Tag: health

The Imperial Mind

American rage at Pakistan over the punishment of a CIA-cooperating Pakistani doctor is quite revealing

BY?GLENN GREENWALD

SATURDAY, MAY 26, 2012 05:53 PM BDT

Americans of all types ? are just livid that a Pakistani tribal court (reportedly in consultation with Pakistani officials) has?imposed?a 33-year prison sentence on Shakil Afridi, the Pakistani physician who secretly worked with the CIA to find Osama bin Laden on Pakistani soil. Their fury tracks the standard American media narrative: by punishing Dr. Afridi for the ?crime? of helping the U.S. find bin Laden, Pakistan has revealed that it sympathizes with Al Qaeda and is hostile to the U.S. (NPR headline: ?33 Years In Prison For Pakistani Doctor Who Aided Hunt For Bin Laden?;?NYT?headline: ?Prison Term for Helping C.I.A. Find Bin Laden?). Except that?s a woefully incomplete narrative: incomplete to the point of being quite misleading.

Dhanmondi Brickbreakers on Vimeo

Dhanmondi Brickbreakers on Vimeo

The traditional form of brick breaking has now been replaced by machines that do the bulk of the job. As with most low paid jobs in Bangladesh, there are many associated risks.

I am going to Die on Monday at 6 15 pm

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

When Marc Weide’s mother who was 65 was diagnosed with terminal cancer, she chose euthanasia. Here, we publish his shockingly frank diary of her final days

Monday February 11 2008

5.30pm: Dad is bent over the toilet bowl with a brush in his hand and a scowl on his face. I walk up to him. “Shall I give you a hand?” Dad begins to snicker, abandoning any attempt to make sense of the situation. We stand shoulder to shoulder with our backs to Mom, who paces around the patio with a newly fitted catheter in her hand.

The catheter has been put in by her nurse, Marianne to enable her doctor, who will be with us in half an hour, to give Mom a lethal injection. But instead of having a moment of peace with us, as Marianne suggested, Mom demands that we clean the toilets. Both upstairs and downstairs.

My brother, Maarten, is sitting on the edge of the bathtub, staring out of the bathroom window.

“Imagine,” he mutters. “Her last hour, spent like this.”

This is the Netherlands, where voluntary euthanasia is permitted, as well as physician-assisted suicide. This is the day my mother has chosen to die, and the toilets need to be spotless.

Three months earlier

I’m on a writer’s retreat in the UK, where I have been living for the past three years. I’m working on my novel when my mobile phone rings. The display shows it’s Maarten, calling from the Netherlands. Mom’s test results have come back.

“It’s secondary cancer in her lungs.” He pauses. “They think she’s got two to six months left.”

Continue reading “I am going to Die on Monday at 6 15 pm”

Jane Nona

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

I had the wonderful privilege of spending one week next to Jane Nona?s bed at the Peradeniya Teaching hospital in Kandy. 75 year old Jane Nona?s statistics could well have been 15, 15, 15. The smallest 75 year old woman I must have ever seen. She had married when she was just 15. Very proudly she tells me about how she gave birth to six strapping baby boys and one girl, all in her own home. A midwife had come and cleaned her up and held burning coals on which medicinal herbs were thrown in, her only means of sanitization. ??He was tall, fair and very kind to me? she says about her husband who had died 15 years ago. ?I knew nothing when I married him, I was only a child. He knew so much more? That had been sufficient for her. She didn?t have any complaints about him, her life, her children, her economic status or her even her reason for coming to a hospital for the very first time in her life. Her grandchildren had forced her to have a check-up. She suspected something was wrong but had no idea what it was. ?I am ready to die but my grandchildren want me to stretch it some more? she says. I looked at her file. She had a prolapsed womb. A small repair was scheduled. She had never before needed to see a doctor and never stayed in a hospital even once in her 75 years. What a blessed life, I thought. I was a veritable live-in compared to her.

She was daunted by the procedures, the examinations, the numerous scans, blood tests, especially because the doctors were mostly male. ?I have no idea what they are telling me child, what on earth is a isscan? Can you come with me when he does it?? I check with doctor and he smilingly says ok. She was schoked he could see right inside her womb. ?If my husband was around and he knew I was doing all this he will jump in the well and die? she embarrassingly declared. We went through most of the tests together. This supposedly more educated and informed 41year old from the city, was learning so much more about life from Jane Nona than any other lessons she must have learned.

Continue reading “Jane Nona”

Ekti Mujiborer Theke

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

He was the quiet one amongst us. The shadow that accentuated the highlight. In an organization known for its creativity and exuberance, Mujibor was the unsung worker. He swept the floor, lugged things around and was the one everyone called upon when things got bad. Looking for a picture of him, I realized he wasn?t even listed in the Drik Family Profile section. He never got mentioned in the acknowledgements, except for a general thank you to ?all the others who helped?. I could find no photograph of Mujibor, except for the one I took when he died.

His is the typical story of the rural poor. With little education and no special skills, making a living had become difficult. His brother Moti, and cousin Delower who work at Pathshala and Drik, introduced him to us. A low paid job in the city was better than being out of work in the village. Drik also provided opportunities to learn. Mujibor needed to send money home, so sharing a mess with colleagues was the cheapest way to live. Skimping on food, another way to save more for the children?s education. Not a wise decision when one is in poor health, but Mujibor had little choice. The extra food allowance we provided was also sent home rather than spent on meals.

When he was diagnosed with TB, my sister Najma arranged for his treatment. But the treatment for poverty is more complex and needs long-term solutions. Over a third of TB cases in Bangladesh go undetected. Many of us who might be infected by TB face none of the consequences. A decent regular meal is often enough to keep the disease at bay. For many however, a decent regular meal is a tall order. With spiraling costs of food, and high house rents, sending money home, is often at the cost of one?s longevity. A trade off that many accept as given. Mujibor was 40ish. Not many people in Bangladesh know their exact age. Few have birth certificates. His life was unexceptional, his pay was unexceptional, his death was unexceptional. Once one accepts the reality of poverty. It is that acceptance, that the have-nots have to accept such lives and such deaths, that is exceptional.

Mujibor?s salary was considerably more than the minimum wage stipulated by the government. Yet he struggled to support his three children and wife, all of whom lived in the village, where costs were lower. He lived alone in the city.

I remember a migrant worker in Paris telling me. ?I live and work here, and send money home. Perhaps my sister will get married, perhaps we might even buy a plot of land, but the best years of my life are spent in loneliness and misery. Who will give me back my youth??

The inequalities between and within nations are propped up by systems which worship profit above all else. The buyers squeeze the sellers squeeze the suppliers choke the workers. A much more famous Mujibor*** had spoken of a golden Bengal (Bangladesh). That Mujibor?s followers will need to do more than name monuments after him and pursue insane acts of vengeance, for the gold to reach this Mujibor?s children.

Muhammad Al Bouazizi, a 26 year old fruit seller, set himself alight in Tunisia in protest. Mujibor?s protest was more muted. He suddenly fell ill and was bleeding from his mouth and rectum. He was immediately taken to hospital. We all rushed to his side. The doctor recognised me. He said he would take special care. He suspected lung cancer and that little time was left. We were devastated. He was transferred to Intensive Care. The family was called in from the village.

As I stroked his forehead as he lay with tubes stuck to him, I saw the taut muscular body, the kind all workers have. Like Sultan?s** paintings. He wanted water, but the nurses said it was dangerous. I was only able to convince them to wet his lips. He was parched and wanted more. We said goodbye. I used words, he spoke with his eyes.

It had been just over 36 hours when, a bit after midnight, the doctor talked of putting him on life support. We hadn?t told Mujibor, but the man knew he was dying. His gentle smile had long gone. When his brother arrived at around 1:30 in the morning, he simply said ?I?m leaving. Look after the children.? At 03:10 he had.

Mujibor and Bouzazi both died of a disease called poverty. Will the rage in Middle East and African nations spread to the rest of the world? They will say we are different, we have regular elections and a democratic system. Mujibor?s wife and children and millions of inhabitants of Golden Bengal might disagree.

*?ekti mujoborer theke lokkho mujiborer kontho? famous song sung during the liberation war, ?from the voice of one Mujib will rise a thousand other Mujib?s voices?

** S M Sultan, Bangladeshi painter known for the muscular men and women he depicted in his paintings of rural Bangladsh.

***Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (popularly known as Bongobondhu, friend of Bengal), who is acknowledged as the founder of the nation.

Our first date was the last day of his life

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

Our first date was the last day of his life

When we met online, it was as if we’d known each other forever. Then came the tragedy I’ll never forget

BY LORRAINE BERRY

A photo of Yves.

I woke up when Yves thrust himself off the mattress. “My head is killing me,” he said. “I’m going to take some more Tylenol.”

I heard him open the cabinet door, turn on the water as if pouring himself a drink. Then a loud bang startled me from bed.

Yves slumped on the floor, his back against the wall, his side against the bathtub. Tylenol was scattered on the tiles.

“Help me stand up,” he said. But when I wrapped my arm around his waist and pulled him toward me, we both fell forward, my back hitting the vanity as I struggled to cushion him from the fall. His eyes fluttered. He was clearly in pain.

“I think we should call a doctor,” I said.

“No, no,” he said. “I just need to get back to bed. Give me a minute.” Then he closed his eyes.

“Yves,” I said. No response.

I sat beside him, stroking his back, letting him know that he was not alone, while we waited for the ambulance. I had only met Yves in person that day. But it felt like we had known each other for a lifetime.

I’m not sure what made me get in touch with Yves when I saw him on Salon personals. How can we untangle the mysterious calculus that is attraction? I liked how he playfully listed the languages he spoke as “French, English, and Body Language.” I liked the description of the woman he was seeking: “sensualist a must. a self-confident goddess too. a mermaid is also welcomed.”

I’m sure other women looked at his profile and thought “nope.” But I read it and saw a kindred spirit. He lived in Montreal, and I could tell from the way he wrote that he was Quebecois. I liked the idea of the two of us communicating in two languages. “This online dating thing is well ? difficult,” he e-mailed me early on. “And I’m a bit ‘clutsty’ at it.”

It was the “clutsty” that clenched my heart.

Continue reading “Our first date was the last day of his life”

The ambulance is more Muslim than you

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

The ambulance is more Muslim than you

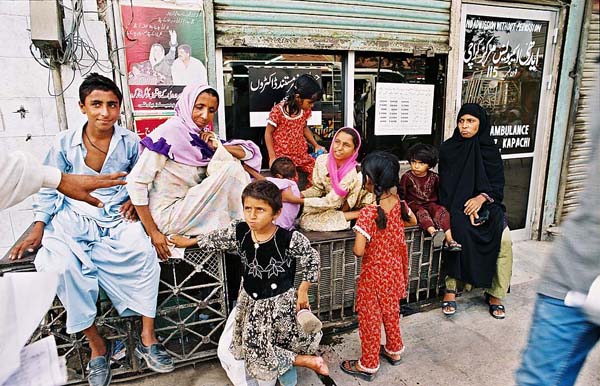

- Abdul Sattar Edhi and his wife Bilquis having breakfast in their home in Karachi. Their bedroom that doubles as their dining room. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World

‘The ambulance is more Muslim than you’.?That was the answer Abdul Sattar Edhi gave to a question when once asked ‘why must you pick up Christians and Hindus in your ambulance?’ By any stretch of imagination, Abdul Sattar Edhi is an enigma to most people. None of us truly understand him. I often think that Edhi walks a fine line between passion and lunacy. I am not able to comprehend why this man insists on doing what he does, in the capacity that he does it, for as long as he has done it for. The heart wants to register it, but the mind questions the motive.

Witness

Subscribe to ShahidulNews

![]()

6th July 2005

?This man lying here, brought me to this world. He educated me, clothed and fed?me, stood by my own bed in hospitals, stood in the gap for me at school, prayed?for me unceasingly, blessed me, guided me and counseled me and gave me?strength to take the next step. Yet, I watch him lying here, and there is nothing I?can do to stop him from dying??These were my thoughts on a chilly morning in the last room on the left wing of?Lakeside Medical Centre in Kandy five years ago. I felt helpless and useless.

Here I was seated and watching his life ebb away and I could do nothing.?What use was I? Or anything else in this world, if it can?t save the life of a man?such as him ? my father. ?God, are you really there?? I asked a blank wall.?It was also Terryll?s birthday, so I had plans to go back to Colombo that day and?return the next day, to uselessly stand by him. Yet I wanted to be there, in my?desperation to share whatever he was going through. To let him know I was?there, because I believed that even in his comatose state, he heard our voices.

For only a week before, I had spent the whole day with him near his bedside and?sang all the old Tamil songs we used to sing as children. And I saw a smile and?a tear run down his cheek. So he heard me. And that tiny factor was comforting.?What was I trying to do? Ease my conscience? For all the time I did not spend?with him? For the trouble I put him through as a teenager? For the anxiety I gave?him as an adult? I didn?t know. Perhaps he knew. We bonded that day like never?before. Even in his state, we connected. Like we always did. My father and I.

I stood up to leave, my eyes never leaving the respirator and his one hand on?his belly moving up and down which was the only sign of life. And suddenly the?movement stopped. Just like that. I knew the end was here. I handed my baby?(Zoe was then nearly 2 years) to the nurse and although we were asked to leave?the room, I wanted to stay by his side. To make sure they did everything right.

Suddenly everything was clear to me. This was the end. It was time to let go.?This man lying here will no longer be my strength. I had to be his. I cradled his?head in my hands, I whispered ?Dada I love you. We all love you. Go in peace.??The medics turned him face up. He grimaced with his eyes closed. I put his?hands together, straightened his legs and once again held his head up so the?blood would flow out and not block his throat. I didn?t cry. I wanted him released.

His pulse had already stopped. The doctor asked if they could use the electric?shocks on him as a routine procedure. I told them to leave him alone. His face?relaxed, he looked so peaceful. I put my head down on his chest. There was?nothing. My everything was suddenly nothing. I still didn?t cry. I helped the nurses?take out the tubes and clean him up.

He looked so peaceful, in a long time. Yet through the 7 months since diagnosis,?he never once complained. Not even when they stuck needles in his stomach?to release the fluids. He would smile and thank the nurses and compliment on a?good job done. I turned around and held the doctor?s hands and thanked for the?efforts, I held the nurses hands one by one and thanked them too. That is what?he would have done. Blessed them and thanked them profusely. The pathologist?covered his face with his arm and sobbed against the wall. Dada had coaxed him?several years ago to pursue his studies and make a man of himself. There were?nurses in the room he had recommended for jobs.

I filled out the death certificate calmly. Everything was so clear and programmed.?Name of deceased: Walter Jonathan Sinniah. Time of death: 1.45pm. Cause of?death: General System Failure due to multifocal carcinoma of the liver. Parent?s?name: Peter Murugesu Sinniah and Mary Sinniah. Place of Birth: Deniyaya.?Place of burial: General Cemetery, Mahiyawa. Witness of death: Jeevani?Fernando. Relationship to deceased: Daughter. I couldn?t write anymore.?I wanted to remain a witness to his life rather than his death. I had witnessed 35?years of it that day. And even now, it is his extraordinary life that challenges me?on a daily basis. Not his death.

Jeevani Fernando

Bargaining With A Six Year Old

By Jeevani Fernando

?I want a rickshaw from Bangladesh Mummy, and don?t forget the rickshaw puller too?. This was her trading skills for my missing her cake cutting ceremony on her 6thbirthday yesterday.??She had been all dressed up, poised with cake, candles, knife and family, waiting for me to come on skype and watch her through webcam.??And I was held up at a staff meeting where ?changes? were being debated.??I am so glad that my 6 year old daughter has adapted to changes in her life so quickly and so joyfully and with a zest for life and its challenges that I wish we grown ups had.??She ended the bargain by simply stating ?It?s okay mummy, don?t feel bad. I know how important Drik is to you?.??I must have done something right to deserve children like this.??Because, I almost didn?t.

Six years ago, she nearly died. I nearly died.??Somewhere between stopping the pill and getting a permanent implant, my gyno died. And unknown (ahem) to me, a new life was growing within.??I neglected. I ignored. I didn?t want.??I already had two. I already had a very methodical, routine, life. Two kids in school, me enjoying my part time job, two puppies, one husband.??Life was good.??And then it got complicated.??I jumped into a river from 4 feet high hoping it would go away.??It clung on to me. For dear life.??At five months the new gyno said ?you are bloody complicated, your placenta has moved away from baby, go home stay in bed, put your feet up, get up only to go toilet? ?Ya right? I thought. ?Where were you all my life?? I thought.

I underestimated the complication. The kids I already had thought I was getting uglier by the day. ?You look chubby Mummy. Daddy hates chubby? My husband sat far away from me ? although too late in the day.??The puppies grew up and started eating everything in the house. My complication was eating away my sanity.??By five months I HAD to tell people I was pregnant. Again.??My mother didn?t call me for three days after the announcement. I visualized my father?s jaw twitching in anxiety. ?How are they going to manage?? he would have thought inwardly.??When my sisters called, they asked about everything else except my pregnancy. My brother bought an extra pack of beer cans. For himself.

I wanted to crawl away and hide. I couldn?t. At seven months I bled like kurbani time in Bangladesh. No pain, no warning.??I thought it was over. She stopped moving. For the second time in my life, I feared death. I was rushed to emergency at 3am.??Blood soaked and completely freaked out. Gyno gave me that ?I told you so? look.??He tried a transvaginal scan and the scanner wouldn?t go through.???Serious? he said. Diagnosis??? placenta previa (placenta had dislodged from the wall of the uterus and was now in my birth canal, one push and it will come out with baby still inside).??He turned around and told his team ?prepare her, we need to take the baby out? I held his hands and begged and pleaded to let me stay just one day. The baby was just bordering 7 months. Still too small to be out.??She was below average in growth.??She had not received enough blood. I had siphoned it all out.??I begged and begged.??I had to sign a form saying it was against doctor?s orders and on my own consent that I opted to keep the baby.

That was one long wait for dawn to break.??I wasn?t allowed to move even to change my bloody clothes. The heart monitor picked up her soft rhythm. When all had left and I was alone, I placed my hands on my distorted belly and asked forgiveness from my baby. I pledged to take care of her no matter what.??I prayed for God to equip me to take care of a damaged baby.??That was what the doctor warned me about.??Stunted growth, possible brain damage, handicapped. I prayed that the family will accept this baby unconditionally.??I prayed that God would give me life so that I should be the one to take care of this baby.???I believe that was when the healing took place.??I had fallen asleep.??She started moving again. Her heartbeat picked up and got stronger.

Gyno decided to watch. Yet, would not release me to go home.??I was assigned a medical intern to study my case. I stayed one week.??And in that one week, I made friends with other mothers with the weirdest problems ever.??One was sweeping the garden and the baby fell out of the womb!! She had not even known she had dilated. They brought her in with umbilical cord still attached and a fainted mother. I wheeled myself to her bed and talked to her nights on end.??The baby was in neo-natal and she had no idea of the condition.??I read the reports to her. It weighed only a kilo. No wonder she did not feel it coming out. I got friends to take pictures of the thing in the baby ward and bring it over. It looked like a slightly large beghuni. My case forgotten. Temporarily.

My case is now dancing to the ?Macarena? at 6 years of age.??Complete, wholesome and an energy that keeps the rest of us dancing too.??Her simple reason to things she does is ?That?s why?