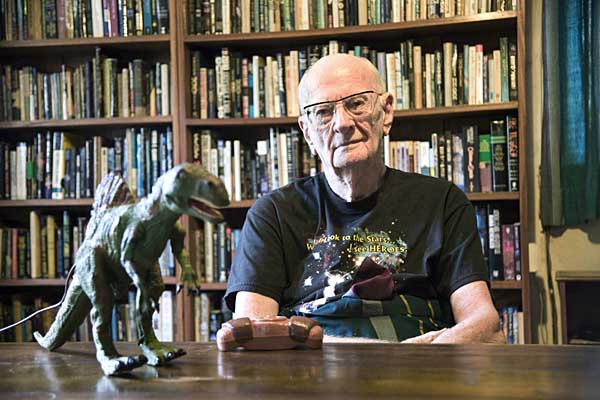

“I’d better put on my sincere smile” he said as he straightened up realising I was about to take his picture. Arthur C Clarke, the king of Sci Fi, was only half joking. The sincere smile is certainly not the monopoly of the pre-election campaigner. I find myself doing it when I spy a camera. Or put on a more sombre expression depending upon what seems more appropriate. I straighten my hair. Others turn away, some beam, some get embarrassed. The camera is rarely something one is inert to. Our image something we jealously guard.

The photograph trespasses in other ways. The fine art critic, unsure of how to value the medium, is uncomfortable in photographyland. Flirting with reality, rejecting the norms of classical art practice, the deliberately banal, the quietly provocative, the inanely repetitive and even the stunningly picturesque photograph, unsettles viewers on gallery walls. Is it good? Should I like it? Should I pay?

Media gatekeepers not versed in the language of pictures make cliche’d statements weighing images in word terms. They recognise its value but are reluctant to make way for those visually more literate. A caste system where the photographer is at the lowest rung, allows word people to pull rank, even when clearly out of their depth.

So what is it about the photograph that makes it so problematic? Its association with veracity gives it a power other art forms or cultural practices lack. But surely one can willingly embrace a powerful medium.

Is b/w better than colour? Is analogue superior to digital? Can a medium dependent on technology be considered real art? These meaningless questions have not yet been put to rest in mainstream discourse and they get in the way of appreciating a photograph. We are all photographers in a way in which we are not all painters or singers or dancers. As such, the reading of a photograph should have been easy. Indeed the undeniably strong engagement of the photograph with the viewer demonstrates that it is easy to ?read? a photograph at an emotional and spontaneous level. Why then should the analysis of a photograph not be so facile?

The inability to categorise the photographic image, makes it difficult for us to pin it down in terms we are comfortable with. It was easier when technique was so vital to the production. We could understand the rich tonality of an Ansel Adams, the seductive form of a Weston pepper, the fluid luminosity of a Sally Mann, the complexity of a Gilles Peress tableau or the vibrant lines in a Raghu Rai image. We could appreciate the mastery of the craftsperson. Admire the eye. It is not merely the Cindy Sherman movie-still or the matter-of-factness of the German contemporary school that challenges this representation, but also the snapshot and the family album that vies for attention and finds itself on museum walls.

The traditional genres that codified photography are no longer so distinct. Curators play with this ambiguity providing new insights into photographic practice that has long resisted such analysis, but there are hidden dangers to this process. It has led to concerned photography being considered passé. In the hallowed world of limited-edition copies, the fine art print is about the object and not its purpose. Form triumphs over content.

The amateur grabs of Abu Ghraib or killing of civilians, cleansed of blood and sanitised by theory, have also become fodder for the art connoisseur and the artification of photography has led to the de-politicisation of content.

Photography must go beyond the celebration of technique. The posturing of experts must not become a substitute for critical thinking. In attempting to make photography halal to the art world and in the rarified air of multimillion dollar price tags, the social and political significance of photography is something we risk losing. Photography has repeatedly helped change the course of history in its 170 years of existence. The forced closure of recent photography shows in Bangladesh, such as ‘Into Exile: Tibet 1949 to 2009’ and ‘Crossfire’ are evidence of its continued power. It is photography’s trespass that will ensure that art has relevance not only to collectors but also to the person in the street.

Asalaamu Alaikum,

Sir,

I am very small photographer of Srinagar,kashmir …..