The Daily Star

Volume 4 Number 25

Sat. June 21, 2003

Literature

Travel Writing

Juggling, juggling, juggling…

Shahidul Alam

And while last week Fakrul Alam went on vacation to Indonesia, this week another, and very different, Bangladeshi (a photographer/gearhead in loosekurtapyjamas) flings himself headlong into Singapore to arrange a photography exhibition. With very different results.

I was getting closer to my usual time of arriving forty minutes before departure. The Singapore Airline guy had warned me to arrive three hours early. "The new computers…" he went on. I assured him I had flown several times since the new computers had been introduced at Zia. I had been there on day one, when these glistening new machines had led to long queues as confused immigration officers tapped in a letter at a time and constantly consulted more computer-savvy colleagues about the entry of some insignificant data.

Usually it was the migrant workers who were on the defensive, being made to feel worthless as they struggled with immigration forms. The roles had now been reversed. The workers seemed to enjoy waiting in line while their tormentors fumed in silence at the wonders of technology.

The flight was uneventful, except for the problems of trying to find a safe parking place for my six-foot print. Eventually the air hostess took my print away, leaving me nervously peering through the alleyway hoping she didn't fold it up to fit the container!

As we disembarked, we were greeted by another marvel of science. Another queue developed as the infrared cameras, revealed your body warmth. Posterised colours showed the relative warmth of every part of your upper anatomy as you walked by. It was live television!

It took people a while to work out who those people with strange colours were, but once it dawned, then it was movie time. Many years ago, on a cold day in London, I had noticed the coldness of the tip of my nose, and the near frost on my beard. I had always been curious about how the hairs on my chest would appear in infra red which the Singapore climate was far more suitable for observing.

Lance and Gim Lay ambled in. Gim Lay was a gallery official and had to make an appearance for her visiting artist, so she didn't have a choice, but I felt sorry for Lance, having to wake up at the ridiculous hours that Singapore Airlines arrives at, just because he's a friend.

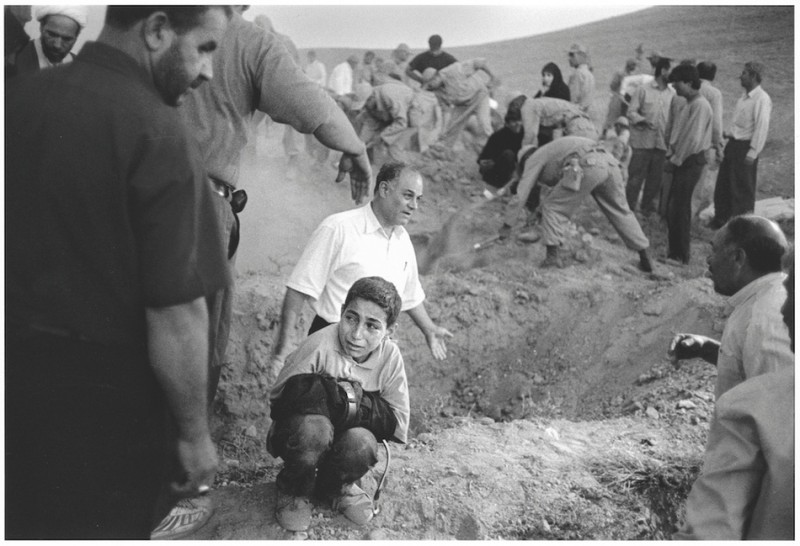

After a very short pit stop at Teek's spacious studio, it was down to the gallery of the Singapore History Museum. We had agreed to give the show a 'raw' look. So construction scaffolding, helmets, sandbags, bricks, warning tape and cones had all been set up. Canvas strips hung on the scaffolding were to be our exhibition panels. By now I had been nearly eight hours without Internet and was getting withdrawal symptoms. Lance hurriedly inserted the appropriate IP numbers and I was online. Singaporean broadband was considerably different from Dhaka 'broadband' and I quickly went through my backlog of mail. Most of it was junk of course. After deleting the 101 tips for enlarging my privates, making 50,000 dollars a week offers plus the few Nigerian scams, I settled down to the urgent mail. Deadlines were looming. Salgado's images needed to be sourced, the workshop in Prague needed to be settled, and there were Pathshala exam sheets to be marked! I tried to get as much done using the museum connection. Even with these fast speeds, paying 15 Taka a minute at the hotel, took a bit of getting used to. The 15 Taka an hour Dhaka cyber cafés didn't seem so bad after all!

An army of volunteers had arrived, and I was expected to direct them about the setting up of the exhibition. It is difficult to appear intelligent when a horde of excited youngsters wait for each word to drop, especially when you don't have a clue as to where you are going. Still, the experience of having done this many times before did help, and with my eager volunteers, we were slowly getting the exhibition in shape. Gim Lin stormed in and out, pressing a row of panic buttons. The mounters were having problems with the inkjet prints. The precise positioning of my large prints needed my immediate attention. The television interview needed to be scheduled in, and what could I not eat?

Meanwhile I had other concerns. I had been surreptiously relieved of my Nokia Communicator the week before in a tram in Brussels, and being the techie freak that I was, not having a PDA phone was almost as bad as not being online 24 hours. So friends had been mobilised to research the PDA phone scene. What was available, where could we get it, who would give the best discount and who was going to accompany me to ensure I didn't get ripped off. I also needed a local person who would get the account on my behalf, as the phone company needed a local address.

Meanwhile Chor Lin, the director of the museum, came in for a courtesy visit. Her husband Peter Schoppert had masterminded the "Day in the Life of" series books for the Asean region, and we had many common friends. Raghu Rai in particular had been a frequent visitor while his books were being printed in Singapore. The technicians interjected in between: What did I need for my presentation? What program was I going to use? It all seemed so serious!

I managed to ring Justin. The last time we had met was when he had come over to Pathshala with David Wells for the workshop that led the lead story on Aramco magazine. Since then I had seen his Dhaka pictures in Time magazine, and I remember that ex-minister Abdul Mannan, during an earlier flight to Dhaka from Kuala Lumpur, had waxed lyrical on his slide show on Bangladesh. Justin was off the next morning to Shanghai, so that night was our only chance to meet. Eddie dropped me there and after a few mobile calls (how did we manage in the Dark Ages before mobiles?) Justin appeared at the other end of the park and directed us to the flat. The flat was a spacious house in Newton Circus and couldn't have been more ideally placed. Kaychin, Darren and Nick appeared bringing along P and P, who had set up the new photographic school Objectives and we all went to the food stalls. The food at Newton Circus was always nice and Justin knew where the best sting ray, guava juice and satay were to be found. Leaving Justin to pack for Shanghai, we went back to the museum, where I showed Darren the Chobi Mela II catalogue. They had been there throughout the circus that we had with customs and hadn't had a chance to see the shows that the customs had blocked, so the catalogue was the first chance they had to see the Malaysia and Salgado shows. We trundled home at around 3 a.m. to Tuck's Geylang Road studio, ready to drop.

The next morning the museum had geared up for action and every visitor was being asked to fill in a SARS form. Had you had any fever? Which countries had you visited. Any other symptoms? Who should we contact in case of trouble? A big A4 sheet every day for all gallery staff and visitors. More awaited. Chor Lin took us out for dinner in the evening, and the other speakers and the moderator were all there. As we walked towards the entrance of the restaurant and riverside point, a woman approached us with a thermometer in hand. Held rapier like, this tiny but evil looking device was clearly something she would relish inserting into some unsuspecting orifice. Gingerly we suggested we would sit outside in the patio. We didn't really need the airconditioned interiors and we were not going to have the buffet anyway. They agreed to make room for us by the river bank, but the rapier had not been sheathed. Gloved fingers tugged at my ear as it was brutally inserted inside. Chor Lin was delighted. This was a photo op! Being a photographer I could hardly say no. I was the only one with a camera, so I had to face the indignity of having my own camera used for immortalising on celluloid my ear-pulling session. The photographer was fussy. We had to stand in front of the aquarium, and crouch a bit so he would have the right composition. Not too much movement, as it was a slow shutter speed, and could the tester crouch too? At least my mother had not raised me for nothing. My one offering to humanity could be the pleasure I had given to so many Singaporeans as they chuckled to this spectacle. Oh how I waited for their turn!

It was refreshing to see so many photographers working into the early hours, as we mounted, trimmed, adjusted, hung the photographs. It reminded me of the early days of the Bangladesh Photographic Society. It felt so long ago.

Thursday was the big day. The opening was in the afternoon, and we still had plenty to do. Sandwiched between interviews, captions, a final edit and lighting adjustments took up most of the next day. Still no PDA phone. What was I going to do? Eddie suggested secondhand phones. Singaporeans apparently change phones every 2-3 months. A six-month-old phone was passé. So we should have been able to find a very good deal on a decent six-month-old set. The press had done their job, and friends whom I hadn't been able to contact, came over as they had seen me on TV. I had to sneak off to the computer several times as MC was breathing down my neck: were my exam papers marked yet? Some of the photographers had brought in their portfolios in between. Would I have time to review them please? It was going to be another long night. The next morning Nick and I went for a recce to Bugis. The salesman was quick to spot the techie freak and impressed me with the virtues of the operating system of the OX2. The Nokia and the Ericsson didn't stand a chance, and he was going to give me a special deal! I did have the judgement to take the time to consult my friends, and do some further research. Ed had mentioned scouting the Saturday papers where the best deals were to be found. But the salesman had done his job, and I was well and truly hooked.

Choy had asked us to arrive early to the auditorium to plan the presentation, and I arrived a bit late: There had been so many phones on offer at Bugis!

But everything went fine, all according to plan. And on the plane back home, I slept the sleep of the dead.

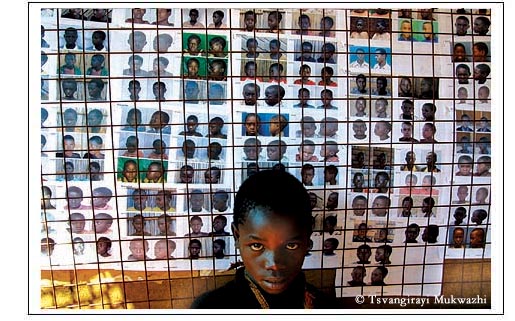

Shahidul Alam heads Drik Picture Gallery in Dhaka.