Category: Military

9/11, Mossad, and a super 9-11 in the offing

By Rahnuma Ahmed

Anti-Semite, Jew hater, Holocaust denier are the epithets one is bound to gather if one voices criticism of Israel. Of Zionism.

Historian Tony Judt, of Jewish background himself, had written on Israel’s 58th birthday, Israel is like an adolescent. It is convinced that it can do as it wishes. That it is immortal. That no one understands it. Everyone is against it. It is unique (`The country that wouldn’t grow up,’ Haaretz, May 2, 2006).

And after all, as God’s “chosen people” how can they be blamed? Self-deluded into thinking that they are distinct?especially from their Arab neighbours who are barbaric, fanatics, dirty, smelly?imagine their shock when a research aimed at studying genetic variations in immune system genes among Middle Eastern people discovered otherwise, that Jewish people are genetically not distinct from their neighbors. What was to happen now to the Jewish claim that they are special? That Judaism can only be inherited? (`Mideast Jews, Palestinians Virtually Genetically Identical,’ The Observer, November 25, 2001).

And how did the scientific community react? Did members scratch their heads and say, Oh good, now the Israelis will realise that it was all a big mistake. They’ve been slaughtering and grabbing land from people who’re actually their brothers… All this horror can stop. We can have peace. Finally!

No. The paper was pulled from Human Immunology, the American journal in which it’d just been published. It was removed from the journal’s website. Academics who had already received journal copies were urged to rip out the offending pages. Libraries and universities throughout the world were asked to either ignore it or “preferably to physically remove the pages.” The author, Spanish geneticist professor Antonio Arnaiz-Villena was sacked from the journal’s editorial board.

If Arnaiz-Villena had found evidence that instead of being “ordinary,” Jewish people were genetically “very special,” wrote a fellow scientist, “you can be sure no one would have objected.”

Israel, as we can all see, has refused to grow up. If it had, it would have, at the very least, done what Judt had advised 4 years earlier: dismantle the major settlements. Open unconditional negotiation with Palestinians. Offer Hamas leaders something serious in return for recognition of Israel and a cease-fire.

It would have realised that it cannot count indefinitely upon the unquestioning support of the United States. That the worldwide scrutiny of its everyday behaviour towards the Palestinians, only a TV button or a mouse click away?curfews, checkpoints, bulldozers, home destructions, land grabbings and settlements, slaughter in Gaza dubbed the world’s largest open-air prison, apartheid wall, targeted assassinations, theft of western passports?would eventually lead to a situation where, as Judt puts it, “the fact that the great-grandmother of an Israeli soldier died in Treblinka,” or Auschwitz, is no excuse for his own abusive treatment of a Palestinian woman waiting to cross a checkpoint. That it would lead to a situation where Israel would no longer be able to cash in on the Holocaust.

It will be most unfortunate. Zionism will provide the excuse for the rise of genuine anti-Semitism, for exacting the price?from both Zionist, and non-Zionist Jews?for not having learnt lessons from history.

Judt had issued a warning: “something is changing in the United States.” Ten years ago, he said, John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt’s The Israel Lobby would possibly not have been published. Not even from London. A sea-change is taking place. It is leading prominent thinkers, including erstwhile neo-conservative interventionists like Francis Fukuyama to hard-nosed realists like Mearsheimer and Walt (“prominent senior academics of impeccable conservative credentials”) to voice the concern that Israel is “a liability.” If America is to regain her “foreign image and influence” the umbilical cord which ties US foreign policy to the needs and interests of Israel must be severed.

US military circles apparently are not far removed from these changing concerns. As Dr Alan Sabrosky, former director of studies of the American War College said in a recent interview, his article, in which he alleges that 9/11 was a Mossad-CIA operation, is being read by people in the Headquarters Marine Corps, the Army War College. At first it is met with disbelief. But once people get convinced, they get angry. Very angry, he said. That’s because the military, unlike the Congress, the White House, and the media, has not been bought (see last week’s column, The `Mad Dog’ in the Middle East).

It is a conviction that seems to be shared by Gordon Duff, a Marine Vietnam veteran, and a widely published expert on military and defense issues. Israel’s powerful group around Bush ?the PNAC-ers, the neo-cons?is not present in the current administration, but the idea, as Duff explains, had been that regardless of who was voted to power, whether it was John McCain or Barack Obama, Rahm Emanuel would be there, “to pull his strings” ?(Emanuel is the White House chief of staff at present). And they still have the Clintons, both Bill and Hillary, the State department, and “AIPAC’s ability to put 75% of the members of congress around anything from a resolution that the moon is made of green cheese to `National Have Sex With Your Child Day.’ Equally importantly, the media giants controlled by Israeli assets and Christian Zionist allies are in position in Germany, the UK and the US, and along with Canada, Australia and New Zealand, these assets are quick in “suppressing news, running any story and manipulating the masses.”

Things started to go wrong for Israel, writes Duff, when top military leaders increasingly became suspicious of 9/11 (April 24, 2010). Of the possibility that Israel was involved in 9/11. It is a suspicion which has festered like an open wound. General Petraeus, the senior operational commander, the person really in charge of the US military, has told Admiral Mullen that Israel is not subjected to any foreign threat. That it has become “a massive liability.” Obama, writes Duff, was confronted with a choice. He was told that neither the military nor the intelligence services are prepared to participate in attacks on Iran “under any imaginable circumstances.” That, if the US wanted to attack Iran, “he and Emanuel Rahm would have to invade Iran personally” (and I cannot help think who’d blame them with 18 attempted suicides per day among American war vets?).

As Israel lined up its collaborators in the US, Obama went after “Israel’s biggest prize in America, Goldman Sachs,” its prime asset for controlling America. For looting America. According to Duff, the alliance between the US and Israel has totally broken down. The most liberal and the most conservative members of congress have signed up in support of Goldman Sachs, and lined up against the President and Pentagon, who are are aligned together. In support of his argument, he asks: why [else would] extreme liberals and conservatives all attacking President Obama and, less visibly, our military leaders, all at the same time? Who is orchestrating this oddest turn of political events in recent history?

And in this oddest of situation backroom chatter has increased: a terror attack is imminent. Iran will be blamed for it. The primary suspect is Israel since “only a new 9/11 can bail Israel out,” writes Duff. According to rumors, the weapons are in place in Europe and the US. Arabs, Iranians, Pakistanis, some kind of Islamic terrorist group, have already been recruited. Or invented. News stories have already been drafted (I’d like to remind skeptics of 9/11, when BBC news correspondent Jane Standley had reported the collapse of Building 7, a good 23 minutes before the actual collapse time). Film crews are on alert. Witnesses will be briefed, they will say, Yes, it was an Arab dirty bomb. We saw them. Middle Eastern-looking. They must have bought the bomb from North Korea. After the story has hit the news, these stunned survivors will suddenly disappear. We all know where.

A super 9-11. But will this one, now that suspicions have been raised, now that Israel’s cover has been blown, will it generate `super’ sympathy for Middle East’s `mad dog’?

May be not. Once bitten, twice shy.

Published in New Age

The `Mad Dog' in the Middle East

By Rahnuma Ahmed

![]()

What Dr Alan Sabrosky has done is bell the cat. Except that it’s a dog, and not a cat.One that’s utterly mad. Insane.

In the words of late General Moshe Dayan, who went on to become Israel’s defense minister, and later foreign minister, Israel’s security depended on its being viewed by others as a mad dog.

Dr Sabrosky, who has been calling for a new investigation on 9/11 for some time, said in a recent radio interview (March 19), it would have been impossible to stage 9/11 without the full resources of both the CIA and Mossad. Nine-eleven, he said, served the interests of both the agencies. “They did 9/11. They did it.”

“..it is 100% certain that 9/11 was a Mossad operation. Period.” (Full transcript). Now if Dr Sabrosky had been let’s say, a Pakistani, or worse still, an Iranian, one could have pooh-poohed. A loony, like all mollahs are. If he’d been Muslim, one could have labelled him an anti-Semite. After all, the Iranian president denied the holocaust. That’s what the western media said and they’d never lie, would they? Crazy dictator with nuclear weapons. Will deny being from his mother’s womb next. Pathetic.

But unfortunately Alan Sabrosky (Ph.D, university of Michigan) is a ten year US Marine Corps veteran. A Vietnam war vet. An American of Jewish ancestry. He’s not only a graduate of the US Army War College, he was director of studies there. For five and a half years. Now if he says he’s convinced the Israelis did it… it’s to say the least, pretty difficult to ignore. Although the mainstream western media, the beacons of the free world, are doing their darndest best. Do a google search on Dr Sabrosky plus any of these beacons New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian… BBC, CNN websites, your search will come to nought. It’s only in the alternative press. A few blogs. Pravda online. Less than a handful of 9-11 truth websites (no, not all, interesting, eh?). It’s only in these places that you’ll come across links to his interview. And his recent article, `The dark face of Jewish nationalism’ (March 12, 2010).

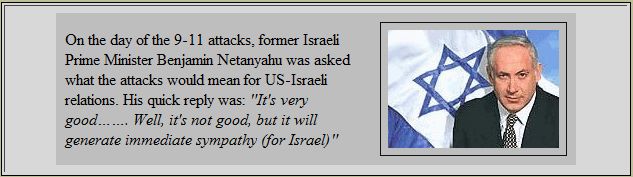

Jewish nationalism is unique, he writes. Prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu had said at a Likud gathering “Israel is not like other countries.” For once, he was speaking the truth. What makes its nationalism distinct to that of other countries?all the rest have both positive and negative aspects, both unifying and extremist features?Jewish nationalism is extremist per se. Among both secular and practising Jews. It is a real witches brew of xenophobia, racism, ultra-nationalism and militarism, a mixture that cannot be contained within a `mere’ nationalist context. Its `others’ have to be pushed out. Either into camps, or out of the country. Second, Zionism undermines civic loyalty among its adherents in other countries. Loyalty to Israel supersedes the loyalty to the country to which one belongs. Whether US or UK, or any other. For instance, Rahm Emanuel. He’s the White House chief of staff. The second most powerful person in the US. He served in the Israeli army but not in the US armed forces. Once independence is achieved, and this is the third feature of Jewish nationalism, it’s not unusual to have normal relations with the former occupying power. But no, not in the case of Israel. It has a long list of enemies. They have become America’s enemies too. Lastly, nationalist movements usually don’t displace the indigenous population wholesale, instead, they incorporate. They accommodate. The Americans are an exception, look what they did to the Indians/native Americans. Maybe that’s why most of them don’t care about what the Israelis are doing to the Palestinians.

In his radio interview with Mark Glenn and Phil Tourney (USS Liberty survivor), Sabrosky explains, most Americans don’t care much about what happened to the USS Liberty. For those who don’t know, I add, Israel attacked the US Naval ship USS Liberty in 1967 during the Six Day war. It was a false flag operation (like 9-11), the plan was to blame the attack on Egypt, to drag the US into the war. President Johnson seems to have known about it in advance; 34 Americans were murdered, 173 were wounded. Sabrosky says, That’s history. But 9-11 isn’t.

It has led directly to 60,000 Americans dead and wounded. In other countries, “hundreds of thousands of people.” Killed, wounded, made homeless. Tourney is sore about the Liberty, while Sabrosky himself is sore about Vietnam. But Americans are sore about 9-11 which is an “open wound.” He says, If Americans ever know that Israel did this, they’re gonna scrub them off the Earth, and they’re not gonna give a rat’s ass?forgive my language?what the cost is. They are not going to care. They will do it. And they should.

When Glenn asks Dr Sabrosky what is the reaction in US army circles (his work is being read by people in the Headquarters Marine Corps and at the Army War College) to his conviction that 9-11 was a Mossad operation, he answers, at first, astonishment. Disbelief. He does not get into arguments, he says. Who was flying what, who was where, whether there was nano-thermite (high-tech energetic materials prepared under military contracts in the USA, part of secret military research) or not, “those things are true, but they’re incidental.” What is necessary is to tell people that three buildings went down, the third was not hit by a plane. He then shows them an interview with a Danish demolitions expert, Danny Jowenko. It shows WTC7 going down. I tell them, “Now you understand that if one of the buildings was wired for demolition, all of them were wired for demolition.” And that, says Sabrosky, is the tipping point. At that point, people get angry. Really angry. And they say, “They did it, didn’t they.” He replies, “Yep?they did it.

” While asking Dr Sabrosky what he thinks is going to happen, Glenn says he himself thinks that Israel is going to pull off another 9-11, “sooner than any of us realize or would like to envision.” That powerful people think so too, such as the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Mike Mullen who cut short a trip to Europe several years ago (July 2008), quickly flew to Israel, to warn them that there should not be “another USS Liberty part two.” That a part two would already have occurred if increasing numbers of people had not been talking about 9-11. He adds, “I think that Israel has been watching all of this and has been saying, “We need to kind of let things cool a little bit for now?if we try to pull another one off right now then that’s it: we’re going to blow our cover.”

Sabrosky butts in saying, If Americans ever truly understand that they’ve been had, Israel will be history. “It’ll be a bloody, brutal war.” Israeli leverage, he explains, is confined to political appointments?to the Congress, to the White House. And to the media (“the mainstream media have paid more attention to Sarah Palin’s wardrobe than they have to dissecting blatant falsehoods”). But “the military has not been bought.” It is loyal. If it ever really, really deeply understands this, that they did 9-11, that the US government could in any way be involved in high crimes and treason against the people of the United States, “Israel’s going to disappear. Israel will flat-ass disappear from this Earth.”

And what does he think is going to happen soon? “We’re going to have a war with Iran.” The Arab street is going to explode. There are American forces, American units, like the 5th fleet headquarters in Bahrain, there’s going to be a long casualty list. If the Iraqi resistance had not been so strong, the attack on Iran, which was the “big prize” all along, would have happened in the second Bush administration. The pattern, he’s convinced, was: Afghanistan in 2001, Iraq 2003, Iran 2005, Syria 2007. The time frame now is a bit different, and although he’s not sure as to how it’s playing out, they are trying to “create an excuse for a war.”

I myself find it interesting that the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad recently wrote a letter to Ban Ki-Moon, the UN Secretary General (April 13, 2010) urging him to appoint an independent fact-finding team, a trustworthy one, to launch a comprehensive investigation into the “main culprits” behind the September 11 attacks since that is the “principal excuse” for attacking the Middle East. For NATO’s military presence in Afghanistan and Iraq. For making policies and launching military actions on the “pretext of fighting terrorism.

” Israel is a “monster,” Dr Sabrosky has written elsewhere (`I Express My Jewish Identity in Cuisine, Not in Foreign Policy’ July 9, 2009). And although more and more American Jews are speaking out, it might be too little too late. “Excising this ultra-Zionist/neo-con cancer is not going to be easy.” Maybe what needs to be done, an option that general Dayan had neglected to note, is to “kill that mad dog before it can decide to go berserk and bite.”

Extreme nationalism begging extreme solutions.

Published in New Age, April 26, 2010

![]()

Ghosts

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

By Ian Buruma

Volume 55, Number 11 ? June 26, 2008

The New York Review of Books

Two photographs, taken by digital camera at Abu Ghraib prison, on the night of November 5, 2003. The first picture shows a person in a ragged black poncho-like garment standing precariously on a tiny box. Hairy legs and arms suggest that this person is a man. His head is covered in a pointed black hood, his arms are spread, and his fingertips are attached to wires sticking from the concrete wall behind him. The pose hints at a crucifixion, but the black poncho and hood also suggest a witch or a scarecrow.

The second picture shows a young woman hunched over the corpse of a man. The corpse lies in a half-unzipped black body bag filled with ice cubes wrapped in plastic. His mouth is open; white bandages cover his eyes. The young woman grins widely at the camera. She holds up the thumb of her right hand, encased in a turquoise latex glove.

The photographs look amateurish, a crude mixture of the sinister and lighthearted. When they were published, first in The New Yorker magazine, we were provided with some background to them, but not much. The anonymous man in the first picture had been told that he would die of electric shock if he fell off the box. Hence the wires, which were in fact harmless. Information about the second picture was sketchy, but the woman seemed to be gloating over the man’s death. The bandages suggested serious violence. There were other Abu Ghraib photographs, published widely on the Internet: of terrified Iraqi prisoners, stripped of all their clothes, being assaulted and bitten by dogs (“doggie dancing”); of a naked prisoner on all fours held on a leash by a female American guard; of naked men piled up in a human pyramid; of naked men made to masturbate, or posed as though performing oral sex; of naked men wearing women’s panties on their heads, handcuffed to the bars of their cells; of naked men used as punching bags; and so on.

The photographs evoked an atmosphere of giddy brutality. The reputation of the United States, already tarnished by a bungled war, hit a new low. But interpretations of the photographs, exactly what they told us, varied according to the observer. After he was criticized for failing to apologize, President Bush said in a public statement that he was “sorry for the humiliation suffered by the Iraqi prisoners, and the humiliation suffered by their families.” But he felt “equally sorry,” he said, “that people who have been seeing those pictures didn’t understand the true nature and heart of America.” Donald Rumsfeld deplored the fact that the pictures had been shown at all, and then talked about charges of “abuse,” which, he believed, “technically is different from torture.” The word “torture” was carefully avoided by both men. President Bush, confronted much later with questions about a damning Red Cross report about the use of torture by the CIA, spelled out his view: “We don’t torture.”[1]

Susan Sontag, writing in The New York Times Magazine, had a different take on the pictures. She thought the “torture photographs” of Abu Ghraib were typical expressions of a brutalized popular American culture, coarsened by violent pornography, sadistic movies and video games, and a narcissistic compulsion to put every detail of our lives, especially our sexual lives, on record, preferably on public record. To her the Abu Ghraib photos were precisely the true nature and heart of America. She wrote:

Soldiers now pose, thumbs up, before the atrocities they commit, and send the pictures to their buddies. Secrets of private life that, formerly, you would have given anything to conceal, you now clamor to be invited on a television show to reveal. What is illustrated by these photographs is as much the culture of shamelessness as the reigning admiration for unapologetic brutality.[2]

Many liberal-minded people would have shared instinctively not only Sontag’s disgust but also her searing indictment of modern American culture. One of the merits of Errol Morris’s new documentary on the Abu Ghraib photographs, and even more of the excellent book written by Philip Gourevitch in cooperation with Morris, is that they complicate matters. What we think we see in the pictures may not be quite right. The pictures don’t show the whole story. They may even conceal more than they reveal. By interviewing most of the people who were involved in the photographic sessions, delving into their lives, their motives, their feelings, and their views, then and now, the authors assemble a picture of Abu Ghraib, the implications of which are actually more disturbing than Sontag’s cultural critique.

At first no one knew the dead man’s name. He was one of the “ghost prisoners,” brought into the “hard site” of Abu Ghraib by anonymous American interrogators, dressed in black, also known to the MPs as “ghosts.” These ghosts belonged to the OGA, Other Government Agency, which usually meant the CIA. Ghost prisoners were not formally registered before their interrogation in shower cubicles or other secluded parts of the prison. They disappeared as swiftly as they came, after the ghost interrogators were done with them. All that the MPs heard of their presence were screams in the night. If the Red Cross visited, the ghost prisoners were to be hidden away.

The man who would soon die arrived in the night before the photographs published in The New Yorker were taken, with a sandbag over his head, and nothing but a T-shirt on. MPs were told to shackle his hands to a window behind his back in “a Palestinian hanging position” (a technique allegedly used but certainly not invented by the Israelis). The man was breathing heavily. Then the MPs were dismissed. An hour or so later, they were called back in to help. The prisoner was no longer responding to questions. They hung him higher and higher, until his arms seemed at breaking point. Still no response. A splash of cold water. His hood was lifted. The MPs noticed that his face had been reduced to a bloody pulp. He had been dead for some time. The ghosts quickly left the scene. Medics were called in to clean up the mess, bandages were put over his puffed-up eyes, and the corpse was zipped into an ice-filled body bag and left in a shower room until it could be removed. The officer in charge of the MPs at Abu Ghraib, Captain Christopher Brinson, declared that the man had died of a heart attack.

Meanwhile, in the same prison block, another torment was taking place. Another nameless prisoner had been brought in, suspected of having killed an agent from the US Army’s Criminal Investigative Division (CID). He refused to divulge his name, so he was handed over to Specialist Charles “Chuck” Graner, an army reservist. Graner, a hulking mustachioed figure, seen laughing at the misery of Iraqi prisoners in many Abu Ghraib pictures, was not trained as an interrogator; nor did he have more than the vaguest idea of the rules and conventions that are supposed to guide interrogations. A corrections officer in civilian life, Graner enjoyed a “bad boy” reputation, with a taste for sinister pranks and an eye for the girls. He should never have been put in charge of terror suspects. He did not even have the security clearance to be a military policeman with custody over prisoners.

Nonetheless, Graner was put in charge of the nameless prisoner and told by CID agent Ricardo Romero to “make his life a living hell for the next three days and find out his name.” Graner did his best, aided by Sergeant Ivan Frederick and other members of their Maryland reserve unit who happened to be around and were equally untrained in interrogation work. The prisoner was stripped of his clothes, yelled at, made to crawl on the floor, deprived of sleep, forced to stand on a tiny box, hooked up to wires sticking from the wall and told he would die if he so much as moved. This last game lasted for about fifteen minutes, long enough for Graner to take his photographs.

Morris didn’t manage to interview Graner. He is still in a military prison. But other witnesses of what happened that night, such as Specialist Sabrina Harman, claim that not much harm was done to the prisoner they nicknamed “Gilligan.” She said that he ended up laughing at the Americans, and actually became a popular guy of sorts, being given the privilege of sweeping up the prison cells. “He was just a funny, funny guy,” she said. “If you were going to take someone home, I definitely would have taken him.”

Sabrina Harman also happens to be the young woman in the second picture, hunched over the corpse. Like Graner, she worked as a guard on the night shift at Abu Ghraib. Harman is described by other interviewees in Morris’s film as a sweet girl who, in the words of Sergeant Hydrue Joyner, “would not hurt a fly. If there’s a fly on the floor and you go to step on it, she will stop you.” The reason she joined the army was to pay for college. Her dream was to be a cop, like her father and brother. Not just a cop, but a forensic photographer. She loved taking pictures, with a special interest in death and decay. Another prison colleague, Sergeant Javal Davis, said: “She would not let you step on an ant. But if it dies, she’d want to know how it died.”

So when water started seeping out of the locked shower cell, and she and Graner uncovered the dead man in his body bag, her first instinct was to take pictures. She told Morris and Gourevitch that she

kind of realized right away that there was no way he died of a heart attack, because of all the cuts and blood coming out of his nose. You don’t think your commander’s going to lie to you about something. It made my trust go down, that’s for sure.

This is when Graner asked her to pose with the body. Harman adopted the pose she always did in photos, with her friends, with prisoners, in the morgue, and now in the shower: she grinned and stuck her thumb up.

Later, she returned to the same place alone, curious to find out more. She took off the gauze over the dead man’s eyes and “just started taking photos of everything I saw that was wrong, every little bruise and cut.” She realized how badly the man had been beaten up:

It looked like somebody had either butt-stocked him or really got him good, or hit him against the wall…. I just wanted to document everything I saw. That was the reason I took photos. It was to prove to pretty much anybody who looked at this guy, Hey, I was just lied to. This guy did not die of a heart attack. Look at all these other existing injuries that they tried to cover up.

In her interview with Morris, Harman looks rather impressive: intelligent, articulate, plausible. The interviews are actually more like monologues, for with rare exceptions Morris’s questions are never heard. His genius is to get people to talk, and talk, and talk, whether it is Robert McNamara in The Fog of War or Sabrina Harman in Standard Operating Procedure. The fact that he paid some of his interviewees for their time has been held against Morris by some critics. It seems of little importance. There is no reason to believe that cash changed their stories. If only the film had stuck to the interviews. Alas, they are spliced together with gimmicky visual reenactments of the scenes described in words, which take away from the stark air of authenticity. But perhaps that is Morris’s point. Authenticity is always elusive. Nothing can be totally trusted, not words, and certainly not images, so you might as well reimagine them.

But I think we are meant to believe that Harman is telling the truth. Her letters from Abu Ghraib to her lesbian partner, Kelly, suggest as much. On October 20, 2003, she wrote about a prisoner nicknamed “the taxicab driver,” naked, handcuffed backward to the bars of his cell, with his underwear over his face:

He looked like Jesus Christ. At first I had to laugh so I went on and grabbed the camera and took a picture. One of the guys took my asp and started “poking” at his dick. Again I thought, okay that’s funny then it hit me, that’s a form of molestation. You can’t do that. I took more pictures now to “record” what is going on.

Two pictures, then. The first one, of Gilligan and the electric wires, was analyzed by Brent Pack, a special forensic expert for the CID. After much thought, he concluded:

I see that as somebody that’s being put into a stress position. I’m looking at it and thinking, they don’t look like they’re real electrical wires. Standard operating procedure?that’s all it is.

He was technically right. A memo drawn up by the Pentagon’s general counsel, William J. Haynes, on November 27, 2002, recommending authorization of interrogation techniques in Category II?which included humiliation, sensory deprivation, and stress positions?was formally approved by the secretary of defense. Donald Rumsfeld even scribbled his famous quip at the bottom of this memo, stating: “However, I stand for 8?10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to 4 hours? D.R.”[3]

And yet this picture, more than any other, including the ones featuring attack dogs and wounded naked bodies, became the most notorious, an icon of American barbarism, the torture picture par excellence, perhaps because, as Gourevitch writes, it left so much to the imagination. That, and its evocation of the crucifixion, Christ at Abu Ghraib. And Sabrina Harman? She was sentenced to six months in prison, a reduction in rank to private, a forfeiture of all pay and allowances, and a bad conduct discharge. None of the men who were responsible for her subject’s death were ever prosecuted. No one above the rank of sergeant was even tried. As Morris said in an interview to promote his film, Harman and her friends caught in the photographs

were punished for embarrassing the military, for embarrassing the administration. One central irony: Sabrina Harman was threatened with prosecution for taking pictures of a man who had been killed by the CIA. She had nothing whatsoever to do with the killing, she merely photographed the corpse. But without her photographs we would know nothing of this crime.

It was just another death of a ghost delivered by ghosts.

2.

Morris has been faulted for not pointing his finger more directly at people more senior than Harman, Graner, Frederick, or Lynndie England, Graner’s girlfriend at the time, who held the naked prisoner on a leash. But this is missing the point of the film. For it is not about Washington politics or administration lawyers, or at least not directly, but about a particular kind of concealment, the way photographs which seem to tell one story actually turn out to hide a much bigger story. Compared to what was really happening at Abu Ghraib, where men were tortured to death in hidden cells, where children were incarcerated with thousands of other prisoners, most of them blameless civilians, exposed to daily mortar attacks, living in unspeakable conditions of filth and squalor, where there was no way out even for men who had been declared innocent, where unarmed prisoners were shot dead by nervous guards?compared to all that, the photograph of Gilligan was just fun and games.

The first thing human beings do when the unspeakable becomes standard operating procedure is to change the words. Even the Nazis, who never seemed to have been unduly bothered by what they did, invented new words, usually of a cold bureaucratic nature, to conceal their crimes: “special treatment” and so on. In public, the US policy toward “security detainees” or “unlawful combatants,” to whom, according to White House and Pentagon lawyers, the Geneva Conventions did not apply, was couched in the kind of language favored by Vice President Dick Cheney: “We need to make certain that we have not tied the hands, if you will, of our intelligence communities in terms of accomplishing their mission.”

The phrase “the gloves are coming off” gained currency. As in an e-mail, quoted by Gourevitch, sent to MI unit commanders in Iraq by Captain William Ponce of the Human Intelligence Effects Coordination Cell: “The gloves are coming off gentlemen regarding these detainees. Col. Boltz”? Colonel Steven Boltz, the deputy MI commander in Iraq?”has made it clear that we want these individuals broken.” The likes of Harman, Graner, England, and Frederick were at the very bottom of the chain of command. They were told to “soften up” the prisoners, to make their lives hell. They should “treat the prisoners like dogs,” in the words of Major General Geoffrey Miller, commander of the prison and interrogation camp at Guant?namo Bay. He said this before the photographs were taken, during a visit to Abu Ghraib, where he felt the prisoners were treated too well. His methods, honed at Guant?namo, were soon adopted. One of Morris’s (or Gourevitch’s) more arresting ideas is that the photographs of the treatment meted out to the prisoners are evidence that the people who were ordered to take their gloves off, if you will, had not entirely lost their moral way. Gourevitch writes:

Even as they sank into a routine of depravity, they showed by their picture taking that they did not accept it as normal. They never fully got with the program. Is it not to their credit that they were profoundly demoralized by their service in the netherworld?

Credit is perhaps not the mot juste. Nazis who took pictures of naked women lined up in front of their own mass graves might not have considered the scene quite normal either, but this does not mean that they were not with the program. Heinrich Himmler was well aware that what he was asking from his SS men was not normal. That is why he told them to steel themselves against any feelings of humanity that would hamper them in their necessary task.

That Harman, for one, was often disgusted with what she saw at Abu Ghraib is indeed clear from her letters to her partner, Kelly. And even Graner, the baddest of the bad apples, was apparently taken aback when he was told by “Big Steve” Stefanowicz, a contract civilian interrogator, just how roughly prisoners were to be “broken.” Graner was reminded of 24, the popular television series, starring Kiefer Sutherland, about the necessity of using any means, including torture, to stop terrorists. Graner claims that he told Big Steve: “We don’t do that stuff, that’s all TV stuff.” Graner was surely unaware that 24 had actually been discussed in all seriousness at brainstorming sessions at Guant?namo led by the staff judge advocate, Lieutenant Colonel Diane Beaver. She recalled the mounting excitement among her male colleagues, including men from the CIA and the DIA, as different interrogation techniques were being bandied about. She told Philippe Sands, author of Torture Team: “You could almost see their dicks getting hard as they got new ideas.”

That was in Guant?namo, where ideas were hatched, noted on legal pads, recorded in memos, debated in air-conditioned offices. Now back to Graner in the filth, noise, and menace of constant violence in Abu Ghraib prison. As the authors point out, there is a kind of pornographic quality to many of the pictures which would indicate that Susan Sontag’s cultural critique was not entirely off beam.

The deliberate use of women, for example, in the humiliation of Arab prisoners is striking. Graner may have asked his girlfriend, Lynndie England, to pose for a picture holding a prisoner on a leash. This might have given him, and possibly her, an erotic frisson. And Sabrina Harman, too, is seen to have been a grinning accomplice in several of Graner’s pranks with naked prisoners. That is why she ended up being convicted. But in fact these games?some clearly staged for the camera as cruel photo-ops?were also part of the program. The women’s panties, the nudity in front of women, the poking of the genitals, the enforced simulation of sexual acts, were all part of the program. Graner was told in writing by his commander, Captain Brinson, that he was “doing a fine job.” He was told: “Continue to perform at this level and it will help us succeed at our overall mission.”

The MPs at Abu Ghraib, as Gourevitch rightly observes, knew little about Middle Eastern culture, but they were given “cultural awareness” training at Fort Lee, before being flown out to Iraq. They were told that sexual humiliation was the most effective way to “soften up” Arab detainees. A person does not have to be corrupted by the popular culture deplored by Susan Sontag to be vulnerable to feelings of pleasure when the sexual humiliation of others is officially sanctioned, even encouraged. Graner’s real sin for the administration was not that he went too far (which, measured by any moral yardstick, of course he did), but that he took pleasure in what should have been a grim job. As Dick Cheney said: “It is a mean, nasty, dangerous, dirty business out there, and we have to operate in that arena.” Hard dicks should have been kept strictly out of sight, under conference tables. But Graner turned the dirty business into his own pornographic fantasies; and what is worse, he recorded them on film, for all the world to see.

Lynndie England played a walk-on part in these fantasies. She loved Graner. She would have done anything he wanted. That was her tragedy. England was sentenced to three years in a military prison for maltreating detainees. “All I did was what I was told to do,” she said, in the oldest defense of men and women landed with the dirty work. “I didn’t make the war. I can’t end the war. I mean, photographs can’t just make or change a war.”

Harman, too, acted out her fantasies, of being a forensic photographer, of recording death. As a result, she made the program public, and forced the president of the greatest power on earth to issue a public apology. As Morris says, in his interview: “Under a different set of circumstances, you could imagine Sabrina winning a Pulitzer Prize for photography.” Instead, she was charged not only with dereliction of duty and maltreatment, but with destroying government property and “altering evidence,” by removing the bandages from the dead man’s eyes. She told Morris: “When he died, they cleaned him all up, and then stuck the bandages on. So it’s not really altering evidence. They had already done that for me.” Since her pictures revealed the truth of this statement, these particular charges were eventually dropped.

Both Morris’s film and the book based on it by Gourevitch are devastating, even without going into detail about the complicity, or indeed responsibility, of top officials in the Bush administration. The photographs embarrassed the United States, to be sure. But for the US government, this embarrassment might have actually helped to keep far greater embarrassments from emerging into public view. Preoccupied by the pornography of Abu Ghraib, we have been distracted from the torturing and the killing that was never recorded on film and from finding out who the actual killers were. Moral condemnation of the bad apples turned out to be a highly useful alibi. By looking like a bunch of gloating thugs, “Chuck” Graner, Ivan Frederick, et al. made the law-yers, bureaucrats, and politicians who made, or rather unmade, the rules?William J. Haynes, Alberto Gonzales, David S. Addington, Jay Bybee, John Yoo, Douglas J. Feith, Donald Rumsfeld, and Dick Cheney?look almost respectable.

And Gilligan, by the way, was probably not the man anyone thought he was after all, but an innocent who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Just like up to 90 percent of the men and boys locked up in Abu Ghraib.

'We want to know'

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Kalpana Chakma’s unresolved abduction 20 years on…

Photographs and interviews by Saydia Gulrukh

Kalindikumar Chakma (Kalicharan)

Kalpana?s eldest brother

?The hill people do not get justice, look at Yasmin, some justice was done, but people of the hills don?t get any justice. It?s been twelve years…The VDP [Village Defence Party] member Nurul Huq, and Saleh came with Lieutenant Ferdous to this house that night. They still strut around. They live in the neighbouring Bengali village. Go there. You will find them. I have told the BDR [Bangladesh Defence Rifles] commanding officer, you say you can?t find him, well, his accomplices are around, why don?t you question them?

Kalpana?s clothes kept in her brother Kalicharan?s home

?She had a black bag, she took it to Dhaka. I have kept all her things in it. All these years. But the mice have been at it. She had many books… I educated her up to I.Com, I got her admitted to the degree classes, I thought our lives would become a bit better, but no, they came and took her away… I do not know to this day whether she is dead or alive… They should at least tell me that she has died so that we can give dharma, do what religion asks of us. People of all religions have a right to do what should be done.?

Mithun Chakma

Kalpana Chakma?s comrade

?I was picked up by the army when I was delivering a speech at a PCP rally, on the 6th of August 2004. They took me to Khagrachari camp, blindfolded me, took me to a room, asked me to lie down [on a bench], put up my legs, then they began beating me on the soles of my feet with the butt of a hockey stick. They beat me for a long, long time, they said things like, ?What is your name? What do you do?… [Why do] you take up arms? What are your ideals?? Lots of other things, ?You do not know that we ? the army ? have learnt how to torture, we have had training from the US.? They also said other things, ?And the Kalpana thing, well we did that, but nothing happened, right???

The well in New Lallyaghona village, in front of Kalpana?s house

?They brought Kalpana and her two brothers to this well, and blindfolded them… I think they pushed them over to that beel [marshes]. They got her to enter the waters, and then shot her… [The next day] villagers scoured the waters all day long with fishing nets. But her dead body was not found.?

by Meghna Guhathakurta

Kalpana, a first year graduate student of Baghaichari College, was a conscious, vocal and hardworking activist who fulfilled her role as organising secretary of the Hill Women?s Federation with commitment and resolve. Systematic and pervasive military presence in the hill tracts has made Pahari women more conscious of their rights. This is vividly borne out by what Kalpana writes in her diary, recovered by journalists from her home after her disappearance. Parts of this diary were serially published in the Bengali daily Bhorer Kagoj. Later, it was reprinted along with other writings in an anthology, Kalpana Chakma?s Diary, published by the Hill Women?s Federation (2001).

Kalpana introduces her ?daily notebook? through the following lines: ?Life means struggle and here are some important notes of a life full of struggle.? In depicting the life of a woman in the CHT, she writes, ?On the one hand, women face the steam roller of rape, torture, sexual harassment, humiliation and conditions of helplessness inflicted by the military and Bengalis. On the other, they face the curse of social and sexual discrimination and a restricted lifestyle.? However, Kalpana?s understanding of oppression embraces all women of Bangladesh, ethnic and Bengali. She writes elsewhere: ?I think that the women of my country are the most oppressed.? In expressing her yearnings for freedom from oppression she uses a beautiful metaphor: ?When a caged bird wants to be free, does it mean that she wants freedom for herself alone? Does it also mean that one must necessarily imprison those who are already free? I think it is natural to expect the caged bird to be angry at those who imprisoned her. But if she understands that she has been imprisoned and that the cage is not her rightful place, then she has every right to claim the freedom of the skies!?

Kalpana?s reading of the woman question is a feminist one. Her feminism allows her to look at the woman question in terms of Bengali domination, as well as in terms of sexual politics within her own community. This is striking and unique since in most nationalist or ethnic movements the gender question becomes a subtext to the larger ?national? one. Kalpana?s feminism differs sharply from that of her middle-class Bengali sisters. Her struggle, unlike theirs, pitches her to confront military and racial domination in a manner incomprehensible to most privileged Bengalis. ***

Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics

Brill Academic Publishers, 2005

By Suad Joseph and Afsaneh Najmabadi

IN THE late 1980s conflicts of state versus community were sharply on the rise. In Bangladesh problems over the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) from 1980 led to a series of massacres, plunders and destruction of villages… [this conflict] had historical roots [it] became particularly violent in the 1980s and 1990s…in all these movements women played an important role in conflict resolution.

People in the CHT were antagonistic toward the government of Bangladesh from the time the Kaptai dam was built (1957-62) and thousands of people became homeless. In the early 1970s the whole of CHT was brought under military control. The original inhabitants of the CHT were the Jumma (tribal) people. They were aggrieved not just because of the dam but also because the state had undertaken to change the demographic balance of the region through a policy of settling Bengali Muslim people from the plains in the CHT. The protest of Jumma people brought forth severe counter-insurgency measures leading to extra-judicial killings and massacres by the state. The rebels also formed a military unit called the Shanti Bahini. In all of this the tribal women were targeted; this was dramatically brought to the fore by the abduction of Kalpana Chakma in 1996. While the region was being torn apart the Hill Women?s Federation (HWF), a secular women?s organization was formed in 1989 by women students of the Chittagong University. By 1991 it had become extremely popular…The main aims of these groups were justice for the tribal people of CHT and an end to violence. They were among the strongest voices for peace.

by Mithun Chakma

ON THE night of 11 June, 1996… Barely 7/8 hours [later] voting for the seventh National Parliamentary Elections [begin]…at about 1:30am..Mrs. Bandhuni Chakma, Kalpana?s widowed mother got out of bed and opened the door, her whole body was trembling in fear. They came out one by one: Kalpana, her two brothers, Khudiram and Kalicharan, the latter?s wife. The house was surrounded… A soldier flashed a torch on their faces, and Kalicharan recognised Lieutenant Ferdous, who had visited their house a few days back, and two VDP members ? Nurul Haque and Salah Ahmed. Amnesty International in an Urgent Action issued on 1st July 1996 wrote: ?Six or seven security personnel in plainclothes, believed to be from Ugalchari army camp (actually Lieutenant Ferdous was commander of Kojoichari Army camp), are reported to have entered the home of Kalpana Chakma in New Lallyaghona village, Rangamati district in the early hours of 12 June. Kalpana Chakma and two of her brothers were forcibly taken from their home, blindfolded and with their hands tied.?

What happened? The Ain-o-Salish Kendra report [says], They (army) took Khudiram near a lake and told him to step into the lake. As soon as he went in, the order to fire was given. Frightened, Khudiram took shelter in the water. He swam around for some minutes, then rose up and took shelter in a neighbour?s house, he had no clothes on his body. In the meanwhile, armed personnel blindfolded Kalpana and her brother Kalicharan. He heard the firing, ran and managed to escape. While running to save his life he heard two shots being fired, and heard Kalpana screaming. Kalicharan said, ?They shot at me and when I ran I could hear Kalpana crying out Dah Dah Mare Baja (Brother, brother save me!)…?

A cover-up attempt was made from the very beginning. Initially, the army termed it a ?love affair? [between Lieutenant Ferdous and Kalpana Chakma]. However, they backtracked later, and flatly denied their involvement in the abduction. When the issue refused to die down, they launched a vicious disinformation campaign. The Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission in its report Life is Not Ours (update 3) said, an NGO named Bangladesh Human Rights Commission declared at a press conference on 15th August 1996: Kalpana Chakma had been seen in Tripura (India), she herself had plotted her own abduction. Kalpana Chakma?s mother rejected BHRC?s statement and termed it a ?blatant lie?.

After months of protest and mounting international condemnation, the government constituted a three-member inquiry committee on 7 September 1996, headed by Justice Abdul Jalil. The other members were Sawkat Hossain, Deputy Commissioner of Chittagong and Dr. Anupam Sen, professor of Chittagong University. The committee is reported to have submitted its findings to the Ministry of Home Affairs a couple of years ago, but the government has still not made it public.

Meanwhile, a storm of protests swept the CHT. A general strike was observed in Marishya, the area to which Kalpana belonged. While the Jummas wholeheartedly supported the programme, some Bengali settlers attacked a rally, and shot dead 16-year old Rupon Chakma. The settlers also hacked to death Sukesh Chakma, Monotosh Chakma and Samar Chakma, on their way to Baghaichari bazaar to take part in picketing.

Lieutenant Ferdous, [allegedly] the mastermind behind the kidnapping, is reported to have been promoted to the rank of Major and posted back to Karengatoli army camp, not far from New Lallyaghona, Kalpana Chakma?s village.

Mithun Chakma is general secretary, Democratic Youth Forum. Edited excerpts from http: //jummonet.blogspot.com/2007/06/11th-year-of-kalpana-chakma-abduction.html

Sonali Chakma

President

Hill Women?s Federation

Kalpana Chakma will always remain a symbol of resistance in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The army?s attempt to silence Jumma women by kidnapping Kalpana in the dead of night has failed and will always fail. She will continue to inspire generations of women activists in the country.

It is regrettable that the inquiry report has not been made public after twelve years of her disappearance. We demand that the report be published without further delay and Lieutenant Ferdous, the [alleged] mastermind, and his accomplices be punished.

Sultana Kamal

Former adviser, caretaker government

Executive Director

Ain O Salish Kendra

Nearly twelve years ago we lost Kalpana Chakma, a person, a co-worker and a human rights activist. Her absence hurts us immeasurably. It evokes feelings of losing a friend, but not only that, it also raises questions about our nation?s conscience. Many of us have tried our best, we have made repeated appeals to the state, but to no avail. We have no reason to believe that effective steps have been taken.

If Kalpana is still alive, we would like her to know that we still remember her, that we look forward to her return. If she is not, if our worst fears are true, that she was murdered after being abducted, we want to stress that if we fail to realise her dreams, we fail to live up to our convictions.

Khaleda Khatoon

Human rights activist

Long live Kalpana, you have given voice to the protests of Pahari women. We need you. We need more women like you. We need leaders like you.

I want to raise two issues: first, a case was registered against Lieutenant Ferdous. Why is that not being revived, does the current government not have any responsibilities in this regard? I say this especially since Devashish Ray as special assistant to the chief adviser is now part and parcel of the government.

Second, the Kalpana Chakma abduction committee report has not yet been released. Since the caretaker government is considering a Right to Information Act, I would like to propose that they begin their journey by making this report public.

Moshrefa Mishu

Convener

Garments Sramik Oikya Forum

On the twelfth anniversary of Kalpana Chakma?s abduction, I demand that the incident be investigated urgently, without any prejudice or fear, so that we can learn what really happened, and that her family be provided security.

I also demand that the army be withdrawn from the Chittagong Hill Tracts and that the hill region be made autonomous. The person(s) who abducted Kalpana must be tried. We must keep Kalpana?s memory alive, and demand that justice be done. We must pay respect to her through re-creating her struggles.

I salute you Kalpana Chakma.

Anu Mohammed

Professor

Department of Economics

Jahangirnagar University

Kalpana Chakma?s abduction urges us to look again at the nature of the Bangladesh state. Kalpana belongs to a group of people fighting against ethnic domination, a group struggling hard to be rid of the army?s suffocating grasp. She has been missing for the last twelve years. An investigation committee was formed but all those accused were successfully hidden from public view. Inequalities, oppression, discrimination continue to exist in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and so does the struggle.

Kalpana Chakma is a symbol of protest and resistance. She will remain so forever.

Maheen Sultan

Member

Naripokkho

The struggle of the indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts for the protection of their lands, identity and cultural heritage is an ongoing one. Of the many violations suffered, the disappearance of Kalpana Chakma is one that drew attention of the human rights and women?s rights movement in Bangladesh. Twelve years on, her disappearance is still a puzzle. Demands for an official enquiry, like all other national enquiries, resulted in nothing. It is ironic that while much lip service is paid to good governance and transparency, the public has never been presented with the findings of the enquiry. The lack of transparency is particularly acute in the case of the defence forces. Just as ordinary citizens are in the dark about the defence budget and expenditures, so are we in the dark about the militarisation of the CHT, and whether any actions have been taken against the innumerable wrongs committed against our own peoples, simply because they are not Bengali.

We demand that the present government make the enquiry report public, so that justice can be done.

New Lallyaghona

1/4/96

Shaikat Da,

Greetings. I got your letter yesterday. We are in good health. But I feel unsure. Something terrible might happen any moment. I am very worried.

News from here ? on 28.2.96 a miscreant called Ishak was taken away. Since then the Bengalis have been wanting to attack the Paharis. In this agitated situation, the third annual conference of Pahari Chhatra Parishad?s branch was successfully held on 7.3.96 (according to its earlier schedule). A nineteen-member Thana Committee has been formed with Purba Ranjan as the President, Dharanimoy, its Secretary, and Prabir, its Organising Secretary. The Baghaicchori branch held a cultural programme for the first time, where the 1988 play Norok was staged.

And [news from] there, Bengali agitation has increased since 11.3.96. They have been holding meetings and processions. Paharis have become fearful, ?ready to flee? at any moment. But I was not here. I had gone to Barkal on organisational work. I returned on the 13th and heard the details. Bengalis have forbidden Paharis from entering the bajar area or Bengali neighbourhoods, they have even forbidden Paharis to talk to Bengalis. After this, the work of uniting Paharis began. In other words, resisting attacks in the whole Kassalong area. Guarding at night has begun. On the other hand, Lieutenant Ferdous, the army camp commander of our village, has made false promises to village elders, and held meetings with them. Many other incidents, small in nature, have kept occurring. Especially, since the Bengalis have targetted four of our neighbouring villages including Battala.

In this situation, on the 19th of March, cries were heard all over Kassalong, and that infamous Lieutenant Ferdous came to our New Lallyaghona village and burnt down 9 homes that belonged to 7 families. They beat up the Pahari nightguards most severely. After this, the DC, SP and Communications Committee (JSS) Secretary Mathura Lal Chakma had meetings which calmed the situation somewhat. They were told that if Ishak was not released by the 5th [of April], Bengalis were likely to muddy the waters further. The DC and SP are unable to bring the situation under control. At present, people are fearful of what might happen after the 5th. We are leading uncertain lives.

It is Bengalis who are behind this agitation and this time we have been able to teach them a lesson. Usually, Paharis flee from their villages but now they go to those very places from where you can hear cries. Bengalis, indisciplined as they are, have been taken aback at this unity and are afraid, along with the others. The administration has also witnessed this unity.

The present situation: Baghaicchori is isolated from all other parts. Chakma telephone lines have been cut, Paharis are not given access to other lines. We are not allowed to go to the marketplace. Maybe there will be no postal communication until the situation calms down. Maybe there will be no letters even.

That?s all for now. Lastly, I send you advanced Boishabi greetings.

Yours

KC

PS: I wrote this letter hurriedly. If my sentences are awkward, please correct them.

Shaikat Dewan is a member of Pahari Chhatra Parishad. Source: Kalpana Chakmar Diary, Dhaka: Hill Women?s Federation, 2001, pp. 69-70.

1993-1996

1993? Kalpana?s political life began as women?s secretary of Baghaichari Pahari Chhatra Parishad.

March 1993? took on responsibilities of the convening committee, Hill Women?s Federation, Marishya branch.

January 15, 1995? took part in the first central conference of the Hill Women?s Federation, Khagrachari.

May 21, 1995? Kalpana is elected organising secretary of the central committee at the HWF conference, held in Khagrachari.

November 17, 1995? meeting of three Pahari organisations held in Naniarchar Khedarmara High School premises to express grief and outrage at Naniarchar killings in Rangamati. Kalpana addresses the meeting.

February 28, 1996? Ishak, a Bengali, is abducted from New Lallyaghona village. Tension increases between Paharis and Bengalis.

March 19, 1996? Nine houses belonging to seven Chakma families of New Lallyaghona village burnt down. Kalpana protests against the arson attack.

April 1996? Lieutenant Ferdous goes to Kalpana?s house a few days before Baishabi (New Year festivals). He is accompanied by 20-25 soldiers. Heated exchange between Kalpana and Lieutenant Ferdous.

April 12, 1996? meeting of three Pahari organisations held at the Rangamati Shilpakala Academy on the occasion of Baishabi. Kalpana appeals for unity.

June 12, 1996? at 1:30am Lieutenant Ferdous and 7-8 others in plainclothes enter Kalpana?s house, they order her, and her brothers Khudiram and Kalicharan, to go with them.

This chronology has been constructed from letters, news reports, and `Investigating the Kidnapping of Kalpana Chakma?, Ain O Salish Kendra Report, published in Kalpana Chakmar Diary (Diary of Kalpana Chakma), Dhaka: Hill Women?s Federation, 2001

First published on New Age 12th June 2008

Un-intelligent manoeuvres: tales of censorship

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Rahnuma Ahmed

Calling for an end to the emergency rules, editors and senior journalists of the print and electronic media yesterday protested against the interference of government and military agencies in the everyday task of the media. ..[t]he media has to work under limited rights, pressure and in fear of fundamental-rights-denying emergency rules since the president declared the state of emergency on January 11 last year.

VOA News, May 14, 2008

My Dilemma

IN THESE times, writing or speaking in defiance of censorship is often viewed with a tinge of suspicion. There must be higher-up backing. Or else, how could she, how could he… One also comes across those who say, see, this proves there is no Emergency. Not in the strict sense of the word. This government is not like any other government. They are different.

Times must be pretty hard, I think, when a generalised suspicion passes for analysis. When sycophancy becomes second nature. The problem with Emergency is that it breeds irresponsibility. Our rulers know what is best for us. We will speak up after the government has set the house in order, after things have been sorted out. After the elections are over. After Emergency has been lifted. After this, after that ? it is a list that trails off into an indefinite future.

Too much abdication, too many ifs. Not only that. Emergency breeds a culture of fear. People are more likely to keep their mouths shut, to sound non-committal, to adopt an I-mind-my-own-business attitude, to churn out uniform phrases. The recent joint statement of the editors and senior journalists of Bangladesh (May 13, 2008), speaks of continuous monitoring and interference in the day-to-day running of print and electronic media, to a point where, as Nurul Kabir, editor of New Age put it, editors are no longer able to make ‘independent’ decisions.

And the source of interference? Some newspaper reports said, the editors spoke of ‘government agencies.’ In a daily I read, ‘civilian and military agencies.’ Yet another spoke of ‘government and military agencies’. A Daily Star report went a bit further, it said the editors had spoken of ‘a military intelligence agency’ (May 16, 2008), I saw people sitting up and taking note of the series of meetings being held at the National Press Club. I heard people utter the words `DGFI’, but I didn’t see it in print. I also heard, things are going to change from now on, heavy-handedness is likely to lessen, the editors’ demand created ripples. This, however, remains to be seen.

Since the declaration of Emergency, military interference in the print media has concentrated on changing priorities, on overseeing that particular news stories get reported, that others go unreported, or under-reported. These pressures are the more visible ones. But infiltration has occurred in more devious ways. A prime example is provided by confessions of politicians who allegedly pocketed public wealth. Most of these `confessions’, made under remand, have been printed in the dailies with tremendous enthusiasm. Not only in the tabloids, in the more serious papers too, without any mention of sources. As if the confession was made to the reporter, in person. A blogger has termed this “crossfire journalism,” because of its deafening one-sidedness. The accused is not given the opportunity of self-defense, to offer his or her side of the story. Interestingly, many of those accused have contested these confessions in court, they have claimed that these were made under duress. This does not seem to have caused much concern. I say this because I have not come across any retractions, nor have confessions ceased to be published. I have other concerns too. That the media does not sift through, that it does not investigate, that it reproduces whatever it is handed-out ? as long as it is from a particular source ? that I find very disturbing. Of course, not all newspaper editors have equally succumbed to the army’s campaign of calling the shots, but that is a separate issue.

In the case of private TV channels, interference has focused on news programmes, live discussion programmes, and also, nightly news review programmes, hosted mostly by journalists. In the latter two programmes, members of the audience raised questions. For instance, in Ekusheyr Shomoy, a panel of journalists acted as auditors to what the experts said. Many other programmes had live, viewer phone-ins. These features, in their own fashion, contributed to creating public spaces of democratic deliberation. (Of course, not all channels have been equally courageous, but that again, is a separate issue). From the interference that they face, it would seem that these spaces are perceived as threats. What does it threaten? Who does it threaten? These questions are sidelined, the emperor’s nakedness is not to be mentioned.

Military interference of these Emergency months has included a jealous guarding of its own image, of censoring photographs that threaten its sense of honour and dignity. Mahbubur Rahman, the former army chief was assaulted by party workers last year, strict instructions were given to newspaper offices that these photographs should not be published. The army has guarded its self-image of physical supremacy most viciously, as is symbolised by the furore over the photograph known as the `flying kick,’ taken during the Dhaka University student protests, in August 2007.

No timeline for the expiration of Emergency has been announced. Not yet. I would be lying if I said, everything seems to be fine, no deception seems to be involved. If I said, why worry?

Tales of censorship

The situation was far from ideal when political parties ruled the nation. Although newspaper ownership and content was not subject to direct government restriction, attacks on journalists and newspapers occurred frequently. Government efforts to intimidate them also occurred frequently. Political cadres would often attack journalists. Some were injured in police actions. For instance, according to a 2005 human rights report, 2 journalists were killed, 142 were injured, 11 arrested, 4 kidnapped, 53 assaulted, and 249 threatened. If one used similar indices of comparison for last year, the situation does not seem to have worsened. Thirty-five journalists were injured, 13 arrested, 35 assaulted, 83 threatened and 13 sued. A media practitioner was forced to sign an undertaking, another came under attack. (New Age, January 15, 2008).

But I think the terrain itself has changed, and hence, the terms of comparison need rethinking. Threats to the industry have surfaced that bring back older memories, Martial Law memories, even though we are constantly told that we have no reason to fear. These threats are substantial. The owners and directors of at least 5 TV channels, and 5 newspapers are facing ACC anti-corruption charges. The first and lone 24-hour news channel in the country, CSB, was taken off air last year, after the August protests. The closure of newspapers and TV channels, according to some observers, has broken the backbone of the media industry. It has caused massive unemployment among journalists, and others in media-related occupations. Wages are no longer regular. According to an insider friend, those working in a private TV channel received their wages and salaries for February last week only. In 5 or 6 newspapers, wages have not been paid for the last six months or so. The severe crisis in both print and electronic media is not only a financial one. In some senses, it is one of existence too. Existence as known thus far.

Journalists have been tortured for investigating security forces (Tasneem Khalil, Jahangir Alam Akash). It is rumoured that the owner of a private TV channel was picked up by security forces. He was left blindfolded, and released only after he had agreed to sign blank sheets of paper. Guidelines for talk shows have been issued. Names of blacklisted guest speakers have been circulated to private channels (white-listed ones too!). A faxed letter on plain paper asking Ekushey to close down its highly popular talk shows (Ekusheyr Shomoy, Ekusheyr Raat) was sent in end-January. Later, a similar letter was sent to most other channels. Sending plain paper directives, minus any letterhead, to newspaper and TV offices seems to be a new tactic of the military agencies. Leaving no footprints in the sand?

Tales of ownership

For the regime, the anti-graft drive has had some useful side-effects. The intelligence services are systematically acquiring shares in private media companies, by offering the release from detention of their owners in return.

The Economist, November 8, 2007

Is this true? Is there any way of verifying what is reported in the lines above? Why should the intelligence services buy up shares in the media industry? Any guesses?

Rumours have been floating of the intelligence agency brokering deals, of buying and selling shares in the media industry. If that’s true, how would that be in the public interest?

These are common enough questions that have bothered me, and all those I know who have read the article.

What intrigues me however is, the military intelligence agency already has vast powers at its disposal, powers that enable it to control the print and electronic media in this country, be a part of the conditioning factors that have led to the industry’s severe crisis, with an almost broken backbone, both financially and otherwise.

What further powers will ownership give? Should one look towards Pakistan’s milbus (military-business) to seek answers?

First published in New Age 20th May 2008

Unidentified terrorists in the hills

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

rahnuma ahmed

Some external terrorists from outside Sajek have set these fires. There is no conflict between Bengalis and Paharis in this area. Those who set the fire don?t want the current communal harmony between Bengalis and Paharis to stay intact. Since they want to create a terrorist center in this area, they try to keep both sides agitated.

Major Kabir, second-in-command, Baghaihat zone (Fact Finding Team 1. Moshrefa Mishu et al, Report on 20th April Incident at Sajek Union.)

Bengali settlement in times of Emergency

BY NEARLY all accounts, Bengali settlement in the Chittagong Hill Tracts has accelerated. It has intensified. Why?

Discovering the truth is never an easy task. More so, in times of Emergency. But our rulers forget, not everyone submits. ?A happy slave is the biggest threat to freedom,? says a postcard on my wall. Fortunately, the peoples of this land, neither Bengalis nor adivasis, have submitted. Never fully. Or, for long.

Five victims of Sajek ? Pahari villagers ? have come forward. They spoke out at a press conference in Dhaka, on April 27, 2008. Two separate fact-finding committees, consisting of writers, teachers, lawyers, student leaders and activists, human rights activists, left leaders, journalists, women?s group activists, visited the affected villages in Sajek, Rangamati. They spoke to Paharis and Bengalis. To settlers and civilians, to army personnel. They spoke to Paharis who had sought refuge in temples and forests after the arson attacks of April 20. Some still sleeping under open skies. They spoke to settler Bengalis too. To those who had taken refuge in the local market. To another settler, who had sought and found refuge in the nearby army camp itself. Those in the market were also being looked after by the army.

Bengali settler houses, Dui Tila, Sajek union. ?Udisa Islam, 27 April 2008.

Binoy Chakma, a Pahari victim, had said at the press conference, nearly ninety per cent of the villagers of Purbo Para, Gongaram Mukh, Retkaba, Baibacchora, the four Pahari villages that were burnt down, originally belonged to Longodu, Borkol, and Dighinala. But we were forced to leave our homes, said Binoy, because of army and settler attacks. Life in Baghaicchori, under Sajek union, was not easy. Army presence was continuous. It was stifling. But we managed. We managed to lead peaceful lives, to eke out modest livings. Things changed, however, with the declaration of Emergency, said Binoy. Warrant Officer Haroon told us, army posts will be built here. But later, small huts were built instead, in our land and garden. The settlers built them, the army helped them. We had set aside land for building a Buddhist temple, they took that away too. We protested, but they threatened us. Indra Chakma?s pineapple garden in Retkaba was destroyed. Ali, a settler, forcibly built a house on Indra?s land. Indra resisted, Ali and the soldiers dragged him to the army camp. If you protest again, they said, we?ll slaughter you like a sacrificial cow. There were other injustices, too. Rat infestation had left us with little food, the UNDP gave rice for 1,500 families. It was the UP Chairman L Thangar?s duty to distribute 20 kilograms for each family. But he gave only 8-10 kilograms to each Pahari family. When we asked him, he said, he had army instructions.

One of the fact-finding committee?s reports corroborates Binoy?s account, ??since 11 January 2007, the process of Bengali settlers grabbing Pahari land has accelerated.? It also says land grabbing and Pahari eviction is taking place under army supervision. A weekly review of the Asian Centre for Human Rights (April 23, 2008) reports similar trends, ?Since the imposition of the State of Emergency, the implantation of illegal plain settlers has intensified with the direct involvement of Bangladesh army.?

Between 1979 and 1983, Bangladesh?s military rulers sponsored migration of Bengali settlers into the Chittagong Hill Tracts. An estimated 500,000 plains settlers were provided land grants, cash and rations. As is clear from the Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission report, Life is not ours (1991), the programme of turning Paharis into a minority was not made public then. Government representatives had repeatedly denied the existence of such a plan.

What does one hear now? Bengali settlement in the CHT is a thing of the past. The 1980s, yes, that was the settlement era. It was a mistake. The military rulers failed to realise it was a political problem, it should not be dealt with by force. Things are very different now. Now you may find some Bengalis going to CHT, they are following their family members. That is not settlement. How can one stop that? It sounds nice, the only problem is that it isn?t true. Settlement is still active. It seems to be at a final stage. Ina Hume, a daughter of the hills, and a careful observer of military repression wrote in 2005, a new road has been built from Baghaihat to Sajek. It borders the Mizoram hills of northeast India. She adds, there have been reports that the Bangladesh Army is involved in settling a further 10,000 Bengali families in the Kassalong Reserve Forest in Sajek. The writers of Life is not ours had noted, Pakistan, and later, the Bangladesh government had been uneasy about the borders with India and Burma being inhabited by a majority of the hill peoples. The Sajek incident, it seems, was destined to occur.

Need I say that the proposed settlement of Bengali families in the Kassalong Reserve Forest is in direct negation of the 1997 Peace Accord? Or, that the construction of the Baghaihat-Sajek road by the Bangladesh Army Engineer Construction Battalion, in the Kassalong Reserve Forest, clearly violates the Forest Act of 1927, and the Bangladesh Forest (Amendment) Act, 2000?

Four stakes vs Pahari homes

Most media reports in the Bangladesh press have stressed that losses occurred on both sides. Most reports mentioned that a larger number of Bengali homes were razed to the ground.

The fact-finding committee reports have been invaluable in providing a truer account of what happened. The report of the fact-finding committee led by Sara Hossain contains vivid descriptions of what Paharis lost as a result of the attacks. A middle-aged Chakma villager of Balurghat Para had told the committee members, ?Our rice, clothes, pots-pans-plates have all been burnt. School books, birth registration certificates, SSC certificates, they?re all totally burnt.? Several eyewitnesses and victims had said that their valuables were looted first, the houses set on fire later. A Daney Bhaibachora villager who had been interviewed had said, ?The people who were setting things alight, they first took out from our homes, the TVs, beds, wardrobes, whatever they found, they looted, and at the end they torched the houses. Those who set the houses alight. They took everything.? A Chakma woman had added, ?I?ve heard that a TV was found in the Bangali Para. The Army has said that they will return the TV.?

Bengali settler houses, Dui Tila, Sajek union. ?Udisa Islam, 27 April 2008.

The other committee report, the one led by Moshrefa Mishu, is also invaluable. It fleshes out what the Bengalis settlers lost. According to the writers, Bengali settler houses are temporary shelters. They consist of four stakes (khuti) pegged to the ground. There are hundreds of such homes in the Dui Tila area. They write, we spoke to Bengali inhabitants, who told us that they live here for short periods only. The report says, land grants to Bengali families are parcelled into smaller pieces meant for habitation, close to army camps, and larger pieces, located in far-away places. The report states, ?…most Bengalis have two houses… Dighinala and Lichu Bagan are 12 kilometres apart…We interviewed settlers who told us that they had received 4 acres and 1/70th land in Lichubagan, and the remaining 1/30th land on Betcchari.? The writers go on, it was the same in Dui Tila and Chongracchori. Settlers told us, they had 1/30th of an acre here, the rest, 4 acres and 1/70th land in distant mountainous areas.

Communal harmony: a myth in the making?