It was a moment that had been etched in her mind. In a workshop with Eugene Richards, one of the greatest photojournalists of our time, Dayanita had been asked, as had all the other workshop participants, to “photograph each other naked”. She was not comfortable with this, and questioned the value of such an exercise. “Trust me,” Eugene had said, “I want you to realise how vulnerable one can be facing a camera.” It was to be a turning point. Eugene might not have known, but it was this ‘vulnerability’ that Dayanita Singh chose to explore as her medium.

It was as a curator of the show “Positive Lives” an exhibition on people’s responses to HIV/AIDS that I was first introduced to Dayanita’s work. As I looked through the archives at the respected Network Agency, I saw competent photo essays on sex workers in India. The work did not excite me. India, was known for its exoticism, its misery, its otherness. An Indian photographer, documenting the same stories that western photojournalists had established as the face of this great nation, was a disappointment. I could hardly dispute the images. She was a fine photographer, and while the prints I was shown lacked the quality one might have desired, the photographer was clearly one skilled in her art. That for me, was not the issue. I was later to discover that it was not the issue for this remarkable photographer either.

The images Dayanita produced for Positive Lives were breathtaking. The exquisite composition and her sense of moment were the tactile elements that made her images stunning, but more persuasive was the humanity in her photographs. The tender relationships, the joy, the shared pain, the sense of belonging that she was able to nurture and portray. It was then that the trouble started, a trouble that I am glad I came across. We had meticulously gone through the issues of representing people with HIV/AIDS. They risks people faced due to stigma. The physical dangers the display of the images might lead to. Dayanita’s concern for the people she had photographed meant she had to protect them all the way. It was frustrating for me as a curator. To find pictures which were sublime in their construction, to be left behind, because the photographer felt there was too great a risk of repercussion. Too great a threat, of perhaps things going wrong. We put together a great show, but I knew, photographically it could have been much greater. I also knew we had done the right thing. Dayanita remembered too well, how vulnerable one could be facing a camera.

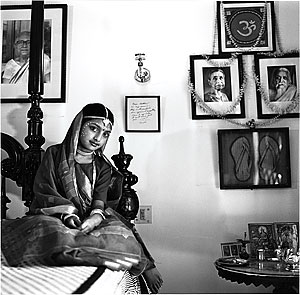

I look back to the stroll through her flat in Delhi, the photographs taken by her mother, juxtaposed with her own. She had been questioning her own work for some time. Questioning her ‘success’ at producing images that regurgitated the “India” the west already knew. She chose to become a mirror to herself, and in that process begin a journey that would create a window to an everyday world. An everydayness that other photographers had shunned. Dayanita and her camera merged into one. She became the fly on the wall, the confidant, the muse. the critic. Before sub-continental literature had made its indelible mark, Dayanita was writing visual novels about middle class India. The glitzy, private, solemn, contradictory, celebratory world of the India today.

She harnessed photography’s unique ability to record detail, its penchant for capturing the fleeting. Its ability to make time stand still. She made the ordinary, special, and the special, ordinary. She also made an important shift within the profession. Recognising that the medium had shifted from the Life Magazine visual spectacles, aware that the spaces for visual journalism had shifted, Dayanita, took on the spaces that other photographers had feared to tread. Her venture into museums and galleries, her indisputable presence as an artist, has challenged the traditionalists in the field of art, who had been unable to grasp the magic of this new medium. Her presence while imposing is also path breaking. A new generation of photographers will wake up to this wider canvas. Some will take it upon themselves to explore this new space. And the ripples will spread. Dayanita meanwhile will continue to nurture the vulnerable. Through the cracks of her mirror she will take us to the other side.

—————————————————-

Indian photographer Dayanita Singh was one of the Prince Claus Fund laureates for 2008. Indian writer Indira Goswami (1942, Guwahati, Assam) was presented this year?s Principal Prince Claus Award of ?100,000 on Wednesday, 3 December 2008, in the Muziekgebouw aan ?t IJ in Amsterdam. Other laureates were, Li Xianting (b. 1949, Jilin Province, China), Venerable Purevbat (b. 1960s, Tov Aimag, Mongolia) , Ousmane Sow (b. 1935, Dakar, Senegal), Elia Suleiman (b. 1960, Nazareth, Palestine) ,James Iroha Uchechukwu (b. 1972, Enugu, Nigeria), Tania Bruguera (b.1968, Havana, Cuba), Ma Ke (b.1971, Changchun, China), Jeanguy Saintus (b. 1964, Port au Prince, Haiti) and Carlos Henr?quez Consalvi (El Salvador, b. 1947 Venezuela). Drik Picture Library has a special relationship with the Prince Claus Fund

Skip to content

Musings by Shahidul Alam

One thought on “Through the cracks of a mirror”