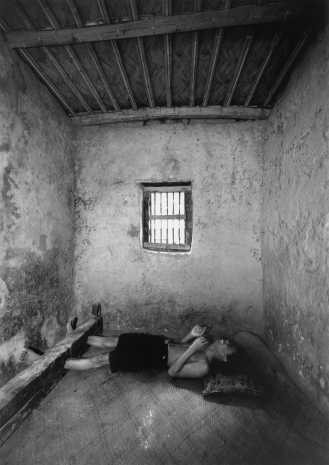

Dr A.K.M. Abdus Samad, the director of the mental hospital in Hemayetpur, Pabna, was pragmatic. “An average of 2% of all populations are schizophrenic, and of course there are many other mental ailments. In this country of 130 million, we have one hospital with 400 beds. What do you expect? The government allocation for food is 18 Taka per day (about 45 US cents when we met in 1993). Many mental patients are hyperactive and need more food. A good portion of that 18 Taka goes to the contractor, the remainder has to provide three meals a day. So what can I do? I make sure they get plenty of rice. That way they at least have a full stomach. We have little money for drugs, and virtually no staff for counselling, so we keep them doped. Then they don’t suffer as much.”

The other doctors had a different take. “Pity you’ve come on a Friday they said. On a weekday we could have shown you an electric shock treatment.” It seemed to be a popular ‘treatment’. To the uninitiated like me, the violent convulsions and the near comatose state the patients lay in afterwards didn’t seem to be the way to treat anyone. The care givers differed. The treatment was generally given to suicidal patients they said, and the way they saw it, it was “better than letting them kill themselves.” I didn’t have much of an argument against that one.

I saw the group of visitors come round to the dorms at night and peep through the windows. It was well after visiting hours, but they had paid to get in and have a look at the ‘pagols’ (loonies). On Eid day, many would dress up and come to the peep show. Some patients did get visitors on Eid, a select few even got new clothes or special food, but for most, it was another day of waiting. Another day of hoping that someone close might come and take them away.

In every ward I went, someone would take me aside, and slip a note in my hand. Invariably, scrawled in that note would be an address. “You must take it to them (their relatives). Tell them I’m OK. Tell them to take me away from here.” The first few times I did try and contact those relatives. Some addresses had people who recognised them, most didn’t. None seemed keen on responding. Eventually I gave up, but I would still take the notes. In Hemayetpur, even false hope seemed something worth giving.

—————————-

As another Eid approaches, I remember the child Shoeb Faruquee had photographed in Chittagong. It won him an award at World Press Photo, but I wonder where the child is now.

Patient at mental hospital, Bangladesh

? Shoeb Faruquee, Bangladesh, Drik/Majority World

Mohammad Moinuddin had yet another story to tell:

http://www.newint.org/columns/exposure/2006/08/01/md-main-uddin/

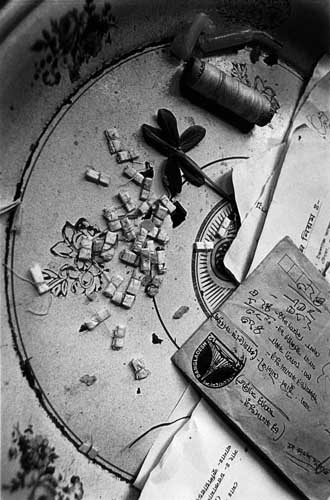

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh, Drik/Majority World

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh, Drik/Majority World

I was on an assignment at Domra Kanda, an asylum for the mentally ill in Kishoreganj, Bangladesh, where the only medications provided are these ?medallions? filled with spiritual spells and ?blessed water? from traditional spiritual healers. Illiteracy about medical treatments ? particularly those related to mental health issues ? misconceptions and limited health facilities mean that many parents resort to their faith in such medallions and other blessings from spiritual healers. The clinics which provide such traditional solutions do not offer scientific medications of any type and neither are they approved by any health authority. But for many Bangladeshis, faith in traditional healers and their treatments is more powerful, effective and easily available than scientific medication. The parents strongly believe that it is their faith in such spirituality that will cure their child and bring back the long lost peace and happiness to their family.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

In a world where normality is a virtue, I salute the few individuals who have chosen to be different.

Shahidul Alam

23rd October 2006. Dhaka

ps: Apologies to ZAK on my spelling of Eid: http://www.kidvai.com/zak/2005/11/its-that-time-of-year-again.html

Category: Human rights

Profits versus the Poor

?I have lost a son, maybe I?ll lose another, but I won?t let them setup a coalmine here.? To Tahmina Begum who had lost her son Toriqul to police bullets, her land was also her family.

?I have lost a son, maybe I?ll lose another, but I won?t let them setup a coalmine here.? To Tahmina Begum who had lost her son Toriqul to police bullets, her land was also her family.  It could have been a ?B? rated western except that it is set in the east.

It could have been a ?B? rated western except that it is set in the east.  People wanting to hang on to their ancestral land versus mining companies wanting huge profits. There have been only minor changes from previous scripts. When farmers wanted fertilizers and seeds, the police had opened fire killing them, when they wanted electricity to irrigate their soil, the police had opened

People wanting to hang on to their ancestral land versus mining companies wanting huge profits. There have been only minor changes from previous scripts. When farmers wanted fertilizers and seeds, the police had opened fire killing them, when they wanted electricity to irrigate their soil, the police had opened  fire killing them. Now that they want to retain their land rather than have it converted into coal mines again the police have opened fire killing them.

fire killing them. Now that they want to retain their land rather than have it converted into coal mines again the police have opened fire killing them.  The Shaotals, being indigenous minority groups, find themselves even more vulnerable within this persecuted community. In the shootings on the 26th September 2006, in Phulbari, Dinajpur, in northwestern Bangladesh, at least six villagers are known to have been killed, over a hundred are said to be missing.

The Shaotals, being indigenous minority groups, find themselves even more vulnerable within this persecuted community. In the shootings on the 26th September 2006, in Phulbari, Dinajpur, in northwestern Bangladesh, at least six villagers are known to have been killed, over a hundred are said to be missing.

I hear the screams

![]()

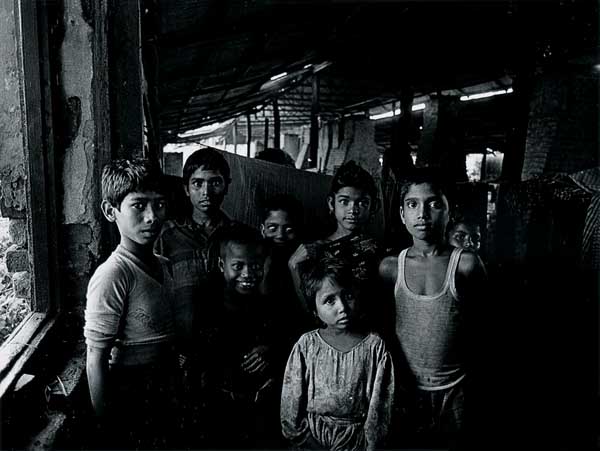

Even after years of playing Pied Piper with a camera, I am still taken aback by children insisting on being photographed. It was September 1988, and we had had the worst floods in a century. These people at Gaforgaon hadn’t eaten for three days. A torn saree strung across the beams of an abandoned warehouse created the only semblance of a shelter. Their homes had been washed away. Family members had died. Yet the children had surrounded me. They wanted a picture.

It was dark in that damp deserted warehouse, but the broken walls let in wonderful monsoon light, and they jostled for position near the opening. It was as I was pressing the shutter that I realised that the boy in the middle was blind. He had pushed himself into the centre, and though he wasn’t tall he stood straight with a beaming smile.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CARE

Clip on story of the blind child, from keynote presentation on citizen journalism at 50th Anniversary of World Press Photo in Amsterdam.

I’ve never seen the boy again, and today I question the fact that I do not know his name. But he has never left my thoughts and often I have wondered why it was so important for that blind boy to be photographed.

It’s happened elsewhere, in boat crossings at the river bank. In paddy fields heavy with grain, in busy market places. A shangbadik (literally a journalist, but in practice any person with a half decent camera) was hugely in demand. They refused to take the fare from me at the ferry ghat. Opened up their hearts and told me their most personal stories. Confided their secrets, shared their hopes. Never having deserved such treatment it has taken a while for me the photographer, to work out why being photographed meant so much to that blind child.

The stakeholders of Bangladeshi newspapers are the urban elite. Consequently stories from the village are about the exotic and the grotesque. Village people exist only as numbers, generally when plagued by some disaster and only when figures are substantial. A photograph in a newspaper, regardless of how token the gesture, is the only time a villager exists as a person. A picture on a printed page would have lifted that blind boy from his anonymity. That humbling thought stays with me whenever I am feted as a shangbadik in some small village. I receive their gift of trust gently, careful not to break the delicate contents.

It was as a photographer of children that I had begun my career. It was way before 9/11 and one could make appointments with strangers and go to their homes. I took happy pictures of kids, and parents loved them. It was easy money, except when I would photograph the children of poor parents. They loved the pictures but couldn’t afford to pay, so I would quietly leave the pictures behind and pay the studio out of my pocket. Back in Bangladesh, the only way I could make money was as a corporate photographer, but something else was happening. We were in the streets, trying to bring down a general who had usurped power. I didn’t know it then, but I was becoming a documentary photographer. Suddenly taking pictures of children meant more than smiling kids on sheepskin rugs.

As the pressure against the general mounted, I photographed children who joined the processions. The night he stepped down, I photographed a little girl with a bouquet of flowers. She was out with her dad in the middle of the night, celebrating the advent of democracy.

I am back in Kashmir eight months after I had been here photographing the advent of winter. The valleys of this fertile land are green with new crops,

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

but many of the homes are still to be rebuilt. As I walked through the rubble, the kids again wanted to be photographed.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Najma came running, her bright red dress popping out of the green maize fields.Unsure at first, she smiled when I told her she had the same name as my sister.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Zaheera, a cute girl with freckles, gathered her friends and sang me nursery songs. But my thoughts are far away. Despite the laughter and the nursery songs very different sounds enter my consciousness. I remember the children screaming on the night of the 25th March 1971, when I watched in helpless anger as the Pakistani soldiers shot the children trying to escape their flame throwers. The US had sent their seventh fleet to the Bay of Bengal, in support of the genocide. Today, as I remember the Palestinians and the Lebanese that the world is knowingly ignoring, I can hear the bombs raining down on Halba, El Hermel, Tripoli, Baalbeck, Batroun, Jbeil, Jounieh, Zahelh, Beirut, Rachaiya, Saida, Hasbaiya, Nabatiyeh, Marjaayoun,Tyr, Jbeil, Bint Chiyah, Ghaziyeh and Ansar and I hear the screams of the children. Piercing, wailing, angry, helpless, frightened screams.

News filters through of the children killed in the latest bombing. The photographs have kept coming in, horrific, sad, and disturbing. Mutilated bodies, dismembered children, people charred to ashes. But none as vulgar as those of Israeli children signing the rockets. Death warrants for children they’ve never known.

I remember my blind boy in Gaforgaon. The Lebanese and the Palestenians are also people without names. Their pain does not count. Their misery irrelevant, their anger ignored. Sitting in far away lands, immersed in rhetoric of their choosing, conjuring phantom fears necessary to keep them in power, hypocritical superpowers fail to acknowledge the evil of occupation. The ‘measured response’ to a people’s struggle for freedom will never in their reckoning allow a Lebanese or a Palestinian to be a person.

When greed becomes the only determining factor in world politics. When the demand for power, and oil and land overshadows the need for other people’s survival, I wonder if those screams can be heard. I wonder if those Israeli children will grow up remembering their siblings they condemned. I wonder if through all those screams the war mongers will still be asking “why do they hate us”?

11th August

Siran Valley, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

So Jamila could be Happy

![]()

Khala (auntie) was happy to see me. It was on impulse that I had gone to see her that day. I hadn’t seen her for a while and simply wanted to know how she was. She greeted me with her usual impish smile, but the smile had more to do with the fact that she had found a photographer in the house. Quickly she bundled me to the next room where a woman was holding a new born baby. Jamila had just been born, and Khala had found a photographer who could record this important moment.

The mother was quiet, and after a few photographs, I left mother and daughter in peace. This was a child the mother knew she couldn’t afford to keep. It was back in the drawing room of that old Dhanmondi house that I saw Nasreen. She had come in through the garden, one of the few in Dhanmondi that the developers had not yet buried in concrete. We’d known each other for a long time, and along with her sister Shireen, had attended many rallies organised by Nari Pokkho, the womens group that they belonged to. On many a protest, I had become an honorary woman and a proud member of the group.

Her wild curly hair bouncing as she spoke, we talked of the work we were doing together on HIV/AIDS. Positive Lives, an exhibition I had worked on as a curator and a photographer, was a show Action Aid had been touring country wide. They had organised educational programmes and gotten local celebrities to draw the crowds in. It had been a hugely successful tour. We talked of the work they were doing with the acid survivors. Rattling off ideas at great speed, for me to pursue, she dashed back to the office. Breezing out as she had breezed in. It was later that I learned that Nasreen and her husband Choton, had adopted Jamila. From then on, it was Jamila who took centre stage in Nasreen’s life. But that was the last I saw Nasreen alive.

Choton and I were fellow journalists, and whenever an important statement needed to go to press, it was Choton I would turn to. From Press Club to Motijheel to Topkhana, we would do the night time beat. He knew every editor in town and which desk to leave the press release on. Sometimes it was in search of Choton, that I would call up Nasreen. We would talk of work, but invariably the conversation veered to Jamila, never accidentally.

When I heard of the accident, I hadn’t been too concerned. A leg injury inside the parking space didn’t sound too critical. But soon I sensed something was seriously wrong. All day long people gathered at the hospital. Ministers, celebrities, acid victims, friends, ordinary people. It was through their faces that I learnt how Nasreen had touched people’s lives. It was in their tears that I found how much love she had given. Some whispered in disbelief, some wailed out loud. Choton, Shireen and Zafrulla were distraught. Khala had not yet been told. Naila was like a rock. It was she who had to break the news. She knew Nasreen the fighter, was not going to win this one. Torn up inside, Naila kept calm. As I watched inside ICU 1, I could see our fighter losing the one fight she had never prepared herself for.

Reading her obituary in the Guardian today, I remembered that it was in the same ICU where we had kept vigil when Rashed Khan Menon had been shot. I had photographed another fighter Jahanara Imam, who had been waiting outside with us. Years later, Rashed Bhai had recovered, but I had written Jahanara Khala?s obituary in the Guardian. Police brutality and cancer had taken their toll. That day I had sat with Rahnuma next to where Khala had waited and quietly held hands. It rained, as it had done when my father died and for all the deaths I could remember.

Back in Dhanmondi, Friends had arrived from far away lands. People had come from the villages. We all stood in disbelief. As I walked out of that room heavy with sadness, I heard peels of laughter from the garden. Jamila, not sure of why her mother was not there, or why there were so many people, was playing with her friends.

Her mother was called ‘Happy’ by her friends. At her funeral in Ghazipur, Happy’s friends sang songs of remembrance. They spoke of her courage and her ability to love. They spoke of her tenacity. I thought of Jamila and remembered how Happy had changed the lives of so many others, and felt it was through Jamila’s laughter that Happy should be remembered.

Shahidul Alam

1st May 2006. Dhaka

The Poverty Line

![]()

Revolution ? Pablo Bartholomew

The Poverty Line

Tarapodo Rai

I was poor. Very poor.

There was no food to quell my hunger

No clothes to hide the shame of my naked body

No roof above my head.

You were so kind.

You came and you said

‘No. Poverty is a debasing word. It dehumanizes man.

You are needy.’

My days were spent in dire need.

My needy days, day after day, were never-ending.

As I grew weaker

Again you came.

This time you said.

‘Look, I’ve thought it over,

“Needy” is not a good word either.

You are destitute.’

My days and my nights, like a deep longing sigh,

Bore my destitution.

Cowering in the burning heat,

Shivering in the cold winter nights,

Drenched in the never-ending rains.

I went from being destitute to greater destitution.

But you were tireless.

Again you came.

This time you said

‘There is no meaning to this destitution.

Why should you be destitute?

You have always been denied.

You are deprived, the ever deprived.’

There was no end to my deprivation.

In hunger and in want, year after year,

Sleeping in the open streets under the relentless sky

My body a mere skeleton

Was barely alive.

But you didn’t forget me.

This time you came with raised fist

In your booming voice, you called out to me.

Rise, rise the exploited masses.

No longer did I have the strength to rise.

In hunger and in want, my body had wasted.

My ribs heaved with every breath.

Your vigour and your passion

Were too much for me to match.

Since then many more days have gone.

You are now more wise, more astute.

This time you brought a blackboard.

Chalk in hand, you drew this glistening bright long line.

This time you had really taken great pain.

Wiping the sweat from your brow, you beckoned me.

‘Look. See this line.

Below, far below this line, is where you belong.’

Wonderful!

Profusely, Gratefully, Indebtedly, I thank you.

For my poverty, I thank you.

For my need, I thank you.

For my destitution, I thank you.

For my deprivation, I thank you.

For my exploitedness, I thank you.

And most of all, for that sparkling line.

For that glittering gift.

O great benefactor!

I thank you.

Translated from Bangla by Shahidul Alam.

Where Elbows Do The Talking

![]()

It was a mixed week. Sandwiched in between the hartals and the ekushey

barefoot walks and the launch disaster, were news items that led to very

different emotions at Drik. Shoeb Faruquee, the photographer from Chittagong, won the 2nd prize in the Contemporary Issues, Singles,

category of the world’s premier photojournalism contest World Press

Photo. The photograph of the mental patient locked by the legs as in a

medieval stock, is a haunting image that is sure to shake the viewer.

However, the stark black and white image tells a story that is far from

black and white. In a nation with limited resources, medical care for

all is far from reality. Expensive western treatment is beyond the reach

of most, and has often been shown to be flawed. Alternative forms of

treatment is the choice of many. The fact that the boy photographed was

said to have been healed, further complicates the reading of this image.

Shoeb is one of many majority world photographers who have attempted to

understand the complexities of their cultures, which rarely offer

simplistic readings.

It was later in the week, that Azizur Rahim Peu, told me that the

affable contributor to Drik, Mufty Munir, had died after a short illness

at the Holy Family Hospital. I would contact Mufty when I was in

trouble, needing to send pictures to Time, Newsweek or some other

publication. We would work into the night at the AFP bureau, utilising

the time difference, to ensure the pictures made it to the picture desk

in the morning. Occasionally, while hanging out at the Press Club

waiting for breaking news, we would dash off together. Mufty

uncomfortably perched on the back of my bicycle and me puffing away

trying to get to the scene in time.

Wire photography is about speed, and their photographers are known for

being pushy, but this shy, quiet, self effacing photographer made his

way to the top through the quality of his images. We had to push him to

have his first show in 1995, which our photography coordinator Gilles

Saussier and I curated. The show at the Alliance was a huge success, but

Mufty was not impressed by the excitement the show had created. He

simply wanted to get on with his work.

He did have problems with authority, or rather, authority had problems

with him. Despite his shyness, he was a straight talking photographer,

who didn’t hesitate to protest when things weren’t right. Not being the

subservient minion the gatekeepers of our media are accustomed to, he

often got into trouble. But the clarity of his protests played an

important role in establishing photographers’ rights. In the abrasive

world of press photography, where elbows do much of the talking, this

gentle talented practitioner will be dearly missed.

Unknown to the rest of us, the brother of Rob, the gardener at Drik,

died in the launch that sank in the storm at the weekend.

I Will Not

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Today on Earth Day we are celebrating by making promises

But I will not

I will not stop throwing paper on the ground.

I will not stop using plastic bags

I will not go to clean the beaches

I will not stop polluting

I will not do all these things because I am not polluting the world

It is the grown-ups who are dropping bombs

It is the grown-ups who have to stop

One bomb destroys more than all the paper & plastic that I can throw in all my life

It is the grown-ups who should get together and talk to each other

They should solve problems and stop fighting and stop wars

They are making acid rain and a hole in the ozone layer

I will not listen to the grown-ups!

[Student of class five of Karachi High School on Earth Day 1991].

It was in the wee hours of the morning. Propped up in our beanbags Nuzhat and I chatted while Zaheer and Ragni clicked away on their keyboards. I was in Karachi doing a story on Abdul Sattar Edhi, the philanthropist I admired greatly. Nuzhat and I had a lot of catching up to do, and our stories wandered in unplanned directions. We talked of when she and Nafisa Hoodbhoy had started the Peace Committee in Karachi and as she remembered this story her bright eyes welled up. Nuzhat was not the sort of person one could imagine being angry. But as she recalled the words of this little boy, she shook with emotion.

It was a week after they had heard the news of the US dropping a bomb every two minutes on Iraq. They had talked in school of how the world was being destroyed, of how the minds of people were being moulded, of how Pakistanis were looked upon at airports, but how the work of Edhi went unreported. She recalled how at the end of her talk, the chief guest, a woman known for her good work, went up to the boy and quietly told him off. How the prizes went to the other kids who had made presentations that no one could remember.

What can we say to the blind & deaf?

What does education & learning mean?

What should we teach & why do we teach it?

These were questions Nuzhat asked that night. Questions we continue to ask.

As we put together the work for this festival, I have marvelled at the range of statements the artists have made to address ?resistance?. At their modes of expression. At their defiance. To resist, to challenge, to question, to go against the grain, to deliberately choose the untrodden path is a conscious decision. It is a risky route fraught with danger, but a route we must follow, if change is to come.

The festival itself continues to buck the trend. Open air marquees without gates or walls bring rarely seen work to a wider public. Billboards on cycle rickshaws take exhibitions to city spaces that have never known gallery walls. Combining innovative low cost solutions with state of the art technology, video conferences link the virtual with the real, while canvas prints on giant scaffolding scorn the air conditioned confines of exclusive openings. Hand tinted prints rub shoulders with pica droplets on digital media. Fine art, conceptual work, installations, traditional photojournalism, coexist in a strange mix, oblivious to attempts to categorise and label. The future, the present and the past huddle, sometimes uncomfortably, to produce a kaleidoscope of images and woven messages, that question, reflect and celebrate aspects of our existence.

When globalisation has become a euphemism for westernisation, it is this dissolution of borders, this resistance to consumerism, this dream of a world where the might of a few, can be effectively challenged, this belief that tanks and stealth aircraft, and media spin will not subdue an indomitable spirit, that characterises this festival. It is this attempt to subvert, through blogs and handbills and word of mouth, the propaganda machineries that dominate the airwaves, that the artists have taken as their inspiration. The festival is a call to resist, and a declaration of the resistance to come.

Shahidul Alam

5th December 2004

From Seventh Fleet to Seventh Cavalry

25th March 1971. My eldest niece had just been born the day before. It was a premature birth. Amma had found a Mariam flower and the flower had bloomed, heralding the birth. She had stayed behind at the clinic. We had felt something was afoot, and Babu Bhai and I went out to try and get mother and child back from Dr. Firoza Begum’s clinic in Dhanmondi. Our home might not have been safer, but at least we’d be together. Friends were building roadblocks in the streets by then, and let us through reluctantly, warning us that we had little time.

We went along the narrow road by Ramna Police station to Wireless Mor, it being too dangerous to go along the main road. I climbed over the barbed wires on the boundary walls to get to my sister’s flat, but my brother in law felt it was too dangerous to go out, so I turned back. By then the tanks were on the streets.

I had fallen asleep, but woke up to the sound of gunfire. The wide red arcs of tracer bullets had lit up the sky. The only tall building nearby was the Hotel Intercontinental, where the meetings between Mujib and Bhutto had taken place, and where the foreign journalists were staying. The slum next to the Sakura Hotel and the nearby\ newspaper office were ablaze. We could hear the screams. Those who were able to escape the fire, ran into the machine gun fire waiting outside.

Abba (my father), Babu Bhai and I watched in silence. We had argued with Abba about Pakistan, but he had been victimised as a Muslim in pre-partition India, and would not support what he saw as the break up of the nation. That night he finally broke our silence by saying, “now there is no going back.”

We heard the gunshots all night, and there was a curfew the following day. Eventually when there was a small break in the curfew the day after, Abba went to get supplies, and Babu Bhai and I got my sister and her daughter to Nasheman, in Eskaton where we lived. We called her Mukti, meaning `freedom’. But relatives warned us that it was too dangerous to use that name, even if it was a nick name to be used only amongst ourselves. So Mukti became Mowli, and even after independence, the name stuck.

Twenty five years later in 1996, I tried to put together a collection of images of ’71 for our 1996 calendar. I am reminded of the introduction:

[Twenty five year ago, even longer perhaps, just a camera in hand, they had gone out to bring back a fragment of living history. Today, those photographs join them in protest. Peering through the crisp pages of the newly printed history books, they remind us, “No, that wasn’t the way it was. I know. I bear witness.”

The black and white 120 negatives, carefully wrapped in flimsy polythene, stashed away in a damp gamcha, have almost faded. The emulsion eaten away by fungus, scratched a hundred times in their tortuous journey, yellowed with age, bear little resemblance to the shiny negatives in the modern archives of big name agencies. They too are war weary, bloodied in battle.

So many have sweet talked these negatives away. The government, the intellectuals, the publishers, so many. Some never came back. No one offered a sheet of black and white paper in return. Few gave credits. The ones who risked their lives to preserve the memories of our language movement, have never been remembered in the awards given on the 21st February, language day.

25 years ago, they fought for freedom. They didn’t all carry guns, some made bread, some gave shelter, some took photographs. This is just to remind us, that this Bangladesh belongs to them all.]

Drik Calendar 1996

Today, embedded photojournalists with digital cameras, give us images of yet another aggression. This time, from the other side of the gun. The 50 clause contract that gives them access to imperial military units, like the unwritten rules that allow them access to presidential pools, ensure that `free’ media remains loyal to the warmongers. Will we ever get to see the images taken by the Iraqi photographers? Will their negatives die the same death? Will those images, like the bombed ruins of a magnificent city, be the only tattered remains of an aggression that the world allowed to happen? In ’71, the Seventh Fleet was stationed in the Bay of Bengal. The Mukti’s were not deterred by this show of power. They won us our independence. Today, after 43 more US military interventions across the globe, it is the Seventh Cavalry that bombs Iraq. And our own government, forgetting the lessons of history, forgetting that they tried to kill our unborn nation, turns against the will of its people. Our own police turn against us in our anti war rallies, to protect the biggest aggressor in history. These negatives may not survive, but the collective memory of the people of the world will, and our children will confront us in years to come.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

26th March 2003

* A flower from Arab deserts, used during labour to predict the time of childbirth.

** A working man’s cloth of coarse cotton, used as padding when carrying weight, to carry food, and to wipe away sweat.

We Did Say No

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

My questions are many. Why is there no UN resolution against the United States, for blatantly initiating an unprovoked genocide? Whydoes not the UN Security Council, demand that the most habitual aggressor in recent history, disarm and destroy

its weapons of mass destruction? Why is it that despite our collective strength, the most we can muster is a passive condemnation of a mass murder? Whatever may happen after the bombs have dropped, we will not be able to hide our shame. It may not have been in our name, but we sat and watched. We allowed it to happen. It is a guilt that will haunt us. While I sit in anger, wondering how, despite all our rhetoric, we watched a nation being plundered, without raising a finger to stop it, this quiet reflection from Baghdad University campus brings homethe extent of our complicity. These are the people we allowed to be destroyed. Our lives will go on, and we will face another day. They will not. And we will be content because we had said no

Shahidul Alam

Mon Mar 17, 2003

===============================================================

At the College of English, it is most definitely springtime. Co-eds are chattering cheerily and they smile as we pass. "We are intent on finishing the syllabus, war or no war," says Professor Abdul Jaafar Awad. He tells us that during the Gulf War of 1991, he was discussing a doctoral dissertation with a student while American and British warplanes were bombing Baghdad. Jawad's determination to carry on despite the approach of war is shared by the students at his department.

Students at a class on Shakespeare are discussing Romeo and Juliet when we interrupt them. No, they say, they don't mind answering some questions from the Asian Peace Mission. They are carrying on with Shakespeare, but their answers show that morally they are on war footing. What do they think of George Bush? "He is like Tybalt, clumsy and ill-intentioned," says a young woman in near perfect English. What do they think about Bush's promise to liberate them? Another co-ed answers, "We've been invaded by many armies for thousands of years, and those who wanted to conquer us always said they wanted to liberate us." What if war comes, how would they feel? Another says, "We may not be physically strong, but we have faith, and that is what will beat the Americans." A young professor tells me, "I love teaching, but I will fight if the Americans come." These are not a programmed people. Saddam Hussein's portrait may be everywhere, but there are not programmed answers. In fact, we have hardly encountered any programmed responses from anybody here in the last few days. Youth and spring are a heady brew on this campus, and it is sadness that we all feel as we speed away, for some of those lives will be lost in the coming war. As one passes over one of the bridges spanning the Tigris River, one remembers the question posed by Dr. Jawad: "Why would today's most powerful industrial country wish to destroy a land that gave birth to the world's most ancient civilization?" It is a question that no one in our delegation can really answer. Control of the world's second biggest oil reserves is a convenient answer, but it is incomplete. Strategic reasons are important but also incomplete. A fundamentalism that grips the Bush clique is operative, too, but there is something more, and that is power that is in love with itself and seeking to express that deadly self-love.

An American journalist I meet at the press centre says the people are carrying on as usual because they are in deep denial of the power that will soon be inflicted on them. I wish he had been with us when we visited the campus earlier in the day, to see the toughness beneath the surface of those young men and women of Baghdad University. Like most of the Iraqi we have met over the last few days, they are prepared for the worst, but they are determined not to make the worst ruin their daily lives.

Tomorrow afternoon, March 17, the date of the American ultimatum for Iraq to disarm or face war, we in the Asian Peace Mission will be travelling by land on two vans flying the Philippine flag to the order with Syria. Dita Sari, the labour leader from Indonesia, was offered a ride to the border this evening by the Indonesian ambassador, who was very concerned about her safety. She refused, saying she would leave only when the mission left. We are leaving late and cutting it close because all of us–Dita, Philippine legislators Etta Rosales and Husin Amin, Pakistani MP Zulfikar Gondal, Focus on the Global South associate Herbert Docena, our reporter and cameraman Jim Libiran and Ariel Fulgado, and myself–feel the same compulsion: we want to be with the Iraqi people as long as possible.

Mrs. Packletide's Tiger

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Loona Bimberton had recently been carried eleven miles in an aeroplane by an Algerian aviator, and talked of nothing else; only a personally procured tiger-skin and a heavy harvest of press photographs could successfully counter that sort of thing. Mrs. Packletide had offered a thousand rupees for the opportunity of shooting a tiger without over-much risk or exertion. However, when the opportunity came, she accidentally shot the goat, and the tiger died of fright, and she had to settle with Miss Mebin so that her version of the story would be the one to circulate.

?The release of the hostages by the military, had all the hallmarks of Mrs. Packletide?s tiger hunt,? said Ching Kiu Rewaja Chairman Rangamati Sthanio Shorkar Porishod, the local government head. Unlike the story by the Indian born writer Saki, there were no press photographs to show here, but radio and television and the carefully fed press releases had been prepared so that the story of the heroic release of the two Danish and one British engineer in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, would circulated unchallenged. There had been a few hiccups, and the two separate government press releases on the same day, explaining the circumstances of the kidnapping, had cast shadows on the otherwise well orchestrated adventure story.

Ching Kiu Rewaja sat in his big government office, surrounded by a large number of people vying for his attention. He gestured grandly for us to sit in a position of honour as tea and biscuits immediately appeared. He was busy signing things and would stop momentarily to look up and apologise to us for keeping us waiting. ?There is a subtle competition here, civil administration, police, and military all wanting credit. And they didn?t want to share the credit, hence this deceit.? However, while the chairman understood the underlying politics, despite his colourful analysis, he didn?t really know. No one besides the kidnappers and the military knew exactly what had happened on that night, or the subsequent morning. Post release, the Danish engineers in distant

Copenhagen, had reconstructed the hours preceding the kidnapping. ?After a seven hour walk through the jungle we were led to a bamboo cottage, during the night. Then the abductors went into the jungle, and after some hours they heard some shootings, and soldiers shouting, ?you have been released by the Bangladeshi Army?.?

The Brigadier General Rabbani, who headed the military in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, did speak to us, and was extremely cordial, but would not give an official answer. Neither his version, nor the extremely vague government press releases, explained how both the military and the abductors arrived at the same remote spot at the same time, particularly when it takes so many hours to get to. How the abductors escaped, when they had the place surrounded, is mysterious, and the fact that no one from either side was the slightest bit hurt in this confrontation is a bit surprising. Given the secrecy surrounding the issue, the rumours have been flying, but certain significant facts do emerge.

- The incident (which took place less than 500 metres of the military camp) was not an isolated one. People were advised to keep some money, in case they were stopped by hijackers. This was common knowledge.

- In internal discussions, (which the police and military deny), there had been talk of compensation, even for incidents of rape that had been reported.

- Though the government claims that they have advised all donors to take police escorts, there appears to be no document in support of this claim.

- The early mediators had been suspected of being on the ?take? themselves, and later people were shuffled.

- There is resentment in the Chittagong Hill Tracts for some of the ?developments? being planned, particularly the establishment of a 218,000 acre ?reserve forest? which will take over further land from hill people, and the proposed construction of two extra units of the Kaptai Dam.

- There is a certain degree of ?tolerance? for the criminal activities that go on in the military protected zones.

While in general people in the government and others who are seen to be recipients of foreign aid clearly want aid to continue, there are hill people who question this development process. ?Who is the development for? If there is no peace then what will it solve? Once development funds were given, crores of taka were given. Bungalows and roads were given, but what did it do for the average person? The roads made it easier for the military, and for bureaucrats to live in, but these did not affect the general people. It might appear that a road will lead to progress, but it has been seen that roads have been used for taking away the forest resources, the trees and the wood, it has made the forests barren, now we even have floods in the hill tracts which we have never had. This increased inflow of people have pushed the people further back. The local people do not get the benefits of this development,? says Prasit Bikash Khisha: Convenor UPDF, who?s party has been accused by some of having orchestrated the kidnapping. An association that UPDF vehemently denies.

Others like engineer Kjeld J Birch, Senior Advisor, CHT Water Supply and Sanitation disagrees with the withdrawal of Danish development aid. ?The hospitality here is very good and kind, so it is difficult to understand that things have to be closed down. I don?t feel unsafe. On a personal level I wouldn?t feel worried. We never used an escort, except when the ambassador was here. Never have I had any untoward experience. Neither my wife. The people we have been in touch with, have been very protective. I think there is an overreaction.? But Birch, who left an attractive job offer in Bhutan to come to one which offered him ?a challenge? and his wife who left a job to accompany him are now both unemployed, so they too have personal interests to protect.

It is therefore difficult to sift the ?truth? from this rubble. But certain changes will have to be in place before development in whoever?s definition can be in place. Information has to flow to the people. A misinformed public will construe the worst, and the rumours currently circulating within the Chittagong Hill Tracts certainly do not favour the government. There has to be a greater degree of transparency in the way things are conducted in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The military will have to be more accountable to the people in both Bangladesh at large and the hill people in particular. People not affiliated to the government, or not necessarily in full agreement with the peace accord, need to be involved in matters affecting the future of the hill people, and that the zone must no longer be treated as a military zone. Within Bangladesh and within The Chittagong Hill Tracts, a democratic system has to give weight to marginalized communities. If these issues get addressed, maybe the kidnapping will have done more for Bangladesh?s development than the players involved had originally envisaged.