plotted her own abduction. Kalpana Chakma?s mother rejected BHRC?s statement and termed it a ?blatant lie?.

After months of protest and mounting international condemnation, the government constituted a three-member inquiry committee on 7 September 1996, headed by Justice Abdul Jalil. The other members were Sawkat Hossain, Deputy Commissioner of Chittagong and Dr. Anupam Sen, professor of Chittagong University. The committee is reported to have submitted its findings to the Ministry of Home Affairs a couple of years ago, but the government has still not made it public.

Meanwhile, a storm of protests swept the CHT. A general strike was observed in Marishya, the area to which Kalpana belonged. While the Jummas wholeheartedly supported the programme, some Bengali settlers attacked a rally, and shot dead 16-year old Rupon Chakma. The settlers also hacked to death Sukesh Chakma, Monotosh Chakma and Samar Chakma, on their way to Baghaichari bazaar to take part in picketing.

Lieutenant Ferdous, [allegedly] the mastermind behind the kidnapping, is reported to have been promoted to the rank of Major and posted back to Karengatoli army camp, not far from New Lallyaghona, Kalpana Chakma?s village.

Mithun Chakma is general secretary, Democratic Youth Forum. Edited excerpts from http: //jummonet.blogspot.com/2007/06/11th-year-of-kalpana-chakma-abduction.html

Sonali Chakma

President

Hill Women?s Federation

Kalpana Chakma will always remain a symbol of resistance in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The army?s attempt to silence Jumma women by kidnapping Kalpana in the dead of night has failed and will always fail. She will continue to inspire generations of women activists in the country.

It is regrettable that the inquiry report has not been made public after twelve years of her disappearance. We demand that the report be published without further delay and Lieutenant Ferdous, the [alleged] mastermind, and his accomplices be punished.

Sultana Kamal

Former adviser, caretaker government

Executive Director

Ain O Salish Kendra

Nearly twelve years ago we lost Kalpana Chakma, a person, a co-worker and a human rights activist. Her absence hurts us immeasurably. It evokes feelings of losing a friend, but not only that, it also raises questions about our nation?s conscience. Many of us have tried our best, we have made repeated appeals to the state, but to no avail. We have no reason to believe that effective steps have been taken.

If Kalpana is still alive, we would like her to know that we still remember her, that we look forward to her return. If she is not, if our worst fears are true, that she was murdered after being abducted, we want to stress that if we fail to realise her dreams, we fail to live up to our convictions.

Khaleda Khatoon

Human rights activist

Long live Kalpana, you have given voice to the protests of Pahari women. We need you. We need more women like you. We need leaders like you.

I want to raise two issues: first, a case was registered against Lieutenant Ferdous. Why is that not being revived, does the current government not have any responsibilities in this regard? I say this especially since Devashish Ray as special assistant to the chief adviser is now part and parcel of the government.

Second, the Kalpana Chakma abduction committee report has not yet been released. Since the caretaker government is considering a Right to Information Act, I would like to propose that they begin their journey by making this report public.

Moshrefa Mishu

Convener

Garments Sramik Oikya Forum

On the twelfth anniversary of Kalpana Chakma?s abduction, I demand that the incident be investigated urgently, without any prejudice or fear, so that we can learn what really happened, and that her family be provided security.

I also demand that the army be withdrawn from the Chittagong Hill Tracts and that the hill region be made autonomous. The person(s) who abducted Kalpana must be tried. We must keep Kalpana?s memory alive, and demand that justice be done. We must pay respect to her through re-creating her struggles.

I salute you Kalpana Chakma.

Anu Mohammed

Professor

Department of Economics

Jahangirnagar University

Kalpana Chakma?s abduction urges us to look again at the nature of the Bangladesh state. Kalpana belongs to a group of people fighting against ethnic domination, a group struggling hard to be rid of the army?s suffocating grasp. She has been missing for the last twelve years. An investigation committee was formed but all those accused were successfully hidden from public view. Inequalities, oppression, discrimination continue to exist in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and so does the struggle.

Kalpana Chakma is a symbol of protest and resistance. She will remain so forever.

Maheen Sultan

Member

Naripokkho

The struggle of the indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts for the protection of their lands, identity and cultural heritage is an ongoing one. Of the many violations suffered, the disappearance of Kalpana Chakma is one that drew attention of the human rights and women?s rights movement in Bangladesh. Twelve years on, her disappearance is still a puzzle. Demands for an official enquiry, like all other national enquiries, resulted in nothing. It is ironic that while much lip service is paid to good governance and transparency, the public has never been presented with the findings of the enquiry. The lack of transparency is particularly acute in the case of the defence forces. Just as ordinary citizens are in the dark about the defence budget and expenditures, so are we in the dark about the militarisation of the CHT, and whether any actions have been taken against the innumerable wrongs committed against our own peoples, simply because they are not Bengali.

We demand that the present government make the enquiry report public, so that justice can be done.

New Lallyaghona

1/4/96

Shaikat Da,

Greetings. I got your letter yesterday. We are in good health. But I feel unsure. Something terrible might happen any moment. I am very worried.

News from here ? on 28.2.96 a miscreant called Ishak was taken away. Since then the Bengalis have been wanting to attack the Paharis. In this agitated situation, the third annual conference of Pahari Chhatra Parishad?s branch was successfully held on 7.3.96 (according to its earlier schedule). A nineteen-member Thana Committee has been formed with Purba Ranjan as the President, Dharanimoy, its Secretary, and Prabir, its Organising Secretary. The Baghaicchori branch held a cultural programme for the first time, where the 1988 play Norok was staged.

And [news from] there, Bengali agitation has increased since 11.3.96. They have been holding meetings and processions. Paharis have become fearful, ?ready to flee? at any moment. But I was not here. I had gone to Barkal on organisational work. I returned on the 13th and heard the details. Bengalis have forbidden Paharis from entering the bajar area or Bengali neighbourhoods, they have even forbidden Paharis to talk to Bengalis. After this, the work of uniting Paharis began. In other words, resisting attacks in the whole Kassalong area. Guarding at night has begun. On the other hand, Lieutenant Ferdous, the army camp commander of our village, has made false promises to village elders, and held meetings with them. Many other incidents, small in nature, have kept occurring. Especially, since the Bengalis have targetted four of our neighbouring villages including Battala.

In this situation, on the 19th of March, cries were heard all over Kassalong, and that infamous Lieutenant Ferdous came to our New Lallyaghona village and burnt down 9 homes that belonged to 7 families. They beat up the Pahari nightguards most severely. After this, the DC, SP and Communications Committee (JSS) Secretary Mathura Lal Chakma had meetings which calmed the situation somewhat. They were told that if Ishak was not released by the 5th [of April], Bengalis were likely to muddy the waters further. The DC and SP are unable to bring the situation under control. At present, people are fearful of what might happen after the 5th. We are leading uncertain lives.

It is Bengalis who are behind this agitation and this time we have been able to teach them a lesson. Usually, Paharis flee from their villages but now they go to those very places from where you can hear cries. Bengalis, indisciplined as they are, have been taken aback at this unity and are afraid, along with the others. The administration has also witnessed this unity.

The present situation: Baghaicchori is isolated from all other parts. Chakma telephone lines have been cut, Paharis are not given access to other lines. We are not allowed to go to the marketplace. Maybe there will be no postal communication until the situation calms down. Maybe there will be no letters even.

That?s all for now. Lastly, I send you advanced Boishabi greetings.

Yours

KC

PS: I wrote this letter hurriedly. If my sentences are awkward, please correct them.

Shaikat Dewan is a member of Pahari Chhatra Parishad. Source: Kalpana Chakmar Diary, Dhaka: Hill Women?s Federation, 2001, pp. 69-70.

1993-1996

1993? Kalpana?s political life began as women?s secretary of Baghaichari Pahari Chhatra Parishad.

March 1993? took on responsibilities of the convening committee, Hill Women?s Federation, Marishya branch.

January 15, 1995? took part in the first central conference of the Hill Women?s Federation, Khagrachari.

May 21, 1995? Kalpana is elected organising secretary of the central committee at the HWF conference, held in Khagrachari.

November 17, 1995? meeting of three Pahari organisations held in Naniarchar Khedarmara High School premises to express grief and outrage at Naniarchar killings in Rangamati. Kalpana addresses the meeting.

February 28, 1996? Ishak, a Bengali, is abducted from New Lallyaghona village. Tension increases between Paharis and Bengalis.

March 19, 1996? Nine houses belonging to seven Chakma families of New Lallyaghona village burnt down. Kalpana protests against the arson attack.

April 1996? Lieutenant Ferdous goes to Kalpana?s house a few days before Baishabi (New Year festivals). He is accompanied by 20-25 soldiers. Heated exchange between Kalpana and Lieutenant Ferdous.

April 12, 1996? meeting of three Pahari organisations held at the Rangamati Shilpakala Academy on the occasion of Baishabi. Kalpana appeals for unity.

June 12, 1996? at 1:30am Lieutenant Ferdous and 7-8 others in plainclothes enter Kalpana?s house, they order her, and her brothers Khudiram and Kalicharan, to go with them.

This chronology has been constructed from letters, news reports, and `Investigating the Kidnapping of Kalpana Chakma?, Ain O Salish Kendra Report, published in Kalpana Chakmar Diary (Diary of Kalpana Chakma), Dhaka: Hill Women?s Federation, 2001

First published on New Age 12th June 2008