Subscribe to ShahidulNews

| Preface to Drik Calendar 2006 | |

|

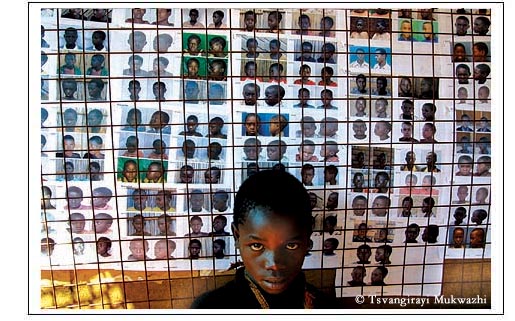

It was a stinker of a letter. Written to an organisation I knew little about. I was angered that World Press Photo (WPP) had little to do with the world and was largely about European and North American photography. Though it featured work from all over the globe, the jury, the photographers who entered the contest and the winners were largely white western males. So in my letter I had suggested that they rename themselves Western Press Photography. The phone call was a surprise. We didn’t get too many overseas calls in those days. The managing director of WPP Marloes Krijnen, politely pointed out that they too had written me a letter, still on its way, which was dated prior to my letter, and hence had not been written in response to my tirade. They had just asked me to be a member of the international jury. My letter had also mentioned that I considered WPP to be a very important contest despite its shortcomings, and should the opportunity arise, I would be interested in hosting the show in Bangladesh . This led to the second part of the conversation. While the exhibition is generally booked way in advance, there had been a cancellation, and should we want it, the show could be made available in three weeks. Having recovered from the initial excitement of being asked to be on the jury of what is considered the pinnacle of press photography, I tried to compose myself and considered the options. I needed time, and asked Marloes whether she could call back in a couple of hours. The exhibition could only be shown in its entirety, and we had faced considerable problems with our own exhibitions. The major galleries were either state-owned or belonged to foreign cultural centres not prepared to question the government, or be controversial in any way. Our work had always been critical of the government and the elite, the donor community, the patriarchal system and of the self appointed protectors of religious and family values. We didn’t know of a single gallery that would guarantee that no censorship would take place, except for our own gallery. There was just one small problem. Our gallery hadn’t yet been built. We had drawn up the architectural plans for it though, and part of the superstructure was in place, but still no gallery. I was stalling. Rafique Azam was then not the superstar that he is now. This was his first project, and we had wanted to give these young architects a free hand to interpret our ideas. I rang him up and asked him if he could build us a gallery in seventeen days! Rafique didn’t react as badly as one might have expected. He knew I was crazy enough to have meant it and having told me how ridiculous the idea was, settled down and gave me a list of all the things he would need to make it happen. He needed to work round the clock, a fair bit of money, some of it the following morning, and full freedom. There could be no slip ups in the supply chain. It was going to be a race to the finish as it was. Osman Chowdhury was a client, but it was as a friend that I rang him up. There was no way he could organise the sort of money we needed at such short notice from his company, but he was able to promise a sum that we could get started with. And he could provide it the next morning. Marloes rang as she had promised, and I said we would be happy to host the exhibition, in our own gallery. There the polite conversation ended. But that was also the beginning of a wonderful relationship between our two organisations, World Press Photo and Drik. A relationship that has blossomed over the years. It didn’t take long for the news to spread. Mr. Gajentaan, the Dutch ambassador was a friend who had a strong interest in the arts, and had arranged photo exhibitions in his home in the past. Excitedly he rang me and wanted to come straight over. WPP coming to Bangladesh was big news, and he wanted to be part of the action. He was calm enough when we told him about our plans to have it in three weeks and in our own gallery. It was when we told him he was standing inside the gallery that he flipped. There was no gallery. ?Do you realise this is the most prestigious photo exhibition in the world?? he asked. Yes, we knew. And we would have a good show. A much shaken ambassador went back to Gulshan. To be fair, he didn’t call World Press to tell them that the gallery was only being built. There was more to the story. It was 1993 and the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party were fighting each other in the streets, locked in a bitter battle for power. This we felt, could be a chance to unite these warring factions. We knew there was no chance of getting the two leaders of the parties at the same table, but the deputy leader of the BNP was Dr. Badruddoza Chowdhury, a student of my father, and we could probably approach Abdus Samad Azad through a personal friend Kaiser Chowdhury who was then the chief whip of the Awami League. Having been so critical of World Press Photo in my letter to them a week earlier, I was now extolling its virtues to two of the most powerful politicians in the country. Kaiser and my mum did the original groundwork, and I put in a good pitch about how this would demonstrate to the nation that they were forward looking political parties, and how much media coverage the event would have. It worked, and they agreed to jointly open the show. Now I had another tool to play with. While local media didn’t really know much about World Press, the fact that these two sworn enemies were going to open a show together was big news, and we managed to get the media excited. Mahfuz Anam of The Daily Star, the biggest English daily, agreed to do a whole media campaign around the event, and the bits were beginning to fall into place. At the packed press conference on the veranda of my parents’ home (Drik rents the upper floors), we were stalling for time, to let the paint dry in the gallery upstairs! ?rp?d Gerecsey the curator (who later went on to become managing director of WPP) and Bart Nieuwenhuijs, the board member who had come to setup the show, huddled with my colleagues and spoke in agitated whispers. Who was going to bell the cat? Eventually it was Bart who came up to me. They wanted to put in nails on the freshly painted walls! We did put in those nails, and the show was a spectacular success. The two deputy leaders cut the ribbon together, and confessed that they enjoyed sharing a cup of coffee, despite their political differences. The media went gaga. WPP and Drik had together pulled it off. Since then, the two organisations have continued to work together at many levels. An impromptu seminar for press photographers followed. We arranged for the show to go to Kathmandu and Kolkata. Rabeya Sarkar Rima of the Out of Focus group became the first Asian child jury member. I remember telling Marc Proust when he came to curate yet another WPP exhibition in our gallery, that Nurul Islam, the young man who sold us flowers in Monipuri Para, had also been a former child jury member. We had the WPP retrospective exhibition at the National Museum at the first Chobi Mela, the festival of photography that we launched. We collaborated on many other things. We started nominating young Asian photographers for the Masterclass, and one year, two photographers from Pathshala, our school of photography, GMB Akash from Bangladesh and Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi from Zimbabwe were amongst the twelve talented photographers in this international pool. Pathshala itself relied heavily on WPP for its existence. With no state or other external funding, it was always going to be difficult to setup and maintain a school of photography in our region. We utilised the first WPP seminar programme to launch the school, and the tutors and the workshops that WPP provided became important anchors for what has now become a degree programme. WPP even provided a grant which was a big help in those early days. Since then we have collaborated on training Asian and African photographers in regional programmes organised in Jakarta and Kenya , and been involved in longer term educational projects in Sri Lanka and Tanzania . I myself worked in the jury another three times, once as chair, and I have spoken at several WPP events. Interestingly, it was the very issues I had raised in that original letter which the two organisations have worked together to try and solve, and both WPP and Drik are very different organisations today. It is to celebrate that friendship, on the 50th Anniversary of World Press Photo, that we put together this calendar. The images are by the majority world participants of WPP seminars and their tutors, some of the finest photographers around. It is a protest against the continued use of exclusively white western male photographers to document the majority world that developmental agencies and western media have made their standard practice. It is a direct answer to the superior race argument that they continue to use to justify their actions and to dismiss our work when they say ?they don’t have the eye?. Shahidul Alam |

|