http://www.newint.org/issue377/exposure.htmI took this photo on World Women's Day, 8 March 2004. It shows survivors of acid attacks. Such attacks are still made against women who are accused of violating social codes. Here they are staging an 'awareness drama'. Amra aar eka noi ('We Are Not Alone') was written and performed by survivors. Their dreams have been shattered, their faces and bodies charred by a liquid fire - acid. But their indomitable courage and will-power to rebuild their lives and move forward is strengthened by everyone telling them they are not alone. All the performers use masks, but at the end of the drama they take the masks from their faces and introduce themselves to the audience. They are so emotional. I took the photo to show this emotion, which I think is very difficult to describe unless you have felt it yourself. Abir Abdullah Bangladesh

Category: Southern Exposure

Like Every Day

As the exhibition by women photographers celebrating International

Women’s Day, ends at the Drik Gallery, an Iranian woman explores the

everyday lives of women. Shadi Ghadirian was one of the photographers

featured in the recent Chobi Mela III.

http://www.newint.org/issue374/exposure.htm

I am a woman and I live in Iran. I am a photographer and this is the

only thing I know how to do. I began work after completing my studies.

Quite by accident, the subjects of my first two series were ‘women’.

However, every time I think about a new series, in a way it still

relates to women.

Perhaps the only idea outsiders have of Iranian women is a black chador.

I try to portray all our aspects. And this completely depends on my own

situation. When I did this series of photographs, I had just graduated.

The duality of life at that time provided the motive: one cannot say to

what time the woman belongs; a photograph from two eras; a woman who is

dazed; a woman who is not connected to the objects in her possession.

After marriage it was natural that vacuum cleaners and pots and pans

found their way into my photographs; a woman with a different look; a

woman who, no matter in what part of the world she is living, still has

these kinds of apprehensions. At this moment a woman is consigned to a

daily repetitive routine. For this reason I named the series Like Every

Day.

Now I know what I wish to say with my photographs. Many of them have

shown women as second-class citizens or the censorship of women. I wish

to continue speaking about women because I still have a lot to say.

These are my words as a woman and the words of all the other women who

live in Iran, where being a woman imposes its own unique system. The

photographs are not authentic documentation. I take them in my studio,

but they deal with current social issues all the same.

Shadi Ghadirian, Iran

The Price for "Progress"

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

http://www.newint.org/issue372/exposure.htm

Shinzo Hanabusa is yet another artist to be featured in the upcoming festival of photography, Chobi Mela III. Hanabusa’s work on Japanese farmers provides a fascinating insight into the cost of ‘progress’, in a nation like Japan.

The Second World War had adversely affected farming in Japan. I began producing a documentary on farming in 1962. The farmers were not getting a fair price for their milk. Then Japan started importing powder milk and things got really bad. In 1966 I heard rumours that the farmers in Akita were setting up a resistance movement. Following newspaper leads I went over to the locality. I was very upset, when I saw them throw the milk from the bridge as a sign of protest, at the fact that they had been reduced to this. But a big publication, Ewanami Shoten, printed the photograph and it helped turn things around a bit, so I felt good afterwards. I have since become known as ‘The Milk Photographer’. I hope the publication of this photograph in Southern Exposure helps farmers around the world get a fair price for their produce.

Shinzo Hanabusa, Japan

Kwaito Culture

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

Neo’s work is one of the 40 exhibitions to be seen at the coming festival of photography Chobi Mela III. The festival opens on the 6th

December 2004 in Dhaka.

http://www.newint.org/issue371/exposure.htm

This picture is part of my self-initiated project SA Youth ID – Kwaito Culture, a personal and reflective body of work about the changes in the lives of South Africans in the new democratic country. The word Kwaito is derived from the Afrikaans kwaai – ‘angry’. In colloquial slang, negative words or phrases often acquire a positive connotation or ‘cool’ status. The language of Kwaito is Isicamtho, South African township slang.

While working on the project it became clear to me that the youth of South Africa refuse to be condemned by the politics of the past (apartheid) but choose to find their own identity. They have been developing one which is truly and proudly South African – Kwaito culture. It’s about peace, love and unity; about being yourself and loving yourself enough to be YOU.

I am a 31-year-old female photographer. I did my photography studies in Cape Town and Pretoria. I then freelanced in Mmabatho, my hometown, before moving to Johannesburg. My original interest was in film and television. But I could not pursue my dream because of the political situation in South Africa at the time. In 2000 I joined The Star newspaper. I later spent a year teaching at Pathshala South Institute of Photography in Bangladesh.

I have always been inspired to change the gender imbalance in photography. My recent achievement – the first woman CNN Africa Photographer of the Year – has motivated me to devote my time to this even more, popularizing the profession among other wome and ploughing back the knowledge I have gained by making a difference in the lives of others. I continue to work at The Star, specializing in news, fashion and theatre photography.

Neo Ntsoma

South Africa

A Different World

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

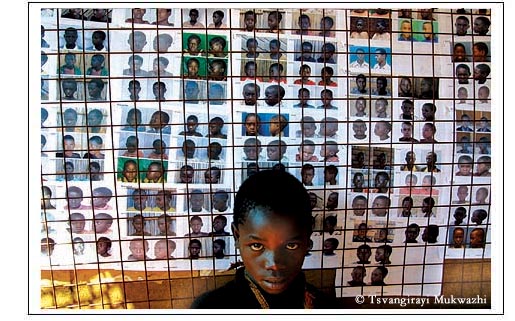

I took the picture at one of the refugee camps in Tanzania set up by the government. I was trying to show the plight of the children who were lost and never reunited with their families. It was a hot and sunny day and I was a bit tired, having visited several camps in that area. 8 year old Kindaya Chikelema from Burundi stood in front of a notice board. More than 4000 children were lost while fleeing the war in Brurundi and Rwanda. Kindaya was one of the lucky children to be found by his parents after they saw his picture on the notice board at one of the camps.

Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi

…

A Different World

…

The many letters mailed all over the world had produced few results and it was ‘door to door’ time. I had placed the loose collection of prints on Dexter Tiranti’s table at the New Internationalist Magazine in Oxford. I remember Dexter’s letter the following year, regretting that he could only use six images from our agency, as the selection already had too much from Bangladesh. That started a long relationship between our organizations and led to my involvement in Southern Exposure, a platform, like Drik, for promoting photographers from the majority world. The Net has helped, but most of our contacts have come from information gleaned on motorbike rides down the back streets of Hanoi, or a meeting in a paddy field outside Beijing, or a visit to a museum in Tehran or similar opportunities for meeting photographers, whom I would not have come across in the mainstream directories. I remember excitedly going through boxes of prints that only fellow photographers or close friends had seen. Of newly found friends telling me of people I must meet. Friends from the Drikpartnership, students, colleagues at other agencies and at World Press Photo. Friends, who like us, have believed in the plurality of image sources and have been active in trying to bring about a change.

The images too have been different. These are not the ‘developmental images’ extolling the virtue of the latest World Bank fix, or the ‘news’ images that choose not to see beyond editorial briefs. The abandon of the flutist in Bangladesh or a ‘sweet fifteen’ dance in Peru, or the careless joy of the children on the branch of a tree in South Africa represent a personal involvement of the photographer, and a relationship with the photographed, often missing in the ‘big stories’ that the major agencies send their photographers to ‘capture’. Little of what you will see here is newsworthy to mainstream media. No hype reaffirms the success of a particular development plan. It is revealing that these majority world photographers have an insight and a sensibility that is strikingly different from that of their big name visitors. It is telling that an altogether different story emerges when a different pair of eyes is behind the lens. In their own back yard, they see a different world.

..

Shahidul Alam

See Full Calendar