Tag: Pathshala

Countdown to Chobi Mela VI

Are you dreaming of coming to Chobi Mela VI or wishing you were coming?. A wish is voluntary and you make it consciously and have some power over making it come true.? Dreams on the other hand by definition, involve our unconscious mind. Do we have power over our dreams? Or do they have power over us? Can we make a wish come true ? 10 days to go to find out.

Yes, the countdown has started and taking a closer look at behind the scenes?of the festival?was Channel I, one of the partners of the Chobi Mela festival.

M. Mahbubur Rahman meticulously checks colours of prints. Photograph Habibul Haque

Shahidul Alam, Festival Director on Chobi Mela VI: Our right to dream on for a better majority world. Photograph Mahbub Alam Khan

Chobi Mela VI Press Conference

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

PRESS RELEASE

Chobi Mela VI to Open a Portal to a Restive World of Dreams

?All that we value, that we strive to uphold, all that gives us strength, has been made of dreams?

Dhaka, Bangladesh. 28 December, 2010😕 The Chobi Mela VI – International Festival of Photography will be held from 21 January to 3 February, 2011 in Dhaka Bangladesh and will present the work of creative artists participating from 30 countries. The festival with its theme ?Dreams? is designed to be a birthplace of ideas, and a crossover meeting point for many artists. It will open a portal to a mystical world of images showcasing new trends in photography and bringing to the fore issues of our troubled world.

The unique festival will be launched on the 21 January, 2011 at the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. Parallel exhibitions will be held at Alliance Francaise, The Asiatic Gallery of Fine Arts, The British Council, Drik Gallery, The Goethe-Institut and the Lichutala at Faculty of Fine Arts, Dhaka University. In congruence with the exhibitions there will be 8 workshops, 2 portfolio reviews and a week-long discussions, seminars and lectures at Goethe-Institut Auditorium that will initiate debates and discussions on issues central to contemporary photographic practice.

The main attraction on the 22 January at Goethe-Institut will be a video conference with Dr. Luis Moreno-Ocampo, Prosecutor, International Criminal Court.? In this position, his mandate is to select and trigger investigations and prosecutions of the most serious crimes of concern to the international community, namely genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. The Inaugural ceremony and the evening presentations will also be broadcast ?Live through Internet? at: www.drik.tv.

The first Chobi Mela festival (Dec.1999-January 2000) was launched by Drik and Pathshala South Asian Media Academy to fill the need for a forum for sharing work and ideas, a platform for debate that was missing on this side of the globe. This inaugural festival focused on ?Differences? in the world we live in and in a sense was prophetic. The twin towers disaster followed and buried beneath the rubble the freedoms that the world has since lost. ?In a world ravaged by war, to turn to ?Dreams? after ?Differences?, ?Exclusion?, ?Resistance?, ?Boundaries? and ?Freedom? is to return to what holds us together in the face of all our obstacles, the focus of all our longings. In a vastly unequal world, it is our insistence on justice and our ability to ride the waves, which still keeps us dreaming,? says Shahidul Alam, Festival Director and Managing Director of Drik. ?I dream that Chobi Mela will play a role in re-writing the history of photography, and correcting the extremely Eurocentric version of history that is currently propagated.?

Many bodies of work that went on to become well known were first shown in Chobi Mela. Considered to be the most demographically inclusive photo festival and the resulting pollination has led to many exciting exchanges, and given rise to several new festivals in the region for which Chobi Mela has been the catalyst.

Ensuring the general public?s access is an important part of the festival and admission for the festival is free. Mobile exhibitions on rickshaw vans are now a trademark of the Chobi Mela festivals. The festival provides an opportunity not only to enjoy the outstanding work of national and international photographers but also raises important social issues critical to our existence.

###

Chobi Mela Site

Chobi Mela Blog

For more information please contact Chobi Mela Secretariat

House 58, Road 15A (New),?Dhanmondi, Dhaka 1209

Tel +8802 8112954, 9120125, 8123412

Media Manager:

Qamruzzaman:

Tel: +8801911224884

Liason and Communication:

Chulie de Silva:

Tel: +8801927122141

WikiLeaks cables: Bangladeshi 'death squad' trained by UK government

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Rapid Action Battalion, accused of hundreds of extra-judicial killings, received training from UK officers, cables reveal

By Fariha Karim and Ian Cobain

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 21 December 2010 21.30 GMT

The British government has been training a Bangladeshi paramilitary force condemned by human rights organisations as a “government death squad”, leaked US embassy cables have revealed.

Members of the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), which has been held responsible for hundreds of extra-judicial killings in recent years and is said to routinely use torture, have received British training in “investigative interviewing techniques” and “rules of engagement”.

Details of the training were revealed in a number of cables, released by WikiLeaks, which address the counter-terrorism objectives of the US and UK governments in Bangladesh. One cable makes clear that the US would not offer any assistance other than human rights training to the RAB ? and that it would be illegal under US law to do so ? because its members commit gross human rights violations with impunity.

Since the RAB was established six years ago, it is estimated by some human rights activists to have been responsible for more than 1,000 extra-judicial killings, described euphemistically as “crossfire” deaths. In September last year the director general of the RAB said his men had killed 577 people in “crossfire”. In March this year he updated the figure, saying they had killed 622 people.

The RAB’s use of torture has also been exhaustively documented by human rights organisations. In addition, officers from the paramilitary force are alleged to have been involved in kidnap and extortion, and are frequently accused of taking large bribes in return for carrying out crossfire killings.

However, the cables reveal that both the British and the Americans, in their determination to strengthen counter-terrorism operations in Bangladesh, are in favour of bolstering the force, arguing that the “RAB enjoys a great deal of respect and admiration from a population scarred by decreasing law and order over the last decade”. In one cable, the US ambassador to Dhaka, James Moriarty, expresses the view that the RAB is the “enforcement organisation best positioned to one day become a Bangladeshi version of the US Federal Bureau of Investigation”.

In another cable, Moriarty quotes British officials as saying they have been “training RAB for 18 months in areas such as investigative interviewing techniques and rules of engagement”. Asked about the training assistance for the RAB, the Foreign Office said the UK government “provides a range of human rights assistance” in the country. However, the RAB’s head of training, Mejbah Uddin, told the Guardian that he was unaware of any human rights training since he was appointed last summer.

The cables make clear that British training for RAB officers began three years ago under the last Labour government.

However, RAB officials confirmed independently of the cables that they had taken part in a series of courses and workshops as recently as October, five months after the formation of the coalition government. Asked whether ministers had approved the training programme, the Foreign Office said only that William Hague, the foreign secretary, and other ministers, had been briefed on counter-terrorism spending.

Continue reading “WikiLeaks cables: Bangladeshi 'death squad' trained by UK government”

Soulscapes

The soul in question

Amirul Rajiv

Curator & Editor Soulscapes

Today, we are threatened by a drive towards a rigid social conformity and the struggle between differing conceptions of public morality and individual freedom. In this battleground the soul plays the role of a pawn. `Soulscapes? desperately seeks to explore these issues, beginning with an examination of society – the soul created and recreated ? and then moving through photographs and texts that consider the soul abused, objectified, discovered, aroused, desired, censored, mythologized, manipulated and celebrated. The images are corporeal, about the strengths, and vulnerabilities, of this most tangible manifestation of personal experience, ourselves, whether the soul in question is a child, a victim of suicide, a burning body or someone at the point of prostitution. Curating and editing might really be an instance of self-censorship, one of the most subtle and insidious assaults on literature and the arts. We hope that our audience will take this exhibition of `Soulscapes? to heart and mind at a moment when our souls are increasingly questioned and menaced.

Soulscapes

GMB Akash

With every picture you take, you enter a space that is unknown to you as a photographer. In the beginning it feels like forbidden territory, a place you are not supposed to enter surrounded by borders of privacy you are not supposed to cross. You, the photographer, are there at a factory, a old home or a brothel with your simple black bag hanging from your shoulder, eying everything around you as you are eyed by the people there. The first days following these intrusions I never take pictures because they would not be good. I wouldn’t know the people I met, wouldn’t understand the place I had just entered ? my photography would be stale and meaningless.

But there is always that moment when it feels completely natural to open that bag. And also there is no way of telling why it comes. Suddenly, I have a friendly conversation, or the afternoon light makes everybody around me relaxed and mellow, or someone looks at me in a trusting yet familiar way.

Then I take out my camera, and for me and everybody around me it is the most natural thing to do. There is consent. People don’t accuse me, or reject me or pose in unnatural ways. They are just there, doing what they normally do. Then I click away, and it feels like a conversation, a conversation between me and the people, between me and the location, between me and the light, between me and the souls that make this place alive. In such moments a landscape becomes a soulscape.

After such moments, life where I am working becomes trivial again, and the next day everybody asks for their photographs, and there is no difference if the people are girls from a brothel, children who work in a factory or farmers from the countryside.

But these little exchanges bring us closer to each other, and the ties between us, which started with small talk and conversation and continued with the first pictures I took, will become deeper and more meaningful, and so will the pictures I take.

And the closer I get to them and the deeper our friendship becomes, the simpler my photography gets. I am no longer looking for special angles or artistic points of views; I just open myself to these people, take a good look, frame and wait for the right moment. When I walk home, I have all the moments that I missed in my head, and they will become my source of inspiration in the days to come.

I see the beauty of people and the human soul in the pictures I take. And though the circumstances of some of the people I portray may be grim, back-breaking, depraved, the people themselves are always remarkable characters and souls. And it is my duty as a photographer and artist to point with my pictures at every aspect of existence in the society and world I live in, to show what can be shown, to go deep into every milieu and also into every aspect of poverty, deprivation and hardship that I encounter ? because the only sin for a photographer is to turn his head and look away.

Inaugural ceremony: Tuesday, 6 pm, 1 June 2010

Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts

Bengal Shilpalaya

House 275/F, Road 16 (new)

Sheikh Kamal Sarani

Dhanmandi, Dhaka 1209

The exhibition will remain open until 10 June 2010, daily from 12 – 8 pm

Salt Water Tears

photography by Munem Wasif text by Francis Hodgson plus an exclusive?audio interview about this project, plus?another short interviewabout his evolving style as a photographer. Every ecosystem has its fragile balance. That much we have already learnt. Scientists routinely now seek to document the excesses that will lead to imbalance, even where they can do nothing about them. And sometimes, just sometimes, legislation and implementation and eventually protection may follow. In the far south-west of Bangladesh, Munem Wasif shows us just what these abstract-sounding paradigms mean in practice. Nobody knows certainly why the water levels are changing in the Bay of Bengal, but they are. In a famously low-lying country, more and more people are under threat of catastrophic flooding. Coastal erosion, too, is accelerating, a matter of grave concern in a country where (under the pressure of population) every inch of usable land is at a premium. Munem Wasif found a region where changes to a single measurable fact ? salinity levels in the water table ? can be seen to have affected every part of the matrix of balances. Salinity has risen. The old agriculture is no longer possible because the old plants simply can?t grow. Shrimping ? a new industry ? has grown up, largely for export, using fewer workers and threatening the livelihood of many others. Shrimping in turn exposes more land to salt or brackish water. Farmers are reduced to occasional labour. Established structures of work and the societies centred on work change and break down. Many people have to venture into the mangrove swamps of the Sundarbans (a national park on the Indian side of the border, but not yet on the Bangladeshi) to fish or to collect roofing materials which used to be available closer to hand. In the Sundarbans they are exposed to a terrifying catalogue of risk, including attack from dog sharks, crocodiles, king cobras and the Bengal tiger. Women (it?s always the women) have to go ever farther in search of fresh water. New diseases become frequent, obviously connected to all these changes, but not yet provably so. So it goes on, a kaleidoscope of interconnected shifts, not fully understood, and not half predictable with accuracy. Munem Wasif has not gone to this blighted region to show us the abstractions of climate-change experts or the theories of macro-economists. Photography deals in the particular, and this project deals in the very particular. Wasif is himself Bangladeshi. Not for him the flak-jacket, the adrenaline rush, and five hours in the red zone. These are his people, although not quite in his part of the country. The accent is different but the language is shared. Wasif in fact rented a motorcycle to complete this commission, and when he tells you the names of the people in the pictures it?s because he met them and heard them, and knew them a little. The pictures, then, are almost by definition subjective. Too much ink has been spilt trying to work out when and whether photographers tell the truth. These pictures are absolutely personal to Wasif, absolutely his expression of his sentiments. But that doesn?t stop them being also a remarkable ? and true ? document of what is happening in the interplay of some of the complex of variables in this corner of Bangladesh. Photography reads big and small. Wasif shows you Johura Begum?s long arm reaching out to her husband as he dies of cancer of the liver, that simple tenderness is the only available healthcare in a village whose population are in desperate need. It?s a little tiny truth, certainly. The husband died, the woman lived on, widowed. The photographer was there, he knows. But it is also and at the same time a complex of many metaphors. There are many pictures like this because this scene has been played out so many times all over the world. It?s a picture ?about? infrastructure and financing, too, as well as morality and ethics. In another searing picture, containers of fresh water are dragged on foot in boats through clinging sterile mud. Shajhan Shiraj and his brothers from Gabura, we?re told, travel three hours in this kind of way every day. Stunted trees, clear water only in the distance, three men, three boats, and the keel-trail they etch in the mud. It?s not just a beautiful picture: the irony of boats travelling so painfully slowly by land with water as their only cargo is unimaginably painful. There is a powerful crossover in the way pictures work. Read these pictures only as little truths and they will wrench out your heart. Read them as big truths and they will drive you towards planning practical effort for change. you don?t need to know that Johura Begum?s husband was called Amer Chan to be moved to action by Wasif. We read about donor fatigue, compassion fatigue. Every viewer of these pictures will have at some point the sense of having seen them before. Salgado in the Sahel, just as shocking, maybe more. Very similar in feel and tonality. But it is not up to the photographers to provide us with new scenes. As long as those scenes are there and look the way they do, photographers will continue to show them to us. Some people will look at Wasif?s pictures here and call them derivative, and they?ll be right. But it isn?t fashion. There is not going to be a new length of trousers this season in the liver cancer business. Photographers can only do so much. If viewers are tired of being harrowed, tired of seeing these scenes one shouldn?t have to look at, perhaps we can understand that it?s the viewers who need to perk up their ideas, not the photographers. Munem Wasif, for one, is doing his bit. Now it?s up to us. ? Francis Hodgson Head of Photographs, Sotheby’s Chairman of Judges, Prix Pictet from the essay Munem Wasif: Tiny Truths, Big Truths Munem Wasif was shortlisted for the?Prix Pictet in 2008. As an integral element of the prize, Pictet decided to commission one of the shortlisted artists to record a water-related project. These photographs are the result. |

Coping With Life

Practical session under a banyan tree on the banks of the river Mahananda, Chapainawabgonj. ? Reza/Drik

Practical session under a banyan tree on the banks of the river Mahananda, Chapainawabgonj. ? Reza/Drik

?Kamera tulen?. Elsewhere, one would think a hundred times before pointing a camera. Permission, legality, issues of representation, all came into play. In any Bangladeshi village, getting people out of your lens is the problem. A cluster of heads surround the LCD. Peals of laughter. Old toothless smiles, a little baby held up so she can see. The disappointment of being left out. There might be serious issues to be dealt with, but right now being photographed was all that mattered.

Fourteen-year-old Rabeya, a member of our adolescent group, was taking photos in this beautiful location. I want everyone to live in such a beautiful environment. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Fatema Akter Hasi; 14

Fourteen-year-old Rabeya, a member of our adolescent group, was taking photos in this beautiful location. I want everyone to live in such a beautiful environment. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Fatema Akter Hasi; 14

Trainees from?Barguna. ? Jeevani Fernando

Trainees from?Barguna. ? Jeevani Fernando

With every intervention, one has concerns. Entering people?s lives, creating expectations, making friends, all have to deal with the disengagement that follows. It was people you were dealing with. How do you walk out of a life you have changed, perhaps forever? What do you leave behind, how much do you take away? These were difficult questions and we didn?t really have answers. But we?d tried it before, in cities and in villages. The remarkable transformations it had made to some children?s lives made the risk worth taking.

This is Shorifa Begum on her wedding day in Taherpur. She is a bride at eighteen years old. Shorifa did not want to get married. She stopped her education because she could not afford to continue it. Then her mother forced her to get married to a man who agreed to have a cheap wedding ceremony. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ??Morium Khatun; 16

This is Shorifa Begum on her wedding day in Taherpur. She is a bride at eighteen years old. Shorifa did not want to get married. She stopped her education because she could not afford to continue it. Then her mother forced her to get married to a man who agreed to have a cheap wedding ceremony. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ??Morium Khatun; 16

Md. Moinuddin training in Jamalpur. ? Aminuzzaman/Drik

Md. Moinuddin training in Jamalpur. ? Aminuzzaman/Drik

There were aesthetic concerns too. In talking of composition, rules of thirds, moments, balance, were we suppressing their spontaneity? Did we impinge upon their way of seeing? Were we erasing their natural ability to tell stories? We needn?t have worried. Sure, they tried things out. Pictures were created with remarkable composition. Balanced frames with well-placed elements formed stylised images that a trained photographer would have been proud of, but we had underestimated their instincts. Our fears of over intrusion were unfounded. The most striking images resulted not from our training, but because they had a voice. They could now tell their own stories and no one was going to get in their way, not even their teachers. The proud, chest-out, stiff at attention pose, that thwarted every photographer looking for something ?natural? was very much part of that expression. The loud coloured d?cor that would embarrass the urban genteel, was shown off with panache. Quirky images of everyday scenes, seen the way only children see, were the nuggets that glittered through our light box.

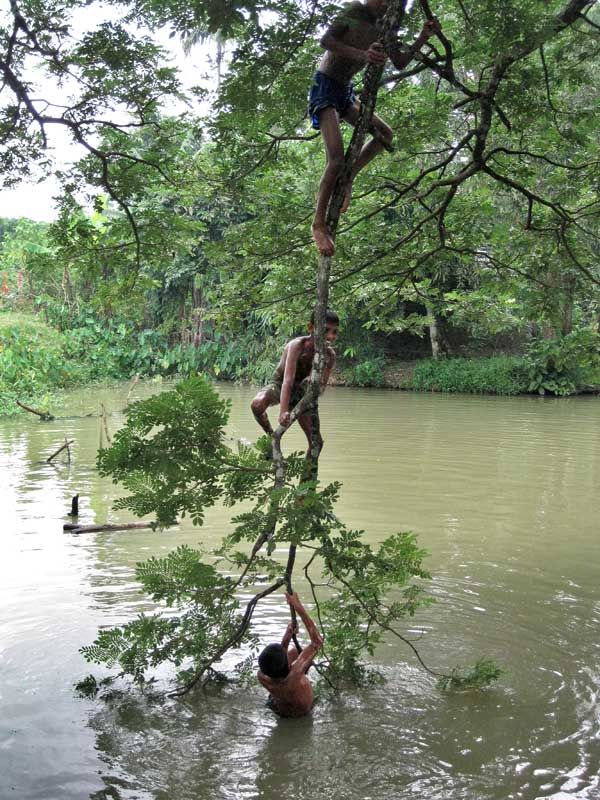

A group of children play in a local pond by climbing onto the tree and jumping into the water. They don’t go to school as their fathers are rickshaw pullers and do not earn enough to educate them. The parents are also not fully aware of the value of education. Barguna, 2009. ??Mohammad Jashim Uddin; 18

A group of children play in a local pond by climbing onto the tree and jumping into the water. They don’t go to school as their fathers are rickshaw pullers and do not earn enough to educate them. The parents are also not fully aware of the value of education. Barguna, 2009. ??Mohammad Jashim Uddin; 18

This is my uncle Shahidul’s goat. Every evening my uncle plays with the goat by holding up a leafy branch for him to jump up and eat. I watched this and took a photo. I also think that if the goat could become a human, then it might not need to jump like this. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ? Md. Sala-uddin Ahmed; 16

This is my uncle Shahidul’s goat. Every evening my uncle plays with the goat by holding up a leafy branch for him to jump up and eat. I watched this and took a photo. I also think that if the goat could become a human, then it might not need to jump like this. Chapainawabgonj, 2009. ? Md. Sala-uddin Ahmed; 16

There were quiet reflective moments too. Their realities, the every day challenges, the matter of factness with which they dealt with hurdles, had an immediacy that would humble a trained professional. Layered between romantic images in fields of Kash, looming clouds over flowing rivers, coiled branches silhouetted against stormy skies, were photographs that talked of strife. People less able who insisted on being able. Children longing to be children. A much too young bride. Another young mother to be, gingerly treading through a treacherous path. Absent are the images they were not allowed to show. That threatened a patriarchal society?s image. Pictures they had been forced to delete. Pictures they had staged, as their reality was being suppressed. To delete, to stage, to deal with censorship. These are things they hadn?t been taught. They were learning on the fly. Dealing with situations as best as they could. They were coping with life. Perhaps the ultimate lesson.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

This woman is removing paddy from the basket after it is boiled. She keeps her feet on a jute bag so that they don’t get burnt. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

This woman is removing paddy from the basket after it is boiled. She keeps her feet on a jute bag so that they don’t get burnt. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

Nature photographer. ? Reza/Drik

Nature photographer. ? Reza/Drik

Sohel, 12, lives in Nandina and works in Mostafa Bakery making biscuits and other snacks. He helps his family with his daily wages. It amazes me that a young boy like Sohel has to work for a living instead of going to school. I do not want any child to work for a living. We have to create awareness among people about child labour. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Md. Amir Hossain Apon; 14

Sohel, 12, lives in Nandina and works in Mostafa Bakery making biscuits and other snacks. He helps his family with his daily wages. It amazes me that a young boy like Sohel has to work for a living instead of going to school. I do not want any child to work for a living. We have to create awareness among people about child labour. Jamalpur, 2009. ? Md. Amir Hossain Apon; 14

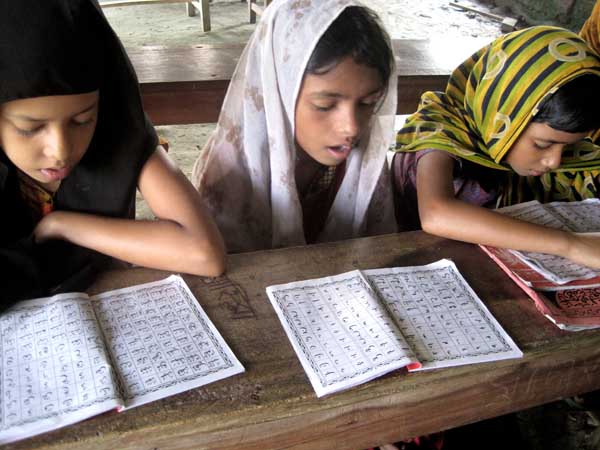

Amy and Rumi are 11 and 12 years old. They go to the madrasa to learn Arabic every morning. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

Amy and Rumi are 11 and 12 years old. They go to the madrasa to learn Arabic every morning. Barguna, 2009. ? Tania Islam Jhuma; 14

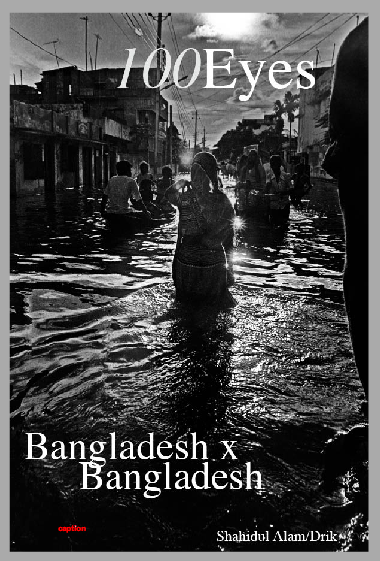

Bangladesh x Bangladesh

It was said to be the worst flood in one hundred years. As I walked down the flooded street leading to Kamlapur Railway Station in Dhaka, I was struck by the woman striding down the middle of the road. There was a studio on the left called “Dreamland Photographers” which was still open for business. It reminded me, that through it all, life goes on. Kamlapur. Dhaka. 2nd September 1988. Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

Climate change survivors.

?Tanvir Ahmed/drikNEWS

Bangladesh x Bangladesh

I discovered Bangladeshi photography in an unusual way. Like many people I spend too much time on Facebook, the social networking internet site that everyone seems addicted to. I have collected a large number of Facebook friends, many of them photographers from all over the world. Some I know and some I don?t After a few weeks on Facebook I started to get strange messages at the bottom of the screen popping up as live conversations, from photographers who wanted to talk. Some could barely type a word of English. They were awkward moments. I didn?t know what to say. It turned out that many of these little blips on my Facebook radar were from Bangladesh. This got me curious?there seemed to be quite a few photographers from Bangladesh. Checking the search engine Google for searches using the key words ?photo magazine? by geographic location showed that the leading source of the searches were coming from Bangladesh. Amazing.

This issue of 100eyes shows a country as seen through the eyes of its own photographers.?There is nothing remarkable about that, except in this case the country is one of the poorest nations in the world, known for being a subject for photojournalism rather than as a provider of photojournalists. Photographers flew into Bangadesh from New York, Paris, or London, that is, when they weren?t headed for nearby India. Photographers will still be flying to Bangladesh, including myself hopefully, but we?won?t be alone. In 1989 Bangladesh was depicted for Western eyes in a famous essay by photographer Sebastio Salgado that presented the shipbreaking yards at Chittagong. Twenty years later Bangladeshis are now behind the camera, and the results are stunning. One of the featured essays this month is ?Breaking Ships, Broken Men,? an essay by Saiful Huq Omi that looks at the same shipbreaking yards that Salgado photographed. Instead of reducing the workers to so many ants on a giant steel ant hill, Huq addresses the horrific conditions that the men work and live under?while retaining the atmospherics that made Salgado?s work so compelling twenty years before. Its fabulous work.

If there is a message in the emergence of ?indigenous photographers? it is that these photographers are able to achieve an intimacy with their subjects which enhances their humanity rather than objectifying and reducing the disadvantaged to stereotypical images of suffering. We are all too familiar with the pictures that accompany the campaigns of organizations responsible for feeding those who can not feed themselves. This imagery strips the impoverished of identity and renders the third world in one dimension? poor, and the result is more often than not that the poor stay that way.

As economically challenged as Bangladesh may be, there are 200 newspapers in the small country, and many of them are staffed by students from Pathshala, a school founded by Shahidul Alam, the central figure in the emergence of photography in Bangladesh, and the author of the cover image of this issue of 100Eyes. Alam developed into a photographer in Britain in the 1980?s after receiving a Doctorate in chemistry, and in 1989 started the Drik Picture Library and Pathshala, the South Asian Institute of Photography, the latter as part of a World Press Photo initiative. Most of the photographers showing work in this issue of 100Eyes went to Pathshala or taught there.

A traditional sanskrit world for ?center of learning,? Pathshala, according to Alam is???far more than teaching photography. It is about using the language of images to bring about social change. It is about nurturing minds and encouraging critical thinking. It is about responsible citizenship.?

He contines, ?In a land where textual literacy is low, it is about reaching out where words have failed. In a society where sleek advertising images construct our sense of values, studying at Pathshala is about challenging cultures of dominance.?

Alam and his fellow teachers, along with the World Press folks including Robert Pledge of Contact Press, have done a fantastic job. The students are exposed to classic photojournalism, poring over old issues of Life and National Geographic. Having spent hours going through the Drik archives I can testify to the training of the photographers? they always look for the single image that tells the whole story. I wondered to myself how there could be so many fortuitousy placed buildings in Bangladesh, as the Drik photographers seem able to find a high vantage point for every breaking news story. Abir Abdullah?s coverage of a horrific high rise fire in Dhaka, is as if he is almost one of the rescuers himself. Tanvir Ahmed is a very gifted photographer who seems able to move from news to features, and from color to black and white effortlessly. What can you say about Mumen Wasif? At 27 he is already working at the level of a Magnum photographer. I can?t say enough about all these photographers? they deserve attention and employment outside the confines of Bangladesh.

Inside Bangladesh the photographs carry the importance that Life Magazine stories had. And in a country where literacy is so low, as Shahidul Alam points out, ?what better way than pictures? of gaining understanding?

Looking at Bangladesh through the haze of the internet imakes me nostalgic for the time when photojournalism mattered, When people opened their weekly copies of Life or Time Magazine and looked to photographers to show them what was happening in their country and the world. At that time it seemed as though photography could really make a difference? and that time was not that long ago. I was one of those photographers.

I get a similar sense when I look at the work of the Pathshala photographers? that their work is not just for the vacumn of the internet, meant only for other photographers to admire, or rendered ?modern? and fit only for curation and the gallery wall. Far from it, their work has relevance and a purpose within their own country, which may be underdeveloped in some ways, but seems progressive in others.

There are huge problems ahead for Bangladesh. Overpopulation, an enormous burden of poverty in mouths that the country itself can not feed, energy dependence, and the ravages of the monsoons combined with the floodwaters from the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta, all these problems are facing a country with limited ability to develop on its own, But one thing is for certain? whatever happens in Bangladesh will be well photographed

?Andy Levin/New Orleans. Louisiana

Bangladesh, standing on the edge

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Preface?by Christian Caujolle

Expressions, hands, faces, presence and pain, tenderness and anxiety, light and encounters, questions and determination as well as a thousand other things run through Munem Wasif‘s photographs.

The way Wasif takes his photographs can be summed up into two ways: people and the frame. He definitely belongs to a humanist tradition, contemporary in content for the attention he gives to people and to the way they live, what they have to endure and all they bear in today’s pitiless world, disrupted, torn by drastic climatic changes and economic speculation. A world where speed is queen and profit king inconsiderately leaving on the wayside the rejected that it spawns. It is salutary that an eye such as Wasif’s reminds us that these things exist, that there are men, women, children, “little people” like us who have to withstand much more than we do.

In photography, the approach and the representation of suffering and exclusion are often entangled in a jumble of good intentions, generous in intention, they call for tearful compassion, with clich?d images that end up making us weary, forever repeating themselves, they end up by?anaesthetising?our capacity to react. Wasif produces the opposite effect. He makes us question and makes us concerned.

This is done with so little and at the same time goes to the essential. We can not doubt his commitment to those he photographs, the excluded, the victims, panic-stricken by a world ruled by the race for profit and blinded by immediate return based on solely commercial value. He puts this world into form, radical in its description, he imposes it and gives it to us to see clearly.

This is where the frame comes in. A way of focusing in on the world, to sum it up in a series of specific points of view, classic in their composition, forcing us to see and to perceive their intention.

Munem Wasif‘s frames are clean-cut, precise, almost cold. Without flourish. He asks us to look, to perceive, to take a stand. Therefore to act.

—————————

Wasif’s work will be shown at Visa Pour la Image at Perpignan. He won the?City of Perpignan Young Reporter?s Award for 2008. He graduated from Pathshala, The South Asian Institute of Photography, and works at DrikNews. His work is represented by Agence VU and Majority World.

Another View

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Lucia Chiriboga portrays the deep spirituality in Ecuadorian life. Long before Photoshop became commonplace, Lucia began creating complex images by subtle multiple exposures, as a way of weaving multilayered stories of her ancestors. ? Lucia Chiriboga/Drik/Majority World

It was a grand opening. The ?Who?s Who? of development in Britain was there, championing the noble cause ? the Millennium Development Goals, making poverty history.

The Bob Geldof circus could perhaps be pardoned. Geldof is neither a development worker nor someone particularly knowledgeable about the subject. But for the organizers of the ?bash? at the OXO Tower on London?s South Bank to produce such a culturally insensitive event was revealing.

Apart from parading a few young black people from Africa, who extolled the virtues of ?development?, there was little contribution from the Majority World. The key speakers, typically white Western development workers, spoke of the role that they were playing in saving the poor of the Global South. The token dark-skinned people, having played their part, were soon forgotten.

The centrepiece of this celebration was an exhibition entitled Eight Ways to Change the World. All the photographs were taken by white Western photographers. No-one questioned the implication of such an exercise. When I confronted one of the organizers he explained that the curator ? a director of a Western photographic agency ? had decided not to use Majority World photographers because they ?didn?t have the eye?. The sophisticated visual language possessed by the Western audience was presumably beyond the capacity of a photographer from the South to comprehend, let alone engage with at a creative level.

New rules

This represents a shift from the position of 20 years ago when we started asking why Majority World photographers were not being used by mainstream media and development agencies. The answer then had been: ?They don?t exist.? Today our existence is difficult to deny. The internet; the fact that several Majority World agencies operate successfully; and that photographers belonging to such agencies regularly win international awards: all these things mean we are no longer invisible.

Now it?s a different set of rules. We have to prove we have the eye. A similar statement about blacks, women, or minority groups of any sort, would raise a storm. But when such prejudice is used against a group of media professionals from the South, who happen to represent the majority of humankind, no-one appears to bat an eyelid.

I have, of course, faced this situation before. There was, for example, a fax from the National Geographic Society Television Division asking if we could help them with the production of a film that would include the Bangladeshi cyclone of 1991. They wanted specific help in locating ?US, European or UN people… who would lead us to a suitable Bangladeshi family?. The irony of making such a request to a picture agency dedicated to promoting local voices had obviously escaped them. We had gotten used to requests for iconic objects of poverty that international NGOs insisted existed in abundance and had to be photographed ? but which locals neither knew nor had heard of.

The economics of suffering

Charities and development agencies need to raise money from the Western public. The best way to pull the heart strings ? and thereby the purse strings ? is to show those doleful eyes of the disadvantaged.

Perhaps photographers from the South cannot be trusted to understand this. Perhaps they are so hardened to such images of daily suffering that they are unable to appreciate the impact these sights might have on Western audiences ? and the coffers of Western aid agencies.

But certain changes have been taking place, forcing various adjustments. Media budgets have become tighter than they were. Flying people to distant locations is expensive. Having Western photographers ?on the ground? can be dangerous in some cases ? and costly in terms of insurance premiums. Better to have locals in the firing line. So, slowly, local names have begun to creep in. Certain rules still apply of course, such as the vast differentials in pay between local and Western photographers.

Stories about Nike regularly make the headlines, but the exploitative terms on which local photographers work rarely surface. The Bangla saying ?kaker mangsho kak khai na? (a crow doesn?t eat crow?s meat) seems to apply to journalism: criticism of the media is taboo. Not only do the workers on the media sweatshops have to work for peanuts, they need to know which stories to tell. None of this journalistic independence rubbish: gimme stories that sell.

This, of course, affects Southern photographers. When they know certain stories sell, they themselves begin to supply the ?appropriate? images. A man known to carry a toy gun in the streets of Dhaka is repeatedly photographed at religious rallies, and despite common knowledge that it is a fake gun, news agencies run the picture without explaining the nature of the situation. Numerous wire photographers have been known to stage flood pictures and in one famous instance, a child was shown to be swimming to safety in what was known to be knee deep water. The photograph went on to win a major press award.

Money also affects publishers. Smaller budgets require careful shopping. The Corbis, Getty and Reuters image supermarkets are rapidly squeezing out the ?corner store? suppliers and a small Majority World picture library simply can?t compete.

But there are other factors in the equation. Development isn?t simply about money. What about developing mutual respect; enabling equitable partnerships; providing enabling environments for intellectual exchange? What about creating awareness of the underlying causes of poverty? These are all integral parts of the development process. When all things are added up, cheap images providing clich?d messages do more harm than good. They do not address the crucial issue: poverty is almost always a product of exploitation, at local, regional and international levels. If poverty is simply addressed in terms of what people lack in monetary terms, then the more important issues of exploitation are sidelined.

Materially poor nations should have a say in how they are represented. This picture, taken in the early days of the Maoist movement, by Nepalese photographer Binod Dhungel, shows members of his country?s Maoist Movement long before it was breaking news. ? Binod Dhungel/Drik/Majority World

A broader picture

However, the type of imagery required from the Majority World is broadening. This is coming less from growing political sensibility and more from global economic shifts. Negative imagery is seen as a deterrent to foreign investment in emerging markets. With transnationals interested in cheap labour, and a wider consumer base, a different profile is now required to stimulate investor confidence. So, along with the standard fare of flood and famine, there are stories of Indian and Chinese billionaires and how they have benefited from capitalism.

Furthermore the new ?inclusive? media now take on more ethnic-minority journalists. But when they come over to do their groundbreaking stories, it is the rookie on the streets of Dhaka who provides the leads, conducts the research, translates, drives, fixes, and does all that is necessary for the story to emerge. If things do go wrong ? as when Britain?s Channel 4 TV attempted an ill-fated expos? in Bangladesh in late 2002 ? the Western journalists are likely to be home for Christmas while the local fixers face torture in jail.

Drik?s vision

Lacking the advantages of our Western counterparts, image-makers in the South have had to rely on ingenuity and making-do in order to move from being fixers to being authors in their own right. We have had to be pioneers. With one filing cabinet, an XT computer without a hard drive, and a converted toilet as a darkroom, we decided we would take on the established rich-world photo agencies. On 4 September 1989 Drik Alokchitra Granthagar was set up in Dhaka.

The Sanskrit word Drik means vision, inner vision, and philosophy of vision. That vision of a more egalitarian world, where materially poor nations have a say in how they are represented, remains our driving force.

The European agencies I had encountered wanted a minimum submission of 300 transparencies and told you not to ask for money for the first three years. This constituted a massive investment for a Majority World photographer, and virtually ruled out her entry into the market. We had a very different approach. If a photographer had a single good image which we felt needed to be seen we would take her on, try and sell the picture and pay her as soon as the money came in.

It allowed the photographer to buy more rolls of film and carry on working. The photographers didn?t have printing and developing facilities so we set up a good quality darkroom and trained people to make high quality prints. They had no lights so we set up a studio.

The only gallery spaces available were owned by the State or foreign cultural missions, none of which would show controversial work. So we built our own galleries. Few would publish pictures well so we built our own pre-press unit and published postcards, bookmarks and calendars which we sold door-to-door to pay for running costs.

Photography was largely male-dominated, so we organized workshops for women photographers. There were no working-class people in the media, so we started training poor children in photography. We couldn?t afford faxes or international phone calls, so we set up Bangladesh?s first email service and lobbied for the introduction of fully fledged internet. Professor Yunus, the Nobel Prize winner, was our first user. We set up electronic bulletin boards on issues important to us, such as child rights and environmental issues.

We started putting together a database of photographers in the South, and wrote off to as many organizations as we could, offering our services. No-one replied. Undeterred, we put together a portfolio of black-and-white prints, largely by Bangladeshi photographers.

On a rare visit to Europe, I visited the office of the New Internationalist in Oxford. Dexter Tiranti greeted me warmly. He had received our letter, but hadn?t given it too much importance. An agency in Bangladesh seemed too far distant for the NI to work with on a regular basis. Having seen the portfolio, however, Dexter sat me down at his desk and started ringing picture users across Europe. I remember feeling envious of this ability simply to pick up a phone and call someone in another country, but was grateful for the contacts. Dexter asked us to submit pictures for the NI Almanac. The next year we got a letter from him that stated: ?The photographs are beautiful and the reason we are using only six is because we can?t really have too many from one country.? Others Dexter had phoned that day, and many others we have contacted since, have responded similarly, and so picture sales slowly grew ? but it was no easy ride.

Drik?s email network was put to use when writer and feminist Taslima Nasrin, pictured here in hiding, was being persecuted. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

Knife wounds and death threats

Our problems weren?t simply ones of surviving on slender means and competing against agencies based in London, Paris and New York. Our activism created problems on our home soil too. We had, by then, set up our own website and had helped to establish the first webzine and internet portal in the country. Our email network had been put to use when Taslima Nasrin was being persecuted. The website became the seat of resistance when pro-government thugs committed rape in a university campus. So the site, and later the agency, came under attack.

The day after our human rights portal www.banglarights.net was launched, all the telephone lines of the agency were disconnected. It took us twoand- a-half years to get the lines back, but that never stopped our internet service and we stayed connected. Later, Drik became the seat of resistance when the Government used the military to round up opposition activists. I was attacked on the street, during curfew and in a street protected by the military. I received eight knife wounds.

So we learnt to walk a fine line.

It wasn?t just the Government that found us unpalatable. The US embassy felt it couldn?t work with us because we opposed President Clinton?s visit to Bangladesh.

Letter by John Kinkannon (director of USIA in Bangladesh) to Mayeen Ahmed, coordinator of Chobi Mela (2000).

The British Council demanded we take down a show that talked about colonialism, and threatened that future projects might be jeopardized when we openly opposed the invasion of Iraq. Death threats, some real, some less serious and a whole range of sabotage attempts have been part of the path we?ve travelled.

Current strategies are more subtle. We know we will never be given work by certain agencies and that visas for some of us will be more difficult to get, but it is certainly not all negative. The main strength of Drik has been its friends and their support. None of what we have achieved would have been possible without the contribution of a large number of people, ranging from ordinary Bangladeshis who have rallied when it mattered, to influential people thousands of miles away who have provided moral and material support. Combining our compulsion to be socially effective with the requirement to be financially independent has remained our biggest challenge. It is a difficult balancing act.

A great high

Taking a principled position has other drawbacks. People work long hours for salaries below the industry norm. There are few perks. But working at Drik is a special experience; a great high. Not everyone can survive on these highs, of course, and job satisfaction doesn?t help pay the bills, so we need to be competitive and ensure a level of quality so that we can hold our own despite the political pressures.

Eighteen years down the road, we now have a workforce of around 60. Graduates from our school of photography, Pathshala, hold senior positions in major publications. The working-class children we?ve trained have gone on to win Emmys and other awards, and I believe Majority World photographers feel they have a platform.

The big agencies like Reuters and Getty can provide images at a cost and a speed impossible for independent practitioners to match, a very real consideration for picture editors under time pressure and working to tight budgets. The fact that Corbis (owned by Microsoft) is buying up picture archives like the Bettman is important for their preservation, but the images that now exist 200 feet below the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania are no longer accessible to the students, scholars and researchers. An important part of our visual history is now in the control of one person ? Bill Gates.

Golam Kasem (nicknamed Daddy) was Drik?s oldest photographer when he died at the age of 103. His original glass plates date back to 1918. This 1927 image is one of many where Daddy records everyday life in rich detail. ? Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

Fair trade

Father Paul Casperg, who has been working for many years with the tea plantation workers in Kandy, has an interesting story to tell. Nearly 30 years ago, in his Masters thesis at the London School of Economics, Father Casperg was able to show that an increase of two pence (four US cents) in the price of a cup of tea being sold on the British railways would, providing it went to the Kandy tea plantation workers, result in more income than the total foreign aid received by the Sri Lankan Government.

Father Casperg rightly concluded that it was fair trade that Sri Lanka needed, not more aid.

That is what fair trade imagery organizations like majorityworld.com and kijijiVision (see Action) are trying to do. By invoking ethical standards in the trading of images, these organizations address not only the distorted and disrespectful depiction of people of the Global South, but also the economic divide.

Organizations that call for Majority World governments to be more transparent and accountable need to reflect upon their own ethical standards when it comes to depicting and dealing with the South. Practices such as not allowing photographers to retain copyright or film are justified by the ?convenience? of distributing images. Such ?convenience clauses? are rarely applied to Western photographers, who know the law and can exercise their rights.

Light, flexible, potent

We are resisting, though. The new portal, majorityworld.com, supported strongly by its lobbying partner kijijiVision.org, has built on the extended groundwork done by Drik. DrikNews.com, though still very young, threatens to give the wire agencies a run for their money, and photographers in the South are pooling their resources, including developing close partnerships with like-minded Western organizations.

Recently, I was sitting with a small group of photographers, painters and filmmakers in a corner of the top-floor gallery of the Voluntary Artists Society of Thimpu (capital of Bhutan). At the end of the showing of a film on Chobi Mela IV ? the festival of photography in Asia ? projected on a bedsheet pinned on the gallery wall, the conversation veered to pooling resources in neighbouring countries. Sharing computers, scanners, and contacts, we talked of bus routes to neighbouring countries, and finding public spaces for showing work. What we needed was an online solution that would serve all Majority World photographers.

Having purchased expensive software produced in the West for selling pictures online, we were further bled by consultancy fees we had to pay every time we needed to adapt it to our situation. So, eventually, we developed our own software. It is an inexpensive but highly efficient search engine that local newspaper archives can use. Developed using largely open-source modules, it is constantly updated based on feedback from users from all over the globe and it has worked well on low bandwidth.

Groups in Bhutan, Peru, Tanzania and Vietnam recognize that the wire services and the big agencies have a different agenda. If it?s a guerrilla war against the corporations that has to be fought, then we need different tools. Light, flexible, inexpensive and potent ones.

A revolution is taking place. As new names creep into the byline, unfamiliar faces step up to the award podium and fresh imagery ? vibrant, questioning and revealing ? makes it into mainstream media, a whole new world is opening up. A Majority World.

Originally published in the New Internationalist Magazine in August 2007

Image take-over

In the 1990s independent picture libraries and agencies disappeared at an alarming rate as they were absorbed or driven out of business by larger ones. Dominating the field was Corbis, created by Microsoft Corp founder Bill Gates. Corbis now has 24 offices in 16 countries, represents some 29,000 photographers and controls around 100 million images. Last year it acquired the Australian Picture Library, entered a partnership with IndiaPicture.com and opened a new office in Beijing. Its 2006 revenue was more than $251 million.

Other big players have included Getty Images, founded in 1995, which now has 20 offices worldwide and controls over one million images. Jupiterimages, a division of the Connecticut-based Jupitermedia Corporation, manages over seven million images online, while Reuters has an archive of over two million images.

In recent years the microstock photography industry, led by iStockPhoto and later ShutterStock, Dreamstime, Fotolia, and BigStockPhoto has emerged as a rapidly growing market. Using the internet as their sole distribution method, and recruiting mainly amateur and hobbyist photographers from around the globe, these companies are able to offer stock libraries of pictures at very low prices. Corporate giants Corbis, Getty and Jupiterimages have now muscled their way into this market too, adding to their everexpanding fortfolio of the world?s imagery.