Subscribe to ShahidulNews

By Rahnuma Ahmed

It’s all about attacking Iran!

Of course, attacking Afghanistan is wrong and we should all condemn it but burkas are equally bad because they oppress women. Progressive writers should not support one in order to condemn the other. The burka is a symbol of growing religious fundamentalism and as no religion whether Islam, Christianity or Hinduism can ever liberate women, all religions must be opposed. It’s not a question of women’s choice or freedom. Surely by writing what you do, you don’t mean to say you support the burka? Shame on you!

How does one respond to such comments? Well, for starters, I’d like to state that European women who insist on wearing the burka, or their fathers, brothers, husbands, boyfriends or whoever force them to do so, will be facing legal consequences for their defiance. They are expected to abide by the `law’ of the land, regardless of whether it is just or unjust. But surely, their crime of wearing, or forcing someone else to wear, clothing `symbolic’ of oppression is not in any manner comparable to the actions of western world leaders, Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, Powell, Blair and Europe’s other leaders, who are guilty of breaching international law? Surely, the consequences of the actions of these world leaders?cluster bombs, depleted uranium, drone killings, fabricated WMDs, millions dead, thousands maimed, the birth of deformed babies, spread of cancer, greater numbers of women forced to turn to prostitution, lives ruined, homes wrecked, millions out of work?are more grave? Are oppressive actions which determine the conditions under which large numbers of people may be allowed to live, or die, to prosper, or perish.

Twentieth century’s religious wars?and by that I mean wars fought in the names of gods/deities/supreme beings?have killed far less people than have those which were waged for expressedly non-religious purposes (to maintain or overthrow colonial rule, ethnic cleansing, nationalism, imperial wars etc.) whether conducted by capitalist, communist or third world states. If you don’t believe me, just try and tally the figures. Of course, this doesn’t mean I am arguing that deaths caused by religious wars are preferable to those caused by non-religious ones.

Only some religious gods threaten to destroy humanity; their followers believe this threat to be real unlike non-believers who doubt the existence of god per se and hence have no reason to fear his malevolence. But some modern states?USA, Britain, France, China and the Soviet Union?have between them thousands of nuclear weapons, which are capable of destroying the planet a hundred times over; it would eliminate both believers and non-believers alike. The killing power of the military-industrial complex (re-named MISM, the military-industrial-security-media complex) which controls the US, reigns supreme; on its own, the US accounts for almost half the world’s military spending (46.5%).

Does not war stand in the way of women’s liberation since women have always borne the brunt of violence perpetrated by war? Are wars that are waged to save women, whether Muslim or not, cloaked as part of the west’s `civilising’ mission justified? Malalai Joya, like most Afghan women, doesn’t think so. Their problem is US-led occupation and the forces that it fosters; the US government and its allies, she says, consistently marginalise progressive and democratic movements because these are likely to mobilise Afghan people against occupation forces.

The West is secular?church and state are separate?and surely, this means that it stands for the elimination of coercion, death, destruction, torture, in other words, for progress? It is difficult for us, to find any shred of truth in this assumption as the US government, the West’s unchallenged leader, has consistently supported whichever government serves its interests, religious (Saudia Arabia) or non-religious (the Shah of Iran), regardless of how fascistic it is (for instance, Hosni Mubarak has been the president of Egypt for the last 29 years, ruling by means of a state of emergency). And, as Joya reminds us, it is the US, which installed the Taliban regime.

But, the comment above seems to say, why can’t you keep `religion’ and `imperialism’ separate, why can’t you stick to a simple story line which says Islam prevents girls from getting schooling, forces women to cover their faces, be confined to their homes, not earn a living or marry the men of their choice etc., etc. Why must you drag in all these other issues, geo-political strategies, divide-and-rule, imperial interests, oil, the new world order, US hegemony, war crimes…You mean, live in a fool’s paradise?

Many bloggers and commentators, including westerners, can see through official propaganda; they raise questions about eurocentricism, how “abstract” formulations of self and body, embedded in European political philosophy, have little bearing on Arab women’s own notions, how western ideas of freedom and liberation are equally cultural. I provide a smattering:

– But first, there are Muslim women who do choose to wear the burqa or niqab under their own volition. And second, and particularly given that fact, I do not see how an all-out ban on the burqa/niqab by a predominantly non-Muslim, male, white government will liberate Muslim women to make that choice for themselves.

– I live in a country where face veils are common; to the women who wear them, that’s not at all what they represent. If Westerners see some weird symbolism that isn’t inherent in it to the people who wear it, then whose fault is that? It’s not niqabi women’s problem that Westerners see some other message in them.

– Every culture has standards of which body parts are OK to show in public and which aren’t. In Western culture, the face is public. In the Arabic Peninsula culture, it’s not.

– So to us covering our faces seems weird and bad, and it’s hard to imagine that a woman would ever CHOOSE that for herself. But I would suggest that this is a failure in our imagination, not a failure in Arab culture.

– Looks like the French learned too well from the Nazis they surrendered to. How can they even think of legislating what people may wear?

– Finally, how does it affect us non-veil wearers? How many of those questioned about a ban are affected by someone wearing a burqa or niqab? We live in a multicultural society so what has their religious dress got to do with us? People are a bit ?creeped out?? The last time I checked, we didn?t have the right to not be ?creeped out? so there?s no need at all to ban one.

– The argument that SEEMS most credible (or maybe is just the most fashionable, because it allows bigotry to hide behind feminism) is the argument that the burqa is a ?symbol of women?s oppression.? For some people it might be, but that doesn?t mean it should be banned. It?s ridiculous. It would be like banning crucifixes to prevent paedophilia.

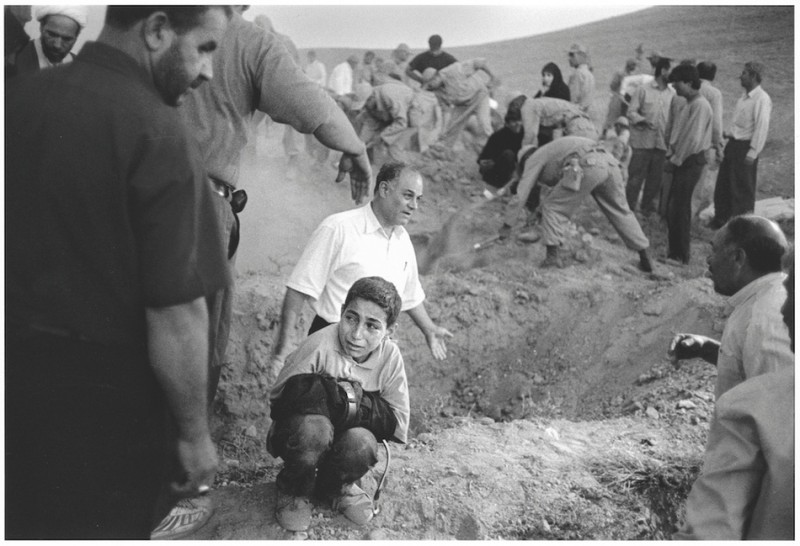

These bans remind me of The Incubator Baby Hoax which sold the First Gulf War (1990-1991) to the American public. A Kuwaiti girl claiming to be a nurse wept and told world audiences how she saw Saddam Hussein’s soldiers take babies out of their incubators, left them to die on the cold floor. ?Only to be discovered later that she was the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador in Washington; the story was concocted by a PR firm, audience surveys were carried out to make the Kuwaiti ambassador more likeable (clothing, hairstyle). Research undertaken had revealed that American people would be convinced if Saddam Hussein was portrayed as “a madman who had committed atrocities even against his own people, and had tremendous power to do further damage, and he needed to be stopped.” Less than a decade later, videos of Taliban beheading of a woman to cheering crowds spread virally, it helped to garner support for the Afghan invasion.

As the burka ban gains momentum, I hear the beating of war drums. So, I wonder, whose next?

Is Orientalism over? Those who criticise my position, if at all bothered by this question, would seem to think so. But scholars argue that contemporary representations of Islam and Muslims across a wide range of social/political discourses including journalism, other mass-communicated media as well as academic research, is modern Orientalism. It impoverishes the rich diversity of Islam, it caricatures Islam. Orientalism is not a mere “mental phenomenon,” to view it thus sidelines its practical implications. It attempts to restore practices that ensure inequitable social systems of power, and behavioral manifestations such as discrimination, physical attack, extermination (John E. Richardson, MisRepresenting Islam, 2004). Stereotypes of Islam that exist in historic Orientalist writings of the 13th century by Christian polemicists recur in contemporary writings: sex, violence, cunning and the irrationality of Islam. But although the topics are constant, the argumentative position has shifted with changes in Western cultural values. When Western polite society found sex to be immoral, or at the very least something to be endured, Orientalists accused Islam of promoting and celebrating such licentious activity. But now that polite society valorises gender and sexual equality, neo-Orientalists argue that Islam promotes, at times, demands, the opposite.

I refuse to live in a fool’s paradise given current speculation (intelligent, well-researched) that several US nuclear bombs which went “missing” for 36 hours (2007) may be connected to US plans to nuke Iran. Given plans of setting up the regional counter-terrorism centre in Dhaka, second to the one in Indonesia (a US client state) . Who’s to guarantee that Bangladesh will not attract the attention of militants? What is happening? Are we deliberately being sucked into the US war on terror, about to become yet another battleground?

Let history not judge us as collaborators, or too stupid to look beyond their nose.

.