![]()

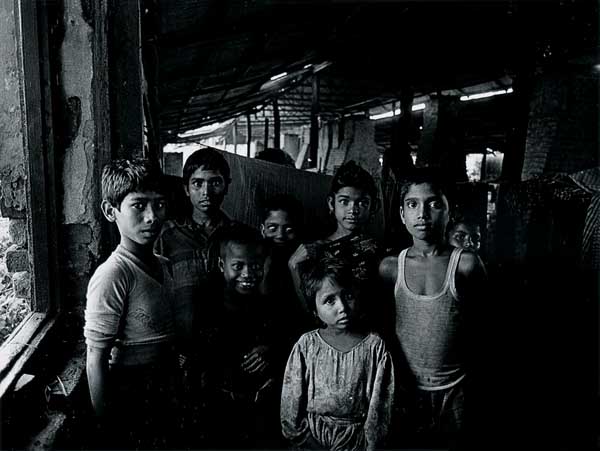

Even after years of playing Pied Piper with a camera, I am still taken aback by children insisting on being photographed. It was September 1988, and we had had the worst floods in a century. These people at Gaforgaon hadn’t eaten for three days. A torn saree strung across the beams of an abandoned warehouse created the only semblance of a shelter. Their homes had been washed away. Family members had died. Yet the children had surrounded me. They wanted a picture.

It was dark in that damp deserted warehouse, but the broken walls let in wonderful monsoon light, and they jostled for position near the opening. It was as I was pressing the shutter that I realised that the boy in the middle was blind. He had pushed himself into the centre, and though he wasn’t tall he stood straight with a beaming smile.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CARE

Clip on story of the blind child, from keynote presentation on citizen journalism at 50th Anniversary of World Press Photo in Amsterdam.

I’ve never seen the boy again, and today I question the fact that I do not know his name. But he has never left my thoughts and often I have wondered why it was so important for that blind boy to be photographed.

It’s happened elsewhere, in boat crossings at the river bank. In paddy fields heavy with grain, in busy market places. A shangbadik (literally a journalist, but in practice any person with a half decent camera) was hugely in demand. They refused to take the fare from me at the ferry ghat. Opened up their hearts and told me their most personal stories. Confided their secrets, shared their hopes. Never having deserved such treatment it has taken a while for me the photographer, to work out why being photographed meant so much to that blind child.

The stakeholders of Bangladeshi newspapers are the urban elite. Consequently stories from the village are about the exotic and the grotesque. Village people exist only as numbers, generally when plagued by some disaster and only when figures are substantial. A photograph in a newspaper, regardless of how token the gesture, is the only time a villager exists as a person. A picture on a printed page would have lifted that blind boy from his anonymity. That humbling thought stays with me whenever I am feted as a shangbadik in some small village. I receive their gift of trust gently, careful not to break the delicate contents.

It was as a photographer of children that I had begun my career. It was way before 9/11 and one could make appointments with strangers and go to their homes. I took happy pictures of kids, and parents loved them. It was easy money, except when I would photograph the children of poor parents. They loved the pictures but couldn’t afford to pay, so I would quietly leave the pictures behind and pay the studio out of my pocket. Back in Bangladesh, the only way I could make money was as a corporate photographer, but something else was happening. We were in the streets, trying to bring down a general who had usurped power. I didn’t know it then, but I was becoming a documentary photographer. Suddenly taking pictures of children meant more than smiling kids on sheepskin rugs.

As the pressure against the general mounted, I photographed children who joined the processions. The night he stepped down, I photographed a little girl with a bouquet of flowers. She was out with her dad in the middle of the night, celebrating the advent of democracy.

I am back in Kashmir eight months after I had been here photographing the advent of winter. The valleys of this fertile land are green with new crops,

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

but many of the homes are still to be rebuilt. As I walked through the rubble, the kids again wanted to be photographed.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Najma came running, her bright red dress popping out of the green maize fields.Unsure at first, she smiled when I told her she had the same name as my sister.

Shahidul Alam/Drik/CONCERN

Zaheera, a cute girl with freckles, gathered her friends and sang me nursery songs. But my thoughts are far away. Despite the laughter and the nursery songs very different sounds enter my consciousness. I remember the children screaming on the night of the 25th March 1971, when I watched in helpless anger as the Pakistani soldiers shot the children trying to escape their flame throwers. The US had sent their seventh fleet to the Bay of Bengal, in support of the genocide. Today, as I remember the Palestinians and the Lebanese that the world is knowingly ignoring, I can hear the bombs raining down on Halba, El Hermel, Tripoli, Baalbeck, Batroun, Jbeil, Jounieh, Zahelh, Beirut, Rachaiya, Saida, Hasbaiya, Nabatiyeh, Marjaayoun,Tyr, Jbeil, Bint Chiyah, Ghaziyeh and Ansar and I hear the screams of the children. Piercing, wailing, angry, helpless, frightened screams.

News filters through of the children killed in the latest bombing. The photographs have kept coming in, horrific, sad, and disturbing. Mutilated bodies, dismembered children, people charred to ashes. But none as vulgar as those of Israeli children signing the rockets. Death warrants for children they’ve never known.

I remember my blind boy in Gaforgaon. The Lebanese and the Palestenians are also people without names. Their pain does not count. Their misery irrelevant, their anger ignored. Sitting in far away lands, immersed in rhetoric of their choosing, conjuring phantom fears necessary to keep them in power, hypocritical superpowers fail to acknowledge the evil of occupation. The ‘measured response’ to a people’s struggle for freedom will never in their reckoning allow a Lebanese or a Palestinian to be a person.

When greed becomes the only determining factor in world politics. When the demand for power, and oil and land overshadows the need for other people’s survival, I wonder if those screams can be heard. I wonder if those Israeli children will grow up remembering their siblings they condemned. I wonder if through all those screams the war mongers will still be asking “why do they hate us”?

11th August

Siran Valley, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan