It was in the early 90?s that Pedro had written. I had only heard of this famous Mexican photographer, a pioneer of digital photography and author of the first photo essay on CD ROM, ?I Photograph to Remember?. It was a gentle, intimate and deeply perceptive essay on the last days of his parents who were dying of cancer. I remember the image of his father looking as if he could fly. He was bringing out his new CD, ?Truths and Fiction? and wanted me to write an introductory text, something about my responses to the new digital technology. We didn?t have email then, and faxes were expensive, but we continued a dialogue that went far beyond his CD, or his subsequent books.

We met several years later when Ma, Rahnuma and I had gone to Arle, in the South of France. I had a small exhibition in the festival there. Rahnuma was doing her PhD in Brighton and Ma and I were going to join her there. We would go on to France, and Italy and then go overland through the Alps to Holland. It was before Schengen, so we needed visas for each country that we needed to cross. Armed with invitation letters from friends in each country, Ma and I did the embassy rounds. Friends at the embassies helped, and we even got recommendation letters for Rahnuma which she could use in London for her visas. Undaunted by the sign inside the Belgian Embassy in Dhaka, that said ?We do not issue tourist visas?, and other equally friendly mementos in the remaining ones, we gathered all the visas, joined up with Rahnuma in London and headed off to Paris. The organisers were paying for my trip, but Andre Raynouard at the Alliance, had kindly arranged for trips to France for photographers Shehzad and Mahmud as well and we all met up in Paris. Trips to Editing, the agency that represented us in France at that time, and visits to Magnum were warm ups to Arles. We took the train to Marseille where Gilles and Isabelle picked us up. Driving through the sunflower fields that Van Gogh and Gaughin must have painted, I remember wondering if the mottled bark of the trees in Arles had inspired their rugged brush strokes.

Pedro had a massive exhibition at Arles, and I remember marvelling at the digitally produced images printed on canvas, hanging in gilded frames, all along the walls of what appeared to be a medieval church. Pedro was showing the new CD on a Mac to his enraptured audience. I too had a go playing with this new toy. Thinking I was Hispanic, Pedro came up to me and asked if I would like to see the Spanish version. In an air of nonchalance I shrugged, but suggested I might be interested in the Bangla version. Pedro smiled and told me of this very good Bangladeshi friend that he had, called Shahidul Alam, who he would introduce me to! The bear hug that I got when I revealed my identity nearly did me in.

The rest of the trip went well too, but the highlights were, being in Milano at the house of Gabriela Calvenzi, the picture editor of MODA, when Italy beat Bulgaria in the semis of the world cup and that breathtaking train ride through the Alps. We visited Nipa and Alam in Basle, and they drove us through the sunflower fields and gentle waterfalls in Switzerland. Ma was disappointed that they did not check our German visas on the train. We had gone to so much trouble to get those visas! Walking through Amsterdam?s red light district with Ma was another interesting experience, but what I remember more of that city was the meal we had. I had been in the jury of World Press (WPP) the two previous years, and had many friends there. Marloes Krijnen, the managing director of WPP took us all to dinner at a fancy Argentinean restaurant. Ma ordered a very exotic sounding dish, which we were a bit jealous of, until the waiter turned up with a baked potato with a blob of butter on top!

The US trip to visit Rahnuma?s brother Khadem, was relatively uneventful, except for the immigration officer?s zeal in checking us out, as he always did with ?certain types of passports?. This resulted in us missing our flight, and I was in full ?journo mode?. Out came my notebook, my digital recorder, I took copious notes, interviewed people, quizzed him on what he meant by ?certain types of passport?. The guy was rattled enough to upgrade us to business class for appeasement. He tried to mumble something about our garb being inappropriate, but my cold stare put a stop to that.

We didn?t go to Mexico that trip, and my first opportunity came in 1996, when the Centro de la Imagen invited me to speak at PhotoSeptembre. As it is now, there was no Mexican embassy in Dhaka. even my foreign secretary friend had been unable to extract a visa application form from the nearest embassy in Delhi, let alone a visa itself. I tried plan B. The consul general in London had heard of me and wanted to help. We exchanged phone numbers as I went off to Fotokina in Cologne, loathe to hang around in London while the bureaucrats decided what to do with me. The consul phoned me in Cologne, asking me to take the night train, in order to arrive in time. Groggily, I made my way from Waterloo to the consul office. True to his word, the consul managed a visa in time for me to race to the airport and catch my flight to New York and on to Mexico City.

Being the only African or Asian in this huge meet with over 800 exhibitions should have been daunting, but my naivet? helped me overcome such inhibitions. I was thrilled by the work on display in this amazingly culturally rich city. Manual Alvarez Bravo turning up on the day of my talk should have been enough. Reaching across to the next table over dinner to chat to Gabriel Garcia Marquez should have left me sufficiently awed, but I was too excited to be fazed by any of this. My memories were more of the trip to Oaxaca that Patricia Mendoza, the director of Centro de la Imagen had organised for a few of us. It was a small but interesting group. Fred Baldwin and Wendy Waitriss who ran Fotofest in Houston, Alasdair Foster (this was when he ran the photo festival in Edinburgh and before he became the director of the Australian Centre of Photography), and Marcelo Brodsky, the president of Latin Stock from Sao Paolo, made up our motley team. We passionately argued, and fervently planned; charting out the routes that we felt photography should take. I remember those torrid moments, but my most distinct memory is of the midnight visit to the Aztec temples that Patricia had managed to organise. The temples were off limits after sunset, but Patricia knew everyone, and had arranged for us to go on a full moon. I remember walking along the ancient corridors of the shrine, glistening in the moonlight, the quiet and eerie stillness, the sound of the bats, the whoosh of the owl, and sparkling in the valley below the gently glowing city of Oaxaca. I have very different memories of Francesco Toledo, sitting on the red clay, chatting to other artists. This was the artist who had raised millions and donated his own work, to set up some of the finest museums and galleries to be found. I could imagine him in the dried up pond in Charukola, or in Modhu?r canteen, passionately debating the merit of some work of art. While the visions included Toledo and other students, sadly, I couldn?t see the directors or the DGs of our own institutions coming out of their dull carpeted offices with towel backed chairs and touching the earth with such sincerity.

I remembered the brightly coloured shawls, the hibiscus and tamarind drinks, the blue beans and the fried crickets. So when Pedro asked me to speak at the 10th anniversary of zonezero.com I could hardly refuse. There was still no embassy, and no guarantee that it would work again in London. The world had changed in between, and Pedro was loath to have a bearded Muslim, negotiate immigration officers in the ?land of the free?. So he arranged for a direct flight to Mexico City from Paris, and sent a very official looking letter with lots of stamps to the embassy there. I had been emailed a copy. I was going to Prague enroute, so two visas needed to be managed. Luckily Martin Hadlow of the Media Development Loan Fund in Prague who had invited me to Prague, knew the ambassador in Paris, who knew the ambassador in Bangkok, who spoke to the consul general in Kuala Lumpur. The Czech consulate gave me a multiple entry visa immediately but Mexico was not going to be so easy. I was going to buy the tickets to Prague, Amsterdam and Manchester in Paris. So I had a ticket to Mexico and no visa and a visa to the Czech Republic but no ticket. It was going to be fun.

We were all approaching Prague differently. Sameera and I travelled to London together, and I went on to Paris. Czhoton had been doing a long assignment in Denmark, so he flew directly from Copenhagen. Shabbir unfortunately had been denied a visa, for the ?Catch 22? reason that he had never been to Europe before. I was staying with Sylvie Rebbot, the picture editor of Geo. In the morning, it was Sylvie who navigated the answering machine sil vous plez?s, but ended up getting no coherent response from the embassy. So armed with a map, I walked down Strassbourg St Denis to rue de? . The embassy was closed. With my rusty French, I could work out that the 16th September was Mexico?s Independence Day. Luckily, and rather uncharacteristically, I had kept a margin and had resisted purchasing my other tickets until I had my Mexican visa.

Dominique from Contact Press recommended their travel agent who was very helpful, but struggled with my itinerary. A Paris Prague single came to over $ 1,200! A return would work out cheaper, but I needed to include a Saturday night. That meant missing out on my show in Groningen, as I wouldn?t have time to go on to Manchester and then to Oldham and back to Paris in time to catch my flight to Mexico City on Tuesday morning.

Eventually we managed a Paris, Amsterdam, Prague, Amsterdam Paris ticket that was reasonable, and good old Easyjet from the nearby cybercafe, provided a Paris Liverpool Paris flight, at a quite good price. All I now needed was that Mexican visa. The visa officer I met on the 17th was very pleasant. Pedro had provided an imposing looking document, with several stamps. The sort bureaucrats love. Gauging that they would issue the visa, I hesitantly asked how long it might take. ?48 hours? was the short reply. I was in trouble. All my budget price tickets were non refundable and non endorse-able. Besides, I?d already killed two of the four days I was meant to have for this meeting in Prague. Luckily, I had my itinerary with me. The sight of eleven flights, two train journeys and four car journeys, across ten cities in three continents over fifteen days, should have been enough to convince her that I was totally mad, and shouldn?t be allowed in any country, but it worked, and she agreed to let me have the visa in an hour (my flight to Amsterdam was in the afternoon). There was the minor matter of the fee. 134 Euros to be paid in cash. I gulped. In these days of electronic money, one rarely carried cash around. No problem. I had my travellers cheques. I would be back in a jiffy with the money. Could I have my passport please. ?Sorry, we need the passport to process the visa.? Logical enough, but I was stuck again. I combed all the banks in the neighbourhood, but they wouldn?t give me an advance on my credit card. Eventually a bureau de change with a trusting officer, decided he would take the risk, and cashed my travellers cheques without a passport. Back to the embassy, collect visa, rush to Sylvies?, train to Garu du Nord (Charles de Gaulle, doesn?t have a left luggage), pick up luggage, and finally with visas, tickets and passport, I dashed to the airport. Paris, Amsterdam, Prague, Amsterdam, Groningen, Amsterdam, Liverpool, Manchester, Oldham, Manchester, Liverpool, Paris and then on to Mexico City. In between Martin had taken us on a lovely night walk across old Prague. Drew, arranged the Liverpool, Manchester Oldham circuit, and Lotte and Anonna, joined me in Groningen, where Maria and Ype gave me a grand tour of the Norderlicht (the Northern Lights) Festival. Opening up galleries in the middle of the night, Bresson, George Rodgers, Capa, all in one go! And of course there were my two shows, in the synagogue in Groningen and the one in Gallery Oldham that I had gone to see.

Mexico was all that it had promised to be. Great speakers, old friends, wonderful presentations. Our own session was unusual. There were only two speakers as opposed to the customary four. Brian Storm, Bill Gate?s right hand man at Corbis, versus this bearded Muslim from a small agency in Bangladesh! Techno power versus spunk! It was the classic duel and the gallery loved it. I don?t think Gates will be making a takeover bid for Drik just yet. It was again at Pedro?s on the eve of the talk. Trish was leaving for New York the next day, for the judging of the Eugene Smith Awards, and this was a quick dinner she?d arranged. Mark (senior curator of Victoria and Albert Museum in London) and I were the only guests. Pedro took us for a walk along Coyocan. We went down the streets where Frieda Kahlo and Trotsky used to live. Visited Cortes? palace where Pedro and Trisha were married, and soaked in the energy of Pedro?s bustling para.

There were of course the more traditional touristy visits. I?ll remember Maximilian?s palace for its ornate loo, and the boat ride along the ?Floating Gardens of Xochimilco? and the Aztec dance amidst the pyramids. It took a while to get used to the fact that we had a film crew following us for most of the trip. The producer, Michel, had been a war photographer for many years, but was now known for his sensational environmental films. We talked of the possibility of him coming to Pathshala to teach. The highlights for me were the visit to Fototeca in Pachuca where we saw the original glass plate of Zapata?s official portrait. The joy of holding history in my hands, was only to be topped by the visit to the incredible ?Museum of Anthropology? in Mexico City. I had been told about this famous museum before, but hadn?t quite made it during my last visit. This time round I was determined to make it. North Americans, Europeans, Latin Americans and one lone Bangladeshi made a curious mix.

What a museum it was! Having visited some of the most famed museums around the world, I felt I had seen it all, but this one simply took one?s breath away. Apart from the sheer exquisite nature of the exhibits, I was enchanted by the love and the care that must have gone into setting up the display. Each piece of stone, was carefully positioned, thoughtfully lit, and displayed as a prized possession, which of course they were. The tombs descended down an intricate stairway, with sections cut out, so we could visualise our descent into the burial grounds. Lights carefully placed at floor level, lit up small artefacts, that characterised the personalities of dead. Tools for the rights of passage, a child?s toy, a garment to take one across the border of the living and the dead. The walls, the floor, the ceiling, the distant vision, each had a role to play in this wondrous display.

I had finally managed to free myself from my endearing film crew, on the morning of departure. I was not going to miss the Koudelka show. Hanging around the Palais Bella Artes, waiting for the doors to open, I made rapid notes of what was left on my ?to do? list. Gift for people back home! I was in trouble. But Koudelka was having none of this. This was an exhibition that could not be rushed. The sheer versatility of the man was amazing in itself. And then to see, in his latest reincarnation, images with such mastery of tones, such splendid play of forms, such freshness of vision, was simply mind blowing. Shopping time had to go. I needed excuses. Still reeling from this visual feast, I dashed to the alleyways at the back of the Sheraton. There were no ponchos for Topu, but a few revolutionary T shirts, and the odd Mexican trinket would have to do.

I stopped in Paris long enough to drop in at Reza?s and pick up the CD for the new Drik calendar. Sylvie had arranged an assignment for me with Geo, and having taken over the Contact Press Office, I asked the writer to visit me there. Michel Szulc Krysnovsky had just returned from his assignment in Dhaka where Pathshala student Sunny, had worked as his fixer. He brought his portfolio over, and we talked of exhibition possibilities. Robert gave a copy of his new book on the Cultural Revolution for Rahnuma and me, duly stamped with his new Chinese signature. A few hours sleep at Sylvie?s and it was time for the airport again. I would have three whole days in Dhaka before heading off to Taipei. Bliss.

![]()

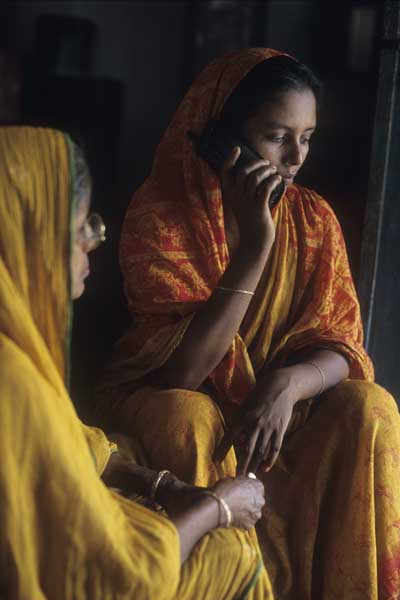

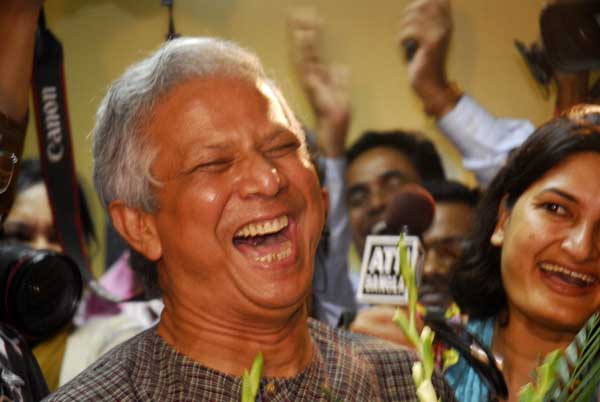

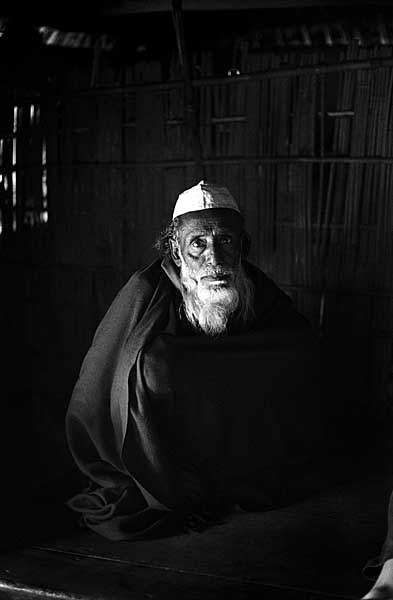

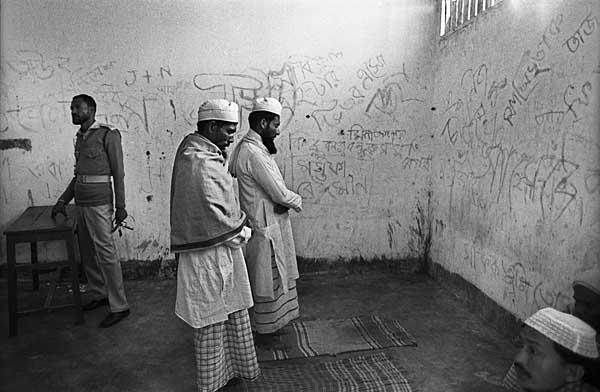

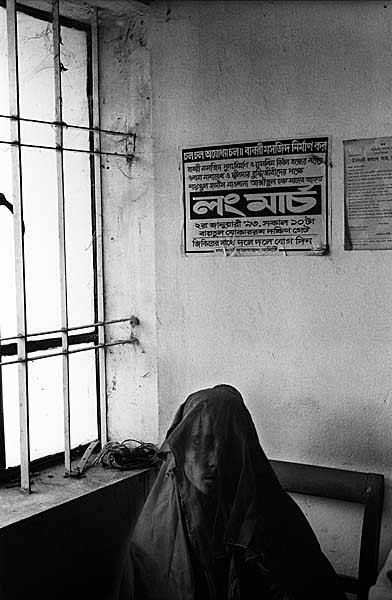

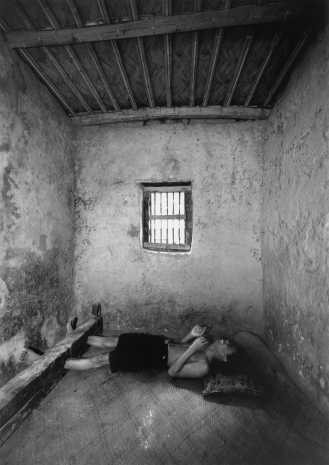

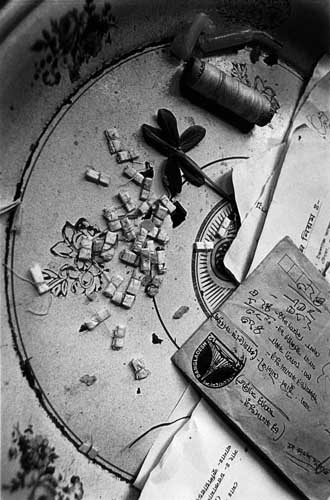

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh,

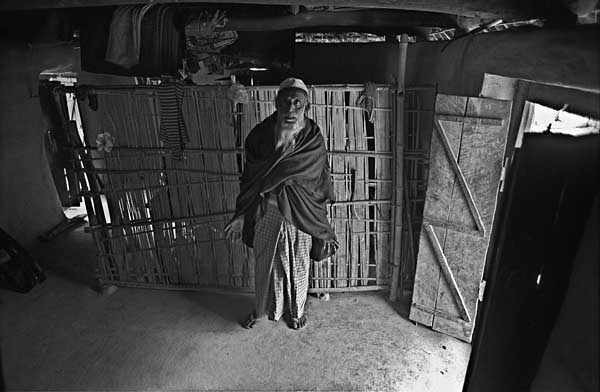

? Md. Mainuddin, Bangladesh,