Subscribe to ShahidulNews

New Internationalist Magazine Issue 332. March 2001

If the billions of dollars in aid to Bangladesh over the last?three decades had been given directly to the poor, it would?have made a major difference to their lives. As it is, the poor?continue to struggle while the rich flaunt their ever-increasing?wealth. Shahidul Alam visits the homes of people?at opposite ends of this great divide.

The guard at the gate hesitates before questioning me. My white friend walks on. Her right to entry is beyond doubt. A cough by someone nearer the door, and higher up in the chain of command, signals my credentials and the hesitant guard makes a smart salute. I?ve been here before. At the gate of the British High Commission or the office of the UN Development Programme, for example. These are places where the?bideshis(foreigners) and the well-to-do Bangladeshis have ready access. My sloppy clothes and the fact that I did not alight from a fancy Mitsubishi Pajero were enough to give my position away. Besides, I walked differently, made eye contact with those outside the chosen circle, and was clearly not supremely confident of my position.

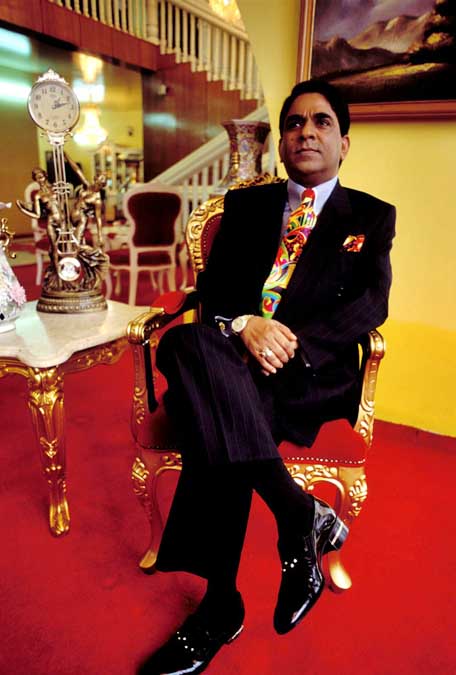

Hasib?s palatial home is in Baridhara, a part of town with the most intriguing architecture. Here Tudor houses rub shoulders with Spanish villas, with the occasional Greek columns thrown in. What are missing are the lavish gardens one might expect. Land is expensive here and homes are often built up to the edge of an individual plot and sometimes even beyond it. Only the very special ones have a patch of green, perhaps a swimming pool.

This is a land of tranquillity. No?hartals (general strikes) affect the normal flow of life. The American International School where Hasib?s children study is perhaps more expensive than the average private school in Britain, but does give his heirs the sort of training needed to blend seamlessly into the high-powered positions they will surely come to occupy. The school holidays prioritize Hallowe?en over Eid. No adulteration of ?higher cultures? by local practices is tolerated here. The one discomfort that the inhabitants face are the slums by the edge of the lake, the hungry stares from across the metal fence, the huts between the palaces, that have not yet been cleared out. The dark glass of the Pajero does reduce contact, but even the air-conditioning doesn?t quite clear the smell.

The interior d?cor of Hasib?s home matches the fantasyland exterior. This is a home appropriate to a wealthy media person whose companies receive funding from UN agencies, who is an agent for a prominent US company in the energy sector, and who is well-connected to all the major political parties. Hasib is not a person you would want as an enemy. The presence at this party of the ?lite of the city, the aid givers and takers, and a sprinkling of ?intellectuals? testifies to his acceptance in the circles that matter. Smiling photographs with former leaders Mujib and Ershad, with the US Ambassador and prominent heads of state, adorn his office, though they are appropriately changed to suit the political clime. Ershad at his most powerful visited Hasib?s office, though he was later to comment jokingly in Parliament on Hasib?s smuggling links.

These are well-travelled people, and all that is best in the world outside is present here. Cut-glass chandeliers in abundance. Leather-bound classics neatly arranged in teak shelves. Expensive paintings, mostly by artists who have died, but also by Shahabuddin, the current?enfant terrible, hang in gilded frames.

The well-dressed waiter snakes through the crowd distributing wine, beer and whisky, technically illegal in Muslim Bangladesh. This is a place for men of the world and emancipated women.

Nadia, Hasib?s wife, tosses her hair back in her revealing dress as she laughs with the US Ambassador. She gently acknowledges the minister as he walks by, excusing herself to talk to the editor of the most popular daily. She looks out for the World Bank chief, and relaxes as she spots him out by the swimming pool, talking to the head of the largest NGO. She only wishes she didn?t have to invite the MP who was found making bombs in his house. Such people give others a bad name.

The MP was a minor embarrassment to the ruling political party, especially as it had just embarked on a clean-up campaign. Fourteen-year-old Rimon was at the other end of the spectrum. He was one of several young men arrested when they were trying to make the clean-up campaign look good. They had to plant a knife in his hand in order to make the arrest. He had no previous record and the witnesses all denied in court that they had seen Rimon with weapons, but these were not insuperable problems. The fact that he was a minor was, on the other hand, a technicality that might have proved awkward. Fortunately he was too poor to make an issue out of being under- age or about being kept in jail for two years without a trial.

One could look at it as a democratic process. The system doesn?t really care about class, race or gender. If one has money, one stays out of jail. Without money, one stays in. Rimon?s mother Fatema works seven days a week as a domestic help in the home of a top civil servant. Low-paid and with no benefits, she has had to borrow over 20 times her monthly salary to try to get a fair trial for her son. The process of trying to bribe judges, paying high fees to lawyers and regularly paying the police is something she seems to have accepted. Her biggest sorrow is that the food she buys for her son doesn?t always get through to him, despite the bribes she pays to the wardens. ?I used to serve food in four plates for my children. Now I serve only three. The pain burns within me every day.?

The justice you are likely to get is directly linked to the money you are able to muster. Hasib was suspected of smuggling gold, but no-one made too much of his going scot-free on that count. Now Hasib is into bigger things. An agent for a leading US gas company, his other hat as a major media baron comes in handy. Press releases by the US gas companies appear dressed up as news reports.

He has even ?written? a book. The senior professor and the archeologist who ghost-wrote it do not seem too perturbed by the mismatch between the book?s content and the official author?s credibility as a writer. At the press launch, leading?litt?rateurs talked of the talent of the man, his contribution to society.

Rimon never even went to school. Long before his body had fully matured, he was pulling a rickshaw, helping to support the schooling of his two sisters and younger brother. Ironically, on a per-square-metre basis, his mother Fatema pays more rent for her shack than the standard rental in wealthy Baridhara. In many slums, access to water is a privilege you pay for separately. Sanitation, electricity and other amenities are all extras.

Being important vote banks, slums are controlled by local strongmen with affiliations to the major political parties. Fires rage through them on a regular basis: sceptics claim that this is a convenient way to evict unwanted residents. Sometimes fires precede a sell-out to developers.

At least Fatema has a roof of her own. More vulnerable are the domestic servants who live in their employers? homes. Many of them are children or young women. Murder, rape and inhuman torture are commonly reported. A far greater number go unreported.

The slums are the entry points for the millions who converge upon the metropolis from the villages in search of work. In the countryside the divide between rich and poor is similarly reinforced by foreign money.

Wasim Ali, a wealthy shrimp farmer in Khulna, goes around in a gunboat warding off and occasionally killing trespassers. His guard points out the shrimps, saying ?dollars swim in the water?. The World Bank assists Wasim and others in setting up shrimp-processing units and Japan buys much of the shrimp.

Lokhi Pal?s family, who used to grow paddy, were forced into selling their land to Wasim once the entire area became salinated due to the new embankments that had been built. ?We had cows and a vegetable patch,? she told me. ?All we needed to buy was oil and clothes.? Now they go during?hat (the weekly market day) to a neighbouring village to stock up on food and basic supplies once a week. The family eats well for the first three days then hangs on till the next hat day. Still attached to their cow, they send it off to a nearby village to graze but have to pay for the privilege.

Back in the city Fatema worries about her son?s health, about the money she will somehow have to repay. She worries most that unless she finds some way to get her son out of prison he will soon end up embittered. Then when he does come out he could be forced to do the kind of thing for which he could be arrested again. Right now, however, she longs to have an extra mouth to feed. For Hasib and Wasim, of course, the dollars continue to swim freely.

——————————————————-

The feature is based on facts, but the names have been altered.

New Internationalist Magazine Issue 332, March 2001.

The issue was co-edited by Shahidul Alam and the NI editorial team.

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them.

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them. When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’

When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’

Inside the aircraft it is different. They look around at the metallic finish of the interior, try on the headphones and drink lemonade. They have seats together and whisper to each other about each new thing they see. Abdul Malek, sitting opposite me, is in his early twenties. He is from a small village not far from Goalondo. This is his second attempt. He was conned the first time round. This time his family has sold their remaining land as well as the small shop that they part-own. This time, he says, he is going to make it.

Inside the aircraft it is different. They look around at the metallic finish of the interior, try on the headphones and drink lemonade. They have seats together and whisper to each other about each new thing they see. Abdul Malek, sitting opposite me, is in his early twenties. He is from a small village not far from Goalondo. This is his second attempt. He was conned the first time round. This time his family has sold their remaining land as well as the small shop that they part-own. This time, he says, he is going to make it.