Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Lucia Chiriboga portrays the deep spirituality in Ecuadorian life. Long before Photoshop became commonplace, Lucia began creating complex images by subtle multiple exposures, as a way of weaving multilayered stories of her ancestors. ? Lucia Chiriboga/Drik/Majority World

It was a grand opening. The ?Who?s Who? of development in Britain was there, championing the noble cause ? the Millennium Development Goals, making poverty history.

The Bob Geldof circus could perhaps be pardoned. Geldof is neither a development worker nor someone particularly knowledgeable about the subject. But for the organizers of the ?bash? at the OXO Tower on London?s South Bank to produce such a culturally insensitive event was revealing.

Apart from parading a few young black people from Africa, who extolled the virtues of ?development?, there was little contribution from the Majority World. The key speakers, typically white Western development workers, spoke of the role that they were playing in saving the poor of the Global South. The token dark-skinned people, having played their part, were soon forgotten.

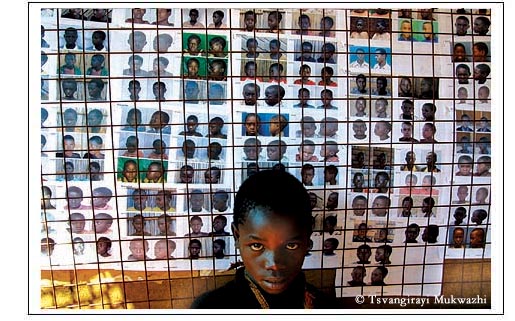

The centrepiece of this celebration was an exhibition entitled Eight Ways to Change the World. All the photographs were taken by white Western photographers. No-one questioned the implication of such an exercise. When I confronted one of the organizers he explained that the curator ? a director of a Western photographic agency ? had decided not to use Majority World photographers because they ?didn?t have the eye?. The sophisticated visual language possessed by the Western audience was presumably beyond the capacity of a photographer from the South to comprehend, let alone engage with at a creative level.

New rules

This represents a shift from the position of 20 years ago when we started asking why Majority World photographers were not being used by mainstream media and development agencies. The answer then had been: ?They don?t exist.? Today our existence is difficult to deny. The internet; the fact that several Majority World agencies operate successfully; and that photographers belonging to such agencies regularly win international awards: all these things mean we are no longer invisible.

Now it?s a different set of rules. We have to prove we have the eye. A similar statement about blacks, women, or minority groups of any sort, would raise a storm. But when such prejudice is used against a group of media professionals from the South, who happen to represent the majority of humankind, no-one appears to bat an eyelid.

I have, of course, faced this situation before. There was, for example, a fax from the National Geographic Society Television Division asking if we could help them with the production of a film that would include the Bangladeshi cyclone of 1991. They wanted specific help in locating ?US, European or UN people… who would lead us to a suitable Bangladeshi family?. The irony of making such a request to a picture agency dedicated to promoting local voices had obviously escaped them. We had gotten used to requests for iconic objects of poverty that international NGOs insisted existed in abundance and had to be photographed ? but which locals neither knew nor had heard of.

The economics of suffering

Charities and development agencies need to raise money from the Western public. The best way to pull the heart strings ? and thereby the purse strings ? is to show those doleful eyes of the disadvantaged.

Perhaps photographers from the South cannot be trusted to understand this. Perhaps they are so hardened to such images of daily suffering that they are unable to appreciate the impact these sights might have on Western audiences ? and the coffers of Western aid agencies.

But certain changes have been taking place, forcing various adjustments. Media budgets have become tighter than they were. Flying people to distant locations is expensive. Having Western photographers ?on the ground? can be dangerous in some cases ? and costly in terms of insurance premiums. Better to have locals in the firing line. So, slowly, local names have begun to creep in. Certain rules still apply of course, such as the vast differentials in pay between local and Western photographers.

Stories about Nike regularly make the headlines, but the exploitative terms on which local photographers work rarely surface. The Bangla saying ?kaker mangsho kak khai na? (a crow doesn?t eat crow?s meat) seems to apply to journalism: criticism of the media is taboo. Not only do the workers on the media sweatshops have to work for peanuts, they need to know which stories to tell. None of this journalistic independence rubbish: gimme stories that sell.

This, of course, affects Southern photographers. When they know certain stories sell, they themselves begin to supply the ?appropriate? images. A man known to carry a toy gun in the streets of Dhaka is repeatedly photographed at religious rallies, and despite common knowledge that it is a fake gun, news agencies run the picture without explaining the nature of the situation. Numerous wire photographers have been known to stage flood pictures and in one famous instance, a child was shown to be swimming to safety in what was known to be knee deep water. The photograph went on to win a major press award.

Money also affects publishers. Smaller budgets require careful shopping. The Corbis, Getty and Reuters image supermarkets are rapidly squeezing out the ?corner store? suppliers and a small Majority World picture library simply can?t compete.

But there are other factors in the equation. Development isn?t simply about money. What about developing mutual respect; enabling equitable partnerships; providing enabling environments for intellectual exchange? What about creating awareness of the underlying causes of poverty? These are all integral parts of the development process. When all things are added up, cheap images providing clich?d messages do more harm than good. They do not address the crucial issue: poverty is almost always a product of exploitation, at local, regional and international levels. If poverty is simply addressed in terms of what people lack in monetary terms, then the more important issues of exploitation are sidelined.

Materially poor nations should have a say in how they are represented. This picture, taken in the early days of the Maoist movement, by Nepalese photographer Binod Dhungel, shows members of his country?s Maoist Movement long before it was breaking news. ? Binod Dhungel/Drik/Majority World

A broader picture

However, the type of imagery required from the Majority World is broadening. This is coming less from growing political sensibility and more from global economic shifts. Negative imagery is seen as a deterrent to foreign investment in emerging markets. With transnationals interested in cheap labour, and a wider consumer base, a different profile is now required to stimulate investor confidence. So, along with the standard fare of flood and famine, there are stories of Indian and Chinese billionaires and how they have benefited from capitalism.

Furthermore the new ?inclusive? media now take on more ethnic-minority journalists. But when they come over to do their groundbreaking stories, it is the rookie on the streets of Dhaka who provides the leads, conducts the research, translates, drives, fixes, and does all that is necessary for the story to emerge. If things do go wrong ? as when Britain?s Channel 4 TV attempted an ill-fated expos? in Bangladesh in late 2002 ? the Western journalists are likely to be home for Christmas while the local fixers face torture in jail.

Drik?s vision

Lacking the advantages of our Western counterparts, image-makers in the South have had to rely on ingenuity and making-do in order to move from being fixers to being authors in their own right. We have had to be pioneers. With one filing cabinet, an XT computer without a hard drive, and a converted toilet as a darkroom, we decided we would take on the established rich-world photo agencies. On 4 September 1989 Drik Alokchitra Granthagar was set up in Dhaka.

The Sanskrit word Drik means vision, inner vision, and philosophy of vision. That vision of a more egalitarian world, where materially poor nations have a say in how they are represented, remains our driving force.

The European agencies I had encountered wanted a minimum submission of 300 transparencies and told you not to ask for money for the first three years. This constituted a massive investment for a Majority World photographer, and virtually ruled out her entry into the market. We had a very different approach. If a photographer had a single good image which we felt needed to be seen we would take her on, try and sell the picture and pay her as soon as the money came in.

It allowed the photographer to buy more rolls of film and carry on working. The photographers didn?t have printing and developing facilities so we set up a good quality darkroom and trained people to make high quality prints. They had no lights so we set up a studio.

The only gallery spaces available were owned by the State or foreign cultural missions, none of which would show controversial work. So we built our own galleries. Few would publish pictures well so we built our own pre-press unit and published postcards, bookmarks and calendars which we sold door-to-door to pay for running costs.

Photography was largely male-dominated, so we organized workshops for women photographers. There were no working-class people in the media, so we started training poor children in photography. We couldn?t afford faxes or international phone calls, so we set up Bangladesh?s first email service and lobbied for the introduction of fully fledged internet. Professor Yunus, the Nobel Prize winner, was our first user. We set up electronic bulletin boards on issues important to us, such as child rights and environmental issues.

We started putting together a database of photographers in the South, and wrote off to as many organizations as we could, offering our services. No-one replied. Undeterred, we put together a portfolio of black-and-white prints, largely by Bangladeshi photographers.

On a rare visit to Europe, I visited the office of the New Internationalist in Oxford. Dexter Tiranti greeted me warmly. He had received our letter, but hadn?t given it too much importance. An agency in Bangladesh seemed too far distant for the NI to work with on a regular basis. Having seen the portfolio, however, Dexter sat me down at his desk and started ringing picture users across Europe. I remember feeling envious of this ability simply to pick up a phone and call someone in another country, but was grateful for the contacts. Dexter asked us to submit pictures for the NI Almanac. The next year we got a letter from him that stated: ?The photographs are beautiful and the reason we are using only six is because we can?t really have too many from one country.? Others Dexter had phoned that day, and many others we have contacted since, have responded similarly, and so picture sales slowly grew ? but it was no easy ride.

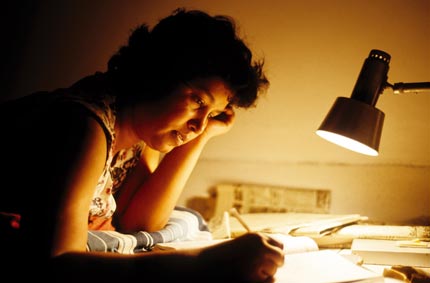

Drik?s email network was put to use when writer and feminist Taslima Nasrin, pictured here in hiding, was being persecuted. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

Knife wounds and death threats

Our problems weren?t simply ones of surviving on slender means and competing against agencies based in London, Paris and New York. Our activism created problems on our home soil too. We had, by then, set up our own website and had helped to establish the first webzine and internet portal in the country. Our email network had been put to use when Taslima Nasrin was being persecuted. The website became the seat of resistance when pro-government thugs committed rape in a university campus. So the site, and later the agency, came under attack.

The day after our human rights portal www.banglarights.net was launched, all the telephone lines of the agency were disconnected. It took us twoand- a-half years to get the lines back, but that never stopped our internet service and we stayed connected. Later, Drik became the seat of resistance when the Government used the military to round up opposition activists. I was attacked on the street, during curfew and in a street protected by the military. I received eight knife wounds.

So we learnt to walk a fine line.

It wasn?t just the Government that found us unpalatable. The US embassy felt it couldn?t work with us because we opposed President Clinton?s visit to Bangladesh.

Letter by John Kinkannon (director of USIA in Bangladesh) to Mayeen Ahmed, coordinator of Chobi Mela (2000).

The British Council demanded we take down a show that talked about colonialism, and threatened that future projects might be jeopardized when we openly opposed the invasion of Iraq. Death threats, some real, some less serious and a whole range of sabotage attempts have been part of the path we?ve travelled.

Current strategies are more subtle. We know we will never be given work by certain agencies and that visas for some of us will be more difficult to get, but it is certainly not all negative. The main strength of Drik has been its friends and their support. None of what we have achieved would have been possible without the contribution of a large number of people, ranging from ordinary Bangladeshis who have rallied when it mattered, to influential people thousands of miles away who have provided moral and material support. Combining our compulsion to be socially effective with the requirement to be financially independent has remained our biggest challenge. It is a difficult balancing act.

A great high

Taking a principled position has other drawbacks. People work long hours for salaries below the industry norm. There are few perks. But working at Drik is a special experience; a great high. Not everyone can survive on these highs, of course, and job satisfaction doesn?t help pay the bills, so we need to be competitive and ensure a level of quality so that we can hold our own despite the political pressures.

Eighteen years down the road, we now have a workforce of around 60. Graduates from our school of photography, Pathshala, hold senior positions in major publications. The working-class children we?ve trained have gone on to win Emmys and other awards, and I believe Majority World photographers feel they have a platform.

The big agencies like Reuters and Getty can provide images at a cost and a speed impossible for independent practitioners to match, a very real consideration for picture editors under time pressure and working to tight budgets. The fact that Corbis (owned by Microsoft) is buying up picture archives like the Bettman is important for their preservation, but the images that now exist 200 feet below the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania are no longer accessible to the students, scholars and researchers. An important part of our visual history is now in the control of one person ? Bill Gates.

Golam Kasem (nicknamed Daddy) was Drik?s oldest photographer when he died at the age of 103. His original glass plates date back to 1918. This 1927 image is one of many where Daddy records everyday life in rich detail. ? Golam Kasem/Drik/Majority World

Fair trade

Father Paul Casperg, who has been working for many years with the tea plantation workers in Kandy, has an interesting story to tell. Nearly 30 years ago, in his Masters thesis at the London School of Economics, Father Casperg was able to show that an increase of two pence (four US cents) in the price of a cup of tea being sold on the British railways would, providing it went to the Kandy tea plantation workers, result in more income than the total foreign aid received by the Sri Lankan Government.

Father Casperg rightly concluded that it was fair trade that Sri Lanka needed, not more aid.

That is what fair trade imagery organizations like majorityworld.com and kijijiVision (see Action) are trying to do. By invoking ethical standards in the trading of images, these organizations address not only the distorted and disrespectful depiction of people of the Global South, but also the economic divide.

Organizations that call for Majority World governments to be more transparent and accountable need to reflect upon their own ethical standards when it comes to depicting and dealing with the South. Practices such as not allowing photographers to retain copyright or film are justified by the ?convenience? of distributing images. Such ?convenience clauses? are rarely applied to Western photographers, who know the law and can exercise their rights.

Light, flexible, potent

We are resisting, though. The new portal, majorityworld.com, supported strongly by its lobbying partner kijijiVision.org, has built on the extended groundwork done by Drik. DrikNews.com, though still very young, threatens to give the wire agencies a run for their money, and photographers in the South are pooling their resources, including developing close partnerships with like-minded Western organizations.

Recently, I was sitting with a small group of photographers, painters and filmmakers in a corner of the top-floor gallery of the Voluntary Artists Society of Thimpu (capital of Bhutan). At the end of the showing of a film on Chobi Mela IV ? the festival of photography in Asia ? projected on a bedsheet pinned on the gallery wall, the conversation veered to pooling resources in neighbouring countries. Sharing computers, scanners, and contacts, we talked of bus routes to neighbouring countries, and finding public spaces for showing work. What we needed was an online solution that would serve all Majority World photographers.

Having purchased expensive software produced in the West for selling pictures online, we were further bled by consultancy fees we had to pay every time we needed to adapt it to our situation. So, eventually, we developed our own software. It is an inexpensive but highly efficient search engine that local newspaper archives can use. Developed using largely open-source modules, it is constantly updated based on feedback from users from all over the globe and it has worked well on low bandwidth.

Groups in Bhutan, Peru, Tanzania and Vietnam recognize that the wire services and the big agencies have a different agenda. If it?s a guerrilla war against the corporations that has to be fought, then we need different tools. Light, flexible, inexpensive and potent ones.

A revolution is taking place. As new names creep into the byline, unfamiliar faces step up to the award podium and fresh imagery ? vibrant, questioning and revealing ? makes it into mainstream media, a whole new world is opening up. A Majority World.

Originally published in the New Internationalist Magazine in August 2007

Image take-over

In the 1990s independent picture libraries and agencies disappeared at an alarming rate as they were absorbed or driven out of business by larger ones. Dominating the field was Corbis, created by Microsoft Corp founder Bill Gates. Corbis now has 24 offices in 16 countries, represents some 29,000 photographers and controls around 100 million images. Last year it acquired the Australian Picture Library, entered a partnership with IndiaPicture.com and opened a new office in Beijing. Its 2006 revenue was more than $251 million.

Other big players have included Getty Images, founded in 1995, which now has 20 offices worldwide and controls over one million images. Jupiterimages, a division of the Connecticut-based Jupitermedia Corporation, manages over seven million images online, while Reuters has an archive of over two million images.

In recent years the microstock photography industry, led by iStockPhoto and later ShutterStock, Dreamstime, Fotolia, and BigStockPhoto has emerged as a rapidly growing market. Using the internet as their sole distribution method, and recruiting mainly amateur and hobbyist photographers from around the globe, these companies are able to offer stock libraries of pictures at very low prices. Corporate giants Corbis, Getty and Jupiterimages have now muscled their way into this market too, adding to their everexpanding fortfolio of the world?s imagery.