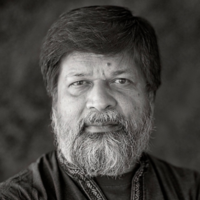

Interview with Shahidul Alam by Daniel Boetker-Smith

In one of his first major interviews since the events of late last year, Alam talks to Daniel Boetker-Smith about the upcoming festival, the political power of photography, and the state of the medium in Bangladesh, South Asia and beyond.

DBS: Given recent events that we have all followed closely, how has planning for this Festival been different to previous years?

SA: The last few months have meant that this year’s festival is coming back to its roots. Chobi Mela began as a very small event, and over the past 20 years it grew significantly in stature. But this year, we are activating a diverse range of less formal exhibition venues around Dhaka. This shift is one of necessity, because Chobi Mela is not an organization that everyone in Bangladesh wants to work with at the moment—we are seen as dangerous. A lot of previous supporters and sponsors of the festival are businesses in Dhaka, and right now they are being tested. They know that their decisions are being monitored and that there is high level of government surveillance surrounding the event. Because of this, we have had to be more inventive, finding new ways to show work, utilizing different types of exhibition and event spaces for photographers and audiences. Some public venues and government-owned buildings are no longer available to us, and we are choosing to see this as an opportunity to move away from the traditional ‘white cube’ mode of presentation, to a much more raw and community-oriented festival.

For this year’s festival, we are also putting a lot of emphasis on education. From past experience, we know that a lot of the visitors are educators, and we are taking the opportunity to rethink and revisit photographic education internationally, as well as in this region. So, at this year’s event, there’s a big emphasis on archives—we have brought together a series of different projects that look at the politics of the archive, funding, collective memory, and the physicality of archives. We are presenting the Kashmir Photo Collective, the Rohingya Archive, the Burj al-Shamali collection, and the Bangladesh Garment Sramik Sanghati, all of which provide insights into the social responsibility of archives. We have also been doing some research into vernacular photography and local photographic studios operating in small towns in Bangladesh, which has turned into a sociological project as much as an image-based one.

One of the key exhibitions at the Festival contains the work of the late Rashid Talukder, one of the great photojournalists of Bangladesh. Before he passed away in 2011, he handed over his entire back-catalogue of images to us. He is most famous for photographing in the killing fields of Rayerbazar in December 1971, during the last days of the Bangladesh war for independence. During this period, hundreds of Bengali journalists, teachers, intellectuals and artists were murdered by the Pakistani Army. In fact, December 14th is still observed in Bangladesh as the “Day of the Martyred Intellectuals.” With access to Talukder’s image archive, we were able go through and explore the huge amount of wonderful work he made before and after the war, including images of ordinary people and everyday events from all over Bangladesh. This part of his archive is wonderfully extensive and has never been seen by the public before.

DBS: On top of all this, you’re presenting some international figures of importance as well. Given recent events, have you had any issues with travel plans or visa applications?

DBS: Tell me more about your advisory panel. It seems to be a new step for Chobi Mela.

SA: Yes, this is a new direction. We have set up a panel of advisors—a list of respected people from a diverse set of disciplines. This stems from our belief that photography should not be restricted, and should always be contextualized with a much wider lens in terms of how it fits into the local social fabric. We identified people who have played an important role as citizens in Bangladesh and beyond—they are scholars, artists, lawyers, human rights activists, and finance people who are prominent in my country and region, and who have spoken out in the past. These voices are giving us a new perspective and fresh guidance in these challenging times.

DBS: What do you think the future holds for the Festival?

SA: At the moment, we are currently constructing a new 10-storey building to house Drik Picture Library and Pathshala South Asian Media Institute. Drik gave rise to Pathshala twenty years ago, and the new building that will house them both will facilitate a new synergy between the two organizations. This will have a positive impact on Chobi Mela, too.

In the past, we have supported and nurtured other festivals and initiatives in the region. Currently, there are over 19 photography festivals in India, and events such as Photo Kathmandu and Delhi Photo Festival have been hugely successful! China also has a huge number of festivals. We hope to continue to collaborate with passionate and engaged people in the region—not just in Bangladesh—and try to include them within the Chobi Mela team, enabling us to grow and move forward. We have started partnering with organizations to share the exhibitions from Chobi Mela internationally, and we are looking at how we can transport what we do here to a much wider audience.

DBS: What do you hope people in Bangladesh, as well as around the entire world, learn from your tireless efforts to continue with Chobi Mela?

SA: Chobi Mela has and will continue to be about bringing people together and, more importantly, bringing them to Bangladesh. The nation does take pride in this festival—it’s a flagship event in Dhaka—but it has also become a pilgrimage for photographers internationally. Chobi Mela has become an entrance for foreign visitors into the culture of Bangladesh, and I find it wonderful that people come back again and again, and in turn have become part of the extended Chobi Mela family. Through this year’s event, we hope to make a statement that we can’t be ignored or discarded, and that we are ready and willing to fight. And finally, we want the world to know that Chobi Mela is still here, and will be for a long time.

Editor’s Note: Chobi Mela was founded in 2000, and is organised by Drik Picture Library Ltd. and Pathshala South Asian Media Institute. The tenth edition of Chobi Mela will be held on February 28 till March 9, 2019. For more information on tickets and events, check out their website.