Practical session under a banyan tree on the banks of the river Mahananda, Chapainawabgonj. ? Reza/Drik

Practical session under a banyan tree on the banks of the river Mahananda, Chapainawabgonj. ? Reza/Drik

?Kamera tulen?. Elsewhere, one would think a hundred times before pointing a camera. Permission, legality, issues of representation, all came into play. In any Bangladeshi village, getting people out of your lens is the problem. A cluster of heads surround the LCD. Peals of laughter. Old toothless smiles, a little baby held up so she can see. The disappointment of being left out. There might be serious issues to be dealt with, but right now being photographed was all that mattered.

Fourteen-year-old Rabeya, a member of our adolescent group, was taking photos in this beautiful location. I want everyone to live in such a beautiful environment. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Fatema Akter Hasi; 14

Fourteen-year-old Rabeya, a member of our adolescent group, was taking photos in this beautiful location. I want everyone to live in such a beautiful environment. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Fatema Akter Hasi; 14

Trainees from?Barguna. ? Jeevani Fernando

Trainees from?Barguna. ? Jeevani Fernando

With every intervention, one has concerns. Entering people?s lives, creating expectations, making friends, all have to deal with the disengagement that follows. It was people you were dealing with. How do you walk out of a life you have changed, perhaps forever? What do you leave behind, how much do you take away? These were difficult questions and we didn?t really have answers. But we?d tried it before, in cities and in villages. The remarkable transformations it had made to some children?s lives made the risk worth taking.

This is Shorifa Begum on her wedding day in Taherpur. She is a bride at eighteen years old. Shorifa did not want to get married. She stopped her education because she could not afford to continue it. Then her mother forced her to get married to a man who agreed to have a cheap wedding ceremony. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ??Morium Khatun; 16

This is Shorifa Begum on her wedding day in Taherpur. She is a bride at eighteen years old. Shorifa did not want to get married. She stopped her education because she could not afford to continue it. Then her mother forced her to get married to a man who agreed to have a cheap wedding ceremony. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ??Morium Khatun; 16

Md. Moinuddin training in Jamalpur. ? Aminuzzaman/Drik

Md. Moinuddin training in Jamalpur. ? Aminuzzaman/Drik

There were aesthetic concerns too. In talking of composition, rules of thirds, moments, balance, were we suppressing their spontaneity? Did we impinge upon their way of seeing? Were we erasing their natural ability to tell stories? We needn?t have worried. Sure, they tried things out. Pictures were created with remarkable composition. Balanced frames with well-placed elements formed stylised images that a trained photographer would have been proud of, but we had underestimated their instincts. Our fears of over intrusion were unfounded. The most striking images resulted not from our training, but because they had a voice. They could now tell their own stories and no one was going to get in their way, not even their teachers. The proud, chest-out, stiff at attention pose, that thwarted every photographer looking for something ?natural? was very much part of that expression. The loud coloured d?cor that would embarrass the urban genteel, was shown off with panache. Quirky images of everyday scenes, seen the way only children see, were the nuggets that glittered through our light box.

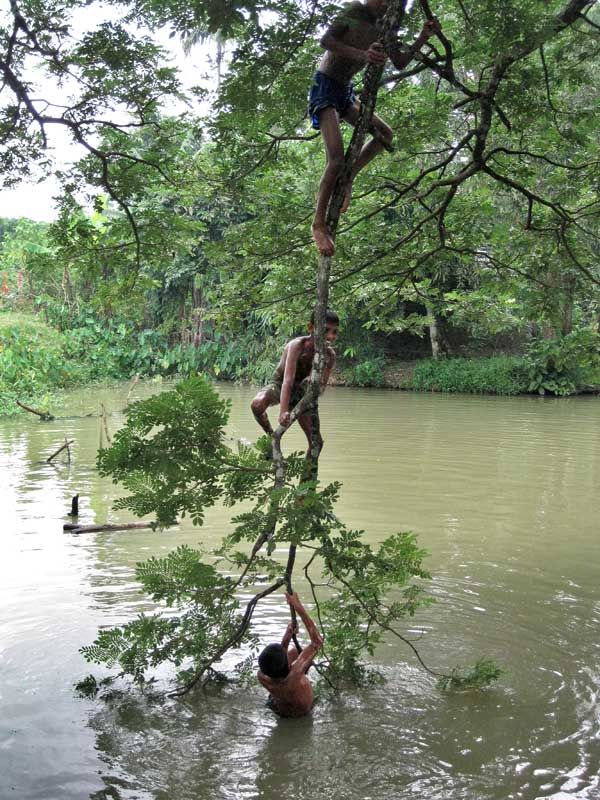

A group of children play in a local pond by climbing onto the tree and jumping into the water. They don’t go to school as their fathers are rickshaw pullers and do not earn enough to educate them. The parents are also not fully aware of the value of education. Barguna, 2009. ??Mohammad Jashim Uddin; 18

A group of children play in a local pond by climbing onto the tree and jumping into the water. They don’t go to school as their fathers are rickshaw pullers and do not earn enough to educate them. The parents are also not fully aware of the value of education. Barguna, 2009. ??Mohammad Jashim Uddin; 18

This is my uncle Shahidul’s goat. Every evening my uncle plays with the goat by holding up a leafy branch for him to jump up and eat. I watched this and took a photo. I also think that if the goat could become a human, then it might not need to jump like this. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ? Md. Sala-uddin Ahmed; 16

This is my uncle Shahidul’s goat. Every evening my uncle plays with the goat by holding up a leafy branch for him to jump up and eat. I watched this and took a photo. I also think that if the goat could become a human, then it might not need to jump like this. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ? Md. Sala-uddin Ahmed; 16

There were quiet reflective moments too. Their realities, the every day challenges, the matter of factness with which they dealt with hurdles, had an immediacy that would humble a trained professional. Layered between romantic images in fields of Kash, looming clouds over flowing rivers, coiled branches silhouetted against stormy skies, were photographs that talked of strife. People less able who insisted on being able. Children longing to be children. A much too young bride. Another young mother to be, gingerly treading through a treacherous path. Absent are the images they were not allowed to show. That threatened a patriarchal society?s image. Pictures they had been forced to delete. Pictures they had staged, as their reality was being suppressed. To delete, to stage, to deal with censorship. These are things they hadn?t been taught. They were learning on the fly. Dealing with situations as best as they could. They were coping with life. Perhaps the ultimate lesson.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

This woman is removing paddy from the basket after it is boiled. She keeps her feet on a jute bag so that they don’t get burnt. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

This woman is removing paddy from the basket after it is boiled. She keeps her feet on a jute bag so that they don’t get burnt. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

Nature photographer. ? Reza/Drik

Nature photographer. ? Reza/Drik

Sohel, 12, lives in Nandina and works in Mostafa Bakery making biscuits and other snacks. He helps his family with his daily wages. It amazes me that a young boy like Sohel has to work for a living instead of going to school. I do not want any child to work for a living. We have to create awareness among people about child labour. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Md. Amir Hossain Apon; 14

Sohel, 12, lives in Nandina and works in Mostafa Bakery making biscuits and other snacks. He helps his family with his daily wages. It amazes me that a young boy like Sohel has to work for a living instead of going to school. I do not want any child to work for a living. We have to create awareness among people about child labour. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Md. Amir Hossain Apon; 14

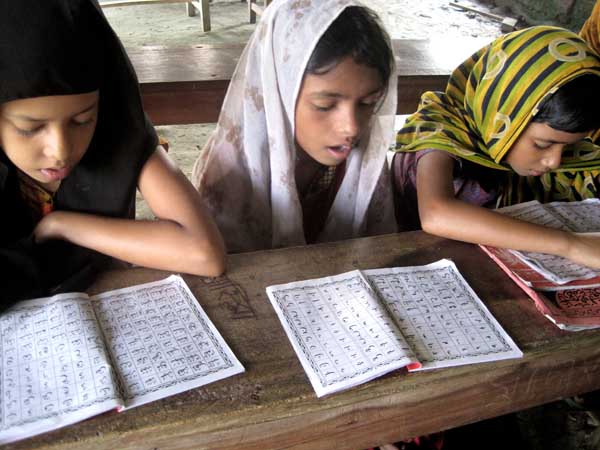

Amy and Rumi are 11 and 12 years old. They go to the madrasa to learn Arabic every morning. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

Amy and Rumi are 11 and 12 years old. They go to the madrasa to learn Arabic every morning. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them.

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them. When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’

When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’