![]()

![]()

Pathshala, The South Asian Institute of Photography celebrates its 10th anniversary

Elita Karim

Star Weekend Magazine Volume 7 Issue 5 February 8 2008

?D. M. Shibly

?D. M. Shibly

Members of the Pathshala family have a lot to celebrate. ?My son had once written an essay in class, where he wrote that his mother is a photographer,? says Munira Morshed Munni, freelance photographer, photo editor at Drik News and teacher at Pathshala. She is also one of the first students of Pathshala, and has been with the school for the last ten years. ?His teacher, upon reading the line, immediately cut it out, assuming it to be a mistake made by the child. Later on, I had to go speak to her and explain that I really am a photographer and also make a living out of it. She was dumbstruck for a while.? You can’t blame the teacher, adds Munni. It is still very difficult for the society to accept this art-form as anything but a hobby, a side interest or a skill that is more or less limited to documenting wedding receptions or capturing nice images. Most people are unaware of the detailed calculations made by the seasoned photographer, of the possible number of angles that can be used for one shot, or the analysis of composition, frame and subject in the blink of an eye.

Left to Right ? Saikot Majumder, Sazzad Ibne Syed, Abir Abdullah

Left to Right ? Saikot Majumder, Sazzad Ibne Syed, Abir Abdullah

Pathshala, The South Asian Institute of Photography, located on Panthapath, has played a pivotal role in the last decade, in changing the social attitude towards photography as a profession. Offering basic and advanced levels courses in this field, the institution also offers diploma and Bachelor equivalent courses to students. Very soon, a Master’s level programme will also begin in collaboration with the University of Liberal Arts. The school is also a part of the upcoming regional Master’s programme between universities in Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, Nepal, Norway and Pakistan.

Back in 1998, Pathshala had begun as a part of a three-year World Press Photo educational initiative in 1998. As the name Pathshala symbolises the ancient education system held in the open air, under the shade of a tree, free from the confining walls of a classroom, the institute emphasised on not merely conventional teaching the students. It allowed students to ask questions and develop their own style and perspective. The school was designed in a way that leads students to experience knowledge beyond the confines of the discipline.

Dr. Shahidul Alam speaking on the institute’s anniversary ? D. M. Shibly

Dr. Shahidul Alam speaking on the institute’s anniversary ? D. M. Shibly

According to Shahidul Alam, the Principal of the school and MD of Drik, Pathshala strives to do much more than teach photography. ?It is about using the language of images to bring about social change. It is about nurturing minds and encouraging critical thinking. It is about responsible citizenship. In a land where textual literacy is low, it is about reaching out where words have failed. In a society where sleek advertising images construct our sense of values, studying at Pathshala is about challenging cultures of dominance.? Dr. Shahidul Alam speaking on the institute’s anniversary. According to Alam, in the South Asian region, the need for a structured education in photography has always been felt. Since photography plays a significant role in the mainstream media, this need is mostly felt in the field of photojournalism. ?The people’s right to information is generally not recognised by the official media in many countries,? he says. ?This is clearly also true for the SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation) nations. The lack of sufficient professional skills in the media, especially in the field of photojournalism, has also allowed successive governments to pass on propaganda in place of news, and the people’s role in governance has been totally ignored.? Interestingly enough, most students, who go to this school, are studying subjects like Engineering, Medicine, BBA at other universities to comply with the conventional social mindsets. There are some, however, who end up choosing between passion and tradition, hence letting go of the so-called educational system approved by society. One such student is Azizur Rahman Peu, editor of Drik News, teacher at Pathshala and also one of the first students to have entered the school ten years ago. ?I was studying medicine in Rongpur,?he says, ?when I practically ran away from home to Dhaka. I wanted to be a journalist. Back then, I didn’t know how one would define a journalist. I used to think that a photographer was, obviously, what described a journalist, capturing and documenting moments in history. My love for photography, eventually, led me to start studying here at Pathshala.? Pathshala’s certificate awarding ceremony. Blaming not only the social net, but also the media in Bangladesh, students claim that even inside newsrooms, photographers are not given their worth. A photograph tells a story as well, which should complement the journalist’s written work, rather than act as a side support. ?Newsrooms have news editors,? says Shahidul Alam. ?However, the concept of a photo editor is not seen in newspaper offices here.? According to Alam, it was the Independent in the UK which had practically revolutionised the way photographs were used in newspapers, hence breaking the system. ?Other newspapers like the Guardian had to eventually accept this idea as well.? Pathshala also has regular academic exchanges between Oslo University College in Norway and Edith Cowan University (ECU) in Australia. It is not really an exchange programme, since students from these countries come to Bangladesh to learn about photography and not the other way around, adds Alam. However, this provides Pathshala students an opportunity to share experiences with students of very different backgrounds. ?The long-term partnerships with Sunderland University, Bolton University and the Danish School of Journalism, offer educational opportunities for students with other world class institutions. The internship opportunities at Drik, Chobi Mela and Drik News offer on-the-job training that is invaluable in professional life. The regular participation in international festivals and workshops provide a world-view essential to becoming established in the global marketplace. And then there is the acid test. Emerging students are in demand, and ever since Pathshala started, all students who have graduated are gainfully employed. Some are already at the very top of their profession,? says Alam. Celebrating a decade with fireworks. Norman Leslie, the programme director from ECU, says that his students have had the chance to experience life in all its reality and colours through this exchange programme. ?ECU is located in Perth, which is a city extremely isolated even in Australian terms,? says Norman. ?Students from this university, besides having the advantages of international exposure through this programme, have also created a certain bond between the two cultures which is extremely important when it comes to the art of photography.? Even though passionate about art and photography from an early age, Shahidul Alam had decided to take up photography as a profession by accident. Back in the 80s, Alam was doing his PhD in Chemistry in the United Kingdom. As was the norm and still is in the society, studying a proper subject define the integrity and depth of being a true man. ?And that is what my parents believed as well,? says Alam. ?I did not have much money and would work to pay my tuitions.? One of his close friends got into the airlines business and asked him to fly to the United States with him. ?A poor student like me would never get this opportunity ever again and so I decided to go. My friend in the UK asked me to bring him back a camera since cameras were cheaper in the US.? Alam got a full set complete with a tripod and lens and got back to the UK, only to find that his friend did not have the money to pay him back. ?And I was stuck with it!? laughs Alam. Pathshala recently entered its tenth year. Celebrating the school’s anniversary, a three day festival was organised where both the old and the new students presented their works, amidst other festivities.

Pathshala’s certificate awarding ceremony ? D. M. Shibly

Pathshala’s certificate awarding ceremony ? D. M. Shibly

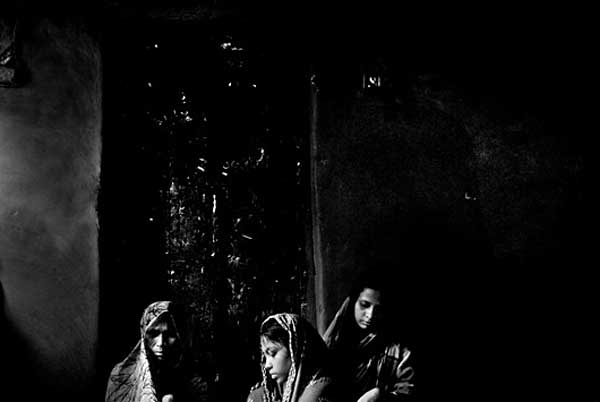

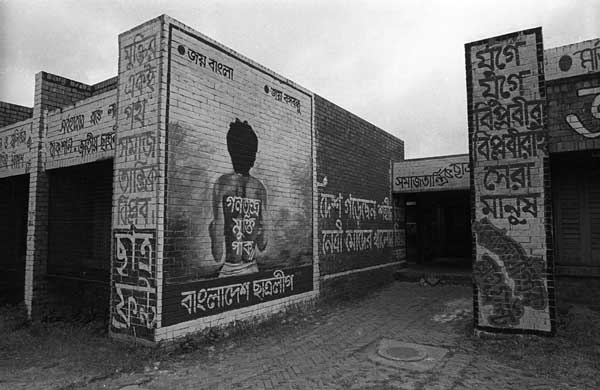

A photography exhibition titled ?Studying Life? began marked the beginning of the festival on February 1 at the Drik Gallery. Exhibiting works by some of the most celebrated students of the school, this event was inaugurated by Atiqul Huque Chowdhury and Dr. Shahidul Alam. The exhibition, which will continue up to February 15, features thirty six photographers, including Munem Wasif, Abir Abdullah, GMB Akash, Tanvir Ahmed and many more. On February 2, certificates were distributed to the students who had finished their respective courses, starting from the basic to the undergraduate level. ?We had a full-fledged festival, complete with a winter Pitha Utshob,? says Joseph Rozario, the Administrative Manager of Pathshala. ?Students, teachers, along with a few photographers from outside the country had discussions on photography. These photographers also presented some of their unique works. The day ended with a film made by one of our own students,? he says.

Celebrating a decade with fireworks ?D. M. Shibly

Celebrating a decade with fireworks ?D. M. Shibly

The last day of the festival, February 3, was an ?absolute blast,? according to Din M Shibly, a Pathshala graduate who now teaches at the school and works for the monthly magazine Ice Today. The highlight of the day was when Prachyanat, the musical theatre group, performed at the school, much to the delight of the students and also a number of guests who had turned up at the celebrations. The notion that photography cannot be a proper career no longer holds true. Many students from Pathshala are working in the media, both local and international. Tanveer Ahmed, student of Pathshala who now works at Drik News, recently had one of his photographs published in the Time magazine as the picture of the year. The photograph shows a grandfather carrying the dead body of his grandchild after being hit by the Sidr cyclone last year. Many other Pathshala students have won international awards. Alam says that young people believe that there is more glamour and less money in this profession. ?It is actually the other way around,? he explains. He plans to work more on visual literacy, hold workshops in schools and develop this field as an academic subject in the educational institutions in Bangladesh. Photography is much more than capturing a mere image. It is what one captures within the image; emotions, environment, thoughts, social perceptions and so on. One simply has to look into a photograph to discover these elements, rather than looking at it. As actor and author Sir Dirk Bogarde had put, ?The camera can photograph thought.?

Category: Drik and its initiatives

Studying Life

![]()

![]()

10th year of Pathshala

Video on Pathshala by Brian Palmer. Commissioned by Pullitzer Foundation:

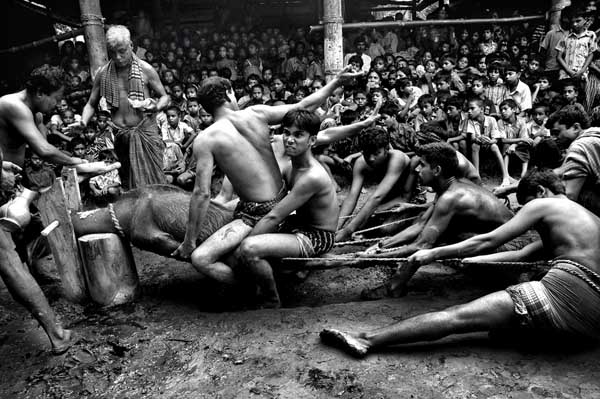

Boli. Goat being sacrificed at Hindu religious ceremony. ? Saikat Mojumder.

Boli. Goat being sacrificed at Hindu religious ceremony. ? Saikat Mojumder.

Rashid Talukder had been unwell and had excused himself. The other board members Afzal Chowdhury, Mahfuz Anam, Nawazesh Ahmed and I had pored over the crude portfolios. Much of the work was raw, but there was freshness and a vibrancy that touched us all. This new school would take risks. Ideas would be given a chance.

The students have emulated that principal characteristic of Pathshala. Reaching for the impossible has become the norm. Pushing the school and themselves to the limit has been their mode of practice. Dreaming, a way of life.

On the day of the first workshop, with World Press Photo in 1998, a hastily flung white cloth had covered up the bricks being used for the unfinished construction of the computer lab. On its tenth year, the school boasts achievements by students that is the envy of schools worldwide. The early partnerships, with World Press Photo Foundation, The British Council, Panos Institute, The Thomson Foundation and Free Voice (formerly CAF) have all played an important role, but the new liaisons, with the University of Liberal Arts in Bangladesh, and the upcoming regional masters programme between universities in Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, Nepal, Norway and Pakistan are paving the way for a school that has matured beyond its years.

The academic exchanges with Oslo University College in Norway and Edith Cowan University in Australia provide Pathshala students an opportunity to share experiences with students of very different backgrounds. The long-term partnerships with Sunderland University, Bolton University and the Danish School of Journalism, offer educational opportunities for students with other world class institutions. The internship opportunities at Drik, Chobi Mela and Drik News offer on-the-job training that is invaluable in professional life. The regular participation in international festivals and workshops provide a world-view essential to becoming established in the global marketplace. And then there is the acid test. Emerging students are in demand, and ever since Pathshala started, all students who have graduated are gainfully employed. Some are already at the very top of their profession.

But the goal of Pathshala is far more than teaching photography. It is about using the language of images to bring about social change. It is about nurturing minds and encouraging critical thinking. It is about responsible citizenship. In a land where textual literacy is low, it is about reaching out where words have failed. In a society where sleek advertising images construct our sense of values, studying at Pathshala is about challenging cultures of dominance.

Curating an exhibition of so diverse a group is always difficult. One wants to be inclusive but selective. Demonstrate trends, but value differences. Nurture new talent, but recognise excellence. Choose favorites but not be partisan. The greater importance given to some artists has as much to do with what needs to be said now as it has to do with the calibre of their work. Pathshala cannot be an academic island untouched by local realities. While recognising the merit of those producing quality work, space has also to be given to voices that need to be heard now. These are images of ‘Now’ being articulated.

Shahidul Alam

A True Pathshala

The word Pathshala, a traditional Sanskrit word for a seat of learning, was generally associated with the shade of mango trees in open fields. There were no walls, no classrooms, no formal structures, but children gathered to listen to wise folk. It was wisdom being shared.

Having decided that the language of images was the tool to use to challenge western hegemony and to address social inequality within the country, Drik had begun to put in place the building blocks to make it happen. The agency was serving people already in the trade, but opportunities for learning had to be created. There wasn?t a single credible organization for higher education in photography in the region. One had to be built. Taking advantage of a World Press Photo seminar on 18th December 1998, the school was setup. A single classroom was all that was available. The visiting tutors Chris Boot (formerly with Magnum, then with Phaidon) and Reza Deghati (National Geographic) conducted the workshops. I continued as a lone tutor. Kirsten Claire an English photographer whom a friend had recommended, came over soon afterwards and stayed for a year. We paid her a local salary, the best we could afford. The two of us formed the faculty.

A stream of tutors, all friends willing to be arm twisted, came at regular intervals. For some we provided air fare and modest accommodation. Some came at their own cost. Some slept on our floor. Some, like Ian Berry, who had come over on an assignment, were simply roped in. The students, most new to the craft, didn?t know they were rubbing shoulders with the greatest names in photography. And it was an impressive list of names. Abbas, David Wells, Daniel Meadows, John Vink, Ian Berry, Ingrid Pollard, Martin Parr, Morten Krogvold, Pablo Bartholomew, Pedro Meyer, Raghu Rai, Reza Deghati, Robert Pledge, Steven Mayes, Tim Hetherington, Trent Parke and many others had spent quality time with Bangladeshi photographers. Some had come even before Pathshala started. Some, like Robert Pledge, Reza Deghati, Abbas, David Wells, Morten Krogvold and Raghu Rai, were repeat visitors. Few demanded payment; none flaunted their superstar stautus, one even made an anonymous donation. They all wanted to be part of a very exciting journey. One or two wanted to be on the faculty to embellish their CVs, but they all gave generously, and this organization has been built on their labour of love.

Lazy at first and unaware of how special the environment was, the students soon became infected by the passion of their marvelous tutors. They studied photography, economics, statistics, environmental studies, visual anthropology. They were in a true Pathshala, studying life. And it showed. Despite the limited resources of the school, we maintained one goal we had set for ourselves at the outset. Every emerging student was gainfully employed. The trend has continued since 1998. They got selected for the prestigious Joop Schwart Masterclass. They won awards like the Mother Jones, World Press, the National Geographic All Roads and a host of other prestigious awards. Time Magazine, Newsweek, New York Times and other leading publications began to hire them, and the reputation spread. Soon students and interns from other countries began to come in. Most were from neighbouring countries, but some from far flung places like Norway, the USA and Australia wanted to join.

The number of regular tutors has grown from the original two to eleven. Eight are former students. The tutor to student ratio remains very high. DrikNews, a news agency which gives emphasis to rural reporting, hires former Pathshala students for its their core staff. The staff photographers and picture editors of most major newspapers in Bangladesh are from Pathshala. Some are also working in television stations and other broadcast media. And Pathshala continues to defy gravity. A school of photography in one of the most economically impoverished nations and with no external support, continues to produce some of the finest emerging photographers.

Shahidul Alam

The school of photography Pathshala, is entering its tenth year. Greetings to all students, teachers and well-wishers who have journeyed with us over the last nine years. An exhibition “Studying Life” featuring the work of Pathshala students and alumni will mark the beginning of our celebrations.

Pioneer playright and theatre person Atiqul Huque Chowdhury will inaugurate the exhibition on 1st February 2008 at 5:00 pm at Drik Gallery.

The exhibition will continue till 15th February 2008 and will be open to all from 3:00 pm till 8:00 pm.

You are invited.

Inauguration date: 1 February 2008

Time: 5:00 pm

Exhibition duration: 1 February – 15 February 2008 (3-8 pm. every day)

Venue: Drik Gallery, House 58, Road 15A (new), Dhanmondi Residential Area, Dhaka.

Programme:

1 February 2008

5:00 pm, Drik Gallery

Opening of photography exhibition “Studying Life”

2 February 2008

Pathshala Campus (16 Sukrabad, Panthapath)

3:00 pm: Certificate Distribution

3:45 pm: Discussion on Photography

4:30 pm: Portfolio Presentation

5:15 pm: Film Show

3 February 2008

Pathshala Campus (16 Sukrabad, Panthapath)

2:30 pm: Portfolio Presentation

6:30 pm: Songs by Prachyanat

8:30 pm: Dinner

Selected photographs from the exhibition can be seen in the Drik 2008 Calendar:

Submissions are invited for Chobi Mela V. The theme is “Freedom”. The online submission form will be available at www.chobimela.org from the 7th February 2008.

Bangladesh Now

![]()

The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) were setup as a crack team to support law enforcement. Numerous accusations of extra judicial killings have been attributed to RAB, usually followed by a government press release about people having died in a ‘crossfire’. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

Dark glasses, black bandana, arrogance in his face. ‘The Protector’ strides with purpose. A new word enters our lexicon. You can now ‘crossfire’ a person. No questions asked.

Hanif, a mill worker, was shot dead by the police during a protest rally organised by the workers. Two hundred workers were injured. Crescent jute mill, Khalishpur, Khulna, 11 September 2006. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

She mourns in silence. Her man, a worker in a mill, is no more. His crime? Demanding payment for his labour.

Workers protest on the streets of Khalishpur, even during emergency. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

A child screams.

Soon after coming to power, the caretaker government ordered all illegal constructions and slums be torn down. Those affected do not know where to find shelter since laws and their interpretations are mostly anti-poor. Dhaka Bangladesh. 24 January 2007. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

Evicted from a slum that offered little, his parents in search for even less.

Muslim and Adivasi women unite in their fight against multinationals. Phulbari Bangladesh. 30 September 2006. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

These green fields will disappear if coal mining starts. Phulbari Bangladesh. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

Angry women protest the illegal hand-over of their land to multinationals.

————————————-

Choles Ritchil killed in custody

————————————-

And the missing photograph. The one we cannot show. The one of the Adivashi leader tortured and killed in custody. He too had the temerity to resist government takeover of his ancestral land.

A member of Rapid Action Battalion (RAB, Bangladesh’s elite security force), checks the grounds with a dog squad to ensure security of the 14 party led Awami League’s grand rally the next day. Paltan, Dhaka Bangladesh. December 17 2006.

? Munir uz Zaman/DrikNews

Ratan Kumar, suspected of stealing a gold necklace, was tortured at Bogra Police Station. This photograph (taken with a mobile phone) was published in a daily newspaper, resulted in police officials seen in the picture (the officer-in-charge, three sub-inspectors and a constable) being suspended from active duty. Bogra Bangladesh. 28 January 2007. ? DrikNews

Police fired tear gas shells and rubber bullets to stop agitated students at Dhaka University campus. As protests engulfed the nation, curfew was declared in 6 divisional cities from 8 at night. A student hurls back a tear gas shell. Dhaka Bangladesh. 22 August 2007.? Azizur Rahim Peu/DrikNews

Now is a difficult time. A time for reflection, a time for retrospection, a time for defiance. Sadly for most Bangladeshis, now has always been difficult. Apart from the brief euphoria after independence in ’71, there were the lesser joys when the autocrat left in ’90, on winning a Nobel peace prize in ’06 and even temporary relief when emergency was declared in January ’07. But those feelings have been short-lived. Particularly for the poor. When elephants clash it is the grass that gets hurt.

Soldiers and rescue workers recover a child’s body from landslides caused by heavy rains on the deforested hills of Chittagong city. One hundred and six people died, many more were injured. Chittagong Bangladesh. 12 June 2007. ? Tanvir Ahmed/DrikNews

A woman mourns the death of her family members, all of whom died as a result of the mudslide. Chittagong Bangladesh. 12 June 2007. ? Tanvir Ahmed/DrikNews

Life is fearful for a slum-dweller. When will she face the next eviction? Dhaka Bangladesh ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

Arrests in the night, the brutality of high prices and the daily grind of poverty are the realities that wear people down. But they are warriors. Despite the weight of unjust governance, despite the price they always end up paying, they still protest. And the photojournalists? When justice is compromised. When the poor are trampled under the march of ‘reform’. When fear evokes silence. When familiar faces turn away. To stay ‘neutral’ is to stay aloof. They stand on the side of the oppressed. Unashamedly so.

Rickshaws without proper licenses seized by police and dumped near Police Control room. Rickshaws are environment-friendly and affordable by the middle class and often the only source of paid work for men migrating from villages in search of work. 17 February 2007. Dhaka Bangladesh. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

A village woman dries dhan (husked rice grain) as flood waters recede. Chilmari, Rangpur. August 8 2007. A village woman dries dhan (husked rice grain) as flood waters recede. Chilmari, Rangpur. August 8 2007. ? Munem Wasif/DrikNews

On Tuesday the 4th of September 2007 DrikNews will hold its inaugural photographic exhibition “Bangladesh Now”. The photographs shown are a selection from the exhibition.

The exhibition will be opened by Nurul Kabir, editor, New Age, who will share his views about the current situation in Bangladesh,

before the opening. The program starts at 5.00 pm.

Drik will be 18 years old on that day. We’d like you to be with us

Portraits of Commitment

Portraits of commitment

Why people become leaders in the AIDS response

Challenges help us find our true selves. They take us on a journey within the depths of who we are, leaving us at a destination we hope is worthy. Some people find themselves at lesser places.

AIDS is one of those challenges.

The South Asians in this book tell how AIDS has made them a better doctor, researcher, legislator, citizen or person. We know AIDS affects our daily life?but because of it we now have more respect for human rights and individual choice where once there was little or none. AIDS has helped us to see who we want to be.

Photographs by Shahidul Alam. Interviews by Karen Emmons. Commissioned by UNAIDS.

Viewers watching “Portaits of Commitment” at Fort Station in Colombo on the 21st August 2007, as part of ICAAP8. ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

A story from Sri Lanka on WAD: Positive & Strong Princey Mangalika on HIV/AIDS

Reviews: IPS. Daily Mirror

Shilpa Shetty. Actress, Big Brother Winner. Mumbai India. “Being a celebrity has advantages – people hear you. I thought I should make use of this position and speak out.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Tahir Baig Barlas. Corporate Manager. Karachi Pakistan. “We have the opportunity to do something now before it’s too late. Let’s not be reactive.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Sabina “Putul” Yeasmin, Daughter of a sex worker. Tangail Bangladesh. “I gave wrong information to make others afraid, as I had been. I had to go back and give correct information.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Sapana Pradham-Malla. Advocate. Kathmandu Nepal. “I can’t turn away.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Sally Hulugalle. Community Worker. Colombo Sri Lanka. “I want a better deal for those who are voiceless.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Rev. Alex Vadakumthala. Priest. New Delhi India. “The church finds its meaning when it responds to the challenges of the times.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Rajiv Kafle. Former Drug User. Kathmandu Nepal. “I saw a need and an opportunity where I could step up and really make a difference.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Noor jehan Penazai. Partliamentarian. Islamabad Pakistan. “These politicians have to realise it’s a very serious disease and we have to talk about it.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Dr. Ananda Wijewickrama. Doctor. Colombo Sri Lanka. “I had to do something for the patients …they needed a place to go, to be consoled and, if dying, to die with dignity.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Arif Jafar and Anis Fatima, MSM and mother. Lucknow India. “I am grateful to Allah he gave such a son to me.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

Habiba Akter. Dhaka Bangladesh. Positive Counsellor.

“I have no choice. If I don’t do it no one will.” ? Shahidul Alam/Drik/MajorityWorld

An exhibition supporting the book opens at the Barefoot Gallery, in Colombo at 7:00 pm on the 18th August. 704 Galle Rd. Colombo 3.

The South Takes The Picture

![]()

New Internationalist editor Dinyar Godrej?s email asking us to participate in the 400th issue of the magazine a few months ago was a great opportunity. But with Dhaka in flames and our own struggles to ensure some semblance of fairness in the elections, we passed it on to other activists.

Vanessa Baird?s subsequent email suggesting an issue of the New Internationalist based on our organization ? the Drik photo agency and Pathshala photography school ? as an example of how some of us in the Majority World are challenging the global information flow, came as an unexpected reprieve.

Our immediate political problems in Bangladesh hadn?t gone away. A tribal activist had been brutally killed by the army, and a journalist friend who had been courageously reporting on military misrule had been picked up in the middle of the night.

So things were far from easy on the home front, but writing about, and showing, what had been our central struggle over the last 20 years was an opportunity we couldn?t miss. We had all lived it. More importantly, with our majorityworld.com site up and running and slowly beginning to get pictures into print, we weren?t just talking about change. We were witnessing it taking place.

This issue of the magazine could hardly have been better timed. Majority World photographers embraced the idea: from the small studio of VAST ? a voluntary artists association in Bhutan ? to a crammed office room in Santa Cruz, Bolivia; from the enthusiastic Photo Circle in Kathmandu to a hotel lobby in Dili, Timor Leste.

Our FTP site has been busy and the pictures ? some of which are featured in the pages of this issue ? have been flowing in. After years of trying to persuade others, Majority World photographers have taken things into their own hands. Watch this space.

Shahidul Alam, Drik/Pathshala for the New Internationalist Co-operative

—————————————————————————————-

The above editorial had been written several weeks ago, but the magazine has just hit the stands. Links to the PDFs of the magazine follow. The online version should be up on the NI site in about six weeks.

26th July 2007. Manila.

ni403cover.pdf

01.pdf

new-internationalist-majority-world.pdf

Taking care of the caretaker

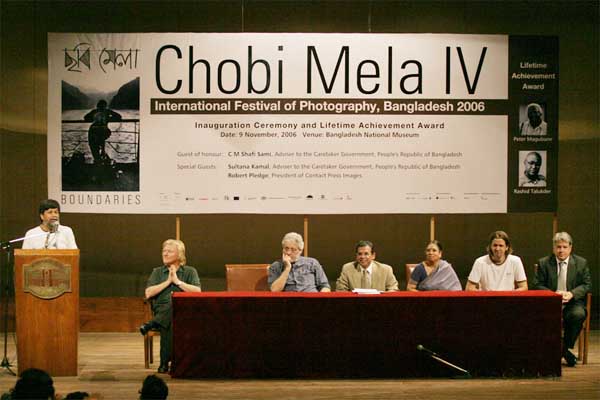

It was a dramatic ending to Robert Pledge?s presentation. Via Topu and Omi, I?d received the news that the military had been called out. Robert wanted to finish the presentation, but once I?d announced the government?s decision, the auditorium of the Goethe Institut quickly emptied out. This particular Chobi Mela IV presentation had come to an abrupt end. It was 1987 revisited.

Noor Hossain had painted on his back ?Let Democracy be Freed? and the police had gunned him down on the 10th November 1987. But the people had taken to the streets and while we were scared the military would come out, there was no stopping us. It had taken three more years of street protests, before the general was forced to step down. The people had won. But then it had been a military general who was ruling the country. This was a civilian caretaker government. The general mistrust of a party in power, had resulted in this unique process in Bangladesh where an interim neutral caretaker government headed by a Chief Adviser (generally the most recently retired Chief Justice) and consisting of other neutral but respected members of the public were entrusted with conducting the elections. Why then the military? Yes, the president was a Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP, the largest party in the outgoing coalition government) appointee, there are ten advisors who are meant to be neutral.

A free and fair election hasn?t yielded the electoral democracy we had hoped for. After each term, the people have voted out the party in power, only to be rebuffed by a political system that has never had the interest of the people on their agenda. Still, the elections were held, and despite the fact that there had been one rigged election in 1996 (rejected and held again under a neutral caretaker government), an electoral process of democratisation, was slowly developing.

This time however, the total disregard for the electoral process has created a sham, and the three key people in this electoral process, the president, the chief adviser, and the chief election commissioner (CEC), are colluding against the people. The first two, being represented by the same person, was a BNP appointee. He also happens to be the head of the military. The CEC, now a cartoon character, had also been appointed by the BNP while it was in power. Coupled with a clearly flawed voters list, this has removed any hope of a free and fair election. Can the caretaker government genuinely conduct a fair election? I believe it still can, if given the chance, despite the president?s lack of credibility. But for that to happen, the military, the bureaucracy and the police need to remember that it is with the people that their allegiance lies.

However, it does depend upon the removal of the other obstacles. The election commissioner cannot constitutionally be removed, and his removal is central to the opposition demands. What then can we do? There is only one body higher than the constitution, the people themselves. The advisors need to be empowered if they are to pull off this election. Sandwiched between a partisan executive head and another partisan CEC, the advisers risk becoming irrelevant. The only way this can be checked is if people come out in droves. Not ?hired for the day? supporters but ordinary people committed to civilian rule, and a multi-party system.

It is we the people who need to take to the streets. And it is time we sent out the message to all political parties, that an entire nation cannot be appropriated. They need to be told that we did not liberate our country in vain, and despite the poverty and the hardship that we go through, we will not be cowed down, and will not blindly tow a party line, when the party itself has disengaged from the people. If tomorrow, every woman man and child takes to the street of Bangladesh, there is no power, not the military, not the president, not the advisers, not the CEC, not the BNP and not AL that can stop us.

There is hope yet. The advisers have had the good sense to reverse the home ministry?s unilateral decision to call out the army and the president and chief adviser has been challenged for taking such a step. Whether the advisers can continue to take such bold steps depends on our ability to bolster their nebulous position.

Blockades and hartals do hurt the economy, and ironically, it is the person in the street who is the most vulnerable. But faced with an attempt to take away the only chance she has to exercise her right to elect the government of her choice, she has little option left but to take to the streets. As the world is finding out, in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and wherever else there is conflict, a military victory is never a victory. If the anger of the people is to be quelled, then the underlying causes of discontent need to be solved. Flexing the muscles of the military, will only put a lid on the boiling pot, and the longer the lid is pressed down, the bigger will be the eventual explosion. More have died today, and with every death, the flashpoint looms closer.

Chobi Mela IV has continued despite it all. The dancing in the all night boat party,

the heated arguments at every meeting point, the mobile exhibitions, all went on despite the turmoil. The presentations on the night of the 11th, with Yumi Goto, showing work by the children from Bandar Aceh, Neo Ntsoma showing her work on youth culture in South Africa, Chris Rainier showing his long term projects on ?Ancient Marks?, and the deeply personal, but very different accounts of Trent Parke

and Pablo Bartholomew, made one of the most intriguing evenings I can remember. The packed audience that had braved the blockade had perhaps an inkling of what was to come. Morten had a full house for his ?gallery walk? at the Alliance Francaise and Trent?s workshops were packed out. The grand opening was at the National Museum, where we had one fifth of the cabinet opening the show. Kollol gave a passionate rendering of his song ?Boundaries? written especially for the festival. The rickshaw vans designed to take the festival to the public, plied the streets of Old Dhaka, Mirpur and other areas not used to gallery crowds.

The chief guest, adviser C.M. Shafi Sami, the special guests adviser Sultana Kamal and Robert Pledge, photographers Morten Krogvold and Trent Parke and the scholarship recepient Dolly Akhter all spoke eloquently. Little did the audience know about the drama that had taken place the night before. With the museum functionaries doing their best to keep us from putting up the Contact Press Images show (http://www.chobimela.org/contact_press_images.php), we were under pressure, but working all through the night and sleeping on the museum floor, we managed to put the show up on time.

Last night, the empty streets, looked ominous as I dropped off Chulie, Robert and Yang, and people have been dying in the streets.

Since then we have had Morten Krogvold?s passionate presentation at the gallery walk at Alliance, Rupert Grey?s clinical dissection of the law and his dry British humour,

both at the British Council and the Goethe Institut, Saiful Huq Omi?s disturbing but powerful images of political violence, Cristobal Trejo?s poetic rendering of an unseen world, Richard Atrero De Guzman?s honest response to difficult questions about representation and my own presentation on natural disasters and their social impact have all been well attended, despite the tension in the desolate Dhaka streets. The evening presentations close tonight with an insightful film by Indian film maker Joshy Joseph, presentations by Norman Leslie and a behind the scenes look by the photographers at the Drik Photo Department, Md. Main Uddin, Shehab Uddin and Amin, Chandan Robert Rebeiro, Imtiaz Mahabub Mumit and Shumon of Pathshala and Mexican exhibitor Cristobal Trejo. The shows go on as they always do at Drik.

In 1991, a woman with her vote had avenged Noor Hossain’s death.

A fortnight ago, the city was in flames, and a stubborn chief election commissioner is stoking the flames again. It is a fire he and his allies will be powerless to stop.

Shahidul Alam

Dhaka

Chobi Mela site

Blog by Australian curator Bec Dean

Short video on Chobi Mela IV

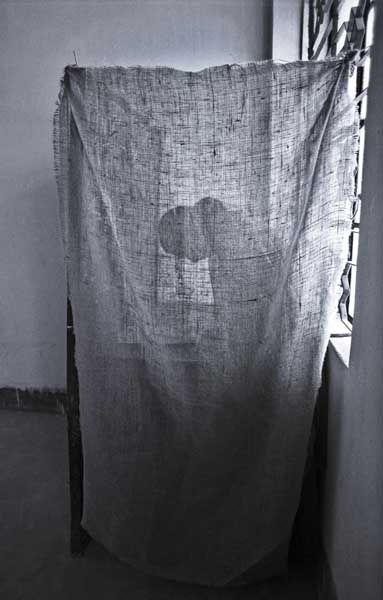

Boundaries

Chobi Mela IV

She packed her load of firewood onto the crowded train in Pangsha. The morning sun peered through the lazy winter haze. The vendors called ?chai garam, boildeem? and the train slowly chugged out of the station, people still clambering on board, or finishing last minute transactions. Some saying farewell. The scene had probably not been very different a hundred years ago. Maybe then, they carried pan in place of firewood, or some other commodity that people at the other end needed. She would come back the same day, bringing back what was needed here. Only today she was a smuggler. The artificial and somewhat random lines drawn by a British lawyer had made her an outlaw. She was crossing boundaries. There were other boundaries to cross. The job a woman was allowed to do, the class signs on the coaches that she could not read but was constantly made aware of. The changing light and the smells as sheet (winter) went into boshonto (spring). The Ashar clouds that the photographers waited for, which seemed to wait until the light was right.

Rickshaw wallas find circuitous routes to take passengers across the VIP road. Their tenuous existence made more difficult by the fact that permits are difficult to get, and the bribes now higher. Hip hop music in trendy discos in Gulshan and Banani with unwritten but clearly defined dress codes make space for the yuppie elite of Dhaka. The Baul Mela in Kushtia draws a somewhat different crowd. Ecstasy and Ganja breaks down some barriers while music creates the bonding. Lalon talks of other boundaries, of body and soul, the bird and the cage.

Photography creates its own compartments. The photojournalist, the fine artist, the well paid celebrity, the bohemian dreamer, the purist, the pragmatist, the classical, the hypermodern, the uncropped image, the setup shot, the Gettys and the Driks. The majority world. The South. The North. The West. The developing world. Red filters, green filters, high pass filters, layers, masks, feathered edges. No photoshop, yes photoshop. Canonites, Nikonites, Leicaphytes, digital, analogue.

The digital divide. The haves, the have nots. Vegetarians, vegans, carnivores. Heterosexuals, metrosexuals, transsexuals, homosexuals. The straight, the kinky. The visionaries, the mercenaries, the crude the erudite, the pensive the flamboyant. Oil, gas, bombs, immigration officials. WTO, subsidies, sperm banks, kings, tyrants, presidents, prime ministers, revolutionaries, terrorists, anarchists, activists, pacifists, the weak, the meek, the strong, the bully. The good the evil. The hawks the doves. The evolutionists, the creationists. The crusaders the Jihadis. The raised fist, the clasped palms. The defiant, the oppressive, the green, the red. The virgin.

Whether cattle are well fed, or children go hungry, whether bombs are valid for defence, or tools of aggression, boundaries ? seen and unseen ? define our modes of conduct, our freedoms, our values, our very ability to recognise the presence of the boundaries that bind us.

Festival Website

Doing What I Do

Why do I do what I do? I know how I started, partly by accident, when I got stranded with a camera I had bought for a friend, but that in itself cannot explain the joy, the passion, the amazing high that I get when I see something magical in my frame. So I’m a photojournalist. Like so many others who started off in this noble profession, I too believed I was going to change the world through my images. It took a while for reality to settle in. A while to know, that taking good pictures wasn’t enough. There were gatekeepers who decided which pictures would get used, and how they might be used, and the gatekeepers generally didn’t share my ideology or passion.

It was children who shaped my visual world. Initially, as a photographer in London, I would go round asking adults with children, if I could take portraits of their kids. Some would agree, and I would go over to their homes, put down my synthetic sheepskin rug, get the kids to smile at my camera and take happy pictures. If things went well, they would buy some pictures, and we would all be happy. Not the ultimate in photography, but it paid the bills, and helped me save some money that I thought would allow me to start afresh back home.

In Bangladesh, the children had been swapped for a new range of subjects. Ice cream and plastic toys, the odd glamour shot, some celebrity. Ceramics and fancy machines. I photographed the lot. It was as an activist, in our attempt to remove an autocratic leader, that my camera finally knew what it wanted. With the adrenaline flowing as we marched through the teargas, my camera learned to love the smell of the streets. We braved the curfew, to photograph the courage of a people and the tyranny of a tyrant. I never got a picture published in those days, as a democracy movement in the majority world, was simply not news. A flood or a cyclone was much more interesting. But when we eventually forced the dictator to step down, I photographed the rejoicing, and later at our long awaited election, I photographed a woman casting a vote. When we put up the images for an impromptu exhibition, over 400,000 people came to our three day show.

But international media wasn’t interested, and it wasn’t till the cyclone in 1991, that they started asking for images again. The same western photographers came over at the first smell of disaster, and went back with the same helpless images, reducing a proud people to icons of poverty. Even locally, the images we produced and the words we wrote, seemed to have little effect. This powerful tool that I thought I’d picked up, suddenly felt blunt in the face of corruption and indifference.

That was when, while talking to a group of working class children I was training, I was shaken. Sitting on the school verandah, 10 year old Moli, looked at the photograph of the bodies of children being dragged. ?O that was the fire in number 10? she said.

“How do you know?”

“Everyone knows.”

“What happened?”

“Nothing ever happens.”

Then she waits a bit, and says, “If I had a camera, I’d take his picture and put that guy in jail.”

It was the conviction of that 10 year old girl, that fired me up again. I remembered a moment six years ago, during a flood, where children who had taken shelter in a warehouse, insisted that I take a picture of them. As they stood by the large open window, all proud and standing at attention, I noticed that the boy in the centre was blind. He stood with his chest out, pushing back the other kids. Staring straight out at the camera he couldn’t see for the photograph he would never know. I began to realise how much more important the photograph was than simply my weapon for change. It represented hope and belief and could give a sense of dignity to many.

My photography slowly changed, as did the world around me. I began to see things that had never existed before. People mattered in a way that they hadn’t mattered before. The man in our neighbourhood, who collected the garbage late at night, pushing his cart in the rain, gathering each scrap of paper that he could sell to keep his family alive, took on a stature of enormous proportions. I wanted my camera to do what Moli and that blind boy had willed it to do. I wanted my camera to befriend the man with the cart. I felt ashamed, I had never stopped to ask his name.

It was at about that time that I met Abdul Malik, on an Aeroflot plane bound for Tripoli. He dreamt of somehow changing his destiny, and I dreamt of somehow documenting his dream. I have never met Abdul Malek since, and I don’t know if came back home and bought the piece of land he hoped to buy, and whether he was able to arrange a marriage for his sister, but I have seen that dream in many eyes. When the very things that the wealthy aspire to, becomes part of a migrant’s dream, the dream becomes illegal. I want my images to challenge that illegality, and all the illegalities that are sprouting around us. The illegality of a right to a homeland, the illegality of protest against oppression. The illegality of wanting a better life. I want to photograph Moli’s dream and that of the blind boy and the man with the cart.

Shahidul Alam

17th August 2003

Everything Smelled of Money

Aid – Bangladesh / WORLD OF MONEY

When you have too much money what else can you do except go to a swimming pool to show off, to say ‘Look at the money I have – I go swimming in a big hotel’s pool.’ The rich and their airs! Coming out with their cars just to show off to us, to the poor, to those of us who don’t have cars. The way they look at us! And their talk: which is better, a white car or a black car? It’s unbelievable, the arrogance!

Advert We are poor. But the fact that we have cameras and know how to take photos makes people uncomfortable. And so something simple becomes complicated. People who see us keep asking us ‘Accha, are these the cameras you use?’ But, you see, the camera’s not the point. The point is to take photographs. It doesn’t sit well with a lot of folks that the children of the poor should have cameras. Makes you laugh. Once Bhai’ya took some of our shots to the Lab for printing. The people at the Lab thought that one of the photos was his. ‘Take a look at Shahidul Alam’s work,’ they said. Well, it was actually taken by Iqbal, and when Bhai’ya told them so, they just shut up and wouldn’t say anything more.

Hamida and Rabeya have been abroad. The word has spread. That’s how they are introduced, as having gone abroad. We take photos. That is not our identity however. The point is who has gone abroad. Yet another way to show off is English. You aren’t anybody if you don’t know English. As if the real thing, the only thing, is not the work itself, but whether you know English. It’s such a fashion to speak it. They say you have to know it, but what do the foreigners know? Shouldn’t all those photographers and all the other visitors who come here know Bangla? Nobody tells them ‘You should know Bangla’. Through our photographs we want to change things. But lately the going has been tough. With the children of the wealthy it is enough that they take photos, but with us it seems that we have to prove ourselves by learning English too. What will happen to those English-speaking friends who also carry on the struggle? Will they learn our language and join us? Oh come on! Will they not join ranks with us? What then is our language of photography to be? These comments were made during an informal discussion involving |

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them.

We remember the time we had to go to some UNICEF meeting or other with Bhai’ya (Shahidul Alam). It was in the Sonargaon Hotel. A huge, fancy affair, where we had trouble walking, where our feet kept slipping on the shiny lobby floor. A different world, the world of the rich. As if that wasn’t enough, Pintu had lost one of his sandals on the way there. We knew we wouldn’t be allowed inside in bare feet, but Bhai’ya told us that there was no need to worry, that everything would be fine. So we walked on that slippery floor and looked everywhere. Everything seemed so grand, everything smelled of money. People throw away so much money! In the middle of the hotel was a swimming pool with almost-naked foreigners in it. We felt too ashamed to look at them. When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’

When we go somewhere people usually comment ‘Oh you poor deprived children’. Nonsense! If they grab all the opportunities of course we’ll be deprived. First they take everything for themselves, then they coo ‘Oh, you poor deprived child’. If we are not given a chance, how can we make it? Our speech, the way we talk is offensive to the bhadrolok, the upper class. ‘Oooh, your pronunciation,’ they sniff at us, ‘the way your language wanders all over the place.’