25th March 1971. My eldest niece had just been born the day before. It was a premature birth. Amma had found a Mariam flower and the flower had bloomed, heralding the birth. She had stayed behind at the clinic. We had felt something was afoot, and Babu Bhai and I went out to try and get mother and child back from Dr. Firoza Begum’s clinic in Dhanmondi. Our home might not have been safer, but at least we’d be together. Friends were building roadblocks in the streets by then, and let us through reluctantly, warning us that we had little time.

We went along the narrow road by Ramna Police station to Wireless Mor, it being too dangerous to go along the main road. I climbed over the barbed wires on the boundary walls to get to my sister’s flat, but my brother in law felt it was too dangerous to go out, so I turned back. By then the tanks were on the streets.

I had fallen asleep, but woke up to the sound of gunfire. The wide red arcs of tracer bullets had lit up the sky. The only tall building nearby was the Hotel Intercontinental, where the meetings between Mujib and Bhutto had taken place, and where the foreign journalists were staying. The slum next to the Sakura Hotel and the nearby\ newspaper office were ablaze. We could hear the screams. Those who were able to escape the fire, ran into the machine gun fire waiting outside.

Abba (my father), Babu Bhai and I watched in silence. We had argued with Abba about Pakistan, but he had been victimised as a Muslim in pre-partition India, and would not support what he saw as the break up of the nation. That night he finally broke our silence by saying, “now there is no going back.”

We heard the gunshots all night, and there was a curfew the following day. Eventually when there was a small break in the curfew the day after, Abba went to get supplies, and Babu Bhai and I got my sister and her daughter to Nasheman, in Eskaton where we lived. We called her Mukti, meaning `freedom’. But relatives warned us that it was too dangerous to use that name, even if it was a nick name to be used only amongst ourselves. So Mukti became Mowli, and even after independence, the name stuck.

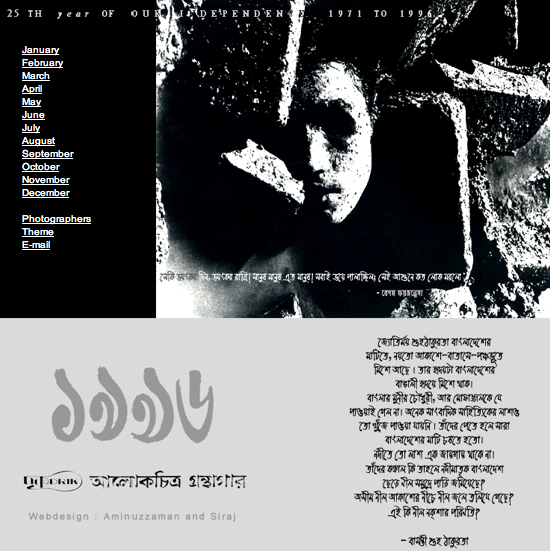

Twenty five years later in 1996, I tried to put together a collection of images of ’71 for our 1996 calendar. I am reminded of the introduction:

[Twenty five year ago, even longer perhaps, just a camera in hand, they had gone out to bring back a fragment of living history. Today, those photographs join them in protest. Peering through the crisp pages of the newly printed history books, they remind us, “No, that wasn’t the way it was. I know. I bear witness.”

The black and white 120 negatives, carefully wrapped in flimsy polythene, stashed away in a damp gamcha, have almost faded. The emulsion eaten away by fungus, scratched a hundred times in their tortuous journey, yellowed with age, bear little resemblance to the shiny negatives in the modern archives of big name agencies. They too are war weary, bloodied in battle.

So many have sweet talked these negatives away. The government, the intellectuals, the publishers, so many. Some never came back. No one offered a sheet of black and white paper in return. Few gave credits. The ones who risked their lives to preserve the memories of our language movement, have never been remembered in the awards given on the 21st February, language day.

25 years ago, they fought for freedom. They didn’t all carry guns, some made bread, some gave shelter, some took photographs. This is just to remind us, that this Bangladesh belongs to them all.]

Drik Calendar 1996

Today, embedded photojournalists with digital cameras, give us images of yet another aggression. This time, from the other side of the gun. The 50 clause contract that gives them access to imperial military units, like the unwritten rules that allow them access to presidential pools, ensure that `free’ media remains loyal to the warmongers. Will we ever get to see the images taken by the Iraqi photographers? Will their negatives die the same death? Will those images, like the bombed ruins of a magnificent city, be the only tattered remains of an aggression that the world allowed to happen? In ’71, the Seventh Fleet was stationed in the Bay of Bengal. The Mukti’s were not deterred by this show of power. They won us our independence. Today, after 43 more US military interventions across the globe, it is the Seventh Cavalry that bombs Iraq. And our own government, forgetting the lessons of history, forgetting that they tried to kill our unborn nation, turns against the will of its people. Our own police turn against us in our anti war rallies, to protect the biggest aggressor in history. These negatives may not survive, but the collective memory of the people of the world will, and our children will confront us in years to come.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

26th March 2003

* A flower from Arab deserts, used during labour to predict the time of childbirth.

** A working man’s cloth of coarse cotton, used as padding when carrying weight, to carry food, and to wipe away sweat.

Tag: Genocide

We Did Say No

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

My questions are many. Why is there no UN resolution against the United States, for blatantly initiating an unprovoked genocide? Whydoes not the UN Security Council, demand that the most habitual aggressor in recent history, disarm and destroy

its weapons of mass destruction? Why is it that despite our collective strength, the most we can muster is a passive condemnation of a mass murder? Whatever may happen after the bombs have dropped, we will not be able to hide our shame. It may not have been in our name, but we sat and watched. We allowed it to happen. It is a guilt that will haunt us. While I sit in anger, wondering how, despite all our rhetoric, we watched a nation being plundered, without raising a finger to stop it, this quiet reflection from Baghdad University campus brings homethe extent of our complicity. These are the people we allowed to be destroyed. Our lives will go on, and we will face another day. They will not. And we will be content because we had said no

Shahidul Alam

Mon Mar 17, 2003

===============================================================

At the College of English, it is most definitely springtime. Co-eds are chattering cheerily and they smile as we pass. "We are intent on finishing the syllabus, war or no war," says Professor Abdul Jaafar Awad. He tells us that during the Gulf War of 1991, he was discussing a doctoral dissertation with a student while American and British warplanes were bombing Baghdad. Jawad's determination to carry on despite the approach of war is shared by the students at his department.

Students at a class on Shakespeare are discussing Romeo and Juliet when we interrupt them. No, they say, they don't mind answering some questions from the Asian Peace Mission. They are carrying on with Shakespeare, but their answers show that morally they are on war footing. What do they think of George Bush? "He is like Tybalt, clumsy and ill-intentioned," says a young woman in near perfect English. What do they think about Bush's promise to liberate them? Another co-ed answers, "We've been invaded by many armies for thousands of years, and those who wanted to conquer us always said they wanted to liberate us." What if war comes, how would they feel? Another says, "We may not be physically strong, but we have faith, and that is what will beat the Americans." A young professor tells me, "I love teaching, but I will fight if the Americans come." These are not a programmed people. Saddam Hussein's portrait may be everywhere, but there are not programmed answers. In fact, we have hardly encountered any programmed responses from anybody here in the last few days. Youth and spring are a heady brew on this campus, and it is sadness that we all feel as we speed away, for some of those lives will be lost in the coming war. As one passes over one of the bridges spanning the Tigris River, one remembers the question posed by Dr. Jawad: "Why would today's most powerful industrial country wish to destroy a land that gave birth to the world's most ancient civilization?" It is a question that no one in our delegation can really answer. Control of the world's second biggest oil reserves is a convenient answer, but it is incomplete. Strategic reasons are important but also incomplete. A fundamentalism that grips the Bush clique is operative, too, but there is something more, and that is power that is in love with itself and seeking to express that deadly self-love.

An American journalist I meet at the press centre says the people are carrying on as usual because they are in deep denial of the power that will soon be inflicted on them. I wish he had been with us when we visited the campus earlier in the day, to see the toughness beneath the surface of those young men and women of Baghdad University. Like most of the Iraqi we have met over the last few days, they are prepared for the worst, but they are determined not to make the worst ruin their daily lives.

Tomorrow afternoon, March 17, the date of the American ultimatum for Iraq to disarm or face war, we in the Asian Peace Mission will be travelling by land on two vans flying the Philippine flag to the order with Syria. Dita Sari, the labour leader from Indonesia, was offered a ride to the border this evening by the Indonesian ambassador, who was very concerned about her safety. She refused, saying she would leave only when the mission left. We are leaving late and cutting it close because all of us–Dita, Philippine legislators Etta Rosales and Husin Amin, Pakistani MP Zulfikar Gondal, Focus on the Global South associate Herbert Docena, our reporter and cameraman Jim Libiran and Ariel Fulgado, and myself–feel the same compulsion: we want to be with the Iraqi people as long as possible.

The War We Forgot

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Iqbal had asked me when we first met. “Bhaiya, where are Barkat and Salaam’s graves?” I didn’t know. He was 10, I was 39. As a 15 year old in 1971, I had felt the warm flush of victory as I held a Pakistani Light Machine Gun in my hand. I hadn’t really won it in battle, but only recovered it from a burning military truck. But the joy was just as much. That was the time when a rickshaw wallah had refused to take my fare, because he had heard me greet a friend with ‘Joy Bangla’ (freedom for Bengal, the 1971 slogan symbolizing freedom from Pakistani rule). Things had changed, and the promise of our own land had slowly been eroded by politicians and military rulers who had lived off our dreams. Each time we became skeptical, each time we sniffed that something other than ‘Shonar Bangla (Golden Bengal)’ was in their minds, they led us on with vitriolic rhetoric. Eventually, as on that day in 1994, I too had forgotten. I didn’t know where Salaam and Barkat’s graves were. I had never heard of Dhirendranath Datta. More importantly, I didn’t care. But Iqbal did. Born long after Salaam and Barkat’s bodies had merged with the soil, Iqbal only knew of this great battle that we had fought. Though the heroes had changed depending upon who ruled the country at any particular time. Salaam and Barkat were beyond dispute. They were not a threat to anyone. They didn’t apply for a trade license, or bid for a government tender. It was safe for the history books to remember them. Remembering Hindus or women was a bit more problematic.

My search for these other heroes, the ones with cameras, began in 1994. After Iqbal reminded me that I had forgotten. It was in the Paris office of Sipa that Goksin Sipahioglou, excited at my presence ran down the stairs and brought back with him an armload of slide folders. It took a while for it to sink in. These were the first colour photographs of the Muktijudhdho that I had ever seen. We had heard that some of these photographs had been published. But our only source of news at that time was Shadhin Bangla Radio. It talked of the glory of our freedom fighters, of how they were fearless against enormous odds. Of their glory in battle. M R Akhtar Mukul in ‘Chorompotro’ was the one voice we longed for. We chuckled as he talked of the plight of the Pakistanis. His wry but animated voice, muffled by the blanket we hid under, and barely audible in the turned down volume of the transistor radio, gave us hope, and kept us going through the dark nine months.

It was Abbas’ photographs that Goksin had brought for me. Later that month, in the back garden of a house in Arle, I met Don McCullin. Don was excited about the show I wanted to do, and unhesitatingly agreed to give us pictures. I found Abbas, at a beach near Manila, quite by accident. Both of us had been following the golden late afternoon light in a summer evening in Manila beach. Abbas too was excited. He wanted to be part of the show. Michele Stephenson and I had been in the same jury of World Press Photo on two occasions, and I had plenty of time to tell her about my plans. She invited me to New York and arranged for me to go through the archives of her magazine, Time. It was in the basement of the Time Life Building in the Avenue of the Americas, that I came across the daily bulletins that the reporters had sent in.

Memories flooded through my mind as I remembered those harrowing days and nights. I remembered the screams of people being burned alive as the flame throwers belched fire at the Holiday office near the Hotel Intercontinental.

Most of the people who died were the people who slept in the streets and the slum dwellers around the newspaper office. Those who chose to escape the fire ran into a hail of machinegun bullets. My father, mother, Babu bhai and I, watched quietly from our verandah in Nasheman on New Elephant Road. My dad had suffered from Hindu bhodrolok prejudice in the pre-partition days, and had never supported the break-up of Pakistan. And we would have great fights in the home, the younger ones wanting independence, Dad’s generation feeling things could be patched up. That was the night Dad said it was over. No longer could we ever be one Pakistan.

I excitedly went through the reams of paper. Each scrap of news had a meaning for me. I could relate to these news bulletins. I remembered the horror of those nights. As I thumbed through a tattered red diary, I noticed the skimpy notes of a photojournalist as he traveled through Jessore. I remembered Alan Ginsberg’s poem. It was David Burnett’s diary. Several years later as David and I met in Amsterdam in yet another World Press Jury, I told him where his diary was. In Kuala Lumpur, Dubai, Delhi, and so many other cities have I picked up the scraps of evidence that would help me piece this jigsaw together.

It was in Paris that I spoke excitedly of my plans to Robert Pledge, the president of Contact Press Images. Robert shared my enthusiasm for the project, but I harried him with my feverish frenzy. We couldn’t wait, we had to do it now. That now has taken over six years. But in these years we have made the most amazing discoveries. The stories, the images, the people we have come across, make up the life of this exhibition. It is the war veterans, the men and the women in the villages of Bangladesh, who fought the war, the forgotten heroes with their untold stories, the men and women who were killed and maimed, the women who were raped that this show is dedicated to. It is not a nostalgic trip for us to romanticize upon. It is for Iqbal and his friends to know that Barkat and Salaam, were more than simply names in history books.

Shahidul Alam

November 2000. Dhaka